Evidence-based guidelines (EBGs) are used increasingly in routine clinical practice but in comparison with general practice, they are uncommon in psychiatry. With the advent of the National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE), the use of guidelines is likely to become more widespread as more reviews are disseminated, but little is known about attitudes of psychiatrists to their use.

Guidelines primarily aim to make care more consistent and efficient and reduce inappropriate variations in practice. Clinical practice guidelines can be defined as ‘systematically developed statements to assist practitioner and patient decisions about appropriate health care for specific clinical circumstances’ (Reference Field and LohrInstitute of Medicine, 1992). EBGs are a specific adaptation based on critical appraisal of scientific evidence and they clarify which interventions are of proven benefit and document the quality of the supporting data (Reference Woolf, Grol and HutchinsonWoolf et al, 1999). The EBG development process should be explicit, clearly stating how evidence was identified and selected. The development group should be representative of all those to whom the EBGs will be relevant. Peer review should be included and a review date explicitly stated in the guideline (Reference Marriott and PalmerMarriott & Palmer, 1998).

Psychiatrists' attitudes to evidence-based psychiatry have been studied by Carey & Hall (Reference Carey and Hall1999): clinicians overwhelmingly (>90%) felt it was ‘useful’ in clinical practice, but a similar number felt this to be true of clinical intuition and the opinion of colleagues. Only 60% felt more use of evidence-based practice was attainable. Watkins et al (Reference Watkins, Harvey and Langley1999) explored how general practitioners (GPs) gain access to and use guidelines. They concluded guidelines were perceived as a useful method of accessing specialist information; positive attitudes towards them were more common among younger GPs. Siriwardena (Reference Siriwardena1995) found that GPs were generally in favour of clinical guidelines and believed them effective in improving patient care. A positive response was associated with GPs who had previously contributed to inhouse guidelines or participated in audit. Our study examined psychiatrists' attitudes to EBGs and made comparisons with previous research in primary care. It was hypothesised that psychiatrists who qualified more recently (less than 8 years since qualification to reflect the ‘era’ of evidence-based medicine) would have more positive attitudes owing to more training in evidence-based medicine and familiarity with guidelines.

Method

A postal questionnaire was sent to psychiatrists (consultant, specialist registrar and non-consultant career grades listed as working in general adult speciality; n=105) in one large specialist mental health care trust (Avon and Western Wiltshire Mental Health Partnership NHS Trust; population served 1.2 million). A second copy of the questionnaire was sent to non-respondents after 6 weeks and followed up with a telephone reminder if not returned subsequently. The characteristics of respondents can be seen in Table 1.

Table 1. Characteristics of respondents

| Percentage of respondents | n | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 65 | 62 |

| Female | 34 | 33 |

| Data missing | 1 | 1 |

| Age | ||

| 25-34 | 20 | 19 |

| 35-44 | 47 | 46 |

| 45-54 | 28 | 27 |

| >55 | 4 | 3 |

| Data missing | 1 | 1 |

| Status | ||

| Consultant | 41 | 39 |

| Specialist registrar | 30 | 29 |

| Non-consultant career grade | 28 | 27 |

| Data missing | 1 | 1 |

| Specialty | ||

| General adult | 50 | 48 |

| General adult or dual accreditation | 35 | 34 |

| Other | 14 | 13 |

| Data missing | 1 | 1 |

The questionnaire consisted of 18 attitude statements on clinical guidelines adapted from a questionnaire used to assess attitudes to guidelines in general practice (Reference SiriwardenaSiriwardena, 1995). The original was developed following a qualitative pilot study (literature search and semi-structured interviews with GPs), which identified 10 ‘areas of concern’ as being relevant to the use of guidelines. Statements particularly related to primary care (e.g. performance-related pay) were replaced by alternatives (e.g. how guidelines relate to research). Siriwardena surveyed 213 GPs whose mean statement scores were used as a comparison group for the purpose of our study. As respondents are more likely to reply in the affirmative, we employed a balanced questionnaire using (randomly ordered) paired statements expressing opposite attitudes. These are listed by category in Table 2. A Likert-type scale was used, with five response codes ranging from strongly agree (1) to strongly disagree (5) for each statement. For analysis, scores were combined for agreement (1+2) and disagreement (4+5). Mean scores were calculated after reversing the scores for positive statements; thus a higher score always signified a more positive attitude to guidelines. Mean scores for paired statements in each category were added; a score of more than 6.0 indicated a positive attitude, less than 6.0 indicated a negative attitude and 6.0 indicated equivocation. Completed questionnaires were analysed using SPSS for Windows, Version 8.0 (SPSS, 1997).

Table 2. Responses to paired statements in questionnaire on attitudes to clinical guidelines

| Psychiatrists | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Statements about evidence-based guidelines | % agree (strongly) | Mean scores* | Sum of means |

| Can improve patient care | |||

| Using well-constructed guidelines will improve patient care | 82.3 | 4.01 | 7.67 |

| Guidelines would not improve the care I give to patients | 14.6 | 3.66 | |

| Do not diminish clinical freedom | |||

| I can exercise clinical judgement within guidelines | 85.7 | 4.16 | 7.22 |

| Guidelines will diminish a psychiatrist's clinical freedom | 34.0 | 3.06 | |

| Do not stifle innovation | |||

| Guidelines help psychiatrists to work in the same way | 73.6 | 3.80 | 6.86 |

| Guidelines stifle innovation | 29.7 | 3.06 | |

| Can be applied flexibly to individual patients | |||

| Guidelines can be used flexibly to suit needs of individual patients | 85.7 | 4.14 | 7.95 |

| Patients are too different for guidelines to be of any use | 9.9 | 3.81 | |

| Help to avoid litigation | |||

| If I followed accepted guidelines I am less likely to be sued | 64.9 | 3.67 | 7.08 |

| Adopting guidelines will increase the risk of litigation | 22.0 | 3.41 | |

| Should be sensitive to local needs | |||

| Guidelines should be based on what actually happens in clinical practice | 35.5 | 3.04 | 6.52 |

| Psychiatrists shouldn't bother to develop local guidelines when national guidelines exist | 21.1 | 3.48 | |

| Should only be based on scientific evidence | |||

| Good practice is not always scientific | 73.6 | 3.97 | 7.01 |

| We should base guidelines only on what has been scientifically proven | 33.7 | 3.04 | |

| Are helpful to my own clinical practice | |||

| I find it helpful to follow accepted guidelines | 70.0 | 3.77 | 6.44 |

| I didn't become a psychiatrist to practise ‘cookbook’ medicine | 42.7 | 2.67 | |

| Can be based on sufficient evidence in psychiatry | |||

| Guidelines help stimulate research into effectiveness of treatments and therefore the development of knowledge | 63.8 | 3.64 | 7.00 |

| There is insufficient available evidence on treatment efficacy in psychiatry upon which to develop valid guidelines | 27.0 | 3.36 | |

Results

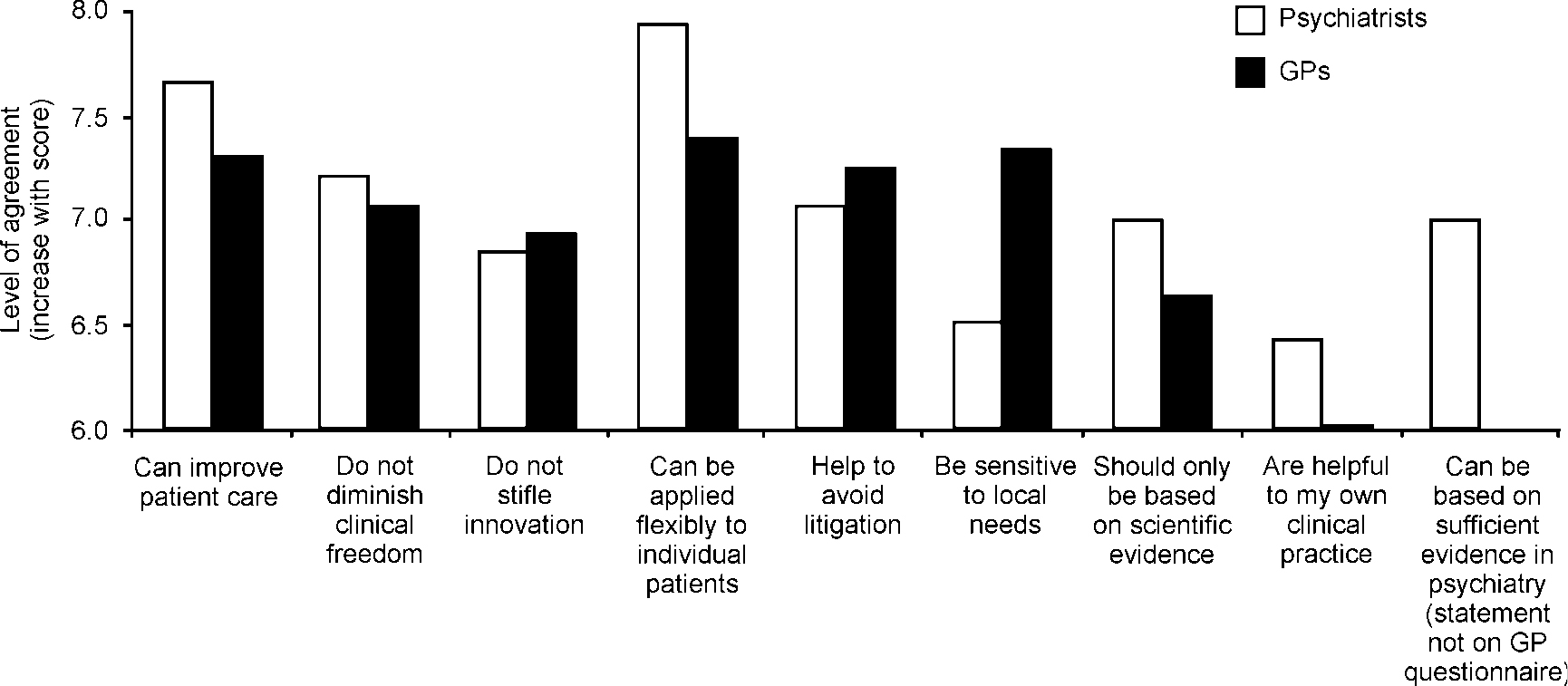

Of the 105 questionnaires sent to psychiatrists, 96 were returned completed — a 91% response rate. The characteristics of respondents are shown in Table 1. The mean years of psychiatric experience was 12.7 (s.d. ± 7.2). The responses to the 18 attitude statements are displayed in pairs in Table 2. Response scores indicated a positive attitude to guidelines in 13 of the 18 statements, a negative attitude in 1 and equivocation in 4. The majority (82.3%) believed that guidelines were effective in improving patient care. There was also strong agreement that clinical judgement could be exercised within guidelines (85.7%), guidelines could be used flexibly to suit the needs of individual patients (85.7%) and respondents found guidelines helpful to follow (70%). There were trends for psychiatrists to be more positive than GPs in all these areas (82% v. 69%, 85% v. 76%, 85% v. 74% and 70% v. 57%, respectively) (see Fig. 1; GP percentage scores and means, from Reference SiriwardenaSiriwardena, 1995). More recently-qualified psychiatrists did not exhibit significantly more favourable attitudes on any statements, and further subgroup analysis (on variables gender, specialty and grade) revealed no significant differences. The two main categories in which GPs scored more positively than psychiatrists were believing guidelines were helpful to avoid litigation and that guidelines should be sensitive to local needs.

Fig 1. Comparison of psychiatrist and general practitioner (GP) mean scores (GP data from Reference SiriwardenaSiriwardena, 1995).

Discussion

The excellent response rate (91%) indicates that our sample is highly representative of psychiatrists within the trust. The study was not sufficiently powered (small sample size) to detect any relevant differences between psychiatrist groups. The results suggest psychiatrists have positive attitudes towards EBGs and in most categories appear more favourably disposed to them than GPs. However, Siriwardena surveyed a population in a different region over 5 years previously. His survey did not discriminate between locally-developed guidelines (often ‘owned’ by those involved in development) and expert, systematically-based guidelines (potentially viewed as imposition). Similarly, our questionnaire did not include a definition for EBGs or examine how guidelines are formulated. The culture of using guidelines in psychiatry and primary care is also likely to be different, with psychiatrists having limited personal use compared with their GP colleagues. Positive views from psychiatrists may, therefore, reflect an acceptance viewed from a distance rather than from proven experience. Only 57% of GPs agreed it was helpful to follow guidelines and the overall category score (‘helpful to my own clinical practice’) was equivocal.

The increasing profile of guidelines within psychiatry is likely to be controversial. The future demonstration of clinical competence as part of the revalidation process (which the clinician may have to prove) could include examination of how an individual's practice conforms to established guidelines. Our results suggest psychiatrists will not see EBGs as a threat, a majority believing they can improve patient care and retain flexibility for individual patients while not diminishing clinical freedom. However, a significant proportion (43%) remained concerned about ‘cookbook’ psychiatry arising from the widespread introduction of EBGs, which may be a barrier to their clinical use. It will be important to harness favourable attitudes to encourage psychiatrists to develop EBGs through evidence-based approaches and local clinical audit. (GPs clearly support guidelines being sensitive to the needs of local practice.) Within psychiatry, critics of EBGs often state that there is insufficient evidence on treatment efficacy upon which to develop valid guidelines. In this survey, 73% of psychiatrists disagree.

In primary care, GPs frequently fail to follow systematic guidelines (Reference Moher and JohnsonMoher & Johnson, 1994) and there are notable failures in their impact on patient treatment outcomes (Reference Thompson, Kinmonth and StevensThompson et al, 2000). In spite of positive attitudes, there is no reason to expect better results in psychiatry. The challenge for researchers will be to demonstrate successful implementation strategies (of which EBGs will be only one component of multifaceted interventions) that have clear efficacy in treatment outcomes and which retain the favourable attitudes of those who use them.

Declaration of interest

None.

Acknowledgement

We thank all the psychiatrists who participated.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.