The issue of services for individuals with severe personality disorder (SPD) is taxing policy-makers (The Times, 31 October 1998) as much as clinicians (Reference CopeCope, 1993). Although the prevalence of SPD is high both within criminal justice (Reference Singleton, Meltzer and GatwardSingleton et al, 1998) and forensic health care settings (Reference Taylor, Leese and WilliamsTaylor et al, 1998), there is a lack of consensus regarding treatment or services required, underpinned by inadequate research knowledge and assessment procedures (Reference Dolan and CoidDolan & Coid, 1993).

Within England, Wales and Scotland, individuals with SPD are treated in various in-patient settings including the special hospitals, regional secure units, specialist learning disability units, other NHS or private hospitals and in specialist prison units. A Home Office-Department of Health working party recently published proposals for policy development, Managing Dangerous People with Severe Personality Disorder (Home Office & Department of Health, 1999) considering future policy on legal and service provision for individuals with SPD. The strategy for SPD services in England and Wales is at a crossroads, with consideration being given to a ‘third way’, similar to suggestions made in the Ashworth Inquiry (Reference Fallon, Bluglass and EdwardsFallon et al, 1999), where individuals (particularly offenders) with SPD could be assessed and possibly receive treatment within small, high-secure hospital and prison units, using agreed assessment and treatment protocols.

While recommendations of special units to treat SPD may be relatively new, the use of standardised assessments was suggested by the Working Group on Psychopathic Disorder five years ago (Reference ReedReed, 1994). It argued that assessment of personality disorder should “promote the adoption of multi-method criteria for categorising severe personality disorders” including one or more of the following :

-

(a) ICD-10 (World Health Organization, 1992) or DSM-IV (American Psychiatric Association, 1994) Axis II categorisation (from structured interview) ;

-

(b) Hare's Psychopathy Checklist, revised (PCL-R) (Reference HareHare, 1991)

-

(c) Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (MMPI) profiles (Reference Dahlstrom, Welsh and DahlstromDahlstrom et al, 1975) ;

-

(d) Psychodynamic formulation.

Reed's findings regarding assessment have been endorsed by a Royal College of Psychiatrists' report on SPD (Royal College of Psychiatrists, 1999). However, another report (for the High Security Psychiatric Services Commissioning Board) on diagnostic and assessment criteria in SPD (Reference Meux and McDonaldMeux & McDonald, 1998) acknowledged that current assessment methods remain inadequate and recommended establishing research projects to develop customised assessment tools, neurocognitive instruments and outcome measures. Adopting assessment protocols that assume congruence between individual health care units and specialist prison services would be an important starting point. Such information would also “promote a greater consistency among future clinical and research studies” (Reference ReedReed, 1994).

Until recently there had been no attempt to examine how individuals with SPD are assessed within various settings. Storey et al (Reference Storey, Logue and Watkins1998) surveyed 250 hospital and penal establishments where individuals with SPD are managed. Their conclusions were limited by a low response rate (39%), but suggested that only half (10/21) of the hospital settings and less than one-fifth (5/29) of the penal settings that responded used a known rating instrument to assess personality structure.

Therefore, the questions to be answered by this study were :

-

(a) How do specialist in-patient forensic health care and prison services in England, Wales and Scotland formally assess SPD ?

-

(b) How does the assessment procedure compare with the Reed (Reference Reed1994) recommendations ?

The study

A letter requesting “details of any assessment procedure you might run for newly admitted patients or prisoners with personality disorder” was sent to 50 services in September 1997, with follow-up letters or telephone requests in January 1998 and June 1998. Forty-Five mental health services were identified from the Directory of Forensic Facilities in the UK (Rampton Hospital Social Work Department, 1996) : four maximum security (special) hospitals (particularly the wards within the hospital treating SPD) ; 30 regional/interim secure units (including one adolescent forensic service) ; seven other hospitals (private units and therapeutic communities) ; and four secure specialist learning disability units. Six services were in the private/independent sector.

Five prison units known as specialising in the assessment and treatment of SPD prisoners were also contacted.

Findings

Thirty-five units responded (70%) : three (75.0%) special hospitals ; 22 (73.3%) regional secure units, three (75.0%) learning disability units ; three (60.0%) prison units ; and four (57.1%) other NHS hospitals. Three regional secure units and one learning diability service (11.4%) reported that they never or rarely admitted patients with Axis II disorders alone. Twenty-one (60.0%) services reported that they had no formal procedure for assessing SPD although all but one unit said that they employed an unstructured clinical interview which included some assessment of personality. Almost one-quarter stated that their assessment was multi-disciplinary (71.4% of services).

Fourteen services (40%) reported having a formal personality assessment. Seven were regional secure units (31.8% of the regional secure units who responded), two (66.7%) were within special hospital facilities, three (75.0%) were other hospitals, two (66.7%) were specialist prison units but none were learning disability services. In addition, two regional secure units and one learning disability unit used rating instruments routinely but did not regard this as a formal procedure.

Respondents were asked what type of procedure they employed in their assessment of SPD. The results are shown in Table 1. The types of instruments were grouped as Axis II ICD/DSM diagnostic (e.g. International Personality Disorder Examination (IPDE) ; Reference Loranger, Sartorious and AndreoliLoranger et al, 1994), non-diagnostic personality assessment (e.g. Millon Clinical Multiaxial Inventory (MCMI) ; Reference Millon, Davis and MillonMillon et al, 1997), symptom severity (e.g. General Health Questionnaire ; Reference GoldbergGoldberg, 1981), any neuropsychological investigations or specific behaviour and attitudinal measures (e.g. anger ; Reference NovacoNovaco, 1975). Two units (5.7%), both regional secure units, said they routinely developed a psychodynamic formulation as part of their assessment. Nine (25.7%) providers were, therefore, providing at least one of the recommended assessment tools suggested by the Reed Report (Reference ReedReed, 1994).

Table 1 Type of routine instruments employed in assessment procedure

| Instrument type | Special hospital personality disorder unit (n=3) Number (%) |

Regional secure unit (n=22) Number (%) |

Learning disability unit (n=3) Number (%) |

Other hospital (n=4) Number (%) |

Prison unit (n=3) Number (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Axis 2 diagnostic | 1 (33.3) | 2 (9.1) | 0 | 0 | 1 (33.3) |

| Personality assessment | 2 (66.7) | 8 (36.4) | 0 | 1 (25.0) | 2 (66.7) |

| Symptom severity | 1 (33.3) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (33.3) |

| Neuropsychological | 1 (33.3) | 3 (13.6) | 1 (33.3) | 0 | 1 (33.3) |

| Specific behaviour/attitudes | 2 (66.7) | 1 (4.5) | 1 (33.3) | 0 | 1 (33.3) |

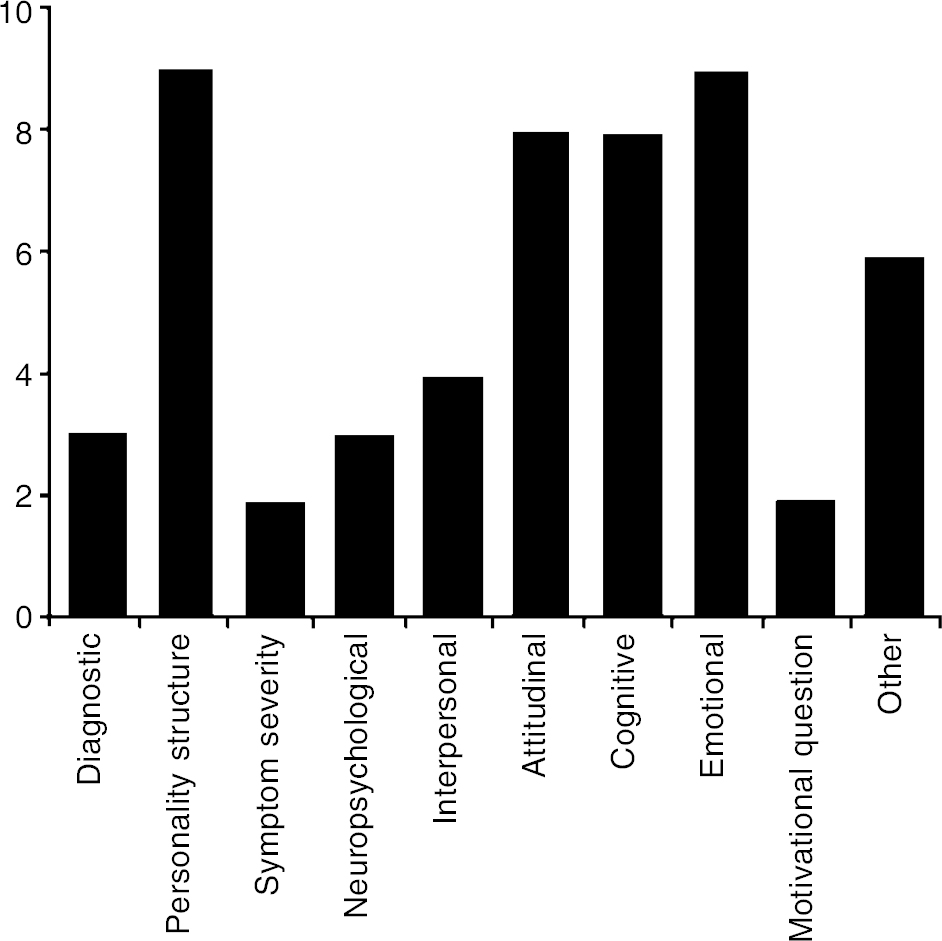

The type of assessment instruments is shown in Fig 1. For the purpose of categorisation, rating instruments measuring specific behaviour, attitudes, emotion or styles of thinking are shown separately.

Fig. 1. Types of assessment instruments

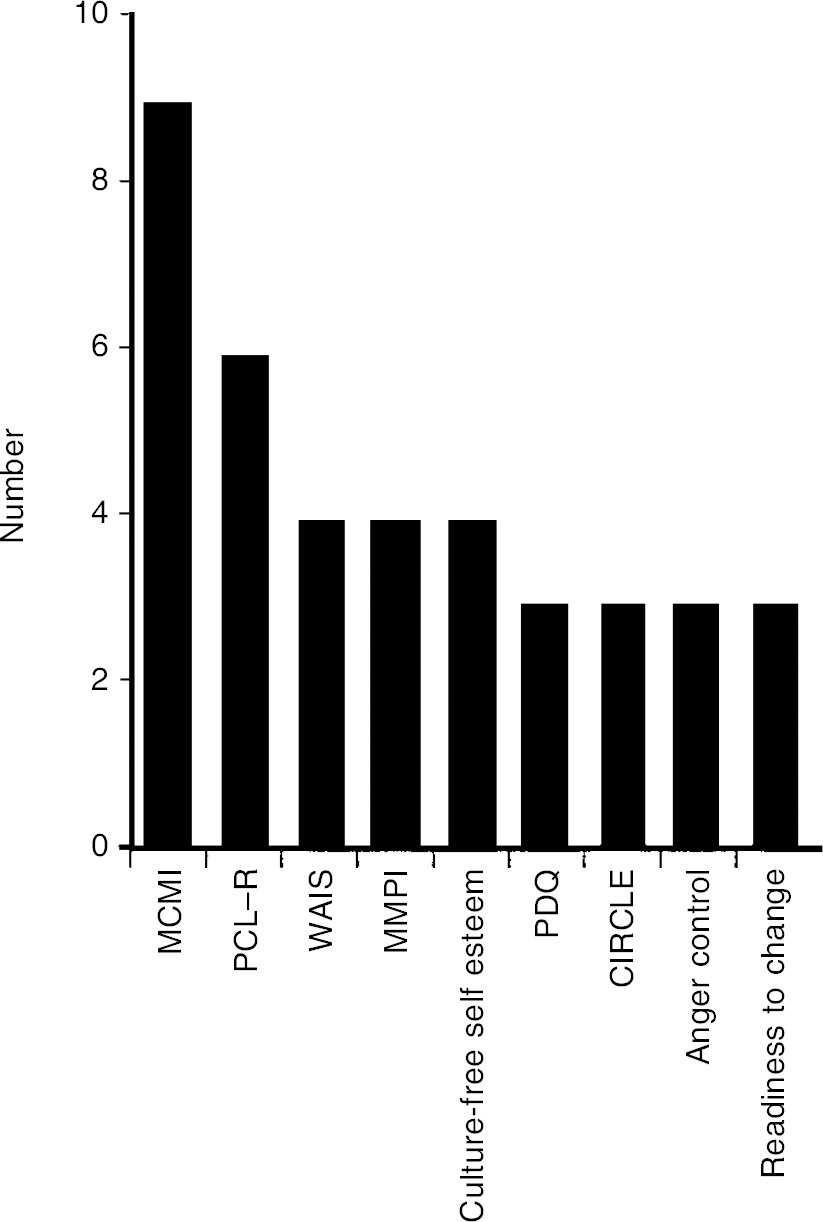

Fifty-four different rating instruments were employed routinely. The most frequently used (by three services or more) are shown in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2. Most frequently employed assessments in routine use. MCMI, Millon Clinical Multiaxial Inventory (Reference Millon, Davis and MillonMillon et al, 1997) ; PCL-R, Psychopathy Check-list—revised (Reference HareHare, 1991) ; WAIS, Wechsler Adult Intelligence Schedule (Reference WechslerWechsler, 1981) ; MMPI, Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory profiles (Reference Dahlstrom, Welsh and DahlstromDahlstrom et al, 1975) ; Culture-free Self-Esteem Inventory (Reference BattleBattle, 1992) ; PDQ, Personality Diagnostic Questionnaire (Reference HylerHyler, 1994) ; CIRCLE, Chart of Interpersonal Reactions in Closed Living Environments (Reference Blackburn and RenwickBlackburn & Renwick, 1996) ; Anger Control (Reference NovacoNovaco, 1975) ; Readiness to change (Reference Rollnick, Heather and GoldRollnick et al, 1992).

Discussion

Although this survey replicates aspects of a previous survey of settings where individuals with SPD are managed (Reference Storey, Logue and WatkinsStorey et al, 1998), its findings are strengthened by an improved response. However, any conclusions are limited by the small numbers of some types of unit and the unsystematised selection of prison units. Further, absolute numbers of admissions of individuals with SPD to particular units was not collected and therefore equal weight has been given to responses whether a service admits many or few individuals with SPD.

Two conclusions suggested by the findings are that first, personality disorder is not formally assessed by the majority of forensic units who may admit individuals with SPD ; and second, even when formal assessment occurs, it may be inadequate or lacking in fundamental areas. Taking the elements of the assessment recommended by Reed (Reference Reed1994) and standard (structured interview for diagnosis, PCL-R, MMPI-type profile and psychodynamic formulation), only one unit (a regional secure unit) provided this though a quarter of all units had adopted some aspect of the recommended assessment procedure. Such findings will not be surprising to most clinicians and have been acknowledged for some time (Reference Dolan and CoidDolan & Coid, 1993 ; Reference Meux and McDonaldMeux & McDonald, 1998).

What is striking is the range of instruments used to assess SPD, both in terms of the absolute number of different ratings (n=54) and the variety, from three different assessments for diagnosis to nine different non-diagnostic ratings of personality structure. The numerous tools for assessing emotional states or attitudes is possibly understandable considering the wide range of target affects or attitudes, though the paucity of interpersonal ratings is surprising given the nature of SPD.

However, four different instruments were used to assess anger/hostility and three for impulsivity. This diversity may reflect assessors' preference in addition to the occasional requirement for specific measures. Nonetheless, there is overlap between some instruments and therefore scope for adopting standard assessments allowing comparison between units or settings for an individual over time.

Despite the large number of different instruments, only nine tools were used by three units or more. The popularity of self-report instruments, such as the MCMI (Reference Millon, Davis and MillonMillon et al, 1997) or the Personality Diagnostic Questionnaire (PDQ) (Reference HylerHyler, 1994), at the apparent expense of other structured clinical assessment instruments (Structure Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID-II) ; Reference First, Spitzer and GibbonFirst et al, 1995 ; or the IPDE ; Reference Loranger, Sartorious and AndreoliLoranger et al, 1994) is concerning, especially since underreporting or overreporting of Axis II psychopathology is a known problem associated with self-report instruments (Reference Hunt and AndrewsHunt & Andrews, 1992). The Royal College of Psychiatrists (1999) recently warned against the use of self-report ratings for making personality disorder diagnoses, though accepted their role in screening. The adoption of the PCL-R (Reference HareHare, 1991) as a useful assessment of psychopathy within forensic settings probably reflects its clinical utility, particularly as an apparent predictor of recidivism.

In conclusion, two proposals should be considered. First, structured (non-self-rated) diagnostic assessment of Axis II psychopathology should be employed as a prerequisite to other dimensional assessments of personality structure. Second, it is time for a moratorium on the use of so many differing assessments of behaviour, affect, cognitive and attitudinal styles of individuals with SPD in favour of a first-line, nationally agreed, focused repertoire of instruments. Such suggestions will require compromise but only then can individuals with SPD be evaluated with the “greater consistency” that Reed (Reference Reed1994) desired.

Acknowledgements

The study was partly supported by a Peter Scott Memorial Scholarship in Forensic Psychiatry from the Royal College of Psychiatrists. I wish to thank all the respondents who took the time to write or speak by telephone. A version of this paper was provided as a report to the High Security Psychiatric Services Commissioning Board.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.