At some point during their illness 90% of patients with dementia develop a behavioural disturbance (Reference Ballard and OyebodeBallard & Oyebode, 1995). These behavioural and psychological signs and symptoms of dementia (Reference Finkel, Costa e Silve and CohenFinkel et al, 1996) are varied in presentation and aetiology, and encompass three syndromes, two behavioural (overactivity and aggression) and one psychotic (Reference Hope, Keene and FairburnHope et al, 1997). Approximately one-third of people with dementia in UK residential and nursing homes are prescribed antipsychotics, often without adequate monitoring (Reference Furniss, Craig and BurnsFurniss et al, 1998). Over recent years, concerns about the safety and efficacy of typical antipsychotics such as haloperidol have led many clinicians to abandon these drugs in favour of the newer atypical antipsychotics such as risperidone and olanzapine.

In 2004 the Committee on the Safety of Medicines (CSM) estimated that 39 000 patients with dementia in the UK were being prescribed either risperidone or olanzapine. They reported an analysis of data from several randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of these two drugs and recommended that neither should be used for treatment of behavioural symptoms in dementia because of increased risk of cerebrovascular adverse events and, in the case of olanzapine, a doubling of the mortality rate (Committee on the Safety of Medicines, 2004). They also advised that risperidone and olanzapine for the management of acute psychosis in older people with dementia should be short term and under specialist supervision. In response, the Royal College of Psychiatrists issued guidelines recommending, where possible, a gradual withdrawal of risperidone and olanzapine over 2–4 weeks, citing evidence from RCTs that 45–70% of residents in care homes receiving antipsychotics can be safely withdrawn from medication with no adverse consequences (Royal College of Psychiatrists, 2004a , b ).

A recent audit of patients under the care of South Charnwood community mental health team for older People in Leicestershire (which included persons both at home and in care homes) has demonstrated that, of those with dementia and prescribed olanzapine or risperidone, 58% were able to discontinue antipsychotic treatment completely, and 16% had their medication changed successfully to a benzodiazepine (details available from authors). To examine what was happening to individuals with dementia primarily under general practice care we repeated the audit in care homes.

Method

Ten care homes were selected at random from a list of all of those in Leicestershire. Each care home and the respective GP practices were sent a letter informing them of the audit and seeking permission to visit the homes and inspect residents’ prescription records, both current and prior to CSM advice.

Using a standardised tool the current prescriptions were compared with the prescriptions in the weeks prior to the CSM advice (a gap of 9 months). Owing to difficulty accessing GP computer systems it was not possible to compare GP records with the prescription at the place of care.

The diagnosis of dementia was based on clinical information available at the home, for example from social workers’ reports, hospital discharge summaries, etc. If there was no documentation stating a diagnosis of dementia then the resident was deemed not to have dementia. The senior carer was interviewed to determine the extent of follow-up (i.e. whether under community mental health team (CMHT) or GP review), frequency of review, and reason for the antipsychotic prescription. We found no clear guidelines regarding medication review of older people with dementia. The level of review was categorised as inadequate if the resident was seen less frequently than 6 monthly, or the date of the next review was not known. The cut-off of 6 months is in line with the National Service Framework for older people, which recommends that all people over 75 years and on four or more medicines should have a medication review every 6 months (Department of Health, 2001). The average age of residents in care homes in the UK is 84 years (Reference BajekalBajekal, 2002) and residents are prescribed on average six medications each (Reference Furniss, Craig and BurnsFurniss et al, 1998).

Results

A total of 330 resident's medication charts were reviewed. Out of these individuals, 164 (50%) had documentation which identified them as having a dementia; 75 of the 164 residents with a diagnosis of dementia (46%) were on an antipsychotic at some point in time during the audit period; 11 of the 75 were not resident before the CSM advice and so were removed from the analysis. The antipsychotics prescribed and reasons for their prescription are summarised in Tables 1 and 2.

Table 1. Antipsychotic prescriptions for residents (n=319) before and after the Committee on the Safety of Medicines guidance

| Before guidance | After guidance | |

|---|---|---|

| Risperidone, n | 24 | 9 |

| Olanzapine, n | 13 | 10 (2 new) |

| Quetiapine, n | 3 | 5 |

| Amisulpiride, n | 1 | 1 |

| Haloperidol, n | 2 (+3 as 2nd antipsychotic) | 6 (+2 as 2nd antipsychotic) |

| Promazine, n | 3 (+3 as 2nd antipsychotic) | 6 (+2 as 2nd antipsychotic) |

| Sulperide, n | 7 | 11 |

| Flupenthixol, n | 1 | 1 |

| Chlorpromazine, n | 0 (+1 as 2nd antipsychotic) | 0 |

| No antipsychotic, n | 10 | 15 |

| Total, n | 64 (5 on 2 antipsychotics) | 64 (3 on 2 antipsychotics) |

| On olanzapine or risperidone n/N | 37/54 | 19/49 |

| Atypical:typical ratio | 3.1:1 | 1.04:1 |

Table 2. Reasons for antipsychotic prescriptions

| Psychosis n/N (%) | Behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia n/N (%) | Not clear n/N (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| All antipsychotics | 17/64 (27) | 41/64 (64) | 6/64 (9) |

| Ever on risperidone or olanzapine | 9/391 (23) | 28/39 (72) | 2/39 (5) |

| Continue on risperidone or olanzapine | 7/19 (37) | 11/19 (58) | 1/19 (5) |

With regard to follow up, CMHTs had been involved in the care of 59% (38 out of 64) of residents with a diagnosis of dementia and on antipsychotics (at some point during the audit period). The CMHTs were currently involved with the majority of the residents who had recently been placed within care (6 out of 11). Of the residents with a diagnosis of dementia and currently on an antipsychotic (n=49), 39 were under GP review only and 10 were under CMHT review.

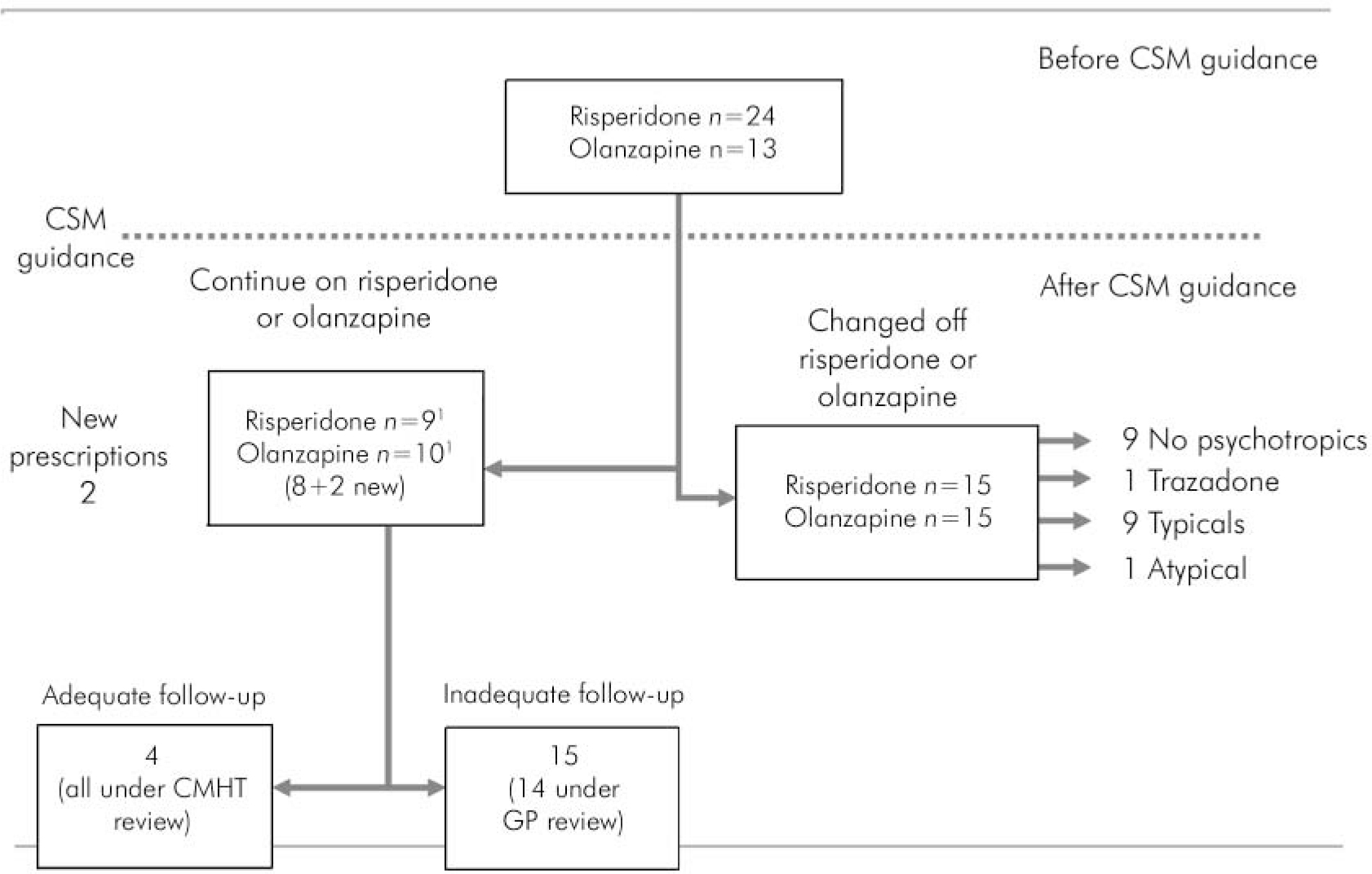

Fig. 1. Outcome for residents who were on risperidone and olanzapine before the Committee on the Safety of Medicines (CSM) guidance. 1. There were attempts to withdraw these medications in 4 of the 9 who continue on risperidone and 2 of the 8 who continue on olanzapine.

The outcome for residents who were on risperidone or olanzapine before the CSM advice is summarised in Fig. 1. Before CSM advice 69% (37 out of 54) of the antipsychotics prescribed to residents with a diagnosis of dementia were either risperidone or olanzapine. This reduced to 39% (19 out of 49) after the CSM advice, and resulted in a significant drop in the atypical to typical antipsychotic ratio, from 3.1:1 before CSM to 1.04:1 after CSM.

Of the 19 who continued on risperidone or olanzapine, the vast majority were under GP review only (15 out of 19). Although there was an attempt to withdraw these antipsychotics in some (n=6), the majority were categorised as receiving inadequate review (15 out of 19). Of the 15 receiving inadequate review, 14 were under GP review only, which is statistically highly significant (P=0.001 Fisher's exact test). Moreover, 13 of the 15 receiving inadequate review were also under review ‘as required’. In comparison, only 1 of the 4 residents who were receiving adequate review (i.e. more frequently than 6 monthly) were seen only as required. This difference again was significant (P=0.037, Fisher's exact test).

Discussion

This study was an examination of current guidelines regarding antipsychotic prescription to patients with dementia, and makes no comment on the appropriateness or otherwise of these guidelines. Recent evidence, from a large retrospective cohort study, does not support the CSM warning that atypical antipsychotics (when prescribed to patients with dementia) are associated with an increased risk of stroke (Reference Gill, Rochon and HerrmannGill et al, 2005). However, in another cohort study, involving 22 890 older patients, those receiving typical antipsychotics compared with atypicals had a significantly higher adjusted risk of death at all three intervals studied (Reference Wang, Schneeweiss and AvornWang et al, 2006).

Whatever the rationale for the CSM guidelines, they have prompted a welcome reconsideration of antipsychotic use in this vulnerable population. It is of concern that 46% of residents with dementia in the care settings examined here are receiving antipsychotics, often without adequate review. It is also concerning that 64% of residents with dementia are being prescribed antipsychotics for behavioural symptoms and not for psychosis. The extent to which CSM guidelines have been followed is patchy. For the majority of residents with dementia who were on risperidone or olanzapine, an attempt at withdrawal was made, but for 30% there was no such attempt. It is noteworthy that the two new prescriptions for olanzapine were for psychosis. In this community sample there was less success in withdrawing antipsychotics compared with specialist practice in a CMHT for older people (details available from authors); for example, only one resident was successfully changed to a different psychotropic drug treatment (trazadone).

Current practice indicates that CMHTs discharge a patient with dementia who is resident in a care facility fairly quickly. Thereafter, almost all of these patients, who are under GP care, are seen as required, with no set review date, or are seen only 6 monthly or less often. It is possible that a patient with dementia who is experiencing side-effects from a prescribed antipsychotic will not be followed up at all, unless there is a concurrent problem requiring GP review. The importance of review of such patients was one of the reasons for the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act 1987 regulations (OBRA 87) in the USA (Reference BurkeBurke, 1991). These regulations set out indications for antipsychotic prescription to residents of nursing homes, including the need to try a non-pharmacological alternative prior to prescription and an enforced gradual dose reduction after 6 months of antipsychotic therapy. Four follow-up studies after OBRA 1987 have consistently demonstrated a decrease of about 30% in antipsychotic prescribing (Reference Furniss, Craig and BurnsFurniss et al, 1998).

Other proven effective strategies aimed at reducing antipsychotic prescriptions in residential settings are educational programmes (on psychopharmacology), pharmacist involvement and non-pharmacological interventions (Reference Furniss, Craig and BurnsFurniss et al, 1998). Further research is needed to clarify what approach would be most acceptable and cost-effective to assist British GPs in the management of this patient population. In the meantime we would encourage the 3 T approach to antipsychotic prescribing as outlined in the Royal College of Psychiatrists guidelines (Royal College of Psychiatrists, 2004b ), namely specified targeted symptoms, titrated doses, and time-limited prescription with a clear date for review and/or an attempt at dose reduction.

Declaration of interest

None.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.