The aim of the defence medical services (DMS) is to maintain the health of those individuals who volunteer for service in HM Armed Forces, in order that they may efficiently discharge their duties.

Military psychiatry is therefore an occupational service in which the military psychiatrist has responsibilities to both the individual and the organisation, rather like forensic psychiatrists and prison doctors. Military culture is distinct from civilian culture and offers a unique social environment in which to practise psychiatry.

There is no civilian equivalent to military psychiatry; the closet would be liaison psychiatry. There is, however, an interesting mix of adolescent, forensic, psychotherapy (individual and group), rehabilitation psychiatry (physical, including injury, and psychological injury), public health, occupational medicine and transcultural work. Serious mental illness, other than index episodes of psychosis is rare. Personality differences, post-combat (traumatic) mental health issues; somatisation; abnormal illness behaviours; sequellae of childhood abuse; reactions to extreme stress; the effect of hostage taking; teaching (para-and non-medical personnel); providing psychological advice and psychological ‘threat’ assessments for commanding officers; working with welfare and religious organisations; undertaking psychological autopsy; aviation and underwater psychiatry; and so forth are all part of a uniformed psychiatrist's remit.

DMS psychiatry is tri-service and serves 210 000 service personnel (and when abroad, their dependants). The service is community-based in departments of community psychiatry (DCP) with an in-patient assessment and treatment facility in North Yorkshire at the Duchess of Kent's Psychiatric Hospital. Each DCP manages around 4000 new referrals and 20 000 out-patients per year. The in-patient unit receives approximately 450 new patients each year and acts as a triage and receiving centre for psychiatric aero-medical evacuations. The DMS employs a large number of civilian psychologists, nurses and psychiatrists.

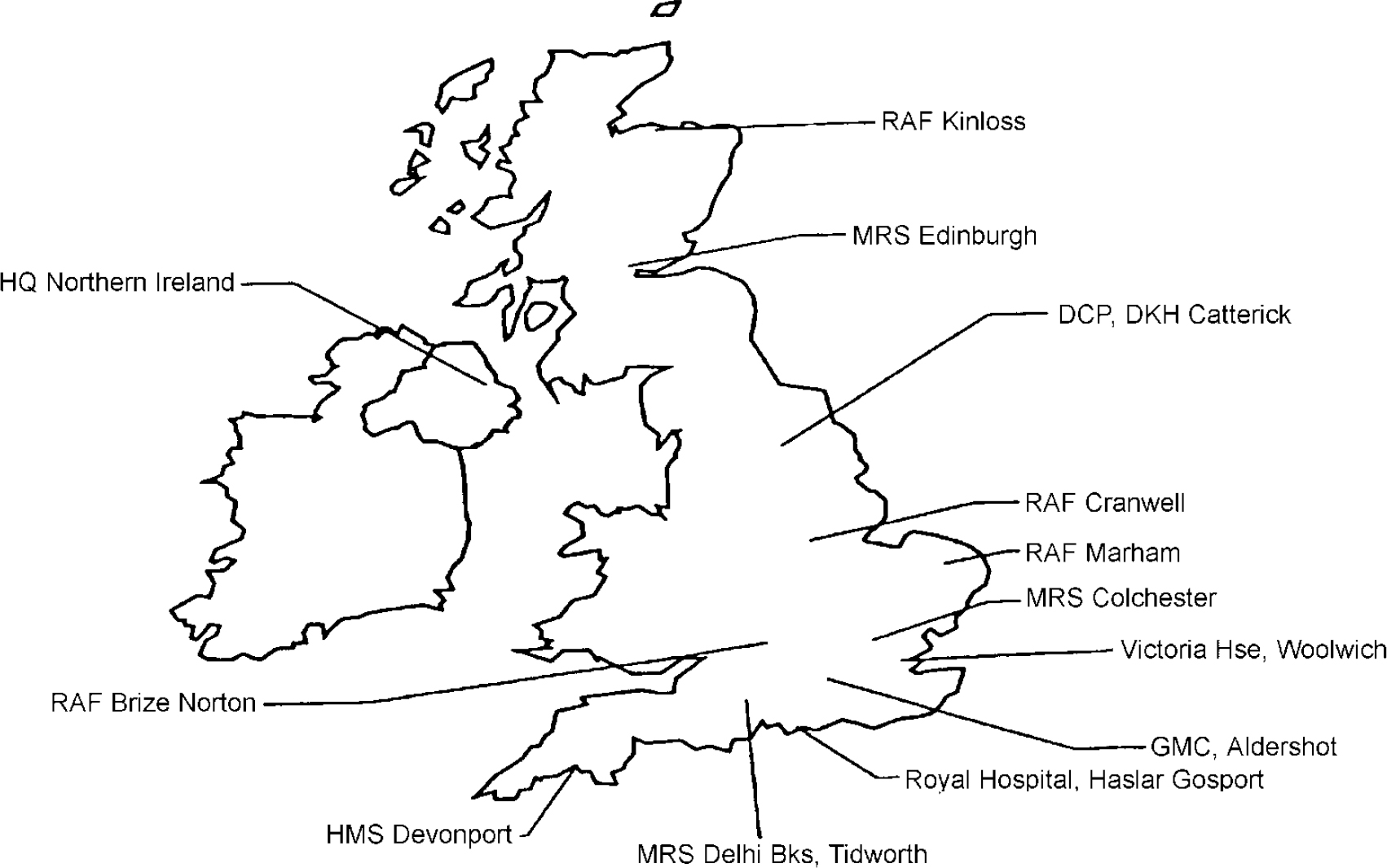

There are 16 DCPs in the UK (Fig. 1), Germany, Gibraltar and Cyprus. Each serves a catchment population of approximately 15 000 servicemen and consists of consultant psychiatrist(s) and community psychiatric nurses with psychology and social work support.

Fig. 1. Departments of community psychiatry (UK).

Origins of military psychiatry

Military psychiatry can look to 1904/1905 as its birth date. It was the Russians who first enunciated the basic principle of military psychiatry relating to the social context of an individual's distress. They found that when soldiers were removed from the social role and evacuated from combat their psychological symptoms became fixed and they suffered the long-term mental illness, the so-called evacuation syndrome. They also found that the symptoms of many of those soldiers who were kept close to the front, with their colleagues and units, improved, indeed some could even return to duty.

World War One revealed that every man has his breaking point. World War Two showed the importance of the group dynamic before, during and after combat in protecting and supporting combatants. The Vietnam War reminded us of the long-term psychological sequelae of combat. The Yom Kippur served as a reminder that acute psychological breakdown could occur rapidly. The Gulf War reminded us of post-conflict war syndromes seen first in Scottish and Swiss mercenaries in the 18th century.

Psychiatric casualties are now as much a part of military medical planning as infectious diseases and gunshot wounds. Their initial management is primarily the responsibility of command. Their subsequent management the responsibility of medical officers and psychiatrists, a task with its unique moral and ethical dilemmas.

Current service organisation

Defence psychiatry is coordinated through the Defence Director of Psychiatry, a senior consultant psychiatrist with a role similar to a NHS trust chief executive. It is part of the Defence Secondary Care Agency that acts like an NHS health authority (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Current service organisation. DMS, defence medical services; PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder; OT, occupational therapy; DCP, departments of community psychiatry; RMNs, registered mental nurses; CPNs, community psychiatric nurses.

In-patient services

The Duchess of Kent's Psychiatric Hospital has 20 beds and a day hospital. There are general adult, substance misuse, psychological injuries, medical discharge, rehabilitation and military re-training teams. Social work, psychology and occupational therapy departments are staffed entirely by civilians. As the Duchess of Kent's Psychiatric Hospital is not a hospital within the meaning of the Mental Health Act 1983, ‘Sectioned’ patients are detained in local NHS facilities.

The military re-training team is a form of social therapy with its genesis in World War One and aims to reintegrate service personnel into military life by using elements of group and physical activities undertaken in a military environment. The psychological injuries team provide a comprehensive 3-day assessment and treatment package and, where comorbidity exists, there is close liaison with substance misuse services.

Where it is decided that an individual's prognosis is not compatible with continued military service, a comprehensive package of care is organised, aiming at reintegration into civilian life and social work follow-up is organised for the 12 months following discharge.

Challenges

Military psychiatrists have three roles: psychiatrist, doctor and officer. In time of crisis and conflict the organisation rather than the individual is the ‘patient’. It therefore beholds military psychiatrists to undertake military training in order to understand the role of the military in modern society; the structure and functioning of the organisation and, to be effective, identification with the military culture and those individuals who volunteer to serve their country. There is no civilian equivalent to combat psychiatry. At times of crisis military psychiatrists may find themselves helping-out and practising general medicine (indeed many will have training in general practice — one even delivered babies in Rwanda).

They are uniquely placed to influence occupational and social factors as they relate to unit and individual mental health and therefore are required to develop interpersonal and teaching skills that allow them to influence commanders, individuals and groups. Military psychiatrists may be tested physically, intellectually, emotionally, ethically and morally, some will witness history in the making.

Current serving psychiatrists have had key roles to play in the Gulf War, Former Republic of Yugoslavia, Rwanda and hostage-taking situations. Some have served with Royal Marine Commandos; the SAS; Parachute Field Ambulance; and Highland Regiments, others have circumnavigated the world onboard a warship or worked on submarines and have worked as part of the RAF's aeromedical evacuation team. There is an annual military psychiatric conference open to all NATO, Partnership for Peace and Commonwealth countries.

Training

Most join the services while at medical school. All entrants have to undertake a period of military training after which they will undertake training in advance trauma life-support and advance life-support techniques, tropical medicine, rehabilitation services, sports medicine and aspects of chemical and biological warfare to name but a few.

Prior to undertaking training in psychiatry all trainees undertake general medical ‘duties’ in order to experience and understand the environments in which their patients live and work. This training and work gives direct managerial and people management experience to junior doctors from the outset of their career. Without this experience they are valueless, as they will not understand the organisation and individuals they support. Most individuals look upon their military training and experiences fondly.

Currently general psychiatric training is based in North Yorkshire and integrated into the Leeds scheme; there is ample support for courses and membership training. There are opportunities for time away from the scheme and as trainees receive a military salary many NHS trusts are happy to offer placements, as they are effectively ‘free’.

Specialist registrars (SpRs) may undertake their training at centres of excellence of their choice. Most, however, take advantage of the excellent North Yorkshire rotation. Liaison psychiatry is the preferred speciality as training mirrors more closely service psychiatry than any other NHS sub-speciality. It also provides great flexibility in training to reflect individual interests. National training numbers are allocated to SpRs by the Defence Services Postgraduate Dean, who is responsible for overseeing their training.

As a consultant there is scope to work in both community and in-patient settings. Active continuing professional development is encouraged and well-funded in terms of time and finances. With opening of the Centre for Defence Medicine in Birmingham there will be increased opportunities for academic work with an emphasis on occupational, health education, epidemiological, sociocultural and organisational aspects of military psychiatry.

Research, audit and clinical governance

While much of the research is based clinically, there are opportunities to become involved and sponsor research in areas such as post-deployment surveillance, occupational medicine, social and epidemiological surveys, etc. There is close clinical liaison with general practice as well as public health, occupational, rehabilitation and general medicine.

Current clinical research relates mainly to psychological injury; risk assessment; computer administered cognitive therapy for affective and anxiety disorder; substance misuse epidemiology; post-conflict war syndromes and medically unexplained symptoms following combat. Regular in-patient and community clinical audit is held to monitor quality and effectiveness in both the settings. By applying clinical governance, military psychiatry strives to provide evidence-based practice and a first class service.

Conclusion

Military psychiatry is unique. It is not a special interest group; it is part of a national psychiatric resource that offers a markedly different cultural and clinical experience. Clinical care is but one facet of a job in which there is the opportunity to recognise, intervene and manage mental ill health at an earlier stage than would normally be possible, thereby (hopefully) having a positive impact on prognosis and future occupational abilities. Few NHS psychiatrists will encounter such a diversity of challenges or experiences.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.