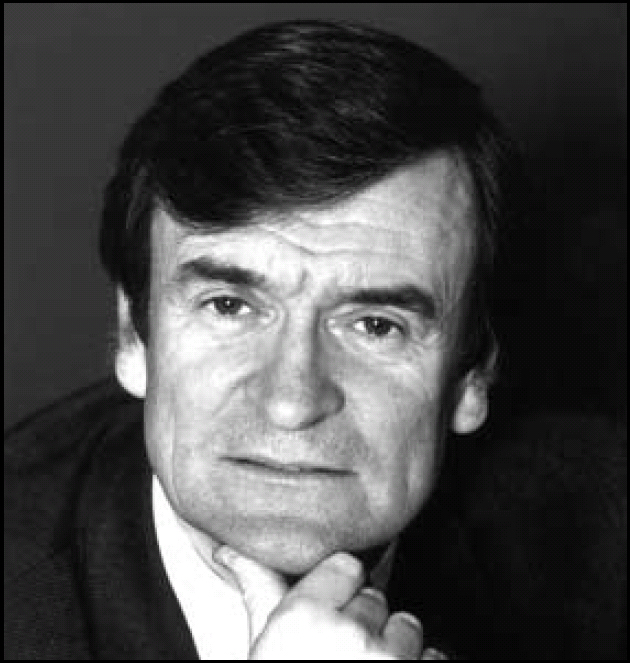

‘Psychiatry's Ambassador to the Public’ and formerly Professor of Psychiatry at St Bartholomew's Hospital, London, and later, at St Patrick's Hospital, Dublin

Anthony Clare, arguably the most brilliant and multi-talented psychiatrist of his generation, suddenly died, aged 64, of a heart attack in Paris on 28 October 2007. Thus ended the life of the man who did more than anyone else to improve the public understanding of psychiatry in Britain and Ireland. Tony was born in Dublin in 1942, educated by the Jesuits, and then went on to study medicine at University College, Dublin. I first saw him when, as a Glasgow medical student, I went along one Friday evening to the University Union debating chamber where the local aspiring politicians (including John Smith, Donald Dewar and Menzies Campbell) regularly mauled any debating team from any other University. However, this particular Friday was quite different: two visiting Irishmen totally demolished the arguments of the locals and reduced an initially hostile audience of students to roars of laughter and applause. Tony was a wonderful debater, and he and his colleaguewent on to win the Observer Mace Trophy, a highly sought after honour which was fought over between all UK and Irish Universities.

Tony qualified in Medicine in 1966, and did an internship in New York State, before returning to Dublin and then on to the Maudsley Hospital to train as a psychiatrist. I next saw him in 1972 during my induction to the Maudsley. While the various professors and consultants gave informed and well-meaning talks, by far the most impressive came from a Senior Registrar in a velvet suit, Tony Clare. While supposedly telling us about the on-call rotation, he managed to start off a lively discussion on some of the most controversial issues in psychiatry. This was typical for Tony, albeit from his relatively lowly position, he was in many ways the dominant figure in the Maudsley in the 1970s. He could as easily electrify a lecture theatre full of bored psychiatrists in the same way as he could initiate a heated philosophical argument at the lunch table on the role of diagnosis in psychiatry.

As a registrar, Tony Clare appeared fearless: he was equally undaunted by the President of the Royal College of Psychiatrists or the Minister of Health. He led a national revolt of trainees against excessive impositions from the nascent Royal College, and inspired the founding of a national organisation, the Association of Psychiatrists in Training, to fight for trainees. Indeed, his political skills resulted in junior psychiatrists having a surprisingly big say in decision-making about psychiatry for a decade; sadly, line-management and the follies of NHS bureaucracy later put paid to this.

© BBC

In 1976 Tony became a researcher in the General Practice Research Unit at the Institute of Psychiatry, and subsequently as the deputy to Professor Michael Shepherd. They made a very good partnership, Shepherd the aloof and rather frightening professor, and Tony, easily approachable and always in the thick of things, effectively running the Unit. Tony wrote his Thesis on premenstrual tension and edited several volumes on psychiatry in general practice. He became Vice-Dean of the Institute of Psychiatry in 1982, and then, the following year, Professor and Head of Psychological Medicine at Bart's. He was a hugely energetic head, building up an excellent department, and convincing an over-traditional hospital of the value of psychiatry. In 1989 he returned to Dublin and took up a Clinical Chair there together with the medical directorship of St Patrick's, one of the two main psychiatric hospitals. In 1992 he stood for one of the university seats in the Irish Senate but did not succeed, probably because he was still regarded as too anglicised by the local electorate; it was a major disappointment for him.

Tony loved communicating, becoming equally passionate in one-to-one conversation as when talking to millions. He first appeared as a guest on Radio 4's Stop the Week in the 1970s, and his Radio 4 series ‘In the Psychiatrist's Chair’ in which he talked with well-known people about their life, ran for two decades from 1982. He coaxed rather than pressurised his interviewees into revealing their motivations and, not infrequently, their fears. Unfailingly courteous and very perceptive, he gave a flavour of how the best psychiatrists try to understand people, without relying on what he regarded as outmoded Freudian theories. A cultural historian of the 1980s and 1990s could do worse than listen to the archives of ‘In the Psychiatrist's Chair’ because most of the major figures of the time were interviewed there. Tony also initiated ‘All in the Mind’ in 1988 and presented it for a decade. However, his scope in broadcasting was larger than just psychiatry. Because he could talk with such eloquence and wit on many subjects from literature, to theatre, to politics, he appeared as a guest on numerous TV and radio programmes in the UK and Ireland. He also penned regular articles for newspapers and magazines (occasionally, passing his house as late as 1 am, I would see him furiously typing away to meet a deadline).

Inevitably, any psychiatrist with so high a public profile will receive criticism. Initially, it was from senior psychiatrists irritated that a ‘jumped up’ registrar was the person asked to represent psychiatry in the media; later it was usually because of the jealousy of less articulate colleagues. Of course he made mistakes, but overall, Tony Clare was a better ambassador to the general public than psychiatry could have wished, or even hoped for. Articulate, charming, and so, so knowledgeable, he put a kindly yet intellectually rigorous face to our subject.

Tony wrote his first, and best, book, Psychiatry in Dissent, as a senior registrar. Until its publication in 1976, orthodox psychiatry had not known how to respond to the attacks of the anti-psychiatrists, R. D. Laing and Thomas Szasz, oscillating between trying to ignore them and alternately exploding with incoherent rage. Tony considered the arguments of the anti-psychiatric movement sympathetically and in depth, concluding that while it had little theoretical justification, it was a natural reaction to the dreadfully poor state of psychiatric practice in Britain and the USA. He wrote several further books, including three volumes based on his radio interviews, as well as Depression and How to Survive It (1994) which was co-written with the comedian Spike Milligan. However, none of these later books had such a profound influence as did Psychiatry in Dissent. This was, perhaps, because originally the material in it had been intended to be part of a psychiatric textbook. When his co-authors failed to produce their chapters, Tony turned what he had written into a book for the intelligent layman; thus it combined the detailed information and authority of a textbook with the ease of reading of a magazine article.

In 2001 he decided that he had done enough in the public sphere and, thereafter, worked quietly as a psychiatrist at St Edmundsbury Hospital in Dublin. He had been very well and was returning from a happy holiday with his wife Jane in Sardinia when he died suddenly of a heart attack during a stop-over in Paris on 28 October. He is survived by Jane and their seven children. There was a huge funeral on Thursday 1 November with 700 attendees, including half the political and media establishment of Dublin; particularly impressive was the number of his own patients who came to pay their personal respects and show their gratitude. His son Simon gave a touching farewell in which he pointed out that his highly energetic father packed an amazing amount into the average day, rushing from buying the family shopping and collecting the various children, to lecturing at medical school, seeing patients in hospital, and doing TV interviews; as a result, he was often running late. Sadly, said Simon, the one thing that Tony was early for in his life was his death!

Tony Clare's legacy includes many present-day psychiatrists who were persuaded to take up the specialty by the inspirational model that he provided. Tony himself did not always appreciate what a wonderful service he had done for our subject. For several years he declined the offer of an Honorary Fellowship from the Royal College of Psychiatrists, saying that he had not done enough to merit this. However, because the College kept coming back to him (and many thanks to the Officers!), he eventually gave in and accepted the Honorary Fellowship in 2007. This was very fitting because Tony was the psychiatrist who made the greatest impact on the public consciousness over the last 30 years, as demonstrated by the many tributes to him in the newspapers, TV and radio. After I left the funeral, I took a taxi to Dublin airport. The driver asked me where I had been. When I told him, he sighed and said ‘He was a grand man, that Tony Clare. I always listened to him whatever he was on. He made everything interesting’. He did indeed!

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.