Previous studies point to a “gender citation gap” in the field of political science, broadly speaking, whereby female authors are disproportionately less likely than male authors to have their work cited. Specifically, when publishing original research, political scientists are less likely to cite studies conducted by women than by men (Dion, Sumner, and Mitchell Reference Dion, Sumner and Mitchell2018; Maliniak, Powers, and Walter Reference Maliniak, Powers and Walter2013; Mitchell, Lange, and Brun Reference Mitchell, Lange and Brun2013; Peterson Reference Peterson2018; see also Esarey and Bryant Reference Esarey and Bryant2018).Footnote 1 Also, political science instructors are less likely to cite women than men in their course syllabi, and they tend to assign textbooks and other readings in which women are underrepresented (Colgan Reference Colgan2017; Diament, Howat, and Lacombe Reference Diament, Howat and Lacombe2018; Phull, Cifliki, and Meibauer Reference Phull, Cifliki and Meibauer2018).Footnote 2

However, these studies examine the gender citation gap only among political science scholars; no previous study has examined whether and to what extent this gap also exists among political science students.Footnote 3 This article presents our analysis, focusing on undergraduate student research. Specifically, we use original data from an introductory political science research methods course to examine the relationship between student gender and gendered citation patterns. Our data are from two stages of an original research project, completed by students during the course of one semester. Students completed the first stage of this research individually and the second stage in groups, thereby enabling us to analyze citation patterns as a function of an individual student’s gender as well as group gender dynamics.

…we use original data from an introductory political science research methods course to examine the relationship between student gender and gendered citation patterns.

It is important to study the gender citation gap among political science students—and not solely among scholars—for three reasons. First, gender bias is unacceptable as a matter of equity, and it undermines students’ educational experience in political science. For example, the gender citation gap may be indicative of broader gender biases that negatively affect a classroom learning environment and, as such, cannot be tolerated or ignored. Also, discounting research conducted by women necessarily limits students’ understanding of political science research as a whole, which in turn should compromise the quality of their performance on research projects and overall educational experience. Thus, as a basic pedagogical matter, it is essential for political science instructors to understand how gender bias in any form—including the gender citation gap—manifests in the classroom and negatively impacts students.

Second, studying the gender citation gap in undergraduate student research would make a valuable contribution to combating implicit gender bias in the political science classroom. Indeed, this study provides evidence that might convince skeptical students (as well as some faculty) that such problems likely exist and should be addressed. Moreover, it could provide the impetus for political science instructors and departments to explore strategies aimed at doing so. For example, instructors might use this or similar studies to engage students in discussions of the gender citation gap before conducting political science research, whether in a traditional classroom setting or for an independent study or honors thesis. Instructors might even design experiments to test which type of intervention is most effective at reducing the gender citation gap among students, such as assigning a reading on the topic versus requiring them to analyze their own citation patterns from previous assignments.

Third, this research provides essential context for previous studies of the gender citation gap. Those studies, cited previously, demonstrate that political scientists generally engage in gendered citation patterns, which—among other things—may skew political science students’ perceptions of what qualifies as the most relevant scholarship in the field. Indeed, scholars’ citation patterns alone may be enough to have an effect. However, students are not blank slates. To the extent that they enter the classroom already inclined to discount women’s research, political scientists’ gendered citation patterns actually may be exacerbating an existing bias among students of which we are not yet aware. If so, then the gender citation gap among scholars may be even more problematic than previous studies indicate. Of course, our study is not designed to test for an interactive effect of students’ and scholars’ gendered citation patterns. However, this work can serve as a necessary first step toward researching such effects in the future.

DATA AND METHODS

The objective of this study is to determine whether—and, if so, to what extent—gender bias influences students’ citation patterns, specifically when citing women. Such biases may be evident in research conducted by individual students, by groups of students, or both. In other words, gender bias may influence how students conduct their own research and/or how they collaborate with others when conducting research. Either phenomenon may limit students’ exposure to female-authored research and perpetuate the gender citation gap.

To evaluate gender bias in student citations at the individual and group levels, respectively, we propose the following hypotheses: (1) male students are less likely than female students to cite research authored by women (hypothesis 1); and (2) groups with fewer female students are less likely to cite research authored by women (hypothesis 2). Both hypotheses are consistent with previous findings regarding gendered citation patterns among scholars (Dion, Sumner, and Mitchell Reference Dion, Sumner and Mitchell2018; Mitchell, Lange, and Brun Reference Mitchell, Lange and Brun2013).

To evaluate gender bias in student citations at the individual and group levels, respectively, we propose the following hypotheses: (1) male students are less likely than female students to cite research authored by women (hypothesis 1); and (2) groups with fewer female students are less likely to cite research authored by women (hypothesis 2).

Data for this analysis are from an original database of research projects completed as part of an undergraduate political science research methods course at a private Midwestern university. Our sample included all 140 students (65 women and 75 men) enrolled in one of seven course sections offered between spring 2017 and spring 2019. Each course section was taught individually by two of this article’s coauthors (one woman and one man).Footnote 4

During the course of one semester, students followed a scaffolded approach to complete an original research project. The first stage was an annotated bibliography that each student completed individually. The final stage was a 10-page research paper consisting of a literature review, research design, and data analysis, all of which were completed in groups of three to four students.Footnote 5 We used two research assignments integral to students’ development of the final project—the annotated bibliography and the literature review—as our data sources. For the annotated bibliography, each student located and summarized four or five peer-reviewed articles directly addressing a research question developed by the group to which he or she was assigned at the beginning of the semester. After completing the annotated bibliography, students then worked with their group members to write a literature review, citing 12 scholarly articles, that later would be incorporated into their final research paper. Because most groups included four students, and most students cited at least four articles in their annotated bibliographies, each group decided which articles to eliminate or retain for the literature review. They also could add new articles, which many groups did in response to the instructor’s feedback.Footnote 6 In total, the (individual) annotated bibliographies included 624 citations and the (group) literature reviews included 483 citations.

To test our hypotheses, we began by coding each author’s gender—or, at least, students’ likely perception thereof. Two graduate students (one woman and one man) coded each author by name, exactly as it appeared in a student’s or a group’s citation, as (1) certainly a man/woman (90% to 100% confidence); (2) probably a man/woman (60% to 90% confidence); or (3) indeterminable (less than 60% confidence).Footnote 7 For this analysis, we combined the certain and probable gender identifications so that each author was coded as a woman, a man, or indeterminable.Footnote 8 Next, we generated three measures of gendered citation patternsFootnote 9: (1) percentage of articles cited by a student or group in which the first author was a woman; (2) percentage of articles in which any author was a woman; and (3) average percentage of authors who were women, per article.Footnote 10

RESULTS

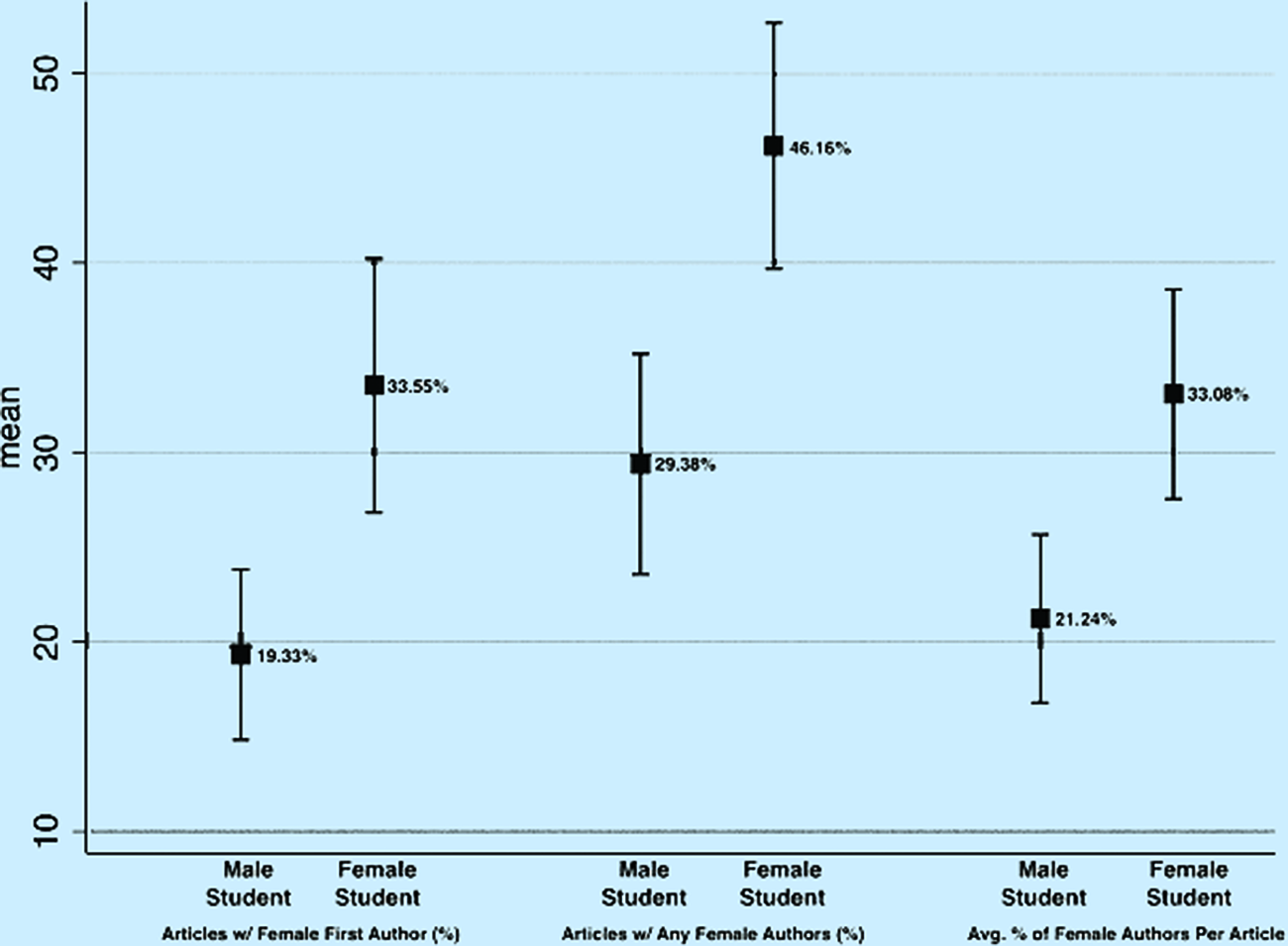

Figure 1 presents an initial indication of gender’s influence on student citation patterns. The figure lists the percentage of articles that male-versus-female students cited in their annotated bibliographies in which the first author or any author was a woman, as well as the average percentage of female authors per article. Figure 1 also includes 95% confidence intervals to indicate whether the percentages differed significantly based on a student’s gender. All three measures exhibit these differences. Specifically, there is a 14-percentage-point gender gap regarding first authorship; a 16-percentage-point gap regarding any inclusion of women; and an 11-percentage-point gap regarding the average share of female authors per article. In each case, male students were less likely than female students to cite research conducted by women.

Figure 1 Citation of Women’s Research in Male-versus-Female Students’ Annotated Bibliographies

However, there are good reasons to believe that other factors might confound—or at least weaken—the bivariate relationships in figure 1. First, some students’ research interests pertain to political science subfields in which women are more active and publish more frequently than other subfields. If female students, in particular, gravitate toward studying topics within these subfields, then that may explain the gender disparities shown in figure 1. Second, the college experience should increase students’ awareness of gender and other inequities such that more advanced students may be more sensitive and responsive to concerns about diversity and inclusion. Therefore, we might expect a fourth-year student’s citation pattern to be more gender-inclusive than that of a second-year student.

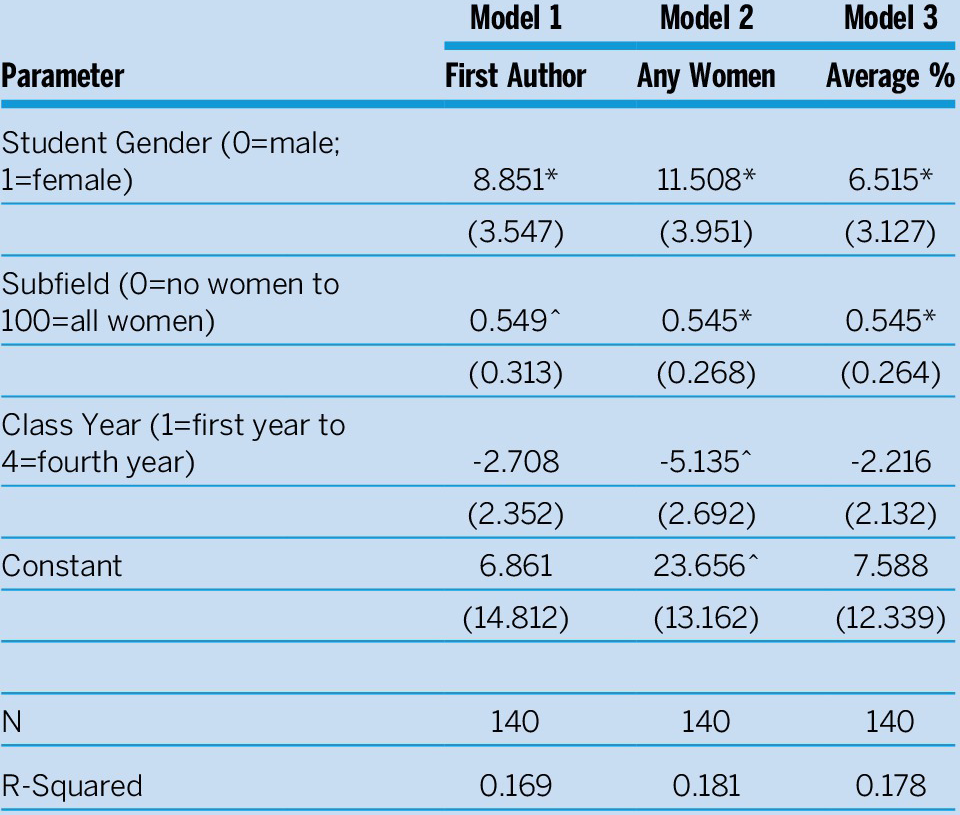

To account for potential confounders, we estimated three linear regression models. The dependent variables are the same as in figure 1. The independent variable is student gender (0=male, 1=female). Also, we included two control variables. First, to account for women’s subfield presence, we identified the APSA organized section most closely related to a student’s research topic. Then we recorded the percentage of women belonging to that organized section as of early 2019.Footnote 11 For example, a student whose research most directly pertains to “Human Rights” (Section 36) would be coded as 54.8% on the subfield variable because this is the percentage of section members identified as women. Second, we controlled for the student’s class year (1=first year through 4=fourth year). Table 1 presents the results from our regression models.

The student-gender variable is statistically significant at p<0.05 in each model, even after controlling for subfield and class year.Footnote 12 However, there are differences by student gender smaller than in figure 1. That is, the citation gap between female-versus-male students is 8.9 percentage points for first authorship; 11.5 percentage points for including any women; and 6.5 percentage points for the average share of female authors per article. Again, male students were less likely than female students to cite research conducted by women. This evidence clearly supports hypothesis 1.Footnote 13

Table 1 Citation of Women in Students’ Annotated Bibliographies

Notes: Entries are linear-regression coefficients. Robust standard errors are in parentheses. All observations are clustered by research group.

***p<0.001; **p<0.01; *p<0.05; ^p<0.10. The dependent variables measure gender diversity in student citation patterns. First Author (Model 1) represents the percentage of citations with a woman as first author. Any Women (Model 2) represents the percentage of citations including any woman as an author. Average % (Model 3) represents the average percentage of authors who were women, per article.

However, does gender bias likewise affect how students conduct research in collaboration with other students? In other words, does gender diversity influence group citation patterns with respect to gender, which seems to be the case for political scientists (Dion, Sumner, and Mitchell Reference Dion, Sumner and Mitchell2018)? To answer this question, first we needed to modify our data so as to treat the group’s (i.e., literature review) rather than the student’s (i.e., annotated bibliography) submission as our unit of analysis. Our independent variable measured the percentage of women within a group (i.e., 0=no women to 100=all women) rather than an individual student’s gender.Footnote 14 Also, we measured class year as the average for all group members. The subfield variable required no modification because its original measurement was based on the group’s research topic.

Finally, we calculated the dependent variables according to the difference between the percentage of women cited in the group’s literature review and their percentage cited in all of the individual group members’ annotated bibliographies combined. For example, suppose that a group of four students submitted a literature review in which three of 12 articles (25.0%) had any female authors, whereas those students’ annotated bibliographies, combined, included six of 16 articles (37.5%) with any female authors. This group would be coded as -12.5% on the “any” dependent variable (37.5% to 25.0%).Footnote 15 In other words, the group’s literature review was 12.5 percentage points less diverse, with respect to gender, than the original pool of citations.

To evaluate the relationship between the gender diversity of a student group and its citation patterns, we estimated three linear regression models (table 2). In each case, we found no evidence of any such relationship. That is, the percentage of women within a group had no discernible effect on how many women that group cited in its literature review, relative to the pool of citations with which it started.Footnote 16 This evidence does not support hypothesis 2. The gender bias that we observed so clearly in individual students’ research apparently does not extend to the collaborative research setting.Footnote 17

Table 2 Citation of Women in Group Literature Reviews

Notes: Entries are linear-regression coefficients. Standard errors are in parentheses. ***p<0.001; **p<0.01; *p<0.05; ^p<0.10. The dependent variables measure gender diversity in group citation patterns, relative to gender diversity in the group members’ individual citation patterns. Specifically, in each case, we subtracted the relevant measure as applied to all group members’ annotated bibliographies, combined, from that measure as applied to the group’s literature review. First Author (Model 1) represents the percentage of citations with a woman as first author. Any Women (Model 2) represents the percentage of citations including any woman as an author. Average % (Model 3) represents the average percentage of authors who were women, per article.

CONCLUSION

Overall, our results indicate that gender bias does influence undergraduate students’ citation patterns—but only at the individual level. Male students were less likely than female students to cite research conducted by women. However, within groups, we found no evidence that gender dynamics influenced the collaborative process such that male-dominated groups were more likely to exclude research conducted by women. The former result is consistent with previous evidence regarding political scientists’ citation patterns (Mitchell, Lange, and Brun Reference Mitchell, Lange and Brun2013) whereas the latter is not (Dion, Sumner, and Mitchell Reference Dion, Sumner and Mitchell2018).

Overall, our results indicate that gender bias does influence undergraduate students’ citation patterns—but only at the individual level.

We can only speculate as to why our evidence does not support hypothesis 2. One possibility is that whatever their private inclinations may be, students genuinely strive to include all members and their perspective when participating in group work—and they succeeded in doing so. Another possibility is that students simply were more intentional and more attentive to various details about a given article, including author gender, when conducting research individually compared to working in a group setting in which citation decisions might be deferred to other students. The latter explanation is plausible and could be tested easily using data from an alternative research assignment—for instance, one that requires the group to work together to locate articles for its literature review rather than drawing on a pool of citations from individuals’ annotated bibliographies. Future research would be valuable in exploring these possible explanations and in replicating our results across a diverse range of assignments and disciplines. Moreover, we recognize that this study is limited in terms of generalizability because our data are from seven sections of one course taught at one private Midwestern university. Additional studies replicating or extending our research design in other courses and institutions would strengthen our understanding of undergraduate students’ citation patterns and further address the gender citation gap in political science.

To the extent that women, in fact, are underrepresented in undergraduate student research, the question becomes: What do we, as a discipline, do about this? One practical response is for political scientists to evaluate whether they are setting a good example for their students by measuring the citation gap in their own research and syllabi (Sumner Reference Sumner2018) and making appropriate modifications. Another practical response is for instructors to explicitly address the gender citation gap with their students and encourage them to consider how gender biases might influence their work. Indeed, these are the types of interventions recommended to address the gender citation gap only among political scientists (Brown and Samuels Reference Brown and Samuels2019; Peterson Reference Peterson2018). If similar biases are evident among students, surely they would deserve our attention as well.

Supplementary Materials

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S1049096520000426.