In patients who have been given a diagnosis of dementia, the issue of driving is of vital importance. For many people, being able to drive is crucial for their independence. In the UK the law requires anyone who has been given a diagnosis of dementia to inform the medical branch of the Driver and Vehicle Licensing Agency (DVLA; Driver and Vehicle Licensing Agency, 2004). Failure to do so can result in a fine of £1000 and will also be likely to invalidate insurance. Many drivers with early dementia will have their licence renewed by the DVLA, although other people may be deemed unsafe to drive. The evidence regarding the safety of driving in dementia suggests that people with dementia do have a higher risk of being involved in an accident (Reference CarrCarr, 1997), although this finding has not been universal (Reference Trobe, Waller and CookflannaganTrobe et al, 1996). Subcategorisation of drivers with dementia has shown patients to be at significantly increased risk only at the more severe end of the spectrum (Reference Dubinsky, Stein and LyonsDubinsky et al, 2000).

Professionals treating people with dementia should consider the issue of driving and are in a unique position to inform patients of their legal responsibilities. In the service in which the authors were working there was the perception that this issue might in some cases be unintentionally overlooked. This has the potential to leave issues of risk and safety unaddressed and also raises important legal considerations. We decided to perform an audit to investigate this in a day hospital specialising in the assessment and treatment of people with dementia.

Method

We considered the gold standard to be that the issue of driving is discussed with all patients given a diagnosis of dementia. Those who are still driving should be advised that they must inform the DVLA of their medical condition. Within a reasonable period, which we set as 1 month, patients should be interviewed again to ensure that they have acted on the advice given. In exceptional circumstances, where the patient has refused to inform the DVLA and continues to drive, the consultant psychiatrist should decide whether to inform the DVLA against the patient’s wishes, and this decision should be documented.

The notes of all patients attending the Elms Day Hospital in Enfield during January 2004 were thoroughly reviewed, looking for evidence that the issue of driving had been discussed. In cases where this had been documented, we looked for evidence of what advice had been given to the patient regarding informing the DVLA of his or her condition. We then assessed whether this advice had been followed up within 1 month.

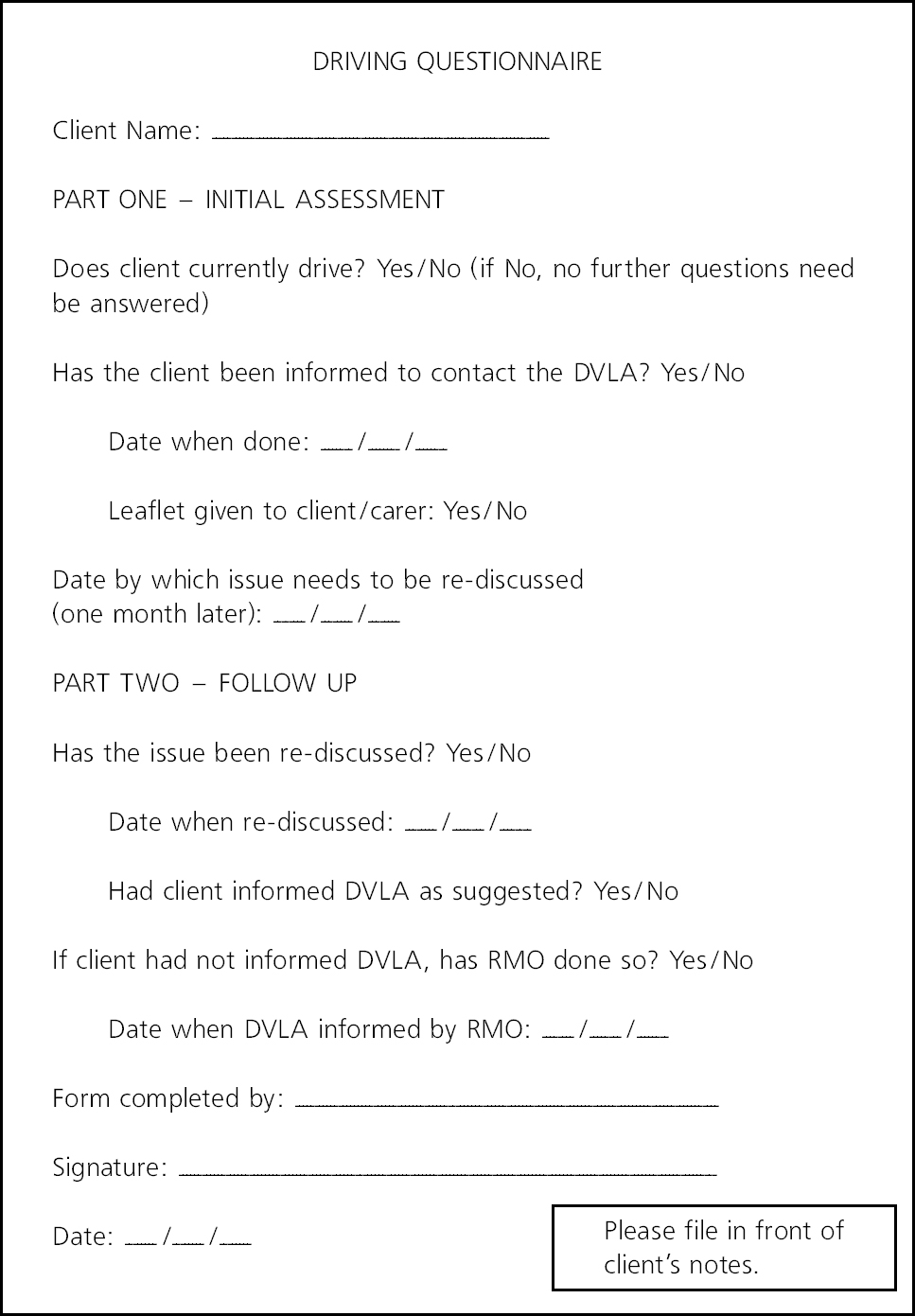

Following the evaluation of these results, we presented our findings to staff at the day hospital and then implemented an audit questionnaire for staff to use when admitting patients. This questionnaire was constructed after consultation with the various professionals working within the hospital, so that it was quick and easy to complete. Any member of the multidisciplinary team could complete the questionnaire, which would then be signed and inserted into the front of the patient’s medical notes (Fig. 1). It was also suggested that patients who had been advised to contact the DVLA should be given a factsheet detailing the issues. The leaflet designed by the Alzheimer’s Society was used (Alzheimer’s Society, 2000). We repeated the audit in November 2004; all new patients admitted since April 2004 were included, representing a 6-month period. The same gold standard was applied to these patients.

Results

Forty-four patients were attending the Elms Day Hospital during January 2004 when the first cycle of audit was undertaken. Of these patients, 41 had a diagnosis of dementia, one had a diagnosis of isolated memory impairment and two had other conditions leading to social impairment. All 44 patients were included in the study, as under DVLA rules all should inform the medical branch of their condition. The notes of 34 (77%) of these patients had no documented evidence of any discussion relating to driving. The remaining ten patients (23%) had clear evidence of driving status recorded: four patients (9%) were no longer driving and six (14%) were still driving when the issue had been discussed. All of the six patients known to be still driving had been advised to contact the DVLA, but this was only followed up in two cases to ensure that it had been done.

Fig. 1. Questionnaire used in the audit (DVLA, Driver and Vehicle Licensing Agency; RMO, responsible medical officer).

Six months after the questionnaire was implemented we performed the second audit cycle, including all patients who had been admitted to the Elms during the 6-month period. The same gold standard was applied. During this period 38 patients were admitted, all of whom had a diagnosis of dementia. Questionnaires were found in all of the patients’ notes. In 36 (95%) of the cases there was evidence (from the questionnaire) that driving had been discussed. In the other two cases, questionnaires were filed in the notes but had not been completed; there was no documentation elsewhere in these notes that driving had been discussed. Of the 36 patients whose driving status had been documented, 33 (92%) were not driving and no further action was taken. One patient had decided to sell her car after the issue was discussed with her and she had had access to relevant support and information. The other two patients were advised to contact the DVLA. The issue was discussed within 1 month, at which point they confirmed that they had contacted the DVLA medical branch.

Discussion

The results demonstrate that prior to implementation of the questionnaire the issue of driving was discussed only sporadically. Appropriate advice was given when patients were found to be driving, however. The issue was only discussed again in a minority of these cases. Following the implementation of the audit questionnaire, the vast majority of patients had had the issue of driving discussed with them. Only a small minority of patients were found to be driving, and in these cases appropriate advice, action and follow-up were provided. This ensured that the patient’s insurance would not be invalidated by non-disclosure of medical conditions and also allowed the DVLA medical branch to assess the situation and the appropriateness of a driving licence remaining valid. As a result, the safety of the patient and of the wider public is being better monitored, and legal issues have been addressed.

Following this audit, there is now a plan to implement the audit questionnaire in other dementia services that operate within the trust. It is hoped that this will prove particularly useful in the memory assessment services, where the patients tend to have milder disease and are more likely to be driving. Feedback from staff indicated that the questionnaire was a useful tool and easy to use.

The implications of this audit apply across many fields within psychiatry (and indeed other medical specialties). The DVLA requires drivers to inform them of many mental illnesses and all mental illnesses that have necessitated admission to hospital (Driver and Vehicle Licensing Agency, 2004). In the same way as for those with dementia, non-disclosure of the condition to the DVLA could result in a fine and insurance being invalidated. Contrary to many people’s perceptions, only a minority of patients are likely to have their licences revoked after contacting the DVLA. Use of this questionnaire can provide documentation in the notes that appropriate advice has been provided to patients, and it is a simple, cheap and effective measure.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.