Published online by Cambridge University Press: 25 November 2022

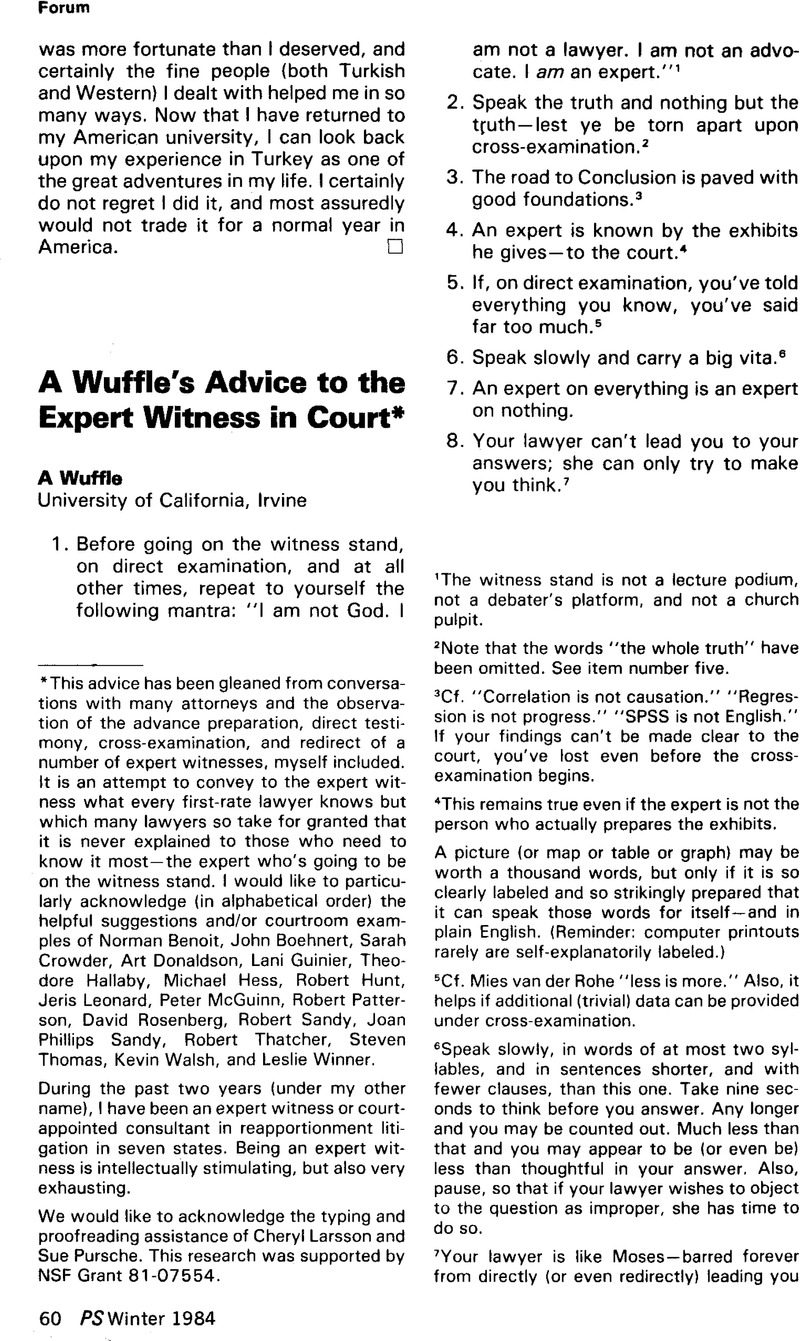

This advice has been gleaned from conversations with many attorneys and the observation of the advance preparation, direct testimony, cross-examination, and redirect of a number of expert witnesses, myself included. It is an attempt to convey to the expert witness what every first-rate lawyer knows but which many lawyers so take for granted that it is never explained to those who need to know it most—the expert who's going to be on the witness stand. I would like to particularly acknowledge (in alphabetical order) the helpful suggestions and/or courtroom examples of Norman Benoit, John Boehnert, Sarah Crowder, Art Donaldson, Lani Guinier, Theodore Hallaby, Michael Hess, Robert Hunt, Jeris Leonard, Peter McGuinn, Robert Patterson, David Rosenberg, Robert Sandy, Joan Phillips Sandy, Robert Thatcher, Steven Thomas, Kevin Walsh, and Leslie Winner.

During the past two years (under my other name), I have been an expert witness or court-appointed consultant in reapportionment litigation in seven states. Being an expert witness is intellectually stimulating, but also very exhausting.

We would like to acknowledge the typing and proofreading assistance of Cheryl Larsson and Sue Pursche. This research was supported by NSF Grant 81–07554.

1 The witness stand is not a lecture podium, not a debater's platform, and not a church pulpit.

2 Note that the words “the whole truth” have been omitted. See item number five.

3 Cf. “Correlation is not causation.” “Regression is not progress.” “SPSS is not English.” If your findings can't be made clear to the court, you've lost even before the cross-examination begins.

4 This remains true even if the expert is not the person who actually prepares the exhibits.

A picture (or map or table or graph) may be worth a thousand words, but only if it is so clearly labeled and so strikingly prepared that it can speak those words for itself—and in plain English. (Reminder: computer printouts rarely are self-explanatorily labeled.)

5 Cf. Mies van der Rohe “less is more.” Also, it helps if additional (trivial) data can be provided under cross-examination.

6 Speak slowly, in words of at most two syllables, and in sentences shorter, and with fewer clauses, than this one. Take nine seconds to think before you answer. Any longer and you may be counted out. Much less than that and you may appear to be (or even be) less than thoughtful in your answer. Also, pause, so that if your lawyer wishes to object to the question as improper, she has time to do so.

7 Your lawyer is like Moses—barred forever from directly (or even redirectly) leading you into the promised land. She can prepare you to anticipate questions, but she can't put words in your mouth.

8 Often the cross-examining attorney will ask you questions about matters peripheral to your direct testimony, hoping to get you into an argument or to get you to appear evasive. Don't bite. If the question is improper, your attorney will object. Otherwise just answer the question, simply and nonargumentatively.

9 The discovery deadline determines when each side must make available to the other side witness lists and exhibition lists.

10 “Expert is expert and lawyer is lawyer and frequently the two shall meet.

11 “It may be obvious to you, it may be obvious to the attorneys, it may even be obvious to the judge; but the court recorder's transcript won't show it (for the appellate court to acknowledge) if you don't say it for the record.

12 As told to A Wuffle by his mother.

13 Confucius say: expert witness like a rubber tire, either one big puncture or lots of little ones and credibility shot. Most punctures, however, can be repaired (on redirect) and the tire back almost as good as new.

14 Among the words most likely to give a cross-examining attorney acid indigestion are these: “As I testified previously.”

15 The less you say on cross-examination the less you'll live to regret. The two most beautiful words your attorney can hear on response to cross-examination are “yes” and “no.” Almost as good is “I don't know.” If a question can't be answered with a yes or no, then either say you can't answer the question as it is presently worded with a yes or no and ask for it to be restated, or ask for the opportunity to explain your answer.