The high-security hospitals are undergoing a retraction process. In conjunction with this, regional services are being developed for those patients who require longer-term treatment at medium-security units.

The retraction of the high-security hospitals has widespread implications for mental health services and the criminal justice system. This paper aims to provide an overview of the issues involved, along with the background against which these changes are taking place and the uncertainties involved in the process.

It has long been acknowledged that many patients in the three high-security psychiatric hospitals (Ashworth, Broadmoor and Rampton) no longer need the level of security provided (Department of Health, 2000). It has been national strategy for a number of years to provide alternative services for these patients (Reference ReedReed, 1997; Department of Health, 1999). Regional plans to develop alternative secure services for in-patients in the high-security hospitals who no longer require high security (Reference Shaw, Mckenna and SnowdenShaw et al, 1994) are at varying stages of implementation. These services are predominantly longer-term medium-secure services with some low-security provision according to local needs (Reference Taylor, Maden and JonesTaylor et al, 1996). The National Oversight Group, the Department of Health body that oversees the high-security services, commissioned a review to model the strategic change in the high-security hospitals and its impact upon the regions of England and Wales (Reference FenderFender, 2003). This current paper will use the information available from the Fender reports and other evidence to examine potential implications of the major changes that are underway in the high-security hospitals.

Predicting the size of the high-security hospitals

The Fender report (2000) analysed data from the high-security hospitals and regional plans to develop alternative secure services to produce a systems model of the change process. This model included predictions of changes in bed numbers within the high-security hospitals and revenue implications of the changes. Overall numbers are predicted to fall from 1276 to around 771 between 2000 and 2005, but an additional 140 beds will be commissioned as part of the dangerous and severe personality disorder (DSPD) initiative.

The projected changes in bed numbers in the Fender report (2000) are ambitious, even when an accelerated discharge process is being actively undertaken. Bed number projections took into account regional plans, including those that only existed in outline and for which funding was not yet identified. Fender (Reference Fender2000) made assumptions that the number of people with learning disability could fall to the lowest current regional level (from 95 to 55), and that the number of women would be no more than a quarter of present levels (a fall from 195 to 50), again with an element of comparison with low regional levels. Beds for men with mental illness and personality disorder (excluding DSPD) are expected to fall from 986 to 666. It is worth noting that for the smaller groups within high-security hospitals (women, individuals with learning disability and men with personality disorder), there is limited understanding of the regional variations and pathways that lead to admission to high-security units. It is difficult to support the assumption that the lowest regional numbers (for women and individuals with learning disability) can be achieved by all regions in the absence of more substantial evidence.

Fender (Reference Fender2000) also stated that no firm assessment of level of unmet need among prisoners could be made, and constructed a simple model to predict the impact of variable rates of admission into the high-security hospitals from prison. Other potential influences on demand for high-security admissions, which are difficult to quantify, were not included in the projections.

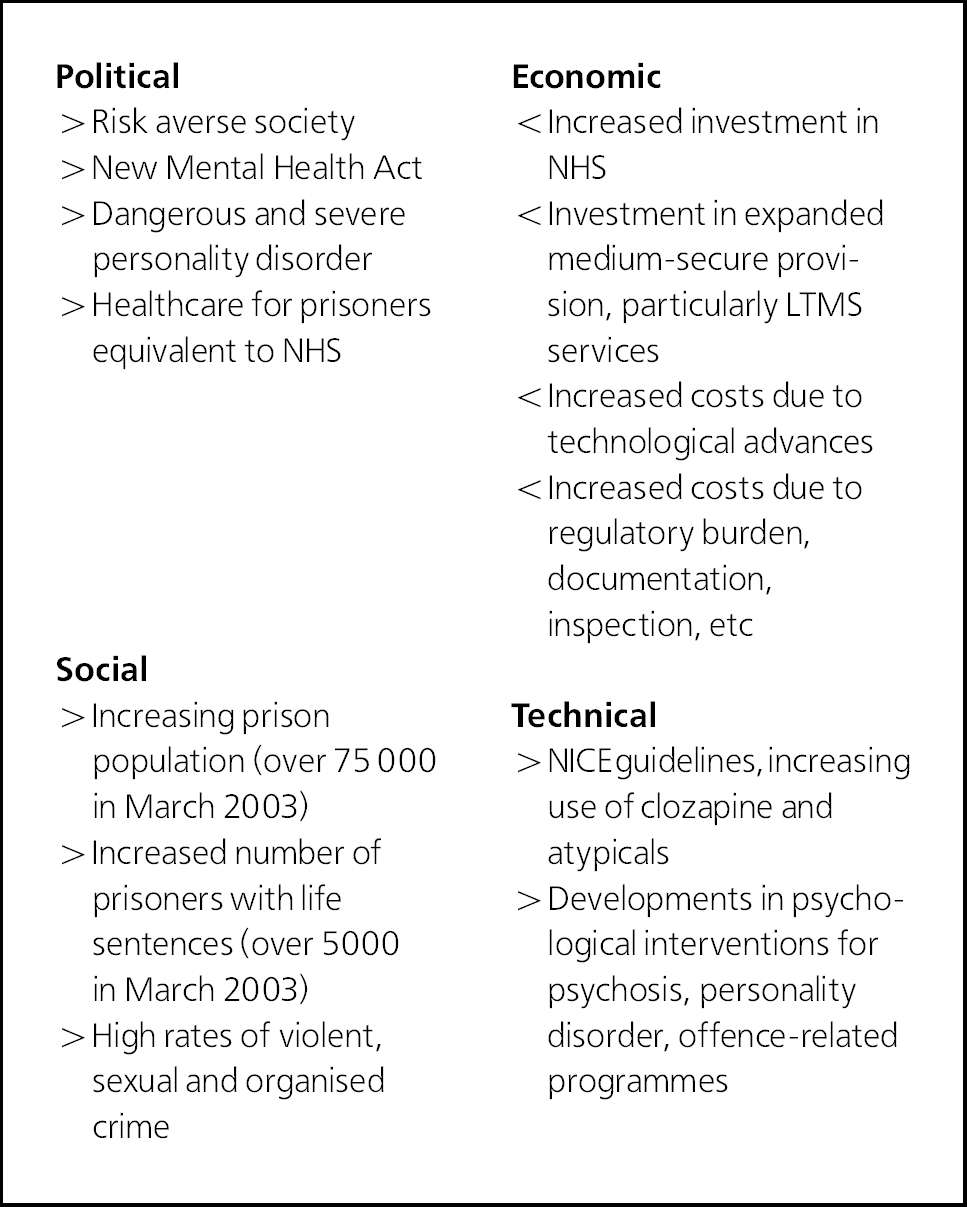

There are many potential influences on admission to high-security hospitals. Some can be illustrated using the framework of political, economic, social and technical (PEST) analysis as shown in Fig. 1 (Reference Johnson and ScholesJohnson & Scholes, 1997).

Unmet need in prison is potentially the major determinant of demand for high security. The available research evidence, as reviewed by Gunn & Maden (Reference Gunn and Maden1998), predicted that if the unmet need in prison was to be addressed there would be no reduction in bed number requirements in high-security units. The prison population is increasing (Reference Hollis and CrossHollis & Cross, 2003); this includes a large increase in the number of prisoners with life sentences. Major changes are taking place in prison healthcare that will impact upon the demand for beds in both medium-and high-security units. These include the screening programme for the DSPD pilot schemes and the transfer of responsibility for prison healthcare to the National Health Service. There is already evidence that the DSPD screening programme is identifying more individuals with mental illness in high-security (category A) prisons and the number of individuals with mental illness in prison may be increasing in line with an expanding prison population. If prisoners are really to receive equivalent health-care to the general population, given the increasing availability of pharmacological and psychological interventions for psychosis and interventions for personality disorder, the implications of this aspiration are potentially massive.

Fig. 1. Potential influences on admission to high-security hospitals as illustrated by the political, economic, social and technical (PEST) analysis. >, increasing demand; <, decreasing demand; NHS, National Health Service; LTMS, longer-term medium-secure; NICE, National Institute for Clinical Excellence.

The impact upon the prison sector of inadequate numbers of high-security beds is likely to be serious. The high-security hospitals provide treatment for the most challenging and complex minority of prisoners transferred into the healthcare system. Already there are waiting lists for some of the high-security hospitals and anecdotal evidence that the level of challenging behaviour and comorbid personality disorder among those transferred from prison to high-security units is increasing compared with 5 years ago (Reference Collins and EvansCollins & Evans, 2000). Between 1999 and 2003 the proportion of admissions to the male mental illness service at Rampton from category A prisons increased from 34 to 48% and the proportion of those under 35 increased from 45 to 66% (Davies, personal communication, 2004). This may have an impact upon the projected length of stay. As length of stay is a very important determinant of bed requirements in services, this possible change in morbidity pattern in new referrals to the high-security hospitals may have a big impact upon overall bed requirements in the future.

The Fender report (2000) systems model took no account of the potential for the new longer-term medium-secure services to become a source of referral to high-security units in the future. The assumption that these new services would not need to refer patients to high-security units on occasions does not fit with the evidence for two-way flow between medium- and high-security services. Also, within the high-security hospitals there is a significant transfer between lower-dependency wards (caring for many patients identified as requiring longer-term medium-secure care) and higher-dependency wards, depending on variations in levels of challenging behaviour. It seems reasonable to assume such variability in presentation and perceived level of risk may continue to occur in the future.

It may be seen that the Fender (Reference Fender2000) projections were based on optimistic planning assumptions across a range of factors. The overall conclusion that bed numbers in high-security units would reduce by 38% (1290 in March 2000 to 771 by 2005) is ambitious in terms of bed number reductions and timescale. It may well be achievable but at a cost to other health and criminal justice services. The level of support the high-security services currently provide for the medium-secure services (both the National Health Service and the private sector) would be reduced, resulting in these services having to provide care for a more challenging client group on a longer-term basis. In turn, this may impact upon the ability of the medium-secure services to support general mental health services in the treatment of their high-risk, more challenging patients who require secure care.

The high-security hospitals provide an important safety net for the mental health and criminal justice systems and there will be far-reaching consequences of inadequate provision in this sector.

Development of regional longer-term secure services

New services for patients currently inappropriately placed in high-security hospitals need to take into account the needs of this population. There is evidence that the group identified as needing longer-term medium-secure care is difficult to distinguish from the high-security population (Reference Maden, Curle and MeuxMaden et al, 1995). High-security patients have different characteristics from those currently receiving care in medium-secure units (Reference Coid and KahtanCoid & Kahtan, 2000). Those needing longer-term medium-secure care have more similarities to the high-security population in terms of treatment-resistant mental illness, comorbid personality disorder and offending histories. It is important that new service developments reflect these needs and are not modelled too closely on current medium-secure provision. The Special Hospital Service Authority (1995) identified the longer-term medium-secure group as being challenging to manage on a longer-term basis, requiring perimeter security, space and facilities for an acceptable quality of life. There are particular difficulties for low morbidity catchment areas, which may not have a critical mass to develop a comprehensive service. This problem applies to men with mental illness, who are the largest group identified as requiring longer-term secure care. However, it is a greater problem for smaller patient groups such as women, older people, those with brain injury and men with personality disorder, for whom regional services may not be viable.

The provision of specialist services at supra-regional level appears to be a sensible option for these groups, yet there is little evidence that collaboration across regions is currently taking place to plan new services. Services for women who require enhanced medium-secure provision are a case in point. In September 2002, a closing date for March 2004 was set for Ashworth Women's Service. At the time that the closure date was set none of the patients within the service was identified as requiring high security and a number had no identified regional provision available within the given timescale for closure (Davenport, personal communication, 2004). The service closed in December 2003, and one-third of these women patients have been transferred by default to the women's high-security service in Rampton Hospital. Not only are these patients cared for at a level of security that is higher than they are deemed to require, some are also further from their home area in contravention of Reed Principles (Department of Health & Home Office, 1992).

The needs of catchment areas with small patient numbers appear to have been neglected when the decision was taken to set a closure date for Ashworth Women's Service. Some regions had such small numbers of women requiring enhanced medium security that they have been unable to provide a viable local service. There remains a real risk that, rather than the placement of women in Rampton being a temporary measure, these women patients may remain in Rampton on a long-term basis. There is little evidence that clinically informed specialist commissioning for these smaller groups who need secure provision has taken place. Individual initiatives for London and adjoining regions are ongoing in 2005 and a small project for women based upon point prevalence only has been commissioned for the North West of England. The needs of women who require therapeutically enhanced medium security in some other parts of England and Wales do not appear to have been considered.

The impact of inadequate mental health service planning for women who need secure care will also be felt by those women with urgent mental health needs in prison. The group of women described as having borderline personality disorders, many of whom demonstrate significant levels of psychosis, challenging behaviour and self-harm, is particularly likely to fall into this category, presenting major challenges to the prison service. This group has not been traditionally served by mainstream medium-secure units and were the main target group identified as requiring therapeutically enhanced medium-secure services. It seems likely that women patients will be inappropriately placed in high security and some with urgent mental health needs will remain in prison.

Potential impact of new developments on local mental health services

The new secure services being developed at regional level are staff intensive and expensive. There is a risk that the manpower needs across all disciplines will have a negative impact upon other parts of mental health services which may already be struggling to recruit and retain staff. There is a risk that resources may be diverted from other services to subsidise these expensive new developments. This has happened already with some other aspects of the National Plan (Department of Health, 2001) such as the development of assertive community treatment teams. There is anecdotal evidence in some areas of the country that rehabilitation services, particularly low-secure units, have been diverted to the secure services reconfiguration agenda (L. Behenna & D. Mountain, personal communication, 2004). The detrimental effect upon the local mental health services, which these units currently support, is inevitable.

The national picture described by Fender (Reference Fender2000) is almost exclusively focused upon the development of secure beds. These bedded-units need to be supported by robust community services (including 24-h nursed settings) if they are not to become rapidly bed blocked. Again in the absence of new community provision, there may be increased demand upon already overstretched existing community resources to provide care for this new longer-term secure in-patient population when these patients are ready to move on from in-patient care.

It is essential that services are developed in such a way as to reflect the fact that they form a dynamic system rather than isolated secure in-patient units. If this is not acknowledged there is a risk that services will be developed for the current high-security ‘reprovision’ population but that the system will not meet the needs of new cohorts of service users in the future.

Timescale and revenue issues

The retraction and reprovision of the large area mental hospitals are both much slower and more expensive than was predicted (Reference AbbottAbbott, 2002).

Timescales which have been set for high-security reprovision are ambitious and slippage has already occurred in some schemes. Funding remains unconfirmed for some new developments and the assumptions concerning the level of funding which may be withdrawn from the high-security hospitals are overoptimistic. They take no account of the financial implications of changes in the high-security hospitals that will be necessary to make them safe when the vast majority of their in-patients really need to be there (e.g. the increasing proportion of admissions from category A prisons).

The Fender (Reference Fender2000) projections for revenue release from Ashworth and Rampton Hospitals were based upon per capita reductions and take no account of the increase in acuity and need for bed numbers to be reduced in the high-security hospitals, which may have up to 25 beds per ward. These changes are essential if the high-security hospitals are to be safe clinical environments for the most challenging patient population in the mental health system.

Conclusion

The retraction of the high-security hospitals and reprovision of increased regional secure services are major changes which have widespread implications for the whole mental health and criminal justice system. Although, in principle, it is accepted to be the way forward, there are concerns regarding the current accelerated programme of retraction and reprovision.

There is lack of clarity regarding bed needs in high-security units. Projected bed numbers may be inadequate to meet the current level of need, particularly unmet need in prison. The timescales, revenue and manpower requirements for new regional services appear to take little account of the complexity of the task and the potential adverse effects on local mental health services. Clinical models in some new services may not take into account the complex needs of the population and particularly the implications of potentially very long lengths of stay for quality of life. Models of care which have been developed require evaluation in order to inform future service developments.

There is little evidence of either clinically informed national planning or cross-regional specialist commissioning for the smaller groups within the population requiring new services. There is already anecdotal evidence of potential adverse impact upon local mental health services. There is a need for the commissioning process to become more clinically informed and the complexity and inherent risks to be acknowledged and taken into account in the planning process. It is essential that the services and those agencies which relate to them are viewed as flexible, dynamic systems if they are to meet the needs of new cohorts of service users in the future.

Declaration of interest

None.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.