Social scientists produce research that aims to understand, explain, and help solve society’s most pressing problems. Practitioners have direct, field-based expertise on the nature of those problems and want to know what works.

Both groups are intensely curious. In some cases, they seek to establish extended collaborations in which they work together to conduct field experiments (Butler Reference Butler2019; Karlan and Appel Reference Karlan and Appel2016) and/or to engage in research–practice partnerships (Coburn and Penuel Reference Coburn and Penuel2016) and knowledge brokering (Dobbins et al. Reference Dobbins, Hanna, Ciliska, Manske, Cameron, Mercer, O’Mara, DeCorby and Robeson2009).

Yet, many researchers and practitioners may not have the need or capacity for extended collaborations. Instead, what they want—at least initially—are high-impact conversations. These conversations can reveal powerful new ideas. For instance, the “creative spark” for studying the impact of social pressure on voter turnout came from a conversation between political scientists and a campaign consultant in Michigan (Green and Gerber Reference Green and Gerber2010, 332).

Many researchers and practitioners may not have the need or capacity for extended collaborations.

This article describes a new evidence-based approach for initiating connections across diverse spaces called the Research Impact Through Matchmaking (RITM) method. It is rooted in research on organizational diversity because, at a fundamental level, connecting researchers and practitioners involves initiating new relationships between strangers who have diverse forms of knowledge (and who are often diverse with respect to many other attributes as well).

I applied RITM in the following setting. As president of research4impact,Footnote 1 I reached out to several practitioners’ listservs in 2018 and invited them to share challenges they were facing in their work in which they thought research might be helpful. In response, I connected them with a social scientist one on one. I targeted listservs composed of nonpartisan, nonprofit organizations with a mission to remedy social ills. Over three months, 37 practitioners responded. Details about the demand for and the results of these new connections are presented here.

I aim to make two contributions. One is that, to my knowledge, I present the first dataset that captures a wide variety of practitioners’ perspectives on the value of social science research. Second is that I describe the scientific foundations of RITM, give examples of its techniques, and present data on its impact.

This article has wide applicability. I identify several reasons why practitioners may want to connect with researchers. Each reason provides a potential basis for both to initiate their own new connections (i.e., match themselves) and/or broker new connections between others. My description of RITM then provides actionable guidance for how to achieve these goals.

HOW DO PRACTITIONERS AT NONPROFITS VALUE SOCIAL SCIENCE RESEARCH?

In 2018, I posted an announcement to five practitioner-oriented email lists inviting them to “learn about research that can help solve some of their organization’s trickiest problems.” The lists were composed of practitioners who work at nonpartisan, nonprofit organizations with a public-interest mission. They are advocates and organizers addressing social problems including poor nutrition, climate change, child abuse, low voter engagement, low political knowledge, traffic congestion, and pollution. The announcement asked them to fill out a brief online form. I then followed up for a more detailed scope call. During a three-month period, 37 people from 10 countries responded, and I connected them with researchers from 12 academic disciplines: public policy, public health, environmental studies, sociology, communication, economics, political science, psychology, law, business, city and regional planning, and human development.

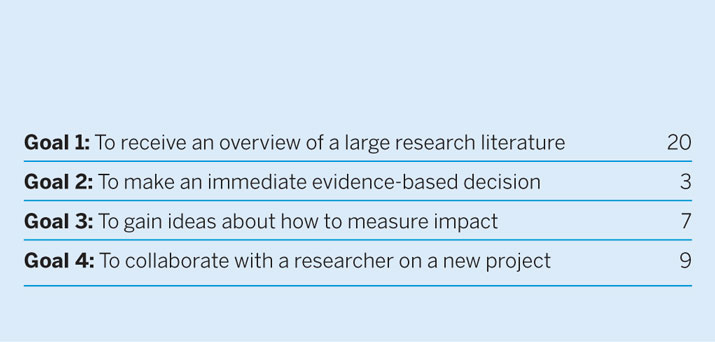

I categorized their requests into four types of goals (table 1). Those in the first three categories were matched with researchers for a conversation that typically lasted 60 minutes or less. Those in the fourth category also were matched for a conversation, at least initially, although with a stated interest in a longer-term collaboration.

Table 1 Goals of Nonprofit Practitioners

Numbers do not total 37 because two practitioners stated multiple initial goals.

Afterwards, I shared this coding with five professionals, each of whom had worked in advocacy and organizing for at least 15 years. All of them verified that it resonated with their personal experiences. Although this dataset surely is not representative of all practitioners who could benefit from connecting with a social scientist (i.e., it is difficult to imagine how this population would be defined), it does identify several reasons why a wide variety of practitioners value social science research, as follows.

To Receive an Overview of a Large Research Literature

This was by far the most common request: practitioners wanted a curated overview of a large body of literature. Typically, those who reached out were leading a new initiative within their organization. Although they could search online for relevant information, doing so entailed several concerns about volume and quality. A more efficient starting point would be a personalized conversation with a subject-matter expert in which they could learn about existing research most relevant to their goal. For example, one person was part of an organization that was beginning to give grants to local communities to spur civic engagement. She needed an overview of the latest research on links between civic engagement and public safety. A second person wanted to learn about research encouraging people to take public transportation and/or use bicycles instead of driving. Summing up his experience with a conversation like this, a third practitioner said: “We got a dose of years’ worth of research expertise in a 45-minute phone call.”

To Make an Immediate Evidence-Based Decision

Some practitioners were facing an immediate decision in their work and wanted to ensure that it was informed by evidence. For instance, one person who worked for a membership-based organization needed to measure members’ political ideology. His question pertained to survey methodology: What is the most effective way to measure how conservative or liberal someone is? Another person posed a survey question pertaining to networks of social-movement leaders: What is the best way to measure individuals’ social ties within a group? A third person was expanding her organization’s get-out-the-vote efforts and needed to learn about messages that resonate with low-propensity voters.

To Gain Ideas About How to Measure Impact

Some practitioners were seeking advice about how to measure the impact of their existing work. These questions arise internally within mission-driven organizations as well as externally from donors. In each case, they already were collecting some outcome data, but it did not always align most closely with their theory of change. If the initial conversation with the researcher went well, then they typically were open to a longer-term research collaboration.

For example, one person worked for an organization that had developed a new app to encourage healthy-eating behavior. It was easy to measure the number of users, but the organization’s ultimate goal was to change behavior. She wanted to talk with a researcher about possible behavioral measures. Another example came from someone who worked for an organization that provided online information about polling locations and candidates. He already had web-traffic data but wanted to assess the site’s impact on other outcomes, such as turnout and political trust.

To Collaborate with a Researcher on a New Project

Some practitioners reached out because they were interested in collaborating with a researcher on an entirely new project. In each case, they already had organizational, financial, and/or administrative resources in place and wanted to work with a researcher who would bring new ideas, research skills, and/or credibility. Unlike the previous category of respondents who only wanted to evaluate current programs, these practitioners expected to formulate new hypotheses in partnership with the researcher. For example, one person wanted to develop and test new ways of designing government forms for social benefits. Another wanted to brainstorm and test creative ways to raise awareness of economic insecurity among college students.

RESEARCH IMPACT THROUGH MATCHMAKING (RITM)

I developed RITM as a method for initiating new connections across diverse spaces, such as between these practitioners and researchers. RITM focuses on the initial setup: establishing a firm foundation for a successful relationship, whether it lasts for one conversation or extends further. RITM answers the question: What is the best way to initiate new relationships between diverse people? It is useful for individuals initiating their own new connections (i.e., matching themselves) and/or brokering connections between others.

RITM answers the question: What is the best way to initiate new relationships between diverse people?

On the one hand, conversations between diverse individuals can produce more creative and effective decision making (Sommers Reference Sommers2006) by surfacing a much broader set of perspectives and task-relevant knowledge (Galinsky et al. Reference Galinsky, Todd, Homan, Phillips, Apfelbaum, Sasaki, Richeson, Olayon and Maddux2015; Page Reference Page2017). On the other hand, people do not always feel comfortable sharing what they know, especially if status differentials are present (Stasser and Titus Reference Stasser and Titus2003), and diverse teams can produce interpersonal conflict (Galinsky et al. Reference Galinsky, Todd, Homan, Phillips, Apfelbaum, Sasaki, Richeson, Olayon and Maddux2015).

RITM maximizes the likelihood of informational gains and minimizes the possibility of tension and self-censorship. It entails two main steps: (1) defining the scope, and (2) making an introduction. The scoping techniques are useful for individuals initiating their own new relationships as well as those brokering new ones between others. The techniques for making introductions are useful when brokering new relationships.

The following discussion describes how I applied RITM during the 37 matches mentioned previously (i.e., from the perspective of one who conducted outreach to practitioners and whose goal was to broker new relationships between them and researchers other than myself). That said, each relationship-building technique discussed is easily adapted more broadly.

Defining the Scope

My use of RITM began once practitioners responded to my email-list outreach. I arranged a call to learn more about their goals. During this scope call I began with an “opener” that prompted the practitioner to speak first. People are more willing to share information with others who explicitly signal that they want to listen and be helpful (Miller et al. Reference Miller, Berg and Archer1983). The opener invited them to share more details about their organization, their role within it, and how research could be helpful.

Ensuring that the practitioner spoke first also was vital because of conversational dynamics. As Pickering and Garrod (Reference Pickering and Garrod2004) showed, individuals engaged in dialogue often pursue “interactive alignment” in which they align their language with what was said beforehand. During the scope call, this ensured that I was using similar language as the practitioner and also minimized my unintentional use of jargon (e.g., “experiment” and “subjects”).

As the conversation proceeded, follow-up questions were affirming and responsive to the information being shared. People are more willing to share detailed information with those who explicitly demonstrate interest and offer positive feedback (Taylor, Altman, and Sorrentino Reference Taylor, Altman and Sorrentino1969).

After conversing a while, it was important to recap the practitioner’s goals in my own words. This forced a higher level of active processing (Petty, Haugtvedt, and Smith Reference Petty, Haugtvedt, Smith, Petty and Krosnick1995) and ensured accurate understanding. I then asked practitioners to share the “ways in which what I said were either inaccurate or correct.” Survey researchers find that the wording of questions affects the types of considerations that are salient when people respond (Tourangeau, Rips, and Rasinski Reference Tourangeau, Rips and Rasinski2000). Deliberately phrasing the question in this way encouraged practitioners to canvass both types of considerations and also reduced the likelihood that they would “go along to get along” (Chen, Shechter, and Chaiken Reference Chen, Shechter and Chaiken1996) by not offering corrections.

Finally, during the scope calls, I was careful to avoid prematurely pressuring practitioners into a match. I asked whether they “are ready for a match or want to wait” while also noting that it is “totally understandable if they want to wait.” Here, I was leveraging normative language to legitimize the option of waiting. In this case, five of the 37 practitioners decided to wait.

Making an Introduction

After the scope call, the next step was to recruit a researcher with topical expertise who was likely to enjoy speaking with and learning from the practitioner. Then I formally introduced them via email.

The success of an introduction like this depends not only on who is recruited but also how they are recruited and how they are introduced to one another. In advance of diverse conversations, people often think about what they are going to say (Loyd et al. Reference Loyd, Wang, Phillips and Lount2013); how the interaction is framed affects this pre-meeting elaboration (Vorauer, Gagnon, and Sasaki Reference Vorauer, Gagnon and Sasaki2009). For this reason, RITM entails the following three techniques when brokering new relationships.

State Each Person’s Unique Expertise

People often do not share unique task-relevant information that they bring to a conversation, and others may not consider it carefully even when they do share it (Stasser and Titus Reference Stasser and Titus2003). Moreover, status differentials exacerbate these patterns. When people join task-oriented conversations, they enter with performance expectations. These are based on “shared cultural beliefs” that accord certain individual characteristics with “greater social worthiness and competence” and they are impactful because (Ridgeway Reference Ridgeway, Hogg and Scott Tindale2001, 357):

The greater the expectation advantage of one actor over another, the more likely the first actor is to be allowed chances to perform in the group, the more likely she is to speak up and offer task suggestions while the second actor hesitates, the more likely she is to have her suggestions positively evaluated, and the less likely she is to be influenced when there are disagreements.

In the United States, for example, several characteristics frequently inform these expectations, including educational attainment, occupation, gender, and race (Ridgeway Reference Ridgeway, Hogg and Scott Tindale2001). Researcher–practitioner relationships often differ along some of these lines.

One way to reduce the impact of status differentials is to communicate upfront each individual’s expertise to the entire group. As Sunstein and Hastie (Reference Sunstein and Hastie2015, 112) wrote: “If a group wants to obtain the information that its members hold, all group members should be told, before deliberation begins, that different members have different, and relevant, information to contribute.” This method increases the likelihood that everyone shares their unique information and that others incorporate it into the broader conversation (Stasser, Stewart, and Wittenbaum Reference Stasser, Stewart and Wittenbaum1995). For this reason, my recruitment and match emails included short paragraphs that explicitly identified each person’s task-relevant expertise. I minimized biographical details, thereby speaking about expertise mostly in terms of what people have done (e.g., conducted research on x, led a new program on y) and not who they are (e.g., a professor, a program manager).

Describe the Conversation as a Mutually Beneficial Learning Opportunity

Focusing on each person’s task-related expertise also allowed me to frame the match as an opportunity for both the researcher and the practitioner to learn from one another (i.e., by stating that they will “enjoy talking to one another” and both “learn a lot”). As Galinsky et al. (Reference Galinsky, Todd, Homan, Phillips, Apfelbaum, Sasaki, Richeson, Olayon and Maddux2015) noted, leaders should ensure that a diverse work group “is framed inclusively, highlighting the benefits” for everyone involved. Ely and Thomas (Reference Ely and Thomas2001, 266) echoed this point, noting that leaders should encourage group members to work within a “cognitive frame” that explicitly values the opportunity to learn from one another. They observed that a “learning” frame produced high-functioning work groups in which members were more likely to feel valued and report that the group was successful.

Restate the Goal of the Conversation

In my emails, I took care to restate the goal of the initial conversation (based on what I learned during the scope call) to ensure that it was always common knowledge. As Phillips (Reference Phillips and Page2017, 241) wrote, “Having a common goal is one of the most important prerequisites for success in groups…repeat it often.” This provides an opportunity to explicitly convey not only that each person has expertise but also how that expertise is useful for achieving the conversation’s goal. It also provides a clear benchmark for post-conversation evaluation.

In summary, RITM leverages these three techniques when making introductions and, along with scoping techniques, provides a strong foundation for initiating new relationships between diverse people.

ASSESSING RITM’S IMPACT

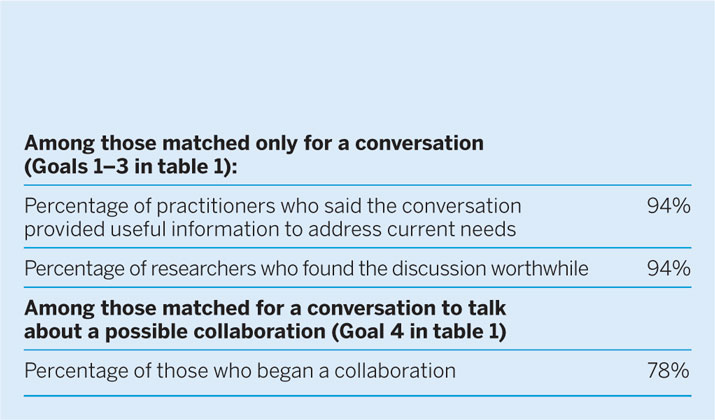

I applied RITM to the 37 practitioner-initiated requests and then assessed the matches in several ways (table 2). First, for the nine practitioners who wanted to talk about collaborating on a new project, seven (78%) had proceeded to the design and/or data-collection stage as of this writing. Six involve new data collection—likely randomized controlled trials (RCTs)—and one involves analyzing administrative data. In the other two cases, the researcher and the practitioner spoke amicably several times but could not agree on a mutually beneficial project.

Table 2 Summary of RITM’s Impact

In addition, there were 30 requests for conversations on other topics, of which 25 asked to be matched after the scope call (the other five chose to wait for various reasons); I found matches for 24. Afterwards, I followed up with practitioners and asked if the conversation provided useful information addressing their current needs. Two did not respond, and I learned that misconnects had occurred in four other cases (in which the practitioner and the researcher never spoke). Of the 18 that connected and responded, 94% responded affirmatively and noted that they would be using the information going forward. I also asked the researchers if the conversation was worthwhile. Again, 94% reported that it was, using phrases such as “gave me lots of ideas,” “helpful,” and a welcome opportunity to reflect on “what we know and what we don’t know.” Overall, this feedback provides strong initial evidence that RITM provided direct and immediate mutual benefits. Future work would benefit from applying it with an even wider range of practitioners, comparing demand among those who receive alternative outreach messages (perhaps via an RCT), and comparing outcomes among those who benefit from the evidence-based RITM method versus other matchmaking approaches (also perhaps via an RCT).

To conclude, relationships between researchers and practitioners fill important needs. They provide private benefits such as knowledge gained and they contribute to a broader norm of interaction: a public benefit.

...relationships between researchers and practitioners fill important needs. They provide private benefits such as knowledge gained and they contribute to a broader norm of interaction: a public benefit.

For researchers, these relationships complement other forms of engagement such as blogging (Sides Reference Sides2011), writing policy briefs (Skocpol Reference Skocpol2014), and performing public service (Bowers and Testa Reference Bowers and Testa2019). As external bodies (e.g., donors and governments) increasingly demand evidence of research impact (Nyhan, Sides, and Tucker Reference Nyhan, Sides and Tucker2015), it represents one way for research to influence decision making outside of the academy (Nutley, Walter, and Davies Reference Nutley, Walter and Davies2007) and for practitioners to efficiently learn what works. Finally, as interest in academic–practitioner relationships grows (Butler Reference Butler2019; Han and Stenhouse Reference Han and Stenhouse2015), RITM principles may be applied to other types of matches with various practitioners and extended to provide support beyond the initial match.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

For feedback and intellectual inspiration, I owe many thanks to Carina Barnett-Loro, Jake Bowers, Dan Butler, Bryce Corrigan, Liz Gerber, Don Green, Hahrie Han, Dan Hopkins, Brendan Nyhan, Michael Silberman, and Amber Wichowsky. I also thank the Rita Allen Foundation and Sage OCEAN for generous funding that made this project possible.