The government recently announced its intention to implement a number of reforms to mental health services, designed to address some of the failings of care in the community (Department of Health, 1998). In addition to the highly publicised plans to increase supervised community accommodation and to change the Mental Health Act, the package of measures included a strong endorsement of home treatment for those with acute psychiatric disorder.

This form of community intervention typically involves a home treatment team comprising psychiatric nurses, psychiatrists, social workers, and other professionals, available on a 24-hour basis. The team might make several visits per day to patients who otherwise would have been admitted to hospital, continuing the intensive support for the duration of the crisis (Reference HoultHoult, 1986).

Because the professionals involved see the patient in their home environment there tends to be a greater awareness of important social stressors such as poor housing, financial hardship or relationship difficulties. Hence, it is possible to address practical issues which are often perceived by patients as their most significant problems, in addition to providing medication and psychological interventions (Reference Stein, Hall and BrockingtonStein, 1991). Joy et al (Reference Joy, Adams and Rice1998) concluded that other advantages of home treatment include greater cost-effectiveness, a reduced loss to follow-up, and less family burden, with greater acceptability for both patients and relatives.

Although the ethos of home treatment is to avoid hospitalisation, where possible, it is recognised that for some patients, including those treated under certain sections of the Mental Health Act, hospital admission is inevitable. Other advantages of hospital admission include situations where severe mental illness results in high levels of aggression. Hence the ongoing provision of adequate numbers of high quality in-patient beds remains an important part of service provision for those with acute psychiatric disorders.

At present there is little information concerning the extent to which home treatment has already been implemented, or how many mental health providers are planning such services for the future. In addition the attitudes of health authority purchasers and mental health trusts towards home treatment are unknown. If community psychiatry is to be developed in the direction of home treatment then it will be important to understand the views of future providers concerning possible problems or advantages of such moves.

Objectives

The aims of the study were two-fold. It was hoped to assess the current levels of access to home treatment, and future plans of trusts and purchasing authorities to provide such services. The second objective was to ascertain the views of health authority purchasers and mental health trusts concerning the desirability of home treatment, and more specifically to assess perceived advantages and problems associated with it.

The study and analysis

A postal survey of all mental health trusts, and health authority purchasers throughout the UK was carried out between August and December 1998.

A simple questionnaire was developed, explaining the objectives of the study, and defining home treatment. It was addressed to the chairs of health authorities and chief executives of trusts, and comprised factual questions concerning current provision of community services, and any future plans to implement home treatment. In addition respondents were asked to rate on a visual analogue scale the overall desirability of home treatment, and whether each of a number of factors influenced the desirability of home treatment in either a positive, negative or neutral manner. Comments were invited for other possible advantages or problems associated with home treatment.

Findings

Response rates

A total of 229 mental health trusts were identified and sent questionnaires, of which 172 were returned, representing a response rate of 75%. Of the 123 purchasing authorities, 82 (67%) returned completed questionnaires.

Current provision of home treatment

Twenty-seven (16%) of the 172 trusts indicated that they provide home treatment as defined in the study. Of these all except one was in England, with none in Wales or Northern Ireland (Fisher's exact two-tailed significance=0.031). Among the 27 trusts providing home treatment 17 (63%) had only one team available. There were seven (26%) trusts where home treatment was available to the entire catchment population, although in 14 (52%) cases it was available to only half or less of patients in the area.

Future plans to provide home treatment

Of the 145 trusts not already providing home treatment 58 (40%) were planning to develop such a service in the future. Health authorities were also keen to implement home treatment with 34 (51%) of the 67 not already doing so stating that they had plans to purchase it. Of health authorities and trusts which intended to develop home treatment in the future 14 (41%) and 31 (53%) respectively expected this to be available by the end of 1999.

Reasons for not providing home treatment

In 13 (15%) of the trusts not intending to provide home treatment clinical resistance was a factor, compared with six (19%) of purchasers (Fisher's exact significance=0.572). A lack of financial resources was given as significant by 61 (69%) of trusts, but by only 13 (42%) of purchasers (χ2=6.884; P=0.009).

Attitudes towards home treatment

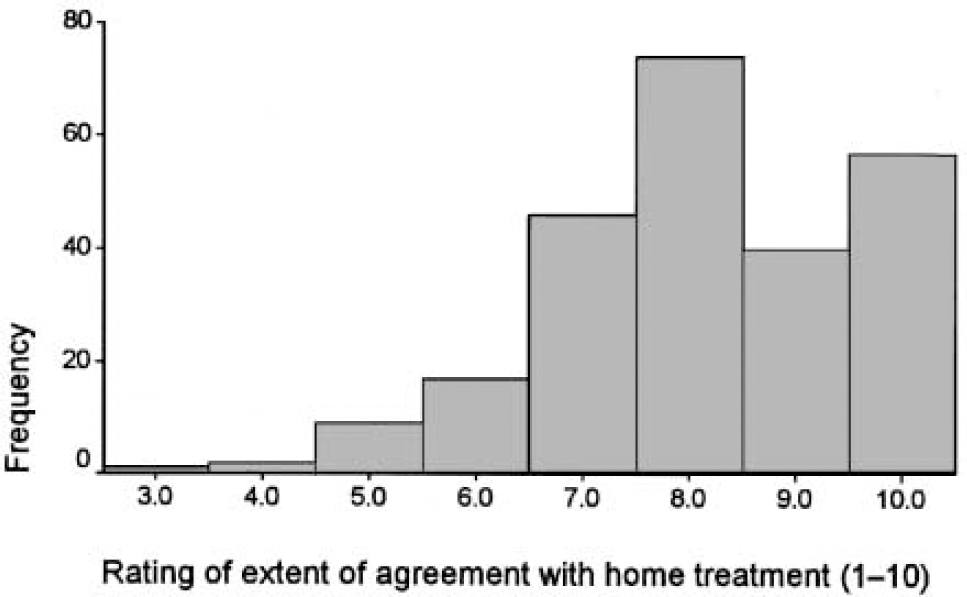

Purchasers and providers were asked to complete a visual analogue scale indicating the extent to which they agreed with home treatment as an adjunct to hospitalisation, ranging from one (undesirable) to 10 (highly desirable). The responses were overwhelmingly in favour of home treatment with only four (3%) of trusts and no purchasers rating less than five. The combined responses are shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Visual analogue scale responses. Combined results for trusts and purchasers. 1, undesirable; 10, highly desirable.

Responses to questions concerning factors which may act to make home treatment either more or less attractive revealed remarkably similar responses from purchasers and providers, with no significant differences. These are given in Table 1.

Table 1. Influence on the desirability of home treatment compared with hospital admission for all respondents

| Favours home treatment | No influence | Favours hospital admission | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | (%) | n | (%) | n | (%) | ||||

| Clinical effectiveness (n=227) | 132 | (58) | 56 | (25) | 39 | (17) | |||

| Financial cost (n=232) | 87 | (38) | 68 | (29) | 77 | (33) | |||

| Patient acceptability (n=235) | 218 | (93) | 11 | (5) | 6 | (2) | |||

| Public acceptability (n=236) | 25 | (10) | 30 | (13) | 181 | (77) | |||

| Safety to clinical staff (n=233) | 11 | (5) | 79 | (34) | 143 | (61) | |||

| Improvements in social functioning (n=238) | 225 | (95) | 13 | (5) | 0 | ||||

| Prevention of future relapse (n=231) | 175 | (76) | 53 | (23) | 3 | (1) | |||

| Views of relatives (n=204) | 94 | (46) | 43 | (21) | 67 | (33) | |||

In response to invitations for other possible problems or advantages of home treatment several groups mentioned the difficulties of implementing this type of intervention in rural areas, and the need for financial bridging resources. A variety of advantages were mentioned including reducing the problems associated with hospitalisation such as dependence, stigma and illicit drug availability, as well as favouring women and those from ethnic minority groups, and its benefits of better staff recruitment and retention.

Discussion

This was the first survey of current practices and attitudes towards home treatment, and examined these issues from the perspective of both purchasers and providers. The high response rates suggest that its findings are likely to represent an accurate indication of provision of home treatment in the UK. There may have been response bias with trusts providing or planning to provide home treatment more likely to respond.

The study demonstrated that few patients with severe mental illness have access to home treatment. However, many trusts had active plans in place to develop these services and it is likely that the proportion providing home treatment will increase substantially over the next 12 months.

There was a positive attitude towards home treatment by both trusts and purchasers with strong endorsement of the suggestions that compared with hospitalisation it is likely to be more clinically effective, more acceptable to patients, improve social functioning and reduce the likelihood of future relapse.

Many of the benefits of home treatment may more accurately be described as disadvantages of hospitals. This was reflected in the statements that home treatment avoids many of the problems associated with psychiatric hospitals such as dependence, stigma and the widespread availability of illicit drugs.

The main disadvantages of home treatment were the views of the general public, safety of clinical staff and concerns about the applicability of home treatment to rural areas. The latter is a valid concern as the main studies of home treatment have all taken place in predominantly urban areas, and in addition, there are likely to be logistic difficulties in visiting people in isolated areas up to four times a day and being available to visit at night within a reasonable time.

There is no research evidence that staff may be more vulnerable if treatment is provided away from the hospital setting, with no reports of problems of violence to staff in the home treatment studies. It is possible that because community treatment avoids many of the frustrations of hospital, such as boredom, overcrowding and low staff levels, that violence is less likely in the home environment.

Comment

Despite its advantages over hospital admission, home treatment is available to only a small proportion of people experiencing severe mental illness, although there is evidence that this will change substantially in the future. The overwhelming majority of trusts and purchasers appeared to support its implementation in principle and to accept the findings of previous research that it accords greater patient satisfaction, reduced chance of future relapse and gains in both social functioning and mental state. With the ongoing government endorsement of home treatment, backed by financial resources, 24-hour community-based teams are likely to become a standard part of mental health services.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.