One of the consequences of the Calman reforms of postgraduate training for child and adolescent psychiatrists is shorter training (Department of Health, 1993). Of central importance to effective training is the range of clinical experience. The specific training requirements are set out in the Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Specialist Advisory Sub-Committee (CAPSAC) advisory papers, which specify the number of cases open at one time to a trainee and the total number of cases seen in a year. The CAPSAC also expects trainees to have ‘experience in developing skills in the assessment, formulation and treatment of all the main psychiatric disorders encountered in children and adolescents’ (Royal College of Psychiatrists' Higher Specialist Training Committee, 1999: p. 6). To ensure that training needs are met requires careful planning and ongoing monitoring.

An audit of specialist registrars' case-load and case mix has been undertaken since 1996 in the Mersey deanery. The training scheme in child and adolescent psychiatry includes placements in community out-patient settings, an adolescent in-patient unit and an in-patient unit for the under 14-year-olds. There is also a day patient unit and specialised placements in learning disability and clinical research. The scheme as a whole therefore offers a wide range of training opportunities. Although case-loads are monitored individually in placements, the case-load and case mix can vary widely with the different experiences available in the various training posts, especially in the more specialised placements. The trainee group therefore felt that it was important to monitor the scheme as a whole.

The findings from this audit have been presented annually to trainers and trainees in various forums. These include the annual Mersey Regional Group of Child and Adolescent Psychiatrists' research and audit meeting, the trainer/trainee meetings and the specialist registrar teaching programme.

The study

Each trainee kept an agreed minimum set of data on his or her own cases. At the end of each placement, data were collected and analysed using a computerised spreadsheet. The results of the audit were presented to trainers and trainees. Problem areas were identified and possible solutions discussed. A handout was prepared for each audit and distributed to trainers and trainees. Individual trainees and trainers could then use the information to help plan the trainee's case-load for the next year. Case-load and case mix were re-audited annually and problem areas reviewed.

Data collected included:

-

(a) Numbers of cases open on 31 January each year.

-

(b) Total number of cases seen in a year's placement (from beginning of April to end of March).

-

(c) Gender of cases.

-

(d) Age of cases. This was divided into four age groups: 0-5 years, 6-11 years, 12-16 years and 17 years and over.

-

(e) Primary diagnosis: ICD-10 (World Health Organization, 1992) diagnoses were used and then grouped using a list of diagnoses derived from a variety of logbooks used by other training schemes.

Findings

Three trainees took part in the audit in the year ending 31 March 1997, four the next year, eight the following year and seven in the year ending 31 March 2000. Overall 42% of trainees were male, 58% female, 33% were flexible trainees and one trainee was completing a dual training in child psychiatry and learning disability. For the purpose of the audit, figures for flexible trainees were adjusted to the full-time equivalent. A total of 60% of trainees on the scheme took part in the audit in the first year, 67% the next year, 89% the following year and 100% in the year ending 31 March 2000. Of the trainees who did not take part in the audit, one was a flexible trainee on maternity leave, one was a trainee who had gained his Certificate of Completion of Specialist Training (CCST) and was applying for consultant posts and the other two were flexible trainees.

Annual case-load

Annual case-loads were highest in the first year of the audit, with two of the three trainees having annual case-loads above the CAPSAC guidelines of 50-75 (highest=109) (Royal College of Psychiatrists Higher Specialist Training Committee, 1999). On reviewing the case mix, the reason for this was the assessment of large numbers of cases of deliberate self-harm (DSH). Since then, trainees have not been expected to assess all cases of DSH and most trainees have achieved annual case-loads that fall within the CAPSAC guidelines. Recently, high annual case-loads have been associated with seeing a high percentage of cases of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). The only trainee with a low annual case-load was doing a specialised learning disability placement, where much of the work was done by consultation.

Point case-load

Point case-loads varied widely, with a range of 9-52. (The CAPSAC guidelines advise a point case-load of 20-30 cases.) Certain jobs were always associated with low point case-loads: the two in-patient posts and the research post. Trainees who had recently started on the scheme had low case-loads. High case-loads were associated with particular posts and appeared to be related to the types of cases seen, especially where a high percentage of cases of ADHD was seen (see case mix by diagnosis, below).

Case mix by diagnosis

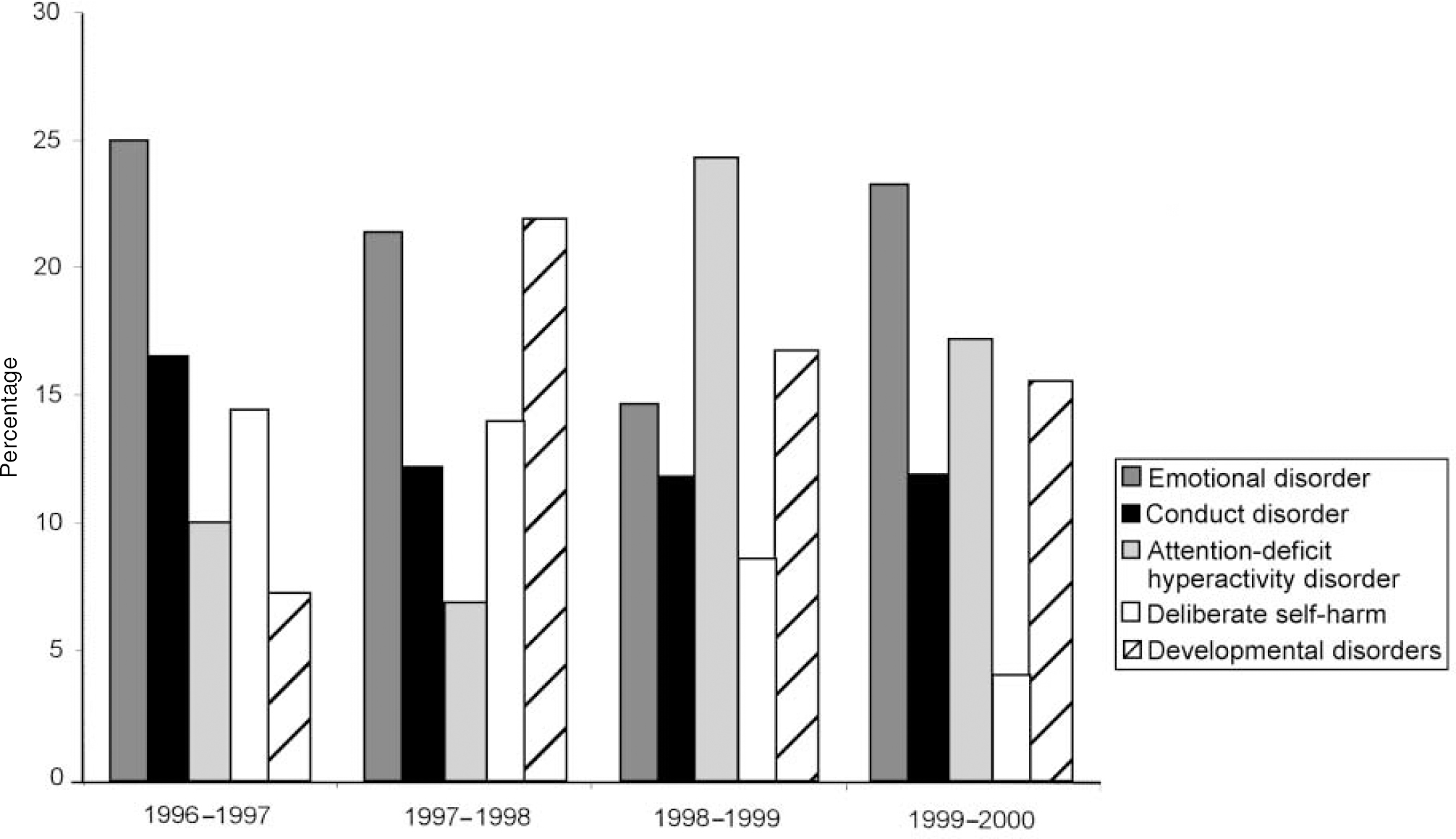

In the first 2 years of the audit, trainees saw large numbers of cases of DSH. Following the initial audit cycle, changes were made to the scheme and there has been a trend away from trainees seeing an excess number of DSH cases (Fig. 1). Some trainees now lack experience of DSH assessments. Other diagnostic groups are becoming more prominent, in particular ADHD (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Percentage of cases seen by trainees: the main diagnostic groups.

Case mix by age

As expected, most cases seen fell into the 5-11-year and 12-16-year age groups. Most trainees had seen some children under the age of 5 years but few had seen cases in the 17 years and over group.

Case mix by gender

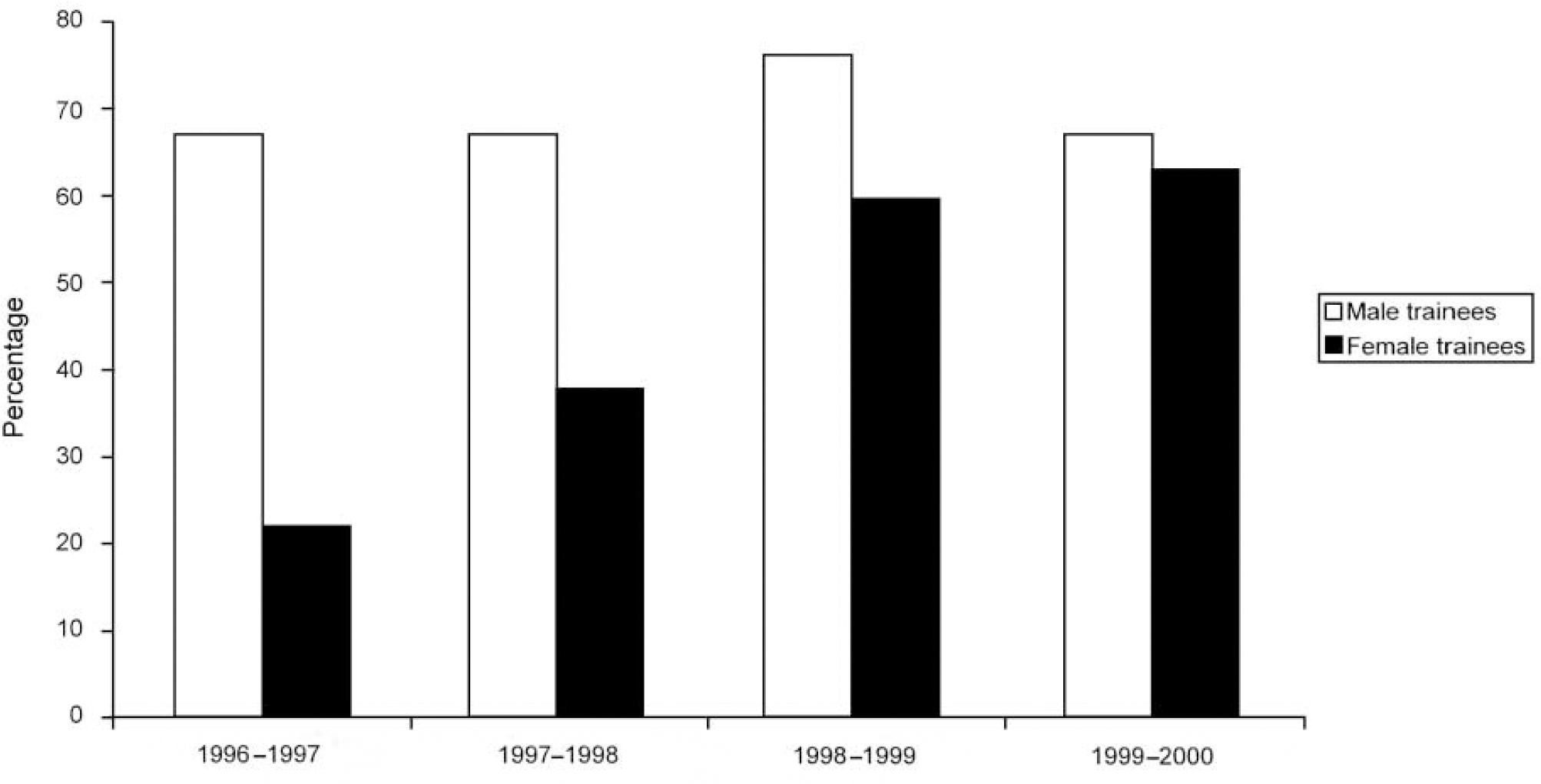

In the first 2 years of the audit, female trainees were mainly seeing girls and male trainees were mainly seeing boys (Fig. 2). It was felt that the trainees' case-loads should reflect that of the consultants, who were seeing more boys. The issue was tackled following the audit, and in the subsequent 2 years nearly every trainee was seeing more boys. (The only trainee who was seeing more girls was working on the eating disorders unit.)

Fig. 2. Boys as a percentage of case-load.

Discussion

The audit has allowed the scheme to modify the overall training on offer. For example, DSH assessments were seen previously as being the trainees' responsibility. Changes in working patterns in placements mean that this is no longer the case.

Trainees used audit findings and their own personal data to help plan their clinical training. A selection of clinical cases helps to ensure that clinical and non-clinical training needs are met in the reduced time available for specialist registrar training. It can be difficult to balance training needs with the clinical demands in placements. The information from the audit helped trainees to set boundaries and say ‘no’ to certain types of cases that were meeting clinical, rather than training, needs.

Some trainees had high point and annual case-loads. This was discussed at length at the audit presentations. It was felt that high case-loads were acceptable if the trainee concerned felt this to be a useful training experience and if it did not prevent the trainee from meeting other essential training requirements. Numbers of cases seen does not accurately reflect the workload involved. Some cases, for example routine ADHD reviews or one-off assessments, will take up relatively little clinical time. Smart and Cottrell surveyed training experiences in child and adolescent psychiatry and found a wide variation in point case-loads (Reference Smart and CottrellSmart & Cottrell, 2000).

Some trainees expressed concerns about revealing details regarding their personal workload because it was difficult to completely anonymise the data. However, the percentage of trainees taking part in the audit increased each year, suggesting that trainees found the audit useful. Trainees not taking part in the audit included flexible trainees and one trainee who had gained his CCST. There should be caution in interpreting the results as being representative of all the trainees on the Mersey scheme or trainees elsewhere in the country.

As the role and working practices of child psychiatrists continue to change and develop, it is likely that the training scheme and training opportunities will change too. We therefore think that it is important to continue to monitor and audit training. The case-load/case mix audit is an important part of this process.

Declaration of interest

None.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.