Have you ever wondered why the well-known Mill Hill Vocabulary Scale was named after a suburb of North London? Little known to most psychiatrists or to local people in Mill Hill, a major part of the Maudsley Hospital was evacuated there from central London during the Second World War. Mill Hill School had been evacuated en masse to St Bees in Cumberland. The vacant buildings were requisitioned by the Emergency Medical Service for the Maudsley Hospital. Much innovative psychiatric treatment and research took place there throughout the war with a star-studded cast, including some outstanding clinicians and researchers. This brief review of historical sources aims to give a flavour of the clinical work of the Mill Hill Maudsley.

The directors

The leadership of the Maudsley in war time was no easy task. At the top of the hierarchy was Medical Superintendent Dr Walter Maclay. Awarded the OBE in 1943, he was quoted as saying ‘I’m a compromiser… so long as I get my own way’. He was later highly instrumental in developing the Mental Health Act 1959, laying the legal foundations for providing community care (Anon, 1961). His deputy was Aldwyn Stokes, later professor of psychiatry in Toronto (Reference Jones and WilkinsonJones, 1983). The clinical director was Aubrey Lewis, later Professor Sir Aubrey Lewis, under whose leadership the academic and clinical reputation of the Bethlem and Maudsley Hospitals and Institute of Psychiatry was established. Some of those whose early careers Lewis nurtured at Mill Hill later become internationally renowned. However, there were tensions between Lewis and Maclay, between the military and civilian management of the hospital and between various practitioners, for example, those related to record-keeping and the need for follow-up after 1 year to look at outcome of treatment (Reference Jones, Angel, Jones and NeveJones, 2003). Edward Mapother, the Maudsley's first professor of psychiatry, did not live to see the work done at Mill Hill, but died in the hospital from asthma and pulmonary fibrosis in 1940 (Reference HaywardHayward, 2004).

The cast

Lewis was an early advocate of multidisciplinary team working, influenced by Adolph Meyer, reformer of mental healthcare in the USA (Reference Gelder, Berrios and FreemanGelder, 1991). Among Lewis’ team were child psychiatrist William Hewett Gillespie (Reference GillamGillam, 2004), the eminent psychologist Hans Eysenck, Felix Post then in his first psychiatric job and later a pioneering old age psychiatrist, and the charismatic Alex Baker, later first director of the Hospital Advisory Service (Reference Baker and WilkinsonBaker, 1990). There was Maxwell Jones, pioneer of the therapeutic community, and academic neurologist and psychiatrist Eric Guttmann. Annie Altschul, having fled Austria under threat of Nazi persecution, gained her psychiatric nursing qualifications at Mill Hill, later becoming Professor of Nursing Studies in Edinburgh. Of Mill Hill she wrote:

‘I found an excitement about the work that I had not encountered before. The staff…were very keen and every patient was regarded as interesting and someone from whom we could learn a lot. I worked with people I had only read about till then’. (Cited in Reference NolanNolan, 1993)

Aubrey Lewis invited Hans Eysenck, who had also fled from Nazi persecution, to Mill Hill. Eysenck's appointment proved to be the fulcrum of his career with the launch of his research on personality. One of his first major works, Dimensions of Personality, was commenced at Mill Hill. He later became Professor of Psychology at the Institute of Psychiatry (Reference RichardsRichards, 2004). Much work was done on personality, Aubrey Lewis ensuring that patients had a personality assessment and short training courses in engineering or clerical work to improve their employment opportunities when they left the hospital (Reference Cramer and FreemanCramer, 1999). The psychology department also included John Carlyle Raven, conscientious objector who developed and validated the Progressive Matrices and the Mill Hill Vocabulary Scale (Raven, Reference Raven1940, Reference Raven1943). Footnote 1 Meanwhile, preliminary research on mental tests in senile dementia (Reference HalsteadHalstead, 1944) coincided with the very early development of the specialty of old age psychiatry, a subject for which Aubrey Lewis showed particular interest (Reference LewisLewis, 1946).

The drama

Effort syndrome and other clinical work

Both service personnel and civilians were admitted, many were also physically injured. Much of the clinical work focused on treating the emotional traumas of war, in particular, effort syndrome. Previously known as ‘ soldier's heart’, Sir Thomas Lewis coined the term ‘ effort syndrome’ in 1917 to emphasise the lack of cardiac pathology (Reference HollmanHollman, 2004). Causes, psychopathology and management were further described by Maxwell Jones and Aubrey Lewis in the Lancet (Reference Jones and Lewis1941).

One junior doctor described his impressions of effort syndrome and its clinical management:

‘Some were from Dunkirk, but most were just ordinary service people, who had broken down with the stress of being in the army, just being in the army, being away from home, being drilled, the danger to come.

Effort syndrome is… a condition when people exert themselves, they begin to feel breathless, have pain in the chest, and general exhaustion…. The main thing was to assure them about their heart, which wasn't usually very well received, because the motive of getting out of the army was all too obvious in most cases I think…. I do not remember any one who was accused of malingering. They all had the symptoms you see… signs like tachycardia, which you can't malinger… and also anxiety.

There were women patients in one of the out lying villas. I had my room there, Professor Lewis later referred to me“you are the phallic symbol there”. The women were air raid casualties and also from women's services.

One man had a severe anxiety state after he had been torpedoed, and so I hypnotised him and took him through his experiences, reliving this ship wreck, this torpedoing… and so on, and then I brought him out of hypnosis, only to discover very soon that he was still on the ship which had rescued him, still in danger, so I had to rehypnotise him to bring him back to the hospital.

It was one of the ways we helped people… either tohypnotise them or to put them under narcosis, semi-narcosis with sodium amytal injections, and then they would relive their experiences. I think it was a treatment which was very effective if given soon after the trauma. Of course by the time they came to us, the trauma was a long time away, so it wasn't quite so effective.

There was psychotherapy, letting them talk, listening to them, interpreting the real meaning of some of their symptoms, and so on’. (Reference PostPost, 1996)

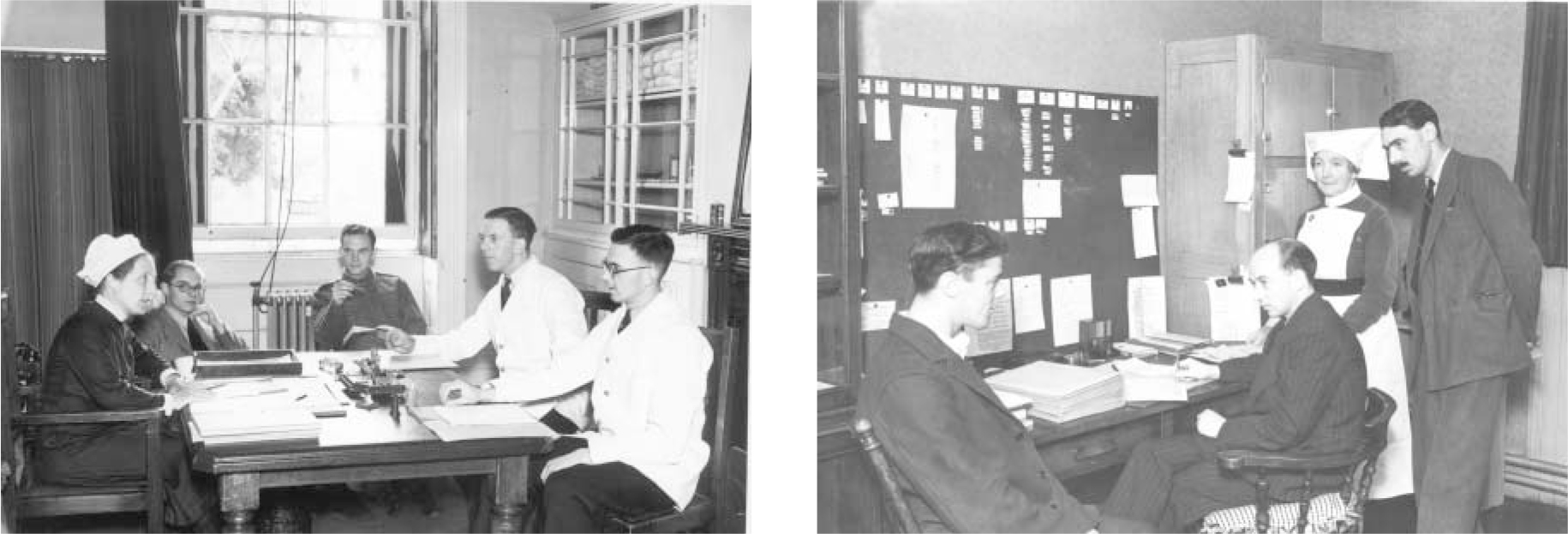

On the stage. The archives of the Bethlem and Maudsley Hospital hold many photographs of the Mill Hill Emergency Hospital. Many are unlabelled. If any reader can assist in identifying the characters in these photographs it would be greatly appreciated.

Individual psychotherapy was well established by the 1940s, but only in private practice; it was never widespread during the war nor in the armed forces (Reference JonesJones, 2004). Partly owing to staff shortages and a large workload, large group psychotherapy was introduced. New ideas were developed at Mill Hill by Maxwell Jones, in particular, that treatment was a continuous process operating throughout the day and over every aspect of the patient's life, with both patients and staff working together as a team, notions central to the therapeutic community ideology. The Mill Hill work complemented that undertaken at psychiatric establishments elsewhere (Reference Millard and FreemanMillard, 1999), but Lewis criticised Jones for his lack of statistical methods to evaluate outcome (Reference JonesJones, 2004).

Clinical work went hand-in-hand with research. Psychiatric social worker Helen Goldschmidt included residents of an elderly persons’ housing estate in Mill Hill in her study of social aspects of ageing and senility (Reference GoldschmidtGoldschmidt, 1946). Elizabeth Rosenberg and Eric Guttmann - later to marry - wrote an article entitled ‘ Chronic neurotics and the outbreak of war’ based on data from out-patient clinics in inner London (Reference Rosenberg and GuttmannRosenberg & Guttmann, 1940). ‘Anxiety and the heart’ and ‘The psychology of pain’ were also by Guttmann, co-authored with fellow refugee psychiatrist Willi Mayer-Gross who had recently moved from the Maudsley to the Crichton Royal Hospital in Dumfries (Guttmann & Mayer-Gross, Reference Guttmann and Mayer-Gross1940, Reference Guttmann and Mayer-Gross1943). Alex Baker later recalled Guttmann at Mill Hill:

‘He was so helpful and supportive to a young doctor, particularly one like myself who was naïve, incompetent and ignorant. I was indebted to him and always will be’. (Reference Baker and WilkinsonBaker, 1990)

Felix Post was also a refugee. Both he and Guttmann suffered the indignity of being interned on the Isle of Man as enemy aliens (Reference Post and WilkinsonPost, 1988), as did Adam Limentani, an Italian psychiatrist working in Mill Hill with casualties from Dunkirk, when he was arrested along with many other Italians after Italy joined Germany in the war (Reference LimentaniLimentani, 1994). Many years later Post reflected on Mill Hill in 1941:

‘I experienced the fascination of the hypnotic sessions… and witnessed the first beginnings of Maxwell Jones’approach to neurotic problems, which were initially group-didactic rather than group-therapeutic…. My very first experience at Mill Hill was having to assist with the setting of a humerus fractured during a cardiazol fit. The far less distressing electroconvulsive therapy, which was demonstrated to us a few months later… was only a shade less unpleasant to work with and to administer; but it did work’. (Reference PostPost, 1978)

The Mill Hill Maudsley was one of the earlier hospitals in Britain to introduce electroconvulsive therapy (ECT). This therapy, described in the Lancet in 1939 (Reference KalinowskyKalinowsky, 1939), had still not entirely supplanted cardiazol-induced seizures by 1944 (Reference Sargant and SlaterSargant & Slater, 1944). Lewis permitted ECT but not leucotomies or insulin therapy, although these were carried out in the other part of the evacuated Maudsley in Sutton (where Sargant and Slater were deputy clinical director and clinical director, respectively), a source of clinical therapeutic tension when the two branches of the Maudsley reunited in Denmark Hill, London after the war (Reference Jones, Angel, Jones and NeveJones, 2003). After the war other challenges followed (Reference Waddington, Gijsurijt-Hofstra and PorterWaddington, 1998) including the merger with the Bethlem Royal Hospital under the new National Health Service, the development of the Institute of Psychiatry, and the post-war modernisation of clinical psychiatric practice.

Declaration of interest

None.

Acknowledgements

This research was undertaken while I was in receipt of a Wellcome Trust Research Leave Award in the History of Medicine (grant no. 073163). I am grateful to Edgar Jones (Maudsley Hospital) and Colin Gale (Bethlem and Maudsley Archives) for their help in preparing this paper.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.