A pessimistic view of the potential of deliberative mini-publics to effectively contribute to democratic decision making on highly contested issues in deeply divided places asserts that (1) deliberative quality would be low due to the bitterness prompted by discussion of divisive issues, and (2) levels of opinion change would be low given the stubbornly enduring nature of political attitudes in divided places. We empirically examined this pessimistic view using a quasi-experiment involving mini-publics on two separate issues in Northern Ireland: (1) the contentious ethno-national question of Northern Ireland’s constitutional status, and (2) the much less contested and non-ethno-national issue of social care. Contrary to the pessimistic view, we find evidence that from the perspective of the participants themselves, deliberative quality was higher in the mini-public on an ethno-national issue. However, in line with the pessimistic view, levels of self-reported opinion change were significantly lower in the ethno-national mini-public. Overall, the findings highlight the potential for carefully designed deliberative mini-publics to address divisive ethno-national issues: they provide a space for participants to engage with such issues in open and respectful discussion—even if the prospects for attitudinal change are more limited.

Around the world, deliberative mini-publics have become an increasingly popular way of consulting citizens on a range of political issues, which supplements conventional representative institutions. In general, these democratic innovations illustrate the potential to realize some of the core ideals of deliberative democracy (Dryzek et al. Reference Dryzek, Bächtiger, Chambers, Cohen, Druckman, Felicetti and Warren2019). In the United Kingdom, citizens’ assemblies recently have been commissioned by the UK Parliament, the devolved governments of Scotland and Wales, and a range of local councils. However, much of our knowledge about the positive effects of mini-publics—from a deliberative perspective—is based on evidence from cases in relatively stable political contexts. This article asks: Do the same findings hold when mini-publics are conducted in a deeply divided political context?

We analyzed survey data from participants who took part in two separate mini-publics held in the postconflict context of Northern Ireland, a part of the United Kingdom where ethno-national identity continues to be a highly salient source of division (Garry Reference Garry2016). By comparing the attitudes of participants who took part in a mini-public on an issue without a direct ethno-national dimension (i.e., social care for older people) and those who took part in a mini-public on an issue explicitly connected to ethno-nationalism (i.e., Northern Ireland’s long-term constitutional status), we could examine the extent to which the nature of the issue affects subjective evaluations of the process and its impact. Contrary to our expectations, we found that perceived deliberative quality in the constitutional-status mini-public was higher compared to the social-policy mini-public. Furthermore, although there is evidence of self-reported opinion change in both mini-publics, our study found that levels were significantly lower in the constitutional-status mini-public.

MINI-PUBLICS IN THEORY AND PRACTICE

Deliberative mini-publics are not synonymous with deliberative democracy (O’Flynn Reference O’Flynn2022) but they constitute relatively small forums in which key deliberative principles may be realized under carefully designed conditions. We can consider the operation of mini-publics as a process involving three core stages: input, throughput, and output (Easton Reference Easton1965). In the input stage of the process, participants are selected at (near) random to achieve a broadly representative sample of the wider population. They attend simply as members of the public who express their own views as free agents rather than as delegates of a particular political party or interest group. In reality, some individuals are more likely to accept an invitation to take part, including older people, individuals with higher levels of education, and those with higher levels of political interest (Fournier et al. Reference Fournier, van der Kolk, Kenneth Carty, Blais and Rose2011). Appropriate incentives and stratification for relevant characteristics can minimize selection bias; however, in the latter case, the organizers of a mini-public still must determine what these stratification variables should be (Fournier et al. Reference Fournier, van der Kolk, Kenneth Carty, Blais and Rose2011).

Nevertheless, the broadly representative nature of a mini-public’s membership lays the foundation for inclusive and unconstrained deliberation at the throughput stage of the process. As Fishkin (Reference Fishkin2018, 21) pointed out, at the root of deliberation is “weighing”: after being presented with all of the relevant information—usually by independent experts and sometimes a range of stakeholders as well—the participants should sincerely weigh the arguments based on their merits in discussions with one another. For participants to be able to meaningfully engage in this discursive environment, it is important that they feel comfortable sharing their perspectives with other participants. Relatedly, mini-public deliberation should be marked by mutual respect, which is a central concept in deliberative theory (Gutmann and Thompson Reference Gutmann and Thompson1996). Indeed, as Polletta and Gharrity Gardner (Reference Polletta, Gardner, Bächtiger, Dryzek, Mansbridge and Warren2018, 71, emphasis added) stated, for discussion among participants to be “genuinely deliberative,” it must be “open to all” and should be as unconstrained as possible, consistent with “the requirement of civility.” Trained facilitators play an important role in this regard (Landwehr Reference Landwehr, Grönlund, Bächtiger and Setälä2014).

Finally, whereas deliberation occurs in many forms beyond mini-publics—sometimes without a specific goal in mind—mini-publics necessarily are oriented toward some type of output that records the collective opinions of the participants. Whereas the purpose of a standard opinion poll is to uncover the distribution of raw public opinion on a particular issue, the goal of a mini-public is to reveal the considered collective opinion of a broadly representative group of citizens, underpinned by the combined principles of political equality and deliberation (Fishkin Reference Fishkin2018). Consequently, if deliberation has an effect on the opinions of mini-public participants—as a type of treatment that is administered only within the mini-public environment—we usually would expect to observe changes in policy attitudes among at least some members. In fact, empirical studies have consistently found evidence of opinion change (Fishkin Reference Fishkin2018; Fournier et al. Reference Fournier, van der Kolk, Kenneth Carty, Blais and Rose2011; Suiter, Farrell, and O’Malley Reference Suiter, Farrell and O’Malley2016).Footnote 1

MINI-PUBLICS IN DEEPLY DIVIDED CONTEXTS

The principles of deliberative democracy can be more difficult to apply in deeply divided polities than in places with less (ethnically) polarized populations. Particular challenges may arise from group segregation, poor intergroup relationships, and the spillover of ethnic ideological divisions into a range of other political dimensions. Indeed, mini-publics that were held in these settings produced mixed results. In Belgium, Caluwaerts (Reference Caluwaerts2012) found a higher quality of deliberation in ethno-linguistically heterogeneous groups compared to ethno-linguistically homogeneous groups. A further study demonstrated the positive effect of deliberation on intergroup attitudes among mini-public participants—even on polarizing political issues (Caluwaerts and Reuchamps Reference Caluwaerts and Reuchamps2014). However, other empirical studies found either an increase in polarization and intergroup prejudice after deliberation (Wojcieszek Reference Wojcieszak2012) or highlighted the limited potential for citizen deliberation in the absence of certain conditions, such as a basic threshold of intergroup trust (Ugarriza and Nussio Reference Ugarriza and Nussio2016). Although O’Flynn and Caluwaerts (Reference O’Flynn, Caluwaerts, Bächtiger, Dryzek, Mansbridge and Warren2018, 749) suggested that, perhaps surprisingly, there are greater grounds for optimism than pessimism, they contend that scholars should “be cautious or circumspect in drawing conclusions about the potential for deliberation in divided societies.” We agree and focus our attention on the question of what types of issues mini-publics may tackle constructively in such contexts. If they tackle ethnically contentious issues, can a sufficiently deliberative environment be maintained?

This article assesses the differences in mini-publics in deeply divided places across two different types of issues: one that is ethnically contentious and one that is not ethnically contentious. Given the somewhat mixed empirical evidence to date, our hypotheses err on the side of caution. First, we expect the nature of the issue to affect the quality of deliberation in the mini-public. Specifically, we expect deliberative quality (in terms of both participants’ perceptions of freedom to express themselves and the extent to which views are respectfully discussed) to be lower in a mini-public tackling an ethnically contentious issue than in a mini-public tackling a non-ethnically contentious issue (Hypothesis 1). Second, we expect the nature of the issue to affect the extent of subjective opinion change, with such changes being less prevalent in a mini-public considering an ethnically contentious issue compared to one addressing an issue that is not ethnically contentious (Hypothesis 2). Third, we expect that any observed effects may vary depending on whether the participants prioritize their ethno-national ideology. Specifically, we expect that in a mini-public dealing with an ethnically contentious issue compared to one dealing with another issue, levels of perceived deliberative quality (Hypothesis 3a) and subjective opinion change (Hypothesis 3b) will be lower among individuals for whom the ethno-national dimension is salient.

TWO CASES IN NORTHERN IRELAND

We tested our hypotheses in the deeply divided context of Northern Ireland, where two mini-publics took place on different topics within five months of one another. In the autumn of 2018, the first Citizens’ Assembly for Northern Ireland was held on the issue of social care for older people as part of a civil-society initiative.Footnote 2 The online panel of a survey company, LucidTalk, recruited 75 participants to broadly reflect the demographic characteristics of the Northern Ireland population. They met over the course of two weekends at a hotel in central Belfast, with evidence presented by a range of experts and stakeholders. The Citizens’ Assembly produced a wide range of recommendations, which were published in an official report (Involve 2019). The issue of social care is politically sensitive but does not have any clear ethno-national ideological dimension in Northern Ireland; it may be considered primarily a crosscutting issue.

In March 2019, a deliberative forum was held on the issue of Northern Ireland’s long-term constitutional status as part of an academic exercise.Footnote 3 Quota sampling by Ipsos-MORI recruited 49 participants to be broadly representative of the Northern Ireland population according to gender, age, social class, geographical location, and community background. They met for one day at a hotel in central Belfast. The session focused on the possible governing models that could emerge in the event that a majority in Northern Ireland (as well as a majority in the Republic of Ireland) voted in favor of Irish unification in a future referendum. Expert presentations compared and contrasted the scenarios of a devolved united Ireland and an integrated united Ireland against the status quo of Northern Ireland remaining in the United Kingdom. The issue of Northern Ireland’s long-term constitutional status is highly salient and highly contentious along ethno-national lines. Unionists, who overwhelmingly tend to be Protestant, support Northern Ireland’s position in the United Kingdom. Nationalists, who are overwhelmingly Catholic, support Northern Ireland leaving the United Kingdom to unify with the Republic of Ireland. However, the ethno-national dimension is not highly salient for all individuals; a significant minority identify as neither nationalist nor unionist (Hayward and McManus Reference Hayward and McManus2019).

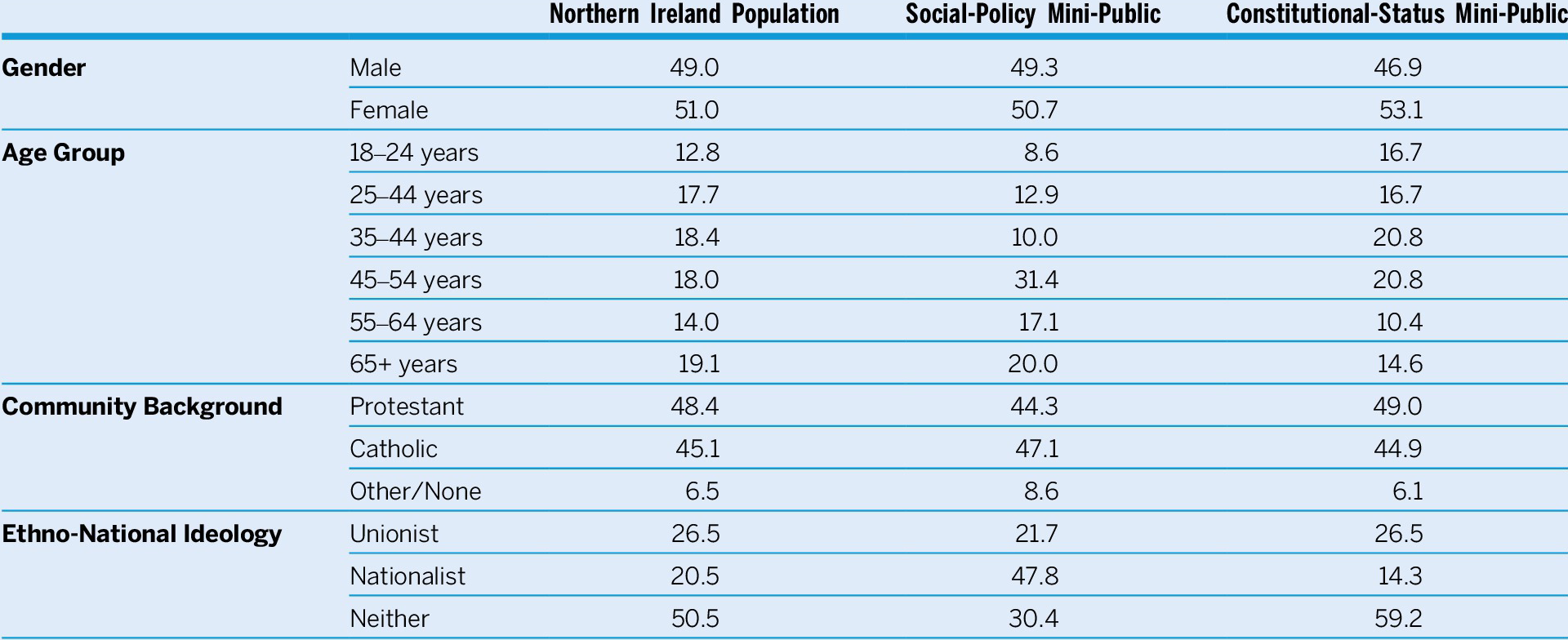

Thus, by addressing two contrasting issues, these two mini-publics allowed us to test our hypotheses using survey data collected from the participants at the end of each event. The mini-publics were independently organized; therefore, the research design is not directly experimental. Rather, the two mini-publics were significantly similar in core respects, such as their composition (table 1) and the fact that both were commissioned by nongovernmental bodies, but they vary on the type of issue being considered.Footnote 4 We characterize our analysis as quasi-experimental.

Table 1 Composition of the Northern Ireland Population and Each Mini-Public by Gender, Age Group, Community Background, and Ethno-National Ideology (% Distribution)

Sources: Involve (2019) and authors’ data (Pow and Garry Reference Pow and Garry2023).

PERCEIVED QUALITY OF DELIBERATION

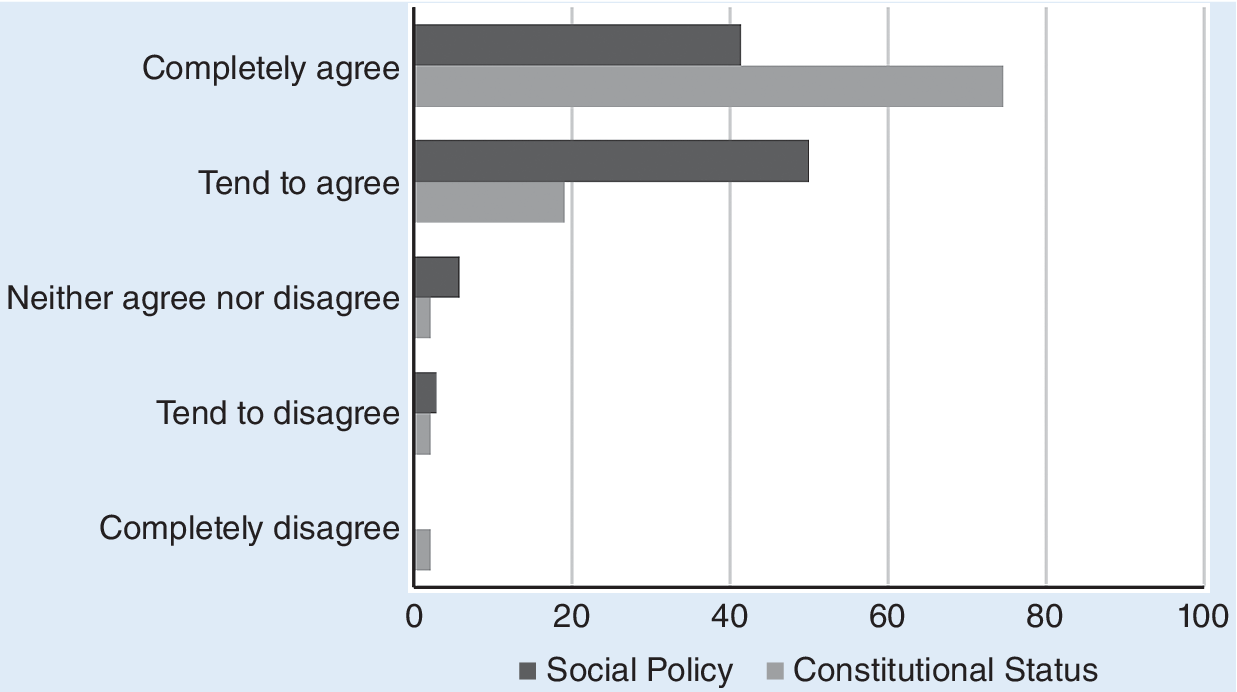

We tested our first hypothesis with two measures of perceived deliberative quality: the extent to which participants agreed or disagreed that (1) they could express their opinions, and (2) deliberation was respectful. Figures 1 and 2 present the distribution of participants’ responses in each mini-public. In both cases, we observed a similar pattern. First, the majority of participants in each mini-public agreed that they could freely express their opinions (between 93% and 98%) and that discussions were respectful (between 91% and 94%). Second, for both measures, the intensity of agreement was stronger in the constitutional-status mini-public than in the social-policy mini-public. This is contrary to Hypothesis 1: the perceived quality of deliberation was actually higher in the mini-public that addressed an ethnically contentious issue. These differences are statistically significant, as determined by Mann-Witney U tests for a perceived ability to express opinionsFootnote 5 and a perceived sense of respect.Footnote 6

Figure 1 Extent to Which Participants Agreed or Disagreed That They Could Express Their Opinions (%)

Figure 2 Extent to Which Participants Agreed or Disagreed That Deliberation Was Respectful (%)

Concerning Hypothesis 3a, we considered variation in perceived deliberative quality between the two mini-publics according to ethno-national ideology. Here, our findings also were unexpected. Among both nationalist and unionist participants, there were no significant differences in how they evaluated how free they were able to express their opinionsFootnote 7 or in the perceived level of respectFootnote 8 between each type of mini-public. However, for each of these two indicators, perceived deliberative quality was significantly higher in the mini-public on the constitutional issue (compared to the mini-public on social policy) among participants identifying as neither nationalist nor unionist (i.e., those for whom the ethno-national issue lacks the salience to define their identity).Footnote 9

OPINION CHANGE

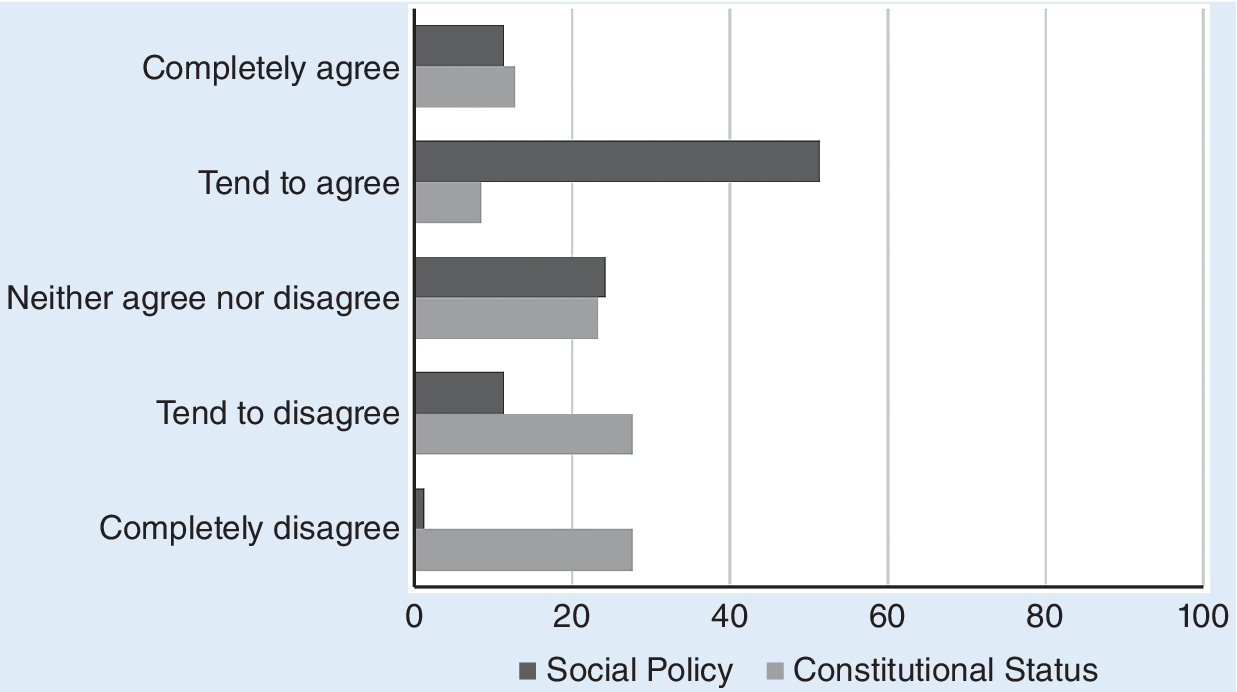

To test our remaining Hypotheses 2 and 3b, we considered whether participants reported any change in their views as a result of their discussions with other mini-public members. Aligned with our expectations, figure 3 shows that a majority of participants (63%) in the social-policy mini-public agreed that their views had changed as a result of the deliberative process. In the mini-public on constitutional status, a majority (55%) disagreed—with an even split between those tending to disagree and those completely disagreeing that they had changed their mind as a result of deliberation. A Mann-Witney U test shows that the differences between the two mini-publics in self-reported opinion change are statistically significant, providing evidence in line with Hypothesis 2.Footnote 10

Figure 3 Extent to Which Participants Agreed or Disagreed That They Changed Their Views as a Result of Deliberation (%)

There also are notable differences at the individual level. Nationalist participants and those identifying as neither nationalist nor unionist reported high levels of opinion change in the mini-public dealing with an ethnically contentious issue: 70% and 67%, respectively, agreed that they had changed their mind as a result of deliberation. In the mini-public dealing with an ethnically noncontentious issue, none of the nationalist participants agreed with the statement, along with 25% of those who identified as neither. These differences in perceived deliberative quality between the two mini-publics are statistically significant, providing only partial support for Hypothesis 3b (i.e., among nationalist participants).Footnote 11 Among unionist participants, there were no significant differences in the levels of self-reported opinion change between the two types of mini-public.Footnote 12 For context, a relatively small percentage of unionist participants in each mini-public agreed that they had changed their mind: 25% in the ethnically contentious mini-public and 40% in the ethnically noncontentious mini-public. In other words, among nationalists, unionists, and those identifying as neither, only a minority of participants in each group reported changing their mind in the ethnically contentious mini-public. However, in the ethnically noncontentious mini-public, majorities of nationalists and those who identified as neither reported changing their mind (and only a minority of unionists did so).Footnote 13

CONCLUSION

Our quasi-experimental study leverages the occurrence of two real-world mini-publics (mostly similar except for the topic covered) to provide evidence that mini-publics can function well from a deliberative perspective in deeply divided settings—even on issues that are ethnically contentious. Echoing Caluwaerts and Reuchamps (Reference Caluwaerts and Reuchamps2014), our findings suggest that neither deeply divided contexts nor polarizing issues present inherent obstacles to the successful operation of mini-publics, as indicated by participants’ evaluations of deliberative quality. Indeed, these evaluations were broadly positive in both mini-publics studied—and especially positive in the mini-public that considered an ethnically contentious issue. Of course, this finding is based on the participants’ subjective responses; it is possible that the objective quality of deliberation was broadly similar across the two mini-publics. However, perhaps participants in the mini-public discussing Northern Ireland’s future constitutional status generally were more surprised by the extent to which they felt comfortable expressing their opinions and by the level of respect shown during the discussions. This experience may have contrasted with participants’ experience of constitutional debates portrayed in the media involving either politicians or studio audiences. Therefore, even if the prospects for opinion change appear limited—which does not pose a problem from a deliberative perspective (Niemeyer and Dryzek Reference Niemeyer and Dryzek2007)—mini-publics nevertheless may provide a constructive space for confronting ethnically contentious issues that otherwise would be lacking.

…our findings suggest that neither deeply divided contexts nor polarizing issues present inherent obstacles to the successful operation of mini-publics, as indicated by participants’ evaluations of deliberative quality.

Our study has several important caveats. First and foremost, neither of the mini-publics considered possessed formal decision-making authority. The collective attitudes of participants from each mini-public were summarized and made available to relevant government officials for their consideration. Second, however, the relatively low stakes involved may have shaped the deliberative character of the mini-publics in a largely positive direction. With higher stakes, it is possible that the findings could have been negatively influenced. Third, as a related point, neither mini-public was set up by a statutory body. Those organized on an official basis in deeply divided places, rather than by nongovernmental organizations or as part of academic projects, may have a clearer path to a direct policy impact. However, particular care will be needed to promote deliberative integrity across all stages of their design, including the way that the issue is framed initially (Curato et al. Reference Curato, Farrell, Geissel, Grönlund, Mockler, Pilet, Renwick, Rose, Setälä and Suiter2021).

Nevertheless, more directly experimental research is required to systematically compare the design and effects of mini-publics in a wide range of contexts. However, this article challenges the basic idea that these processes are doomed to descend into acrimony in deeply divided places, even when ethnically contentious issues are considered. The dominance of the ethno-national dimension in Northern Ireland typically may render the region “a place apart,” but recent developments have exposed identity-based divisions elsewhere in the United Kingdom—including the issues of Brexit and Scottish independence. Therefore, we suggest that those places that are deeply divided along ethnic lines nevertheless can provide relevant lessons for comparatively stable polities that become polarized in other ways.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Versions of this article were presented at the International Political Studies Association’s 2019 “Conference on Diversity and Democratic Governance in Sarajevo, Bosnia, and Herzegovina” and at the 2019 Annual Meeting of the Political Studies Association of Ireland in Maynooth. This research was supported by the Economic and Social Research Council of the United Kingdom (Grant No. ES/R000417/1). We thank Tim Hughes, Rebekah McCabe, and Kaela Scott at Involve for facilitating our research collaboration with the Citizens’ Assembly for Northern Ireland. We also thank the reviewers for their helpful comments. Any errors, of course, are our own.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Research documentation and data that support the findings of this study are openly available at the PS: Political Science & Politics Harvard Dataverse at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/KSQCEQ.

Supplementary Material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/S1049096523000409.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare that there are no ethical issues or conflicts of interest in this research.