Patients with personality disorder place high demands on health and social services, with borderline and schizotypal personality disorders being associated with extensive use of mental health services (Reference Bender, Dolan and SkodolBender et al, 2001). In Scotland, individuals with personality disorder account for almost 5% of all psychiatric admissions in the <65 age group (ISD Scotland, 2001). This study examines the extent of in-patient psychiatric treatment in the management of individuals with personality disorder in a Scottish general adult psychiatry service.

Method

Ailsa Hospital provides psychiatric in-patient care (two 29-bedded wards) for the general adult psychiatry service for the southern half of the Ayrshire and Arran Health Board area. The hospital also contains the intensive psychiatric care unit (7 beds), the addictions dual diagnosis in-patient unit (12 beds) and two continuing care wards (14 and 12 beds, respectively) for the whole of Ayrshire and Arran.

A retrospective survey of case-notes was carried out for all patients from the southern half of Ayrshire with personality disorder (ICD code F60) admitted to the hospital in 2001. Patients were identified using the computerised patient administration system (COMPAS), which can provide diagnostic information (ICD-10 (World Health Organization, 1992) admission and discharge clinical diagnoses) in addition to information on duration and location of in-patient stay. A subgroup of patients with longer duration of admission (5 weeks or more in total) in 2001 was identified. Records of this subgroup’s in-patient care in the preceding 4 years were then examined to observe the pattern of admission over a longer period of time.

Data were collected on each patient’s diagnosis (personality disorder and other psychiatric illness), associated alcohol and substance misuse for admissions in 2001, and on the number and length of in-patient admissions over the 5-year period for those in the subgroup.

Results

Eight hundred and forty-four patients from the southern half of Ayrshire were admitted to the general psychiatry wards at Ailsa Hospital over the year 2001. Of these, 62 (7.35%) were given a diagnosis of personality disorder. The male:female ratio was 24:38. More admissions were seen in the younger age group, 16-39 years, n=45, than in the older age group, 40-65 years, n=17.

Diagnostic categories

Thirty-nine (63%) had a primary diagnosis of personality disorder. Nineteen (30%) had an additional diagnosis of psychiatric disorder (depressive episode; acute stress reaction; schizophrenia; mild mental retardation). Twelve (19.3%) had a diagnosis of alcohol or substance misuse, and 3 (4.8%) had both a psychiatric disorder and a disorder due to alcohol or substance misuse in addition to personality disorder.

Personality disorder subtypes were diagnosed as follows: Emotionally unstable 32 (51.6%); Unspecified 16 (25.8%); Dissocial 8 (12.9%); Anxious [avoidant] 3 (4.8%); Dependent, Histrionic and Other specific personality disorder 1 (1.6%) each.

Pattern of admission

In 2001, 62 patients spent 497 weeks in in-patient care. A subgroup of 25 patients was identified with a total stay in excess of 5 weeks in this year. To further examine the longer-term pattern of in-patient treatment, this subgroup was considered on the assumption that their problems were more severe. Sixteen (24%) had a diagnosis of emotionally unstable personality disorder. In 2001, this subgroup had an average in-patient stay of 13.24 weeks, in contrast to the average stay of 8.02 weeks for the whole group.

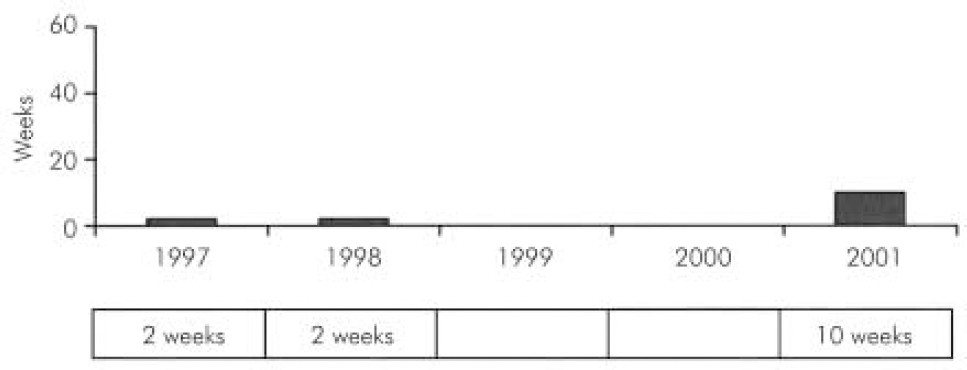

When the earlier years’ admission patterns were examined, the subgroup of 25 patients had been admitted for a total of 647 weeks between 1997-2000 (average 6.47 weeks per patient per year). Within the subgroup of 25 patients who were admitted for 5 weeks or longer in 2001, two patterns of admission in earlier years were noted. Some patients were admitted for the first time in 2001. The first admission pattern consisted of patients who had comparatively few, brief admissions in the earlier years, e.g. Patient 10 (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Patient 10.

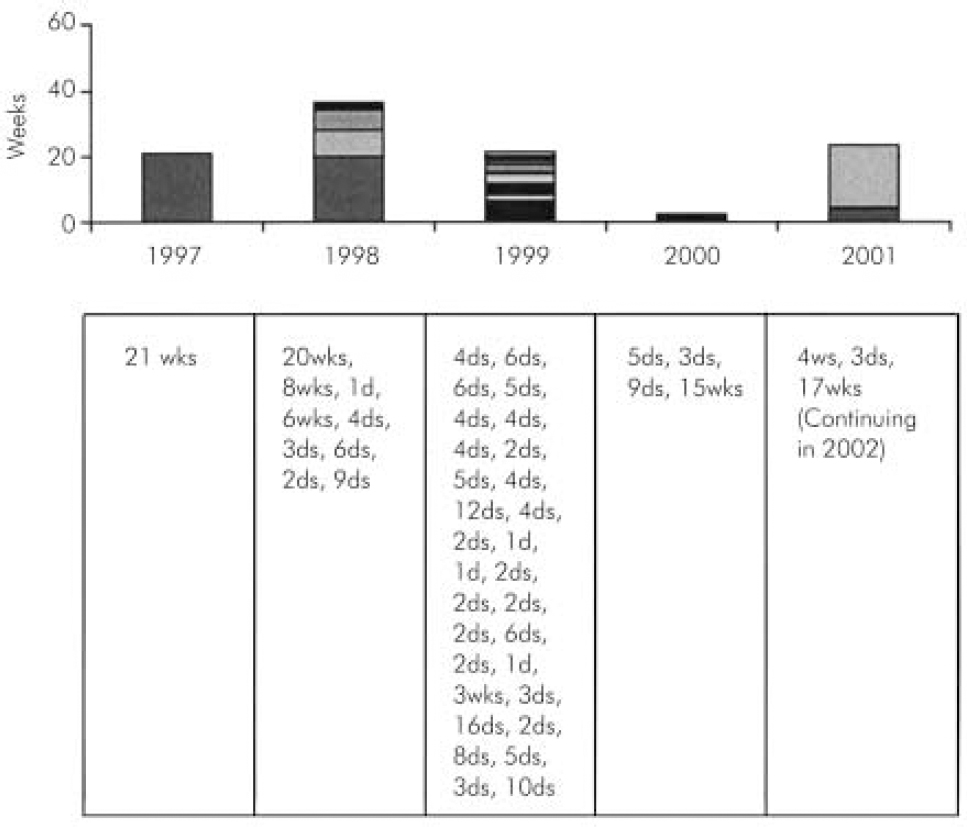

The second pattern of admission consisted of patients who had numerous admissions and a total of many weeks per year as an in-patient, e.g. Patient 21 (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Patient 21.

Discussion

Personality disorder accounted for just over 7% of all admissions to acute general adult psychiatric beds in our study. The majority of people with personality disorders admitted are female, under 40 years old and of the emotionally unstable type. Many of those with a diagnosis of personality disorder also have another diagnosed psychiatric disorder, or disorder resulting from misuse of alcohol or drugs. Looking at the pattern of admission for a subgroup of patients who were admitted for over 5 weeks in 2001, we formed an impression, untested by statistical analysis, of two extremes of contact: little or none at one extreme and frequent and/or lengthy admissions at the other.

The admission rate for personality disorder in Ailsa Hospital is slightly higher than that quoted for Scotland as a whole for the year 2000-2001 (ISD Scotland, 2001). The Scottish data includes admissions for alcohol and substance abuse and pre-senile dementia in the denominator, some of which would be dealt with by sub-specialist services in Ayrshire. The Scottish data also reflects the fact that community-based psychiatric services are not fully developed in all health board areas. The community mental health services in Ayrshire are comparatively well developed. The preponderance of females admitted in our study was more marked in the Scottish data as a whole, male:female=367:675 for admissions aged <65 years.

It could be argued that the rates for our study and for Scotland as a whole are not as high as have been found elsewhere. Studies of personality disorder tend to use research-oriented diagnostic criteria, which have been found to increase the likelihood of clinicians making a diagnosis of personality disorder when compared with the usual clinical interview (Reference Zimmerman and MattiaZimmerman & Mattia, 1999). While many studies of the prevalence of personality disorders in psychiatric in-patients using standardised assessment instruments produce results in the region of 50% or more, studies of administrative data show a prevalence ranging between 5-12% (Department of Health, 1995; Reference Olfsun and MechanicOlfsun & Mechanic, 1996). The rates for our study and for Scotland as a whole are derived from clinical discharge diagnoses.

Most of the patients with personality disorder in our study were in the younger age group. This may fit with the belief that patients mature and their personality traits become less troublesome with time. Recent work in this area by Zanarini et al (Reference Zanarini, Frankenburg and Hennen2003) showed a high rate of remission, but admitted that the patients in their study were highly disturbed and highly treated, and that they could not determine if the remission was a result of treatment or something else. The predominance of the emotionally unstable personality disorder in our in-patient group is in keeping with findings of earlier work (Reference de Girolamo, Dotto, Gelder, Lopez-Ibor and Andreasende Girolamo & Dotto, 2000).

Limitations of our study include the small numbers of patients and the retrospective method, dependent on accurate case-note recording and accurate clinical diagnoses. We did not attempt to validate the diagnoses. We did not carry out a statistical analysis of clustering of admission patterns in earlier years for the subgroup with longer stays in 2001. We cannot exclude the possibility that Ayrshire patients with personality disorder were admitted to psychiatric hospitals elsewhere. However, bed pressures in the West of Scotland as a whole tend to result in Ayrshire’s import rather than export of admissions. Our study did not examine treatment or its outcome. The coexistence of personality disorder with Axis I disorders has implications for how those psychiatric disorders can be managed. Much has been written about treatment of personality disorder in specialist units, but it remains to be seen if these levels of treatment can be applied in secondary care settings with similar effect.

Acknowledgements

Dr J. A. Flowerdew helped to devise the original idea for this survey. Thanks are owed to him and to the staff in medical records and the clinical effectiveness department at Ailsa Hospital.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.