American state legislatures are the progeny of their colonial ancestors. Each colony that became one of the original 13 states had a representative assembly that, with minimal changes, was transformed into a state legislature following independence. In turn, those first state legislatures became models for the US Congress and all subsequent state legislatures.

THE COLONIAL ASSEMBLIES

It would be easy to assume that the colonial assemblies were all fashioned from the same English mold. Although appealing, such an assumption fails because it does not consider that the assemblies were created at different times, by different people, through different legal mechanisms, and for different reasons. The 1619 Virginia assembly was called because the failing colony’s commercial directors hoped it would boost economic vitality. Assemblies in Connecticut, Maryland, and Massachusetts were rooted in their colonial charters, but colonists had to demand their establishment. Starting in the 1650s, governing boards concluded that assemblies were essential for the development of successful colonies and instituted them. (Note: Unless otherwise cited, the information presented here is drawn from Squire 2012 and 2017a.)

None of the assemblies was created in Parliament’s image. In terms of organization and rules, they were distinct not only from it but also from one another. Indeed, the earliest assemblies had to undergo two transformations to become recognizable legislatures. First, they had to become representative bodies. In Virginia, the initial assembly had two elected representatives from each of the colony’s plantations. In the early New England colonies, however, every freeman met with the governor and his councilors in a “General Court.” However, because the increasing number of freemen made the courts unwieldy decision-making bodies and because it became geographically unrealistic for all freemen to participate in their quarterly sessions, the courts were quickly converted into representative institutions. Subsequent assemblies were established as representative bodies from their start, although Maryland briefly pursued an unusual hybrid model.

The assemblies also had to evolve to become part of bicameral legislatures. Initially, the governor, councilors, and assembly members sat together and made decisions collectively. Bicameral legislatures emerged from these unicameral institutions because councilors were agents of the Crown or proprietors whereas assembly members were agents of the freemen or freeholders. Over time, conflicting viewpoints caused these two groups to literally sit and deliberate apart. Bicameralism became the norm, except in Pennsylvania and Delaware.

American bicameralism differed from the English version in two ways. First, two houses emerged in England to represent different social classes, whereas in the colonies, they were prompted by policy disagreements among groups gaining office through different mechanisms. Second, the House of Lords was a hereditary body and politically independent of both the Crown and the people. In contrast, council members in 10 of the colonies were appointees of the Crown or proprietors and politically dependent on them. And in Connecticut and Rhode Island, councilors were elected by the freemen; in Massachusetts, the assembly selected them.

The assemblies and Parliament differed in other ways as well. Most significantly, a parliamentary system developed in the parent country but not in any of the 13 colonies. The initial rules and procedures used by the assemblies were adapted from those used in Parliament; however, over time, each assembly elaborated on them, making them distinctive. Moreover, some rules appeared first in the colonies. Quorum standards, for example, were instituted for Massachusetts before they were used in Parliament (Squire 2013). Although the assemblies initially relied on ad hoc committees—two were created on the first day of the 1619 Virginia assembly—over time, most established standing committees to handle recurrent matters. During the same period, Parliament discontinued the use of standing committees. Finally, all of the assemblies except in Georgia and South Carolina paid their members whereas during this period, members of Parliament were not compensated.

THE FIRST STATE LEGISLATURES

With independence, the colonial assemblies morphed into state legislatures, but an apparent seamless transition actually was interrupted briefly by the use of provincial congresses (or conventions) in most of the colonies. Provincial congresses were unicameral bodies that fused legislative, executive, and judicial functions during the interregnum between the colonial era and the establishment of sovereign states. When state constitutions were written, however, the legislatures they created resembled their colonial predecessors rather than the provincial congresses.

Provincial congresses were unicameral bodies that fused legislative, executive, and judicial functions during the interregnum between the colonial era and the establishment of sovereign states.

The new states could have opted for new legislative forms; instead, they chose to tweak their colonial institutions. Indeed, Connecticut and Rhode Island made only cosmetic changes to their colonial charters, operating under them well into the nineteenth century. The lack of creativity is understandable because—except in Massachusetts—the new constitutions were written in haste and there was little time for invention.

The new lower houses were the colonial assemblies with new names. They used the same rules and standing committees. The only noticeable change was a sizable increase in the number of seats in most of them. This was done to make the new houses more representative; the added seats covered previously unrepresented areas.

The legislatures in all states except Georgia and Pennsylvania were bicameral. The major structural modification was that all of the upper houses became elected bodies. Calling them a “senate” was Thomas Jefferson’s contribution to the Virginia constitution and it became the national standard. Three bicameral relationships established in the first constitutions have carried through to the present. First, upper houses had fewer members than lower houses. Second, upper-house terms of office were as long as or longer than lower-house terms. Third, upper-house qualifications (e.g., age and residency) were as restrictive as or more restrictive than lower-house qualifications.

The constitutions granted the legislatures several important powers derived from their colonial predecessors. Provisions allowing legislators to select their own leaders appeared in nine constitutions and five constitutions authorized them to devise their own rules. Most of the constitutions gave the lower house exclusive rights to initiate revenue bills.

Minimal attempts were made to delineate powers among the three branches of government. Only the Massachusetts, New York, and South Carolina constitutions gave their governor any type of veto. Instead of creating governments with checks and balances, the first constitutions established legislative supremacy. Legislators could easily dominate governors and judges because, in most states, they had elected them. The era of legislative supremacy, however, did not last long. When the original states replaced their initial constitutions—which most did—and when new states entered the union, the newer documents included provisions that made governors and judges more independent of legislative control (Squire and Hamm 2005, 39–40).

Overall, when surveying fundamental legislative features—that is, the number and names of houses, separation of branches, voting procedures, power to choose leaders and rules, control over taxation, and an executive veto—a clear evolutionary line can be traced from the colonial assemblies to the new state legislatures and then to the Congress under the Constitution. It also is important to appreciate that the first state legislatures were not considered inferior to Congress. Until the 1830s, roughly a third of those who left Congress subsequently served in state legislatures (Squire 2014). The constitutional Congress, however, became another model to emulate; both Georgia and Pennsylvania quickly made their legislatures bicameral to conform to it.

Overall, when surveying fundamental legislative features—that is, the number and names of houses, separation of branches, voting procedures, power to choose leaders and rules, control over taxation, and an executive veto—a clear evolutionary line can be traced from the colonial assemblies to the new state legislatures and then to the Congress under the Constitution.

LATER STATE LEGISLATURES

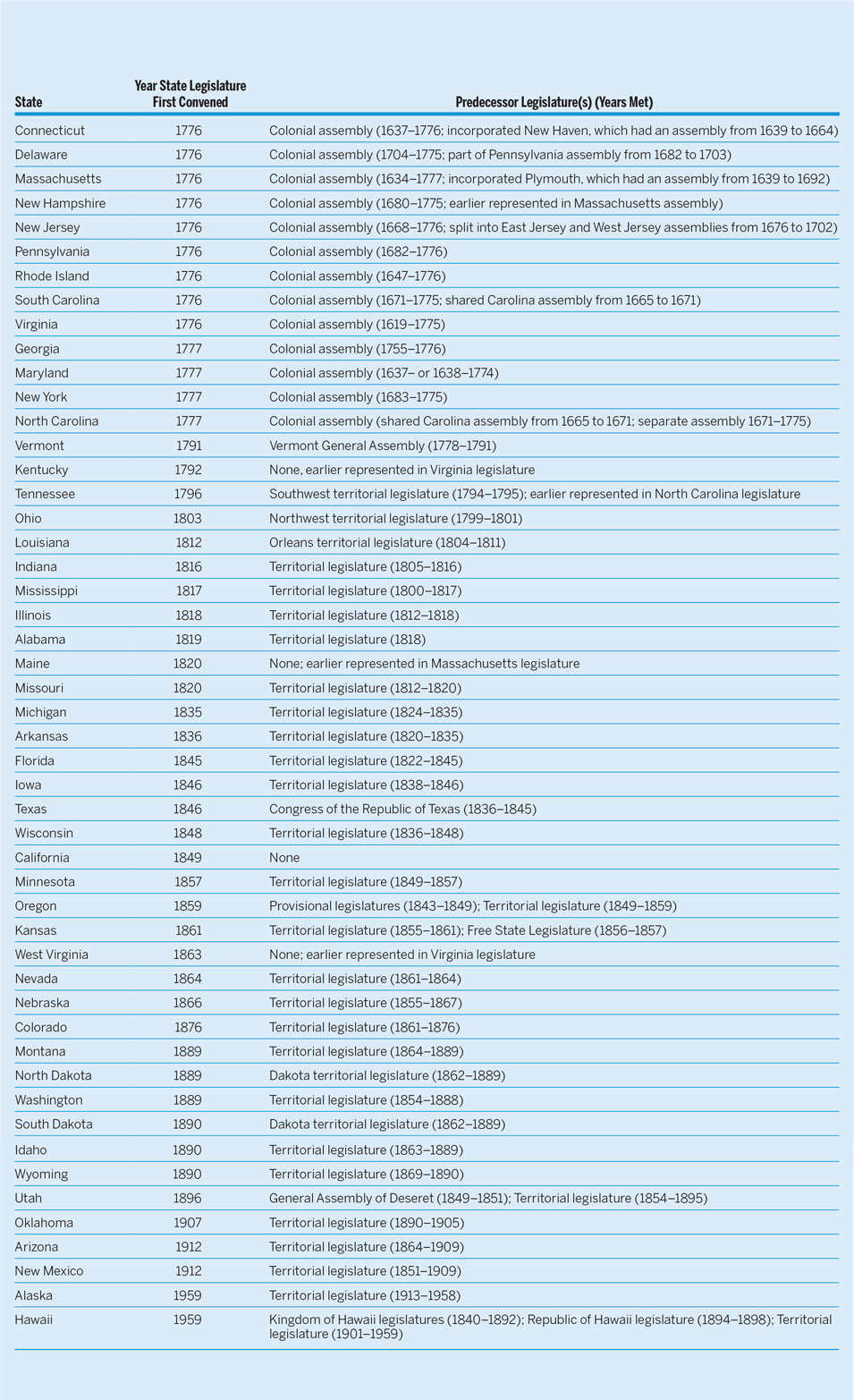

The later 37 state legislatures have different lineages than the original 13, as shown in table 1. A total of 31 emerged from territorial legislatures, which were created by Congress as part of the governing structure it enacted when territories were established. They played an important evolutionary role because their rules and committee structures transferred to the state legislatures that succeeded them.

Table 1 The Lineage of American State Legislatures

Source: Squire 2012; 2017.

Note: Some legislatures met prior to the state being formally admitted.

Several territorial legislatures were preceded by other legislative bodies that influenced their evolution. In Oregon, several provisional legislatures made laws while the United States and Great Britain were competing for political control. Before the creation of Utah Territory, Mormons founded the State of Deseret, complete with a bicameral assembly. The Hawaiian territorial legislature was preceded by several Kingdom of Hawaii legislatures and a Republic of Hawaii legislature; remarkably, the same standing committees carried through each legislature. In Kansas, the Free State legislature arose to not only challenge the proslavery territorial legislature but also to ultimately supplant it in the state legislature’s evolutionary line.

Six state legislatures had no colonial or territorial predecessor. Vermont and Kentucky became states before the territorial system was in effect. While it was independent, Vermont had a unicameral assembly, and the eastern portion of Kentucky had been represented in the Virginia legislature. Maine and West Virginia were detached from Massachusetts and Virginia, respectively: Maine’s legislature closely resembled its parent but West Virginia’s legislature drew on several models. The Texas state legislature was preceded by the Congress of the Texas Republic; the two institutions shared rules and committee systems. Only the California legislature did not have any predecessor to emulate.

THE EVOLUTION OF STATE LEGISLATURES

State legislatures continued to evolve during the nineteenth century. Bicameralism dominated, with every new legislature being established with two houses. Vermont, the lone unicameral body at the beginning of the century, became bicameral in 1836. Bicameralism was preferred because it was thought to promote greater scrutiny of proposed legislation.

In the early 1800s, almost every state legislature met annually because it was argued that frequent meetings checked gubernatorial power and enhanced representation (Squire and Hamm 2005, 68). However, a shift to biennial sessions took place over the course of the century. In 1832, only three of the then-24 states had biennial sessions: Illinois, Missouri, and Tennessee—all younger states that had established them in their first constitution. By 1900, only six of the now-45 states retained annual meetings, all of them from among the original 13 states. It was reasoned that biennial sessions produced fewer new laws, thereby fostering economic stability while also reducing costs associated with operating the legislature.

Other aspects of legislative life changed. State legislatures gained facilities dedicated to their use: 20 capitols that were built from the end of the eighteenth century through the nineteenth century are still in use by state legislatures. Staff resources improved. In the early 1800s, state legislatures enjoyed little assistance other than a clerk or two, a doorkeeper, and a sergeant-at-arms. The number of staff grew slowly. In 1858, the New York Assembly employed a clerk, four deputy clerks, a librarian, an assistant librarian, a postmaster, and an assistant postmaster. By 1890, the staff had swelled to 73 positions. Also, in that year, the New York State Library established a legislative reference unit, the first of its kind in the nation. In 1892, the Massachusetts State Library took similar steps. Both libraries provided lawmakers with information for use in devising and evaluating legislation.

State legislatures became more complex organizations during the nineteenth century, institutionalizing in much the same manner as Congress. In 1819, the mean number of rules across state lower houses was 37; by 1889, that number had increased to 64. The expanded rules focused on managing the legislative process, and some influenced developments in Congress: for example, House Speaker Reed’s landmark “disappearing quorum” ruling was grounded in state-legislative precedents (Squire 2013). Standing-committee systems also expanded; in 1819, every state legislature had at least a few standing committees. By 1889, the mean number had exploded to 33 and they had become central to the legislative process in every state, with most exercising gate-keeping powers that allowed them to kill bills.

Efficiency also was enhanced by the introduction of electronic voting, first used in the Wisconsin Assembly in 1917—more than a half-century before the US House installed such a system.

By the beginning of the twentieth century, state legislatures were quite different from what they had been a century earlier. They suffered, however, from a major problem: they were considered corrupt institutions and the public had little confidence in them. Yet, they—not Congress—determined many of the public policies that governed daily life. Consequently, citizens began to demand more of their legislature. This prompted efforts to improve legislative capabilities, culminating in the professionalization movement of the 1960s and 1970s.

In terms of basic structures, there were few changes in state legislatures during the twentieth century. The most substantial change occurred in Nebraska in 1934, when voters approved a constitutional amendment to create a unicameral legislature. At the same time, they also voted to make the legislature nonpartisan. Being unicameral and nonpartisan made (and still makes) Nebraska’s legislature distinctive. (Minnesota’s legislature was superficially nonpartisan from 1913 to 1973.)

The movement to biennial sessions reversed. By 1960, 19 state legislatures met annually; today, all but four do. States dropped biennial sessions (or the quadrennial sessions used in Alabama for several decades) for one main reason: increased policy-making demands required annual meetings to respond expeditiously.

In the early 1900s, legislative salaries were low: the mean across the states was slightly less than $250 a year. Observers argued that low pay promoted corruption. Consequently, reform advocates campaigned for higher wages and for replacing per diems with annual salaries. Their efforts met with some success: by the mid-1950s, the mean salary had increased to $1,188 and 31 states had replaced per-diem payments with a set wage. By 2018, 42 states paid an annual salary and the median had increased to $24,108. These changes have had an important consequence: since the 1930s, lawmaker turnover rates have declined noticeably.

In 1900, no state legislature provided staff for individual lawmakers and little assistance was provided to committees. Beginning in that decade, however, many states developed institutional informational resources. The most significant was Wisconsin’s Legislative Reference Bureau, which became a model not only for other states but also for what is today the Congressional Research Service. State legislatures also began to increase staffing in other areas. By the 1950s, clerical staff was provided to most committees in almost every state. Today, almost every legislature provides professional staff for standing committees and about half provide members with year-round personal staff.

State legislatures continued to evolve organizationally. At the beginning of the twentieth century, rules in most chambers were sophisticated and stable. From that point, their numbers grew, but only slowly, and occasionally the rules were substantially revamped. Additions and refinements focused on making the legislative process more efficient. Efficiency also was enhanced by the introduction of electronic voting, first used in the Wisconsin Assembly in 1917—more than a half-century before the US House installed such a system. Standing-committee systems experienced extensive changes. At the beginning of the century, they were bloated in most states. In 1915, for example, the 32-member Michigan Senate had 65 standing committees, 14 of which dealt with education issues. Similar peculiarities eventually forced most legislatures to streamline and rationalize their committee systems.

Currently, all but a few state legislatures still lag behind Congress in member pay, days in session, and staff resources (Squire 2017b). Yet, most are better equipped to meet the demands made of them than they were in the past. Their fundamental organizational and structural features, however, continue to be drawn from their colonial ancestors.