I recently spent 6 months in Namibia as a Fellow of the John Simon Guggenheim Foundation. The purpose of my visit was twofold: the establishment of a database for trauma-related mental health disorders and the development of a validated, self-report screening instrument for mental illness. In the process, I was able to meet with Namibian colleagues and visit a number of health care centres in the country. This article will focus on my impressions of psychiatry in Namibia that were formed during my visit. A brief summary of Namibian history, in particular the country's relations with neighbouring South Africa, will help place my observations in a more meaningful context.

Background

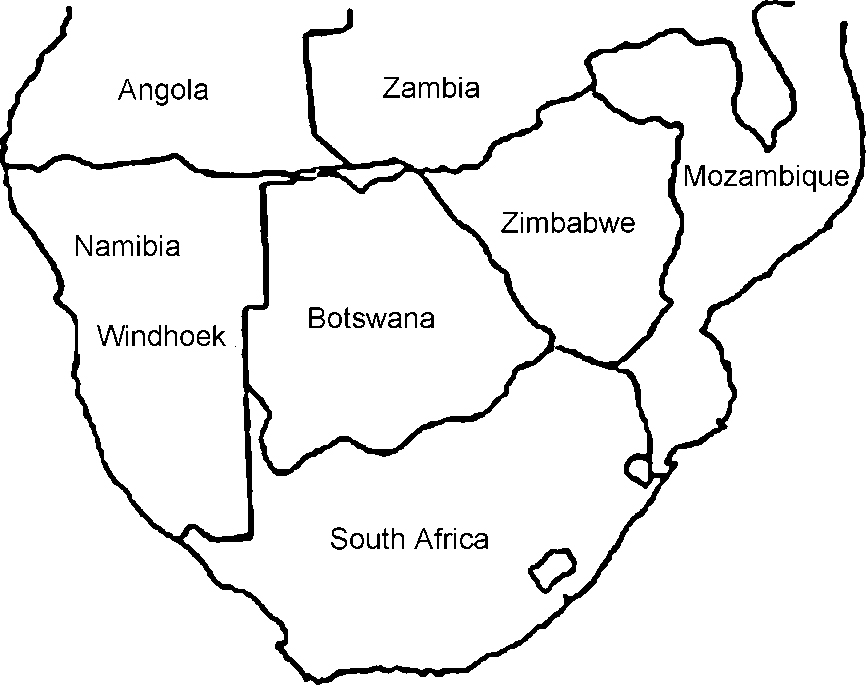

Namibia, a member of the Commonwealth, occupies a land mass one-and-a-half times the size of France. It is sparsely populated, the majority of the 1.8 million people being found in the northern region of Owamboland, below the Angolan border (Fig. 1). The original inhabitants were the San people followed by the Khoi-Khoi tribe, who were in turn displaced by the arrival of the Bantu approximately 2300 years ago. It was only in the late 19th century, with the European scramble for colonies in Africa, that Germany annexed the territory and called it German South West Africa. Conquered by South Africa during the First World War, the territory was thereafter governed as a protectorate by the South African administration under mandate from the League of Nations. The 1960s saw the end of colonial rule in many African countries. A protracted armed struggled ensued between South Africa and the forces of Namibian liberation, led by the South West African People's Organisation (SWAPO). Independence was achieved in 1990.

Fig. 1 Countries of southern Africa.

The rapid transition from protectorate to independence created difficulties for mental health services. Prior to 1990, health services, including mental health, were under the control of South Africa. This dependence was highlighted by the position of forensic services. Prior to independence, patients considered dangerous were sent to South Africa for assessment and treatment. This summarily stopped in 1990 and the prison system in Namibia became, by default, home to mentally-unwell offenders.

Areas of mental health concern

Epidemiological data are not available for specific mental illnesses. While the World Health Organization (WHO) is committed to obtaining such data worldwide, this undertaking has yet to reach Namibia (Reference KesslerKessler, 1999). The information I collected was, therefore, largely anecdotal and pertains mainly to mental health issues that have risen to prominence in the decade following independence.

Trauma-related mental illness

Given the protracted liberation struggle, many Namibians, both victims and perpetrators of violence, have been adversely affected. The deleterious effects of trauma-related psychopathology on Namibian society has been recognised with the development of a clinic for these disorders in the capital, Windhoek. This is funded by the Dutch.

HIV—AIDS related mental health problems

Large billboards, radio and television advertisements and newspaper editorials address the seriousness of the problem that has assumed the proportions of a national crisis as the epidemic cuts a swathe through Namibian society. With a health care system that has been over-whelmed by the number of ill patients, the psychological sequelae of diseases, such as major depression, anxiety disorders, psychosis and cognitive dysfunction, are seldom addressed.

Domestic violence

The past decade has seen a significant upsurge in domestic violence. During January to April 2000, 206 cases of child rape were reported to the police, a sixfold increase over the same period during the previous year. There are many explanations for this ‘epidemic’. During the liberation struggle, the country was united in a common purpose, the overthrow of the apartheid system. When that was achieved, there was an expectation on the part of many Namibians that independence would be associated with an immediate improvement in their living circumstances. However, while apartheid may have been defeated, its legacy was more enduring: social deprivation, unemployment, inadequate housing, traumatised families and missing relatives. The sudden euphoria of a new-found freedom was not sufficient to sustain indefinitely those in the population assailed by one or more of these problems and frustration has found an outlet in an upsurge in domestic violence. Furthermore, a political system that had dehumanised a people for decades appears to have generated a culture of violence that, in the absence of an external threat, is now being turned inwards.

Linked to these issues, substance misuse involving alcohol, cannabis and mandrax also appears on the increase. (Mandrax is a combination of the non-barbiturate sedative methaqualone mixed with diphenhydramine, most often smoked with cannabis (‘dagga’) in a preparation known as a ‘white pipe’.) Finally, anecdotal evidence points towards a significant increase in the rates of suicide, particularly in the north of the country, where the liberation war was most intense.

The liberation struggle is, however, unlikely to have impacted on the incidence of major mental illnesses such as schizophrenia and bipolar affective disorder. Management of these disorders before independence presented a considerable challenge to the limited mental health care services and continues to do so.

Resources and infrastructure

The Namibian terrain is dominated by the world's oldest desert, the Namib. The origins of the word are obscure but its meaning is ‘endless space’. And endless space is what the traveller confronts, for it is possible to travel vast distances without encountering anyone. The combination of great distance and relatively small population, when added to a paucity of mental health specialists, helps explain the considerable logistical difficulties in providing health care delivery to the population.

When it comes to treatment, all roads lead to Windhoek (the nation's capital) and Oshakati (the largest town in the populous north). Both have state-funded psychiatric in-patient facilities. After discharge, efforts are made to get the patients to see a psychiatrist every 3 to 6 months, but in practice, patients may receive no on-going care until their next relapse. Treatment of psychosis is, therefore, largely reliant on sporadic use of depot antipsychotic medication. Appeal against involuntary detention is rare.

Since independence, a Namibian forensic psychiatric service has been established. However, the country remains short of skilled mental health practitioners. Namibia has four psychiatrists, two of whom work in the state hospitals. Of 12 clinical psychologists, only one is in the state sector. There are no neuropsychologists. Those professionals in private practice will generally only see patients who have medical insurance, thus placing their expertise beyond the resources of most Namibians. The University of Namibia, the country's sole university, does not have a medical school.

Nurses, and to a lesser extent, social workers, provide the backbone of psychiatric care. Community psychiatric nurses, based at the state hospital in Windhoek, are responsible for running satellite psychiatric clinics in the greater Windhoek environs. However, the situation changes away from Windhoek and Oshakati, with community psychiatric nurses seldom being found.

The future

Training more mental health nurses and social workers and ensuring they focus exclusively on patients with psychological difficulties represents a cost-effective way for Namibia to address its mental health needs. Nurses do, however, need medical back-up and cannot prescribe medication. With so few psychiatrists, necessity dictates that medical officers fill the void. The psychiatric unit in Windhoek could not function without this arrangement and there are plans to extend this to the rest of the country by identifying physicians in district hospitals who have an interest in psychiatry. These doctors will then be offered an intensive 1-week, on-site course in basic psychiatry provided by a psychiatric nurse.

A single, long-term community facility, sponsored by the Lutheran Church, is currently operational. It is run by a lay person and houses 10 patients. In addition, the Ministry of Health proposes to build a series of community residences using a grant from the Finnish government. They will house six to eight patients, with one patient nominated as group leader.

These measures are, however, designed primarily for patients with more severe mental illness. Those Namibians who have been traumatised by war or domestic violence will need to look elsewhere. Apart from the Dutch-supported centre in Windhoek, I did not come across any programme or clinic that offers therapy designed to address these problems. Namibian communities traumatised by decades of war would, therefore, do well to look at other traumatised societies with limited resources and observe how they have gone about healing themselves. An excellent example in this regard is Mozambique, Africa's poorest nation, which has only recently emerged from one of the continent's most brutal civil wars. With half the country personally touched by violence, Mozambicans have responded by developing an uniquely creative home-grown model of healing and regeneration that embraces both victims and perpetrators alike (Reference NordstromNordstrom, 1997).

It would be remiss to conclude without mention of the role played by traditional healers. Their influence, particularly in rural communities, is often considerable. The Namibian Ministry of Health is cognisant of this fact and a new mental health initiative calls for providing some training in mental health to the Traditional Healers Association. In addition, avoiding conflict with traditional healers, for example, by not opposing their involvement with psychotic patients, provided the latter have received depot medication, is an innovative attempt to marry disparate cultures in a therapeutic alliance. It is too soon, however, to evaluate the success of this approach.

Declaration of interest

None.

Acknowledgements

Supported by a grant from the John Simon Guggeinheim Foundation. Map of southern Africa courtesy of Pippa Feinstein.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.