The East Sussex Court Assessment and Diversion Scheme started operating in 1993, jointly funded by the Department of Health and the Home Office, to meet the objectives set out by the Home Office (1990) and the Reed Report (Reference ReedReed, 1992). Its aim was to provide appropriate intervention for people with mental disorder charged with a criminal offence, in the least restrictive environment according to risk assessment and the direction of the court. Since 2001, the scheme's funding has been provided solely by the National Health Service (NHS), in accordance with the aims of the National Service Framework (Department of Health, 1999).

The primary function of court diversion is the transfer of people with mental disorders from the criminal justice system to hospital, if their condition warrants it (Reference JamesJames, 1999). Prosecution is not necessarily discontinued. The defendant may be admitted to hospital under a section of the Mental Health Act 1983. A court diversion scheme can also provide a liaison service, in which people with mental disorder facing minor summary charges who would not be incarcerated can be referred to community agencies and services, if their condition does not warrant their admission to hospital. Magistrates courts provide a convenient and timely opportunity to assess defendants, as law dictates that individuals charged with a criminal offence must appear before magistrates early in the criminal justice process, to be remanded either on bail or in custody.

The purpose of this study is to examine the work of the East Sussex Court Assessment and Diversion Scheme between January 2000 and December 2002, with reference to its activity, its identification of defendants with mental disorders and its liability to obtain appropriate care for them.

The East Sussex scheme operates during normal office hours, Monday to Friday (excluding public holidays). The scheme is based at Ashen Hill (regional secure unit) and is led by community forensic nursing staff. Medical cover is provided by a duty roster of Ashen Hill forensic psychiatrists, a provision that is particularly important when considering transferring a defendant to hospital using the Mental Health Act 1983. The main role of the scheme is to provide assessment at the four magistrates courts in East Sussex (Brighton, Lewes, Eastbourne and Hastings) for recently arrested defendants detained in police custody, before their appearance in court. The coordinating community forensic nurse contacts each magistrates court at 9 a.m. to enquire whether an assessment by the scheme is necessary. All professionals involved in dealing with the defendant are encouraged to make a referral. There is also provision to assess people remanded by the magistrates court on bail, and in custody at Her Majesty's Prison (HMP) Lewes.

Method

Data were collected in the course of the normal duties of the scheme members, for a 3-year period from 1 January 2000 to 31 December 2002. Each member noted the source of referral, basic details of the individual and the current charge. They undertook a clinical interview of the individual, and made a primary and secondary clinical diagnosis, as necessary. They made a record of their recommendation to the court and the outcome of proceedings. Their findings have been analysed retrospectively.

Results

During the 3-year period studied, 1830 referrals were made to the scheme, the police being the main referral source (737 referrals; 40%). Since October 2000, the scheme has contacted Premier Prisons, a private company contracted to supervise prisoners in court custody suites, with the result that a significant number of additional referrals (267) have been made. The probation service, magistrates, defence solicitor, local mental health service, social services, prison health care and the voluntary sector contributed to the remainder.

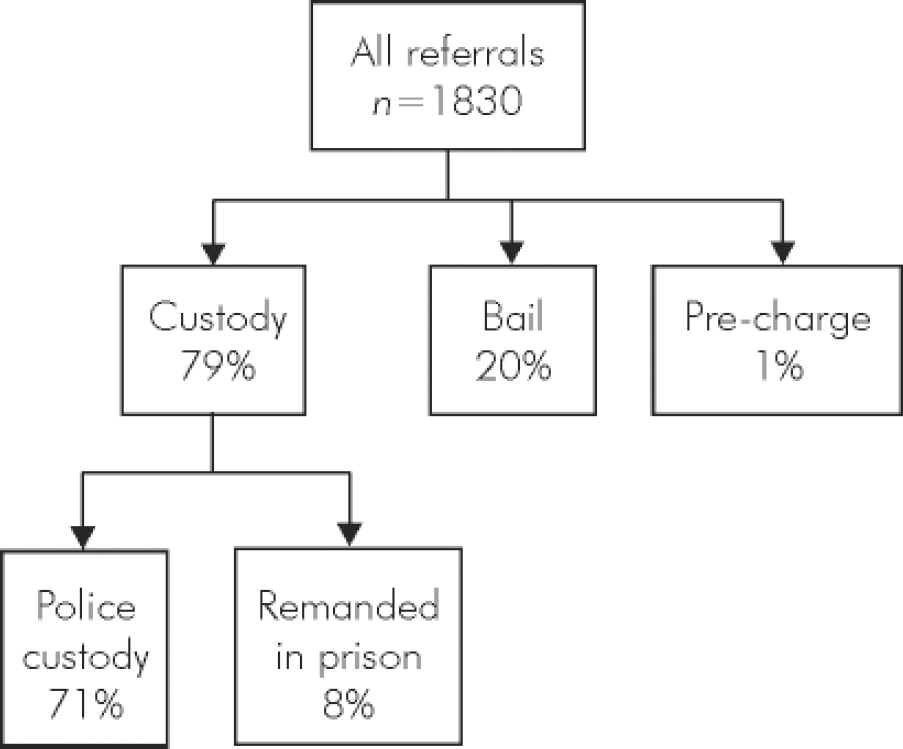

The majority of referrals were of individuals detained in police custody who had been recently arrested (1303; 71%), followed by those remanded by the court on bail (370; 20%) and people who had been remanded by the court in custody in prison at HMP Lewes (141; 8%). The remainder were classified as ‘ pre-charge’, indicating that the police were making investigations, but had not brought a charge (Fig. 1). Most of those referred to the scheme were men (1607 individuals; 88%). In accordance with available resources, the majority of those referred (1527; 83%) were assessed by a community forensic nurse, while 286 (16%) were seen by a doctor, the small remainder having a joint assessment. Owing to a reduction in medical staff available for court diversion duties during the study period, the proportion assessed by a doctor reduced from 23% in the year 2000 to 7% in 2002. Six per cent of referrals (109 individuals) were of people from an ethnic minority, from an estimated ethnic minority population in East Sussex of 2.3% (2001 UK census). Data regarding ethnicity could not be collected for 91 individuals (5%). A wide range of alleged offences were recorded for those referred to the scheme (Table 1).

Fig. 1. Status of referrals.

Table 1. Alleged offences of people referred to the scheme

| Offence | Percentage of defendants |

|---|---|

| Acquisitive | 27 |

| Public order | 19 |

| Minor offences against the person | 15 |

| Breach of conditions | 14 |

| Motoring | 6 |

| Major offences against the person | 5 |

| Sexual | 4 |

| Weapons | 3 |

| Arson | 2 |

| Homicide or attempted homicide | 2 |

| Drugs | 1 |

The ten most common primary diagnoses are given in Table 2, and account for 95% of referrals. In a fifth of the total referrals (367 referrals, 28% of the diagnosed population) the individual was assessed as having a secondary diagnosis: the majority (12% of total referrals) had additional substance misuse problems, and a significant minority (3% of total referrals) had additional depression. Thirty-one people (2% of total referrals) had a comorbid personality disorder.

Table 2. Most common primary diagnoses in people referred to the scheme

| Primary diagnosis | Cases n (%) |

|---|---|

| No diagnosis | 541 (30) |

| Drug misuse | 355 (19) |

| Alcohol misuse | 212 (12) |

| Schizophrenia | 200 (11) |

| Personality disorder | 170 (9) |

| Depression | 134 (7) |

| ‘ Other’ psychosis | 40 (2) |

| Mania/hypomania | 37 (2) |

| Learning disability | 34 (2) |

| Dementia | 16 (1) |

Outcome

Following assessment, no recommendation regarding diversion or liaison was made for 945 individuals (52%), diversion or liaison was recommended for 858 (47%) and the remaining cases were unresolved. The court rejected a recommendation for diversion or liaison on 77 occasions (4%). Most of the rejections related to recommendations for community interventions for people who had primary substance misuse problems or minor mental health problems, which did not warrant their admission to hospital, for whom the court deemed incarceration more appropriate. On 19 occasions (1%), people who were referred for admission to a psychiatric hospital were considered by representatives of that service not to warrant admission. It is known that seven of these individuals were eventually admitted to hospital, four accepted psychotropic medication in prison so that their condition improved, and in three symptoms resolved spontaneously in prison. Without further consultation, the court rejected a recommendation for diversion for admission or residential placement and released the defendant on seven occasions. At least four of the individuals concerned presented to mental health services again soon afterwards.

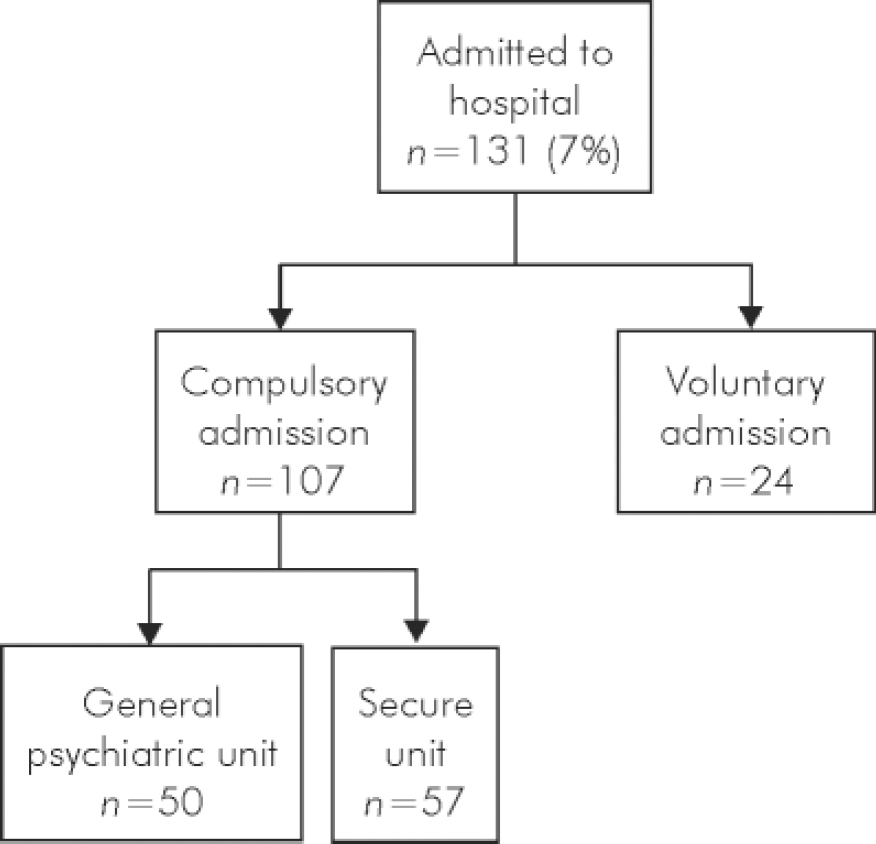

Of those for whom the recommendation of diversion or liaison was successful (781; 43%), the majority were referred to community interventions, either to out-patient psychiatric services or to drug/alcohol treatment; 131 (7%) were admitted to hospital (Fig. 2). Of the 107 individuals who were admitted under the terms of the Mental Health Act, 50 were admitted to general psychiatric beds and 57 to secure unit beds. Twenty-four admissions were made informally to general psychiatric beds. Patients admitted to general psychiatric beds were generally transferred the same day.

Fig. 2. Outcome for people admitted to hospital.

The number of individuals admitted to secure psychiatric facilities increased sharply from 15 each in 2000 and 2001 to 27 in 2002. The average delay in admitting a patient into a secure bed was 8 weeks in 2000, rising to 13 weeks in 2002. These people were remanded in prison in the meantime.

Of the 42 people referred to the scheme charged with homicide and attempted homicide offences, 6 were considered to have a personality disorder, 5 to misuse substances and 4 to have a severe and enduring mental illness as a primary diagnosis.

Discussion

Although the majority of individuals assessed by the scheme were seen in court custody suites soon after their arrest, a substantial minority were seen when remanded on bail or in prison. Therefore, our results are not strictly comparable with those of diversion schemes that operate solely within a court. Nevertheless, some comparisons can be made. Other schemes have found similarly high rates of alcohol and drug misuse in referred individuals, amounting to approximately a third of referrals in Glasgow (Reference White, Ramsay and MorrisonWhite et al, 2002) and Leeds (Reference Greenhalgh, Wyhe and RixGreenhalgh et al, 1996). The proportion of people diagnosed with a major mental illness varies greatly between published studies, and may reflect the threshold of suspicion in the person making the referral.

In this study, referring agencies generally recognised the presence of mental disorder reasonably accurately in the people they referred, so that 70% of those referred warranted a diagnosis. However, it is not known how many people with mental disorder were unrecognised as such and not referred to the scheme. A study conducted in Manchester examined whether defendants with mental disorder were reliably detected by court staff and referred to the court diversion programme (Reference Shaw, Creed and PriceShaw et al, 1999). Only 14 of 96 defendants from overnight custody with serious psychiatric disorder were detected and referred by court staff. Considering this low rate of detection, the authors suggested that screening questionnaires and training might increase the rate of detection. The resource implications are immense. If court diversion schemes are detecting only 16% of cases of serious psychiatric disorder, improving the rate of detection would increase the demand for court diversion mental health staff, requiring greater NHS resources to meet this increased demand. Given this and the high rates of disorder found in a psychiatric morbidity survey of remanded prisoners (Reference Singleton, Meltzer and GatwardSingleton et al, 1998), it may be that although court diversion schemes are successfully identifying a proportion of people with mental disorder and diverting some away from the criminal justice system, a substantial number are not identified, and others are deemed unsuitable for diversion.

In this study, the scheme was able to refer individuals directly to community drug and alcohol treatment services, an important measure considering 43% of those referred had problems with substance misuse (taking together primary (31%) and secondary (12%) diagnoses). This availability of access is unusual for a court diversion scheme, and reflects improvement in services treating substance misuse, particularly in Brighton. Psychiatric community and hospital services were available for those with other mental disorders.

Regarding short-term outcome, the success of this scheme is demonstrated by completed diversions to either community or hospital treatment, as recommended. Medium and long-term success in terms of health, social and offending outcomes are beyond the scope of this study, but are examined elsewhere. James et al (Reference James, Farnham and Moorey2002) studied 214 admissions through the courts in central London, the Horseferry Road and Clerkenwell schemes, comparing them with a sample of 214 matched compulsory admissions from the community. They examined the outcome of admission through the courts in terms of the admission episode, readmission and reconviction rates within 2 years of discharge: 81% of admissions from courts reached planned discharge, with no significant difference between court and community admissions; 86% reached satisfactory clinical outcome at discharge, again with no significant difference between court and community admissions. There were similar readmission rates between the two groups and relatively low offending rates compared with individuals given other disposals by the court.

James (Reference James1999) found that three court diversion studies prepared for publication had admission rates of more than 25%, and indicated a wide variation of admission rates in others, with some schemes not diverting any cases to hospital. Few schemes were able to achieve admission to locked beds. The East Sussex scheme had an admission rate of 7% between 2000 and 2002, with the majority of recommendations for admission being accepted. Admission to secure unit beds was not uncommon, and may reflect the scheme being run within the forensic psychiatry directorate. Although James (Reference James1999) considered that courts tend to deem community disposal inappropriate, this study found that courts generally accepted recommendations for referral to community psychiatric or substance misuse services. The rate of default from these appointments is unknown, and warrants further study.

The recommendations of the scheme were rejected in a small, but significant, minority of cases. On the whole, this reflected the role of the court in delivering punitive justice for individuals who did not require admission to hospital. A substantial proportion of individuals referred by the scheme to hospital and not admitted initially were admitted at a later date, had symptoms that resolved in prison, or presented again. This suggests that the quality of clinical assessment made by scheme members was high.

Although admissions to general psychiatric beds were effected quickly, admissions to secure units were delayed, and this problem appears to be worsening. This seems to be the result of the combination of increased referrals and a shortage of secure psychiatric provisions. A lack of secure psychiatric beds is a common shortfall for psychiatric services, leading to such delay (Reference Isherwood and ParrottIsherwood & Parrott, 2002). It is unlikely that the increase in admissions to secure units is due to changing admissions policies, as the Eastman criteria (Reference EastmanEastman, 1998) have been employed throughout the 3 years of this study. The expansion in secure psychiatric facilities needs to continue.

A relatively high proportion of individuals from an ethnic minority were referred to the scheme. This may indicate that they may be more likely to be charged with a criminal offence, kept in custody or suspected to have a mental disorder than their White counterparts. This requires further study, but it is noteworthy that Black males are over-represented in all secure settings, whether hospital or prison (Reference Coid, Petruckevitch and BebbingtonCoid et al, 2002).

Less than 1 in 10 people referred to the scheme facing charges relating to homicide and attempted homicide were assessed to have a primary diagnosis of severe and enduring mental illness, with both substance misuse and personality disorder being more prevalent. No clear conclusion can be drawn from this, considering the bias that may exist at the referral stage and the small numbers involved.

Clearly there are limitations to this study. Because of the naturalistic nature of the data collection, rigorous research diagnostic criteria have not been applied, and diagnoses were made by the assessors largely on the basis of a single clinical interview. Errors in diagnosis might have resulted. Tertiary diagnoses have not been included in the analysis. However, it does reflect clinical practice, giving an overview of the type of individual referred to a court diversion scheme, the conclusions and recommendations that may be made, and the response of the court and service providers to these recommendations.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.