Patient-centred psychiatry depends upon delivering care which is patient focused. Patient-centred care is defined as A key advantage in psychiatry compared with many other medical specialties has been its focus on teamwork for managing patients. Much of the content of Stewart's definition has already been happening in psychiatry, although this may have been patchy.

(Care) which explores the Patients’reasons for their visit, their concerns and need for information, seeks an integrated understanding of the patient's world i.e. their whole person, emotional needs and life issues and finds common ground on what the problem is and mutually agrees on management, enhances prevention and health promotion and enhances the continuing relationship between the patient and the doctor (Reference StewartStewart, 2001)

The six interactive components of the patient-centred process are listed in Box 1.

Box 1. Six interactive components of the patient-centred process. (After Reference Brown, Stewart, Weston, Stewart, Brown and WestonBrown et al, 2003)

|

Characteristics of a good psychiatrist

The core attributes listed in Good Psychiatric Practice (Royal College of Psychiatrists, 2004) are: clinical competence, being a good communicator and listener, being sensitive to gender, ethnicity and culture, commitment to equality and working with diversity, having a basic understanding of group dynamics, being able to facilitate a positive atmosphere within a team, ability to be decisive, ability to appraise staff, basic understanding of operational management, understanding and acknowledging the role and status of vulnerable patients, bringing empathy, encouragement and hope to patients and carers, critical self awareness of emotional responses to clinical situations, being aware of potentially destructive influence in power relationships and acknowledging situations where there is potential for bullying.

A comparison between the components of Box 1 and the attributes of a good psychiatrist indicates a tremendous area of overlap in the qualities of an individual as well as the characteristics of a service which will be acceptable to patients and their carers.

As the consultant of the future will have to have a range of competencies in clinical management, teaching, research and other areas, the training of such individuals will have to take on board a number of parameters which will include peer group based learning, learning across disciplines and teams, and continuing professional development.

Current developments in postgraduate medical education

A number of major changes are taking place in postgraduate medical education. In fact, the scale of changes is almost certainly unprecedented, and it is likely that they will need to be put into practice fairly rapidly. This is because they will be required or affected by legislation that will come into force in 2005.

Five main driving forces are:

-

1. The Postgraduate Medical Education and Training Board (PMETB) and its Principles and Standards for an Assessment System for Postgraduate Medical Training (Reference Southgate and GrantSouthgate & Grant, 2003).

-

2. Towards Excellence in Assessment in Medicine: A Commitment To a Set of Guiding Principles (Reference DonaldsonDonaldson, 2004) sets out 15 principles along similar lines to the PMETB document, and the Royal College of Psychiatrists has indicated a commitment to adopting these.

-

3. Modernising Medical Careers (Department of Health, 2000) (see also GMC, 1993; Reference Brown and BhugraBrown & Bhugra, 2005a).

-

4. The European Working Time Directive (EWTD) and Implementing the European Working Time Directive: Guidance from the Academy of Medical Royal Colleges (Academy of Medical Royal Colleges, 2004) (see also Reference Brown and BhugraBrown & Bhugra, 2005b).

-

5. The Royal College of Psychiatrists’ commitment to involving patients and carers throughout specialist education in psychiatry.

The way forward

Following detailed and extensive discussions at the Court of Electors it was agreed that the following options should be discussed and debated more widely:

-

1. Combine senior house officer (SHO) and specialist registrar (SpR) training as a 5-year long programme based on competency training and assessment. The trainees will get their national training number (NTN) and retain it throughout basic training and higher training. The advantages this would bring include better recruitment, better retention, structured training and a sense of continuing advancement and achievement. Disadvantages include committing to training for 5 years, although in theory this period could be shorter for those who reach the required level of competency earlier. This option might need an earlier MRCPsych Part I to screen for suitable candidates and a later MRCPsych Part II, perhaps at the end of year 4, with continuing modular assessments.

-

2. Another option is to keep the training separate, and take examinations at the current stages of training. This means that the overall training would be 5 years with MRCPsych Part I at 12 months and Part II at 30 months. This will cause the least disruption for the examinations department and candidates, but among the disadvantages are that examinations would remain the focus of training rather than the training itself.

-

3. Maintain status quo with no change. This is not a realistic option.

Assessment in psychiatric training

Assessment and the Postgraduate Medical Education and Training Board

It is possible that the PMETB might propose a common examination across all the Medical Royal Colleges. It is likely that initially they will ‘start where we are’. Nevertheless, we need to think about the content and timing of MRCPsych Part I and be prepared to make changes reasonably swiftly if necessary. One option is shown in Box 2.

Box 2. One option for content and timing of assessment

| After 6-9 months of starting psychiatry: | |

| MRCPsych I | Objective structured clinical examination (OSCE) + knowledge-based assessment |

| After 4 years: | |

| MRCPsych II | OSCE+modular assessment |

Modular assessments

Modular assessments could be appropriate in the following areas: child and adolescent psychiatry; learning difficulty; forensic psychiatry; psychiatry of old age; and substance abuse. It could be that a proportion of the marks for the MRCPsych II should come from modular and place of work assessments (PWA). Modular assessments could include theoretical examinations conducted locally, but with standards monitored and maintained centrally. These might be held perhaps once a year, but the resource implications for the examinations department could be immense.

Workplace-based assessments

It seems likely that the PMETB will place considerable importance on workplace-based assessment as they have constituted a special subcommittee for this specific purpose.

There are several options under consideration for workplace-based assessments:

-

1. Assessing the trainee's letters to the GP and referral letters to other agencies.

-

2. Observing the trainee interviewing a patient.

-

3. Observing the trainee presenting cases to the team members/consultant on the telephone.

-

4. Observing the trainee giving information to carers.

There is also a well-developed workplace-based assessment method called mini-CEx that is likely to be appropriate for this purpose.

Postgraduate Medical Education and Training Board principles of assessment and standards

The PMETB has repeatedly emphasised that assessments must be based, not on the factual recall of knowledge, but on competency (what the doctor can do) and performance (what the doctor does do). This is why workplace-based assessment is likely to be so important and the emphasis on traditional written examinations will decrease.

The PMETB has set out 9 governing principles for assessment — these are illustrated in Box 3.

Box 3. The PMETB 9 governing principles for assessment

|

Training models

In view of the two foundation years (Modernising Medical Careers) it is our intention that all trainees have a minimum 5-year training in psychiatry. The psychiatry training in foundation years will not be counted towards postgraduate training, nor are they expected to be in any other specialty.

The foundation year 2 and its contents and any assessment at the end of it is not dealt with in this paper (see Reference Brown and BhugraBrown & Bhugra, 2005a).

Entry criteria for postgraduate training in psychiatry will remain the same.

We need to consider the possibility of MRCPsych Part I as a suitable screen for entry into the speciality and for sitting the examination within 6-9 months of starting the training. The assessments will have to be competency-based.

Exit criteria are almost certain to include a satisfactory record of workplace-based assessment, probably supplemented by modular assessments, a competency-based examination towards the end of year 4, along with Record of In-training Assessment Form G award.

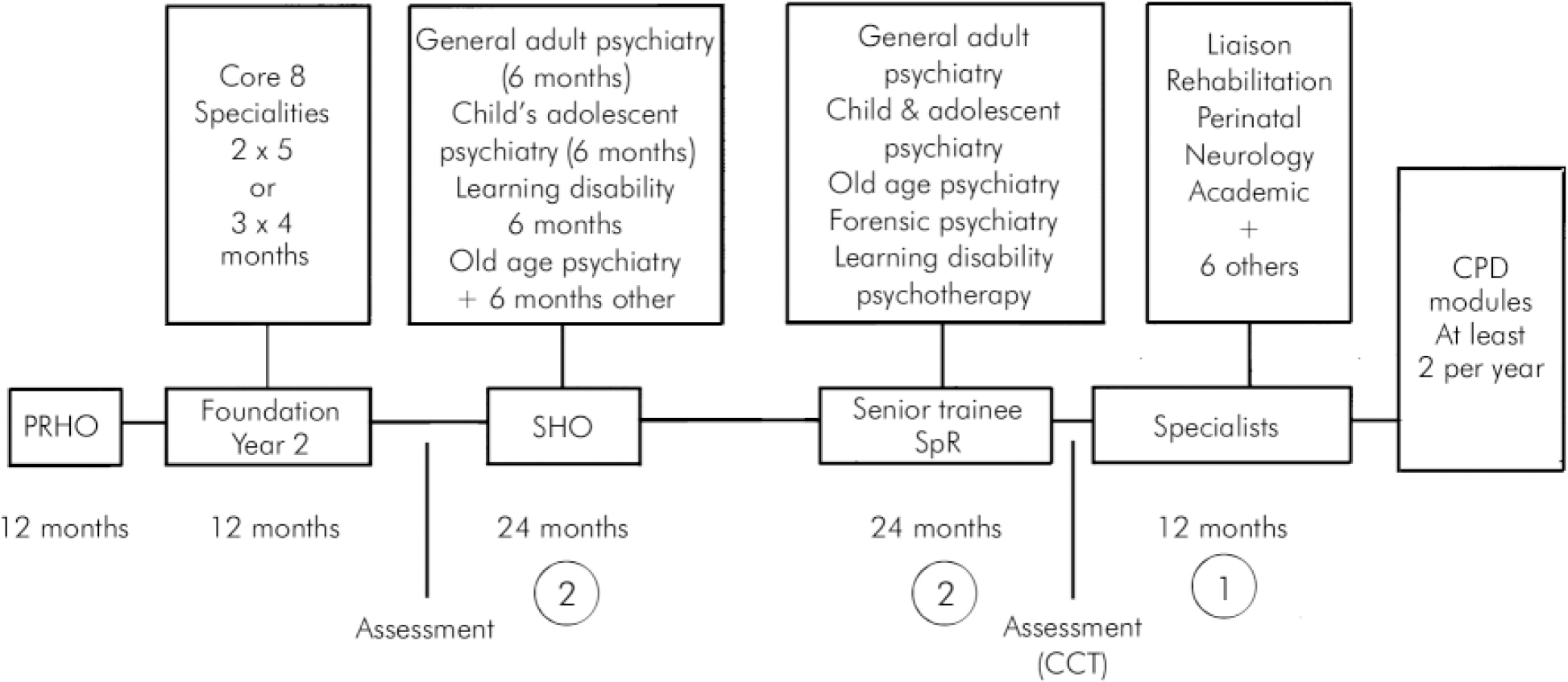

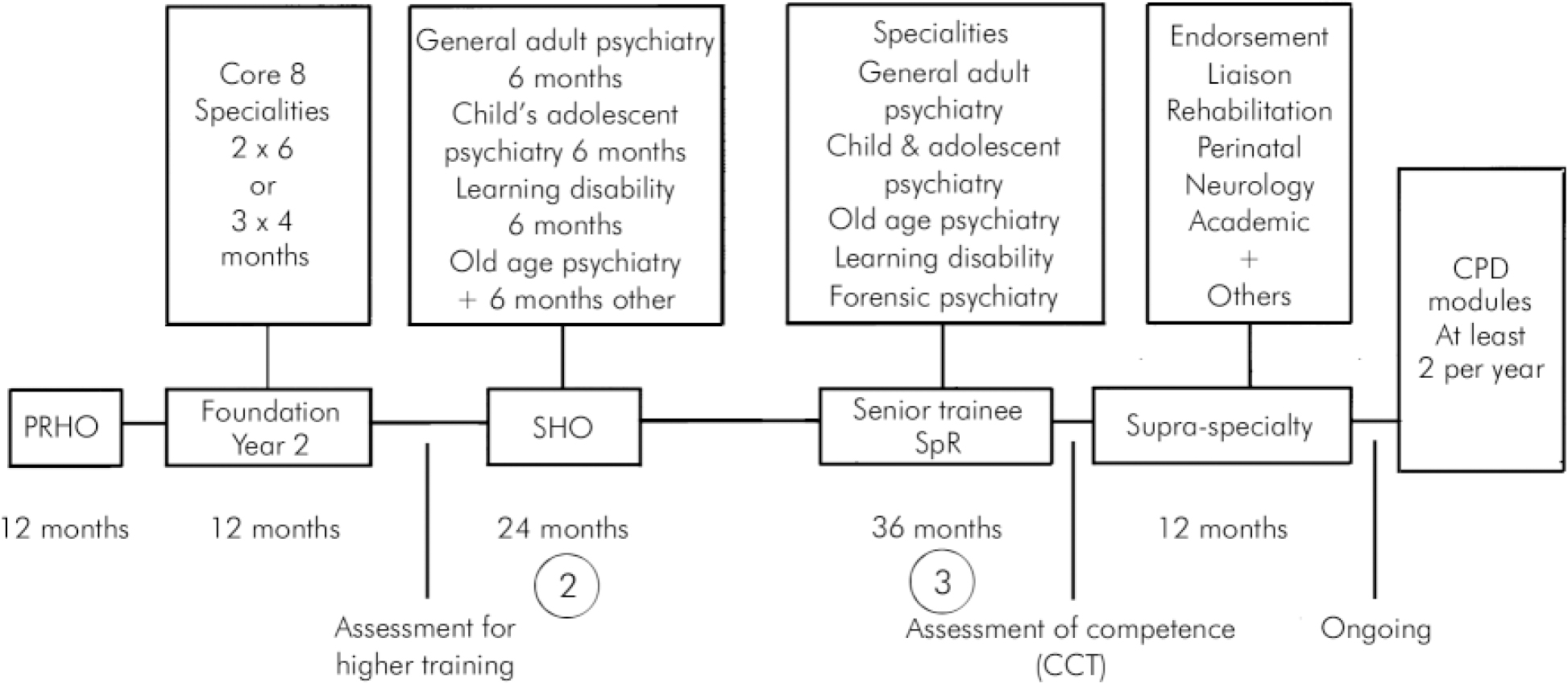

Two possible models of training are illustrated in Figs 1 and 2.

Fig. 1. Proposal for a ‘2 + 2 + 1’ model of training.

Fig. 2. Proposal for a ‘2 + 3’ model of training.

Sub-specialist training

After the CCT, trainees could choose to super-specialise in various areas. These could include academic psychiatry, for example, or a combination of more than one super-speciality such as forensic psychotherapy.

Some guidelines for super-specialist training are listed below.

-

• Training and need-assessment to be modular.

-

• A national workforce coordination will be essential and the Royal College of Psychiatrists will take the lead.

-

• Selection after foundation year 2 will be competitive but in both models 5-year training will be the norm.

-

• Funding of posts will be through the deaneries.

-

• Curriculum and competencies will be referred to the Specialist Training Authority (initially) and to the PMETB.

-

• The assessments will be transparent and the Royal College of Psychiatrists will guarantee standard setting and quality assurance.

-

• Exit will be competency-based and a single CCT may be offered as suggested by PMETB.

-

• Flexible training will follow the same competency-based assessments.

Table 1 illustrates the roles and methods of learning.

Table 1. Roles and methods of learning

| Role | Learning | ‘ Bedside’ teaching | Structured teaching | Workshops |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medical expert | Self-directed | Apprenticeship model | Problem-based learning | Effective consultation |

| Individual mentoring | Clinical reasoning | Presentation skills | ||

| Evidence-based medicine | ||||

| Information Technology | ||||

| Bioethics | ||||

| Communicator | Empathy | Role models in effective communication | Conceptual frame skills in communication | Role playing |

| Respect | Video + | |||

| Individual and group | Racial/cultural | |||

| Reflection of experiences | ||||

| Collaborator | Interdisciplinary organisation | Role modelling | Governance structures | Team-building |

| Seamless healthcare delivery | ||||

| Manager | Managing time, teams and structures | Role modelling | Allication of resources | Practice management |

| Shadowing | ||||

| Leadership skills | ||||

| Health advocate | Individual patient and patient population issues | Modelling | Multidisciplinary teaching | Effective intervention and assistance |

| Scholar | Self-directed | Modelling | Clinical standard setting | Critical appraising |

| Evidence base | Quality assurance | |||

| Lifelong learning | Quality management | |||

| Practice reflection | Health economics | |||

| Professional | Direct observation feedback | Modelling | Case-based discussion | Awareness of professional responsibilities |

| Medicolegal | ||||

| Medical ethics |

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.