Although the 2018 midterm elections were by all accounts a referendum on President Trump, this highly national election brought unusual interest in America’s quintessentially local office: the county sheriff. Hopkins (Reference Hopkins2018) defined political nationalization as a dual process of (1) convergence of local and national political conflict along a single dimension, and (2) intensified interest in national politics to the detriment of state and local politics. However, the link between the first and second points is empirical, not analytical. As I show in this article, in 2018, national politics infused sheriff races with new energy and outside money, reorienting ordinarily sleepy campaigns around a hot-button national issue: cooperation with federal immigration enforcement.

…in 2018, national politics infused sheriff races with new energy and outside money, reorienting ordinarily sleepy campaigns around a hot-button national issue: cooperation with federal immigration enforcement.

This linkage with immigration enforcement provided the “contest of evocative symbols” (Hopkins Reference Hopkins2018, 61) usually absent in local races, which allowed Democratic and progressive challengers to link their election with resistance to the president.

Under what conditions does nationalization increase attention to local politics? Using case studies of 2018 sheriff races, this article shows how this redirected nationalization results from newly salient national issues impinging on local government services and changing the strategic incentives of candidates. For sheriffs, renewed attention to immigration enforcement—reified by agreements between sheriffs and Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE)—provided the conduit through which nationalized politics defined local elections. This external change enabled savvy challengers to emphasize ideological and partisan differences—in other words, nationalize their races—to expand the scope of conflict against incumbents (Schattschneider Reference Schattschneider1960). I trace this process in primary elections, general elections, and even nonpartisan elections and show how in purple and blue counties with substantial immigrant communities, challengers who nationalized their races around immigration enforcement benefited electorally, which is consistent with theories of congressional elections (Stone and Simas Reference Stone and Simas2010).

The normative implications of redirected nationalization are ambiguous. Informative partisan labels can help align law-enforcement policies with voter preferences (APSA 1950). However, nationalization also can undermine accountability if local officials are evaluated not for their own behavior but rather the president’s. Moreover, overt politicization could erode the frequently espoused goal of law-enforcement practitioners to “keep the politics out of public safety.”

GOING NATIONAL AND A THEORY OF REDIRECTED NATIONALIZATION

Why might candidates invoke national politics in their appeals to voters in local races? “Going national”—that is, explicitly calling on voters to make up their mind about local races by considering the president—exemplifies a broader strategic behavior of invoking ideology. Theoretical (Ansolabehere and Snyder Reference Ansolabehere and Snyder2000; Groseclose Reference Groseclose2001) and empirical (Stone and Simas Reference Stone and Simas2010) literatures about strategic candidate behavior in congressional races predict that savvy challengers facing a valence disadvantage against incumbents might take more extreme ideological positions to compete on issues and attract activist support. Conversely, valence-advantaged incumbents pivot toward the middle, emphasize their experience, and downplay the importance of party politics in their job. This provides an opportunity for challengers to expand the scope of conflict (Schattschneider Reference Schattschneider1960). In nonpartisan races, the incentive to go national may be even greater because voters often are less informed and more influenced by incumbency (Hagensick Reference Hagensick1964; Schaffner, Streb, and Wright Reference Schaffner, Streb and Wright2001).

In 2018, sheriff candidates seemed to have strategically “gone national,” as these theories predict. Across primary, general, and nonpartisan counties, I find that challengers adopted ideological stances whereas incumbents emphasized nonpartisan obligations of the role.

CHANGING DYNAMICS OF SHERIFF RACES

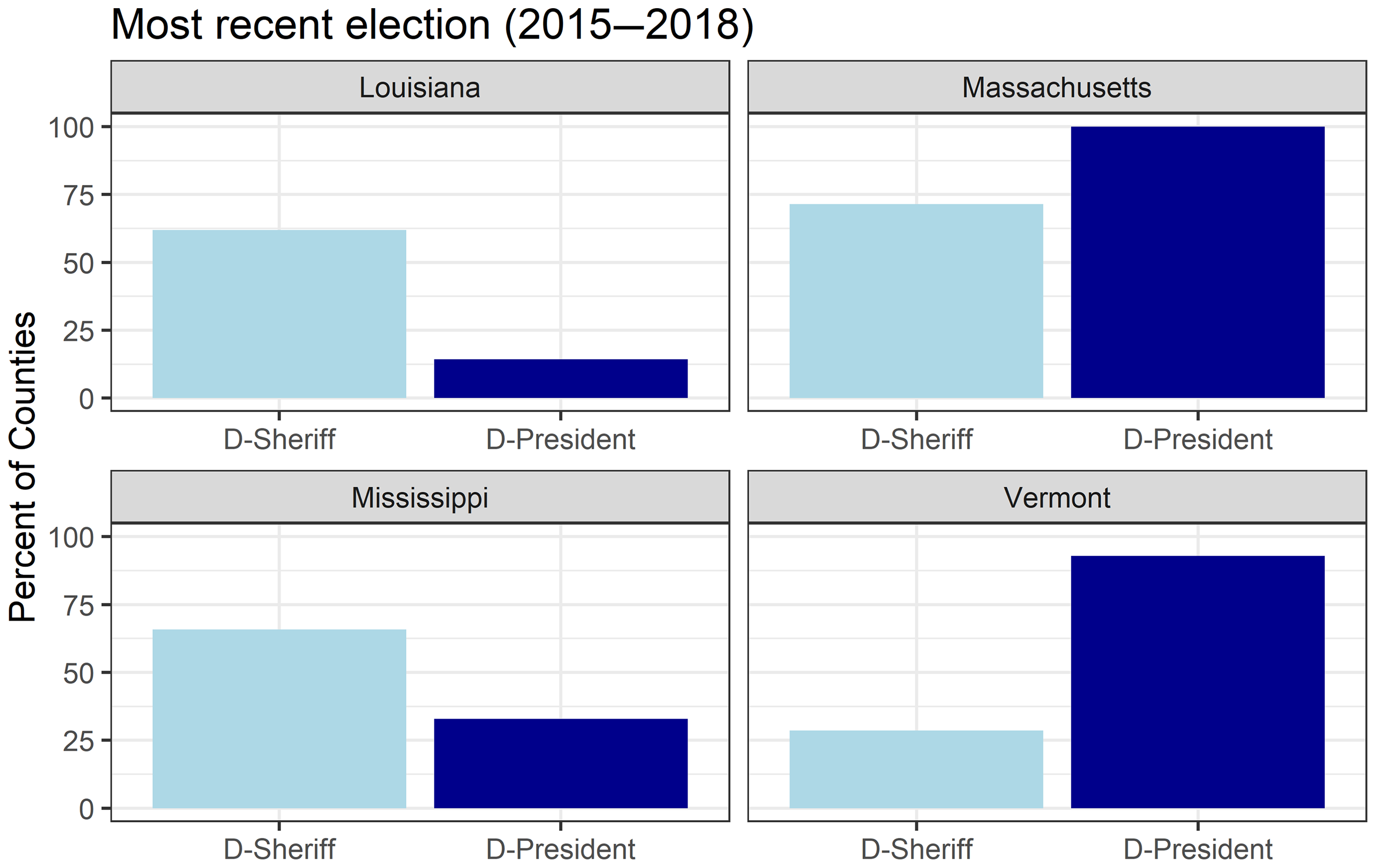

County sheriffs provide a difficult test for the theory because campaigns traditionally are played out over “local concerns and the personalities of those seeking office” (Crotty Reference Crotty1971) with candidates appealing to voters on their trustworthiness, connection to the community, and law-enforcement experience. The space for ideological debate in sheriff races is limited by the fact that “virtually all candidates for sheriff wisely promise to combat crime aggressively in their area” (Lublin Reference Lublin2007, 72). Consequently, sheriffs enjoy a buffer against the swings of national politics. In Massachusetts, for example, where all of the state’s 16 counties voted for Hillary Clinton in 2016, five counties reelected Republican sheriffs. Even today, contrasting with presidential voting, most sheriffs in Louisiana and Mississippi are Democrats, whereas most in Vermont are Republicans (figure 1).

Figure 1 Partisan Breakdown of Elected Sheriffs in Four States

However, that electoral buffer is facing new pressure as national politics filters downward (Hopkins Reference Hopkins2018). For sheriffs, who run the nation’s jails and operate much of its rural and suburban police forces, immigration enforcement drives that connection (Farris and Holman Reference Farris and Holman2017). Immigration gets at core questions of belonging—who is in the community and who is not—cleaving along social, racial, and political lines. When police aggressively investigate immigration status, questions arise about racial profiling and undermining the citizenship of ethnic minorities. When local law enforcement becomes tied to fears of deportation, citizens may be reticent to report crime to the police (Kirk et al. Reference Kirk, Papachristos, Fagan and Tyler2012).

Add to that the charged rhetoric of “Trump’s deportation force” and we get a toxic injection of national partisanship. Followed by intensified deportation efforts and administrative decisions designed to curtail immigration, the 2016 election catapulted immigration into the national consciousness. Because immigration enforcement is federalized and politically salient, the interplay between local police and federal immigration agencies provides an opening for political nationalization

Because immigration enforcement is federalized and politically salient, the interplay between local police and federal immigration agencies provides an opening for political nationalization (Gulasekaram and Ramakrishnan Reference Gulasekaram and Ramakrishnan2015).

(Gulasekaram and Ramakrishnan Reference Gulasekaram and Ramakrishnan2015). No institution embodies the national tension and polarization over immigration more than ICE. Within the latitude granted by state laws, sheriffs have discretion over cooperating with ICE. One channel is detainer requests, holding suspected undocumented immigrants in jail pending a federal investigation (Thompson Reference Thompson2020). A second channel is the 287(g) program, through which ICE authorizes and trains officers of local law-enforcement agencies to act as deputies—force multipliers for immigration enforcement. Some research points to political pressures galvanizing immigration-enforcement practices (Wong Reference Wong2012) whereas other work implicates the personal views of the county sheriff (Farris and Holman Reference Farris and Holman2017).

Under the Trump administration, the number of 287(g) agreements negotiated between the president and local sheriff offices has more than doubled, after declining somewhat at the end of the Obama presidency (The Economist 2018). These concrete connections with ICE make it easy to attribute local politicians with national politics. Michael Macleod-Ball, a political consultant and former legislative chief of staff at the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), explained that “287(g) is one of the few clear areas of intersection between the federal government and local government. Usually you can’t engage in a sheriff’s race and say, ‘look what’s happened to you and your community,’ and then tie that to particular issue voters know and care about on the federal level” (quoted in Madrid Reference Madrid2018). Within two years, 287(g) had shifted from a relatively unknown issue to the single issue deciding some sheriff elections (Boone Reference Boone2018). One headline even read, “How to Beat ICE in Your Hometown? Run for Sheriff” (Perry Reference Perry2018).

One consequence of nationalized politics is the increasing role played by national political organizations—and outside money—in local races (Reckhow et al. Reference Reckhow, Henig, Jacobsen and Litt2017). Liberal philanthropist George Soros was a first mover on sheriffs, pouring $2 million into a successful campaign to unseat hardline Republican and immigration-enforcement extremist Sheriff Joe Arpaio in the 2016 Maricopa County, Arizona, race (Bland Reference Bland2016). In 2018, liberal organizations, for the first time, poured money into sheriff races across states. The ACLU spent hundreds of thousands of dollars to oppose incumbent sheriffs with 287(g) agreements, finding a new role as a kingmaker in local electoral politics (Wallace-Wells Reference Wallace-Wells2018). The ACLU spent $175,000 on ad-buys and mailers in the Mecklenburg County, North Carolina, sheriff race and $140,000 in Wake County, North Carolina. An ACLU-backed group called Fairness Maryland spent $160,000 on ads and canvassing in an ultimately unsuccessful bid to unseat Frederick County Sheriff Chuck Jenkins (Madrid Reference Madrid2018). (Fairness Maryland apparently was formed for the sole purpose of influencing the 2018 Frederick County sheriff race.) Spending by the ACLU in these races dwarfs spending by candidates themselves: about triple the quarterly fundraising of the winner in Mecklenburg County (Seitz-Wald Reference Seitz-Wald2018) and 10 times the $15,000 raised during the entire campaign by the winner in Wake County (Molina and McDonald Reference Molina and McDonald2018).

Out of Step, Out of Office?

For sheriffs, partisanship has not always translated into policy making. The professional norms produced by a law-enforcement background, often a prerequisite for serving as sheriff, smooth over partisan differences (Thompson Reference Thompson2020). David Clarke, Milwaukee’s longtime conservative sheriff, repeatedly ran and won as a Democrat in a county dominated by Democrats. However, he also was an extremely conservative politician who told the Republican National Convention in 2016 that the only time he would reach across the aisle would be “to grab one of them by the throat” (Smith Reference Smith2017). Moreover, sheriff partisanship may not structure the way officeholders behave (Thompson Reference Thompson2020).

However, qualitative accounts of 2018 sheriff contests suggest that an important subset of these races has become more ideological and partisan. Several sheriffs faced tough challenges in the general election against candidates who invoked the national issues around immigration enforcement. Here, the partisanship of the candidates mapped onto real ideological differences about immigration policy. In Wake County, North Carolina, the Democratic challenger unseated longtime Republican Donnie Harrison with 55% of votes. The victorious Democrat promised that the 287(g) agreement would be terminated “as soon as we walk in the door.” In Frederick County, Maryland, the incumbent Republican ultimately prevailed—although with much-reduced margins—over an ACLU-backed Democratic challenger’s campaign that focused on ending the 287(g) agreement. Ideological contests for county sheriff, waged over the question of local cooperation with federal immigration enforcement, occurred in counties all around the country (Greenblatt Reference Greenblatt2018; Madrid Reference Madrid2018; Nichanian Reference Nichanian2018). Like the electorate more broadly (Schreckhise and Shields Reference Schreckhise and Shields2003), ideology and partisanship may be becoming increasingly intertwined for sheriffs.

Primary races also took on a more national quality. Some incumbent sheriffs lost in the primary to challengers who promised to decouple local resources from federal immigration enforcement. David Clarke’s chosen successor, Richard Schmidt, lost in the Democratic primary in 2018 after immigration activists linked him to President Trump with a photoshopped picture (Bice Reference Bice2018) and “hammered…his cooperation with federal Immigration and Customs Enforcement” (Graham Reference Graham2018). In North Carolina, two Democratic incumbent sheriffs lost their seats in primary races to more progressive candidates. In his victory speech, challenger Garry MacFadden proclaimed: “287(g) is going to be history in Charlotte-Mecklenburg. It’s going to be an event” (quoted in Boone Reference Boone2018). Clarence Birkhead, who also became Durham’s first black sheriff, “vowed to not cooperate with federal immigration officials” (Bridges Reference Bridges2018). In these races, the politics of the sheriff race became nationalized as local officials were brought into alignment with the national ideology of the Democratic Party.

Similarly, in Ulster County, New York, a state senate candidate said of the incumbent Paul Van Blarcum: “I would submit that our sheriff isn’t a Democrat, I don’t care what the label is” (quoted in Koronowski Reference Koronowski2018). The three-term incumbent who was criticized for meeting with President Trump resoundingly lost his renomination for the Democratic ticket to Juan Figurero, then ran as a Republican, and lost again to Figurero, who promised to reduce ICE cooperation. This cycle differed considerably from 2014, when the incumbent ran unopposed. Andrew Zink, president of Ulster County Young Democrats, explained that “Trump’s election woke people up. Trump made us look at these local issues and evaluate our local elected officials and ask ourselves, ‘Is this what we want?’ And when the Democratic voters of Ulster County looked at that question in that race, they said, ‘No, we don’t want our own Donald Trump’” (quoted in Holland Reference Holland2018). Figurero himself said that he “got interested in the race after the last presidential election” (quoted in Koronowski Reference Koronowski2018).

Partisanship in Nonpartisan Sheriff Races

Even in races in which party labels were not on the ballot, challengers galvanized their campaign by linking their race to national partisan battles. In a rare incumbent loss in Los Angeles County, politicos cited “cues [challenger Alex] Villanueva provided to voters about being a Democrat and taking a stand against immigration agents” as key to his successful challenge (Lau Reference Lau2018). His opponent, incumbent Jim McDonnell, called for keeping the office nonpartisan. Before 2018, no incumbent sheriff in Los Angeles had lost a reelection bid in more than 100 years. In Hennepin County, Minnesota, where local races are nonpartisan, challenger Dave Hutchinson unseated the 12-year incumbent Rich Stanek by earning endorsements from the state Democratic Party, local unions, and Hillary Clinton. Stating that “You will notice the difference between a Republican sheriff and a Democratic sheriff, a sheriff who stands with ICE and a sheriff who stands with immigrants,” Hutchinson pitched his candidacy as an opportunity to resist President Trump: “These local races now, with our current national administration, and the craziness that’s happening, this is how we can fight back.” Stanek countered that “When you call 911, you don’t press one for Republican and two for Democrat, because it is nonpartisan, and that’s how these races should be run” (quoted in Collins Reference Collins2018).

Accidental Upsets

The races described thus far demonstrate how renewed attention to local races injected national political debate, money, and activism into sheriff races. These races shared a salient connection to national politics over federalized immigration enforcement. However, counties that lacked this salient connection experienced the usual case of nationalization burying local politics. In partisan strongholds, this means that general elections coronated on-brand incumbents, but some swing counties had it different. In two suburban Colorado counties experiencing a “blue wave” in 2018, incumbent Republican sheriffs unblemished by scandal or controversy faced upset losses to cops from a small town with fewer residents than their new offices employed (Seaman Reference Seaman2018). A spokesperson for the defeated Adams County sheriff candidly voiced his frustration on Facebook, saying that “It makes me completely sick that some complete dumb ass will win as sheriff with no ability only—and I mean only—because he has a ‘d’ in front of his name.” The sheriff of Boulder County (a Democrat) expressed his “shock” over losing “top-notch sheriffs” to “a partisan wave,” saying that “in the office of sheriff, we come from different parties, but that doesn’t typically define how we work together” (Seaman Reference Seaman2018). The election prompted one town that had contracted out its police force to the sheriff since 2001 to consider rebuilding its police department (Schmelzer Reference Schmelzer2019).

CONSEQUENCES FOR ELECTORAL POLITICS

How do electoral results differ when local campaigns are nationalized? Incumbent sheriffs who run for reelection win more than 90% of the time (Zoorob Reference Zoorob2019). When politics is nationalized, however, incumbents are less safe. In 2018, in the dozen or so races in which media reports described immigration enforcement as the central issue, incumbents lost more than half of the time (figure 2). As Democratic consultant Mark Mellman warned, working with ICE is now perilous in Democratic counties: “Cooperate with Trump’s deportation squad and voters will punish you” (quoted in Greenblatt Reference Greenblatt2018). Where incumbents prevailed—often because a county was Republican-leaning (e.g., Frederick County, Maryland) or the incumbent was extremely well funded (e.g., Sheriff Chad Chronister of Hillsborough County, Florida, raised $1.3 million for his reelection, the biggest amount ever in the county)—their margins were much reduced.

Figure 2 Immigration-Based Sheriff Races in 2018

These local backlashes could seriously impede interior immigration enforcement. Because undocumented immigrants are even more concentrated in big cities than the general population (Passel and Cohn Reference Passel and Cohn2017), the very counties where it makes sense for ICE to develop formal cooperation with local authorities are those where electorates vote out officials who cooperate with ICE. This also highlights the scope conditions of nationalized immigration politics shaping local sheriff contests. National politics trickles down to these races proportionately to the salience of immigration and immigration enforcement—therefore, whereas sheriffs in North Carolina and Maryland were affected, those in Vermont (where sheriffs remain overwhelmingly Republican) and Mississippi (where they remain Democrat) were not.

Another scope condition is the presence of challengers. In Rensselaer County, New York—home to the state’s only 287(g) agreement—incumbent Republican Sheriff Patrick Russo coasted to reelection without an opponent in 2019 (he also ran unopposed in 2015). The county’s Democratic Party Chairman “thought Russo’s stance supporting 287(g) would have helped attract someone to run against him, but it didn’t” and cited a change in the state’s election calendar as hindering recruitment efforts (Crowe Reference Crowe2019).

CONCLUSION

The 2018 election was a national referendum on President Trump. Although nationalization typically buries interest in local politics, in this case, a highly national election redirected energy toward county sheriff elections, enabled by federalized immigration enforcement in county jails.

Although nationalization typically buries interest in local politics, in this case, a highly national election redirected energy toward county sheriff elections, enabled by federalized immigration enforcement in county jails.

Sheriff challengers accelerated this process by “going national” to expand the scope of conflict. With a Republican in the White House, this time it was Democratic and progressive challengers who defeated local incumbents by linking their struggles with nationwide resistance to President Trump. Voters in blue and purple counties terminated 287(g) agreements with ICE in Milwaukee, Charlotte-Mecklenburg, Anne Arundel, and Wake counties and empowered officials who promised to resist ICE cooperation in Durham, Hennepin, Los Angeles, and elsewhere.

In the long term, however, the increased responsiveness that results from political nationalization may come at the price of law enforcement—and, indeed, all local politics—becoming simply another front in the partisan fray. The theory of redirected nationalization applies equally well to district-attorney races, with “law-and-order” establishments upended by progressive challengers tapping into interest in criminal-justice reform. The trend of increasingly partisan and ideological sheriff campaigns appears poised to continue. Shortly after the November 2018 midterms, Josh King announced his candidacy for the 2019 sheriff race in Prince William County, Virginia, by “casting the election as a referendum on President Trump.” Hoping to build on recent Democratic shifts in the county’s presidential and gubernatorial vote, King—the first Democrat to run for sheriff in 16 years—stated that the county’s 287(g) agreement “needs to go.” The long-time incumbent Glendell Hill, a popular Republican, said that attempting to link him to Trump would be a mistake because voters know that partisan politics do not gel with local races. He countered that a sheriff’s “responsibility is to serve the citizens of Prince William County…not your party. The citizens” (Olivo Reference Olivo2018). Hill hung on with only 45% of the vote, defeating King (44%) and another challenger who opposed 287(g) (10%).