Programme budgeting is a technique designed to identify how much money has been invested in major health programmes (Reference Brambleby, Jackson and Muir GrayBrambleby et al, 2007). Information concerning levels of investment in mental health and other healthcare areas can be found on the Department of Health website (www.dh.gov.uk/en/Managingyourorganisation/Financeandplanning/Programmebudgeting/index.htm). Marginal analysis is an economic appraisal that evaluates incremental changes in costs and benefits when resources within a programme are increased, decreased or deployed in different ways (Reference Brambleby, Jackson and Muir GrayBrambleby et al, 2007).

The practical application of programme budgeting and marginal analysis (PBMA) has been described by Ruta et al (Reference Ruta, Mitton and Bate2005). The approach can be broken down into five essential steps. Steps 1 and 2 establish the total resources available and identify services on which these resources are currently spent. They allow for the relevant programme budget to be calculated. Step 3 involves identifying potential services as candidates for receiving additional or new resources (and the costs of potential benefits of putting such resources into growth areas) – the ‘wish list’. An assessment of existing services is then undertaken (step 4) to establish which can be provided equally effectively and with fewer resources, thus releasing resources to fund items on the wish list. Step 5 is arrived at when some items on the wish list still cannot be funded. It identifies services that should receive fewer resources, or even be stopped, because greater benefit would be reached by funding other items on the wish list. This collection of services becomes the ‘hit list’.

Fundamental to the above process is an economic evaluation of the marginal benefit gained per extra unit of resource for one service and the benefit lost from having one unit less in another. It is usual to form an advisory panel which will examine the costs and benefits of the proposed changes and make recommendations which can be acted upon by commissioners. The establishment of the advisory panel provides an opportunity to include a wide range of stakeholders, including service users and carers, as well as managers and clinicians.

National Health Service pilot PBMA

In 2007 the National Health Service (NHS) Institute for Innovation and Improvement funded a project to test the model of PBMA at the micro level (within programmes of care). Three sites were chosen as pilots: Norfolk, Yorkshire, and Humberside and Newcastle. The objectives of the project were to test the following.

-

1. Acceptability – do key stakeholders attend the advisory panels and engage in discussion?

-

2. Is it possible to populate the five key steps with data on inputs, outputs and outcomes?

-

3. Does this approach make a difference to patterns of service?

-

4. Do the participants value cross-fertilisation of ideas, perspectives from other geographical areas, input from different disciplines, patient viewpoint and a health economist as a facilitator?

-

5. Is it possible to make PBMA a regular feature of local commissioning discussions (sustainable, proportionate and affordable) in time for the 2008/09 financial cycle when the significant resource growth seen in recent years ceases?

We describe the pilot study conducted in Norfolk. The chosen programme of care was the mental health programme, category five (incidentally, the largest programme in terms of total funding) of the National Programme Budget project. The pilot project was organised by the Health Economics Group at the University of East Anglia with assistance from key members of Norfolk Primary Care Trust and Norfolk and Waveney Mental Health Partnership NHS Trust (NWMHP; it became Norfolk and Waveney Mental Health NHS Foundation Trust on 1 February 2008).

Method

The methods for conducting a PBMA analysis discussed in Ruta et al (Reference Ruta, Mitton and Bate2005) were adapted for the local pilot. A marginal analysis advisory group was formed to discuss possible changes to mental health services and to examine their costs and benefits. Five meetings were organised between April and October 2007. The membership was selected from locally established networks and included professional and managerial staff from the main NHS provider (NWMHP), commissioners, a public health consultant, representatives from the independent and charitable sectors, and representatives of service users and carers. General practitioner (GP) representation was also sought, although no GP ever attended any of the meetings.

The programme budget under consideration was Norfolk Primary Care Trust's NHS expenditure on mental health for the fiscal year 2006/7. It was assumed that no additional funds would be made available for the following year so that any judgements about investment would have to take into consideration the Trust's disinvestment in mental health. It was acknowledged that considerable disinvestment in mental health had already occurred and that the Trust planned a further disinvestment of £2 million, specifically from older peoples' services in the fiscal year 2008/9.

The advisory group was responsible for: developing and weighting a set of criteria that services could be judged against; identifying options for service change (the wish and hit lists); developing the possible options for change into well-defined outline business cases; and, finally, scoring these cases against the criteria.

All of the business cases originated with, and were subsequently developed by, members of the advisory group. A standard business case template was used and completed based on information from the professional literature, data held by local agencies and stakeholders, and from local professional opinion.

The average scores for each criterion were multiplied by the corresponding weights and summed together to produce an overall weighted benefit score. The business cases were then prioritised in terms of cost per person per benefit point (cost:value ratio; Reference Wilson, Rees and FordhamWilson et al, 2006).

Results

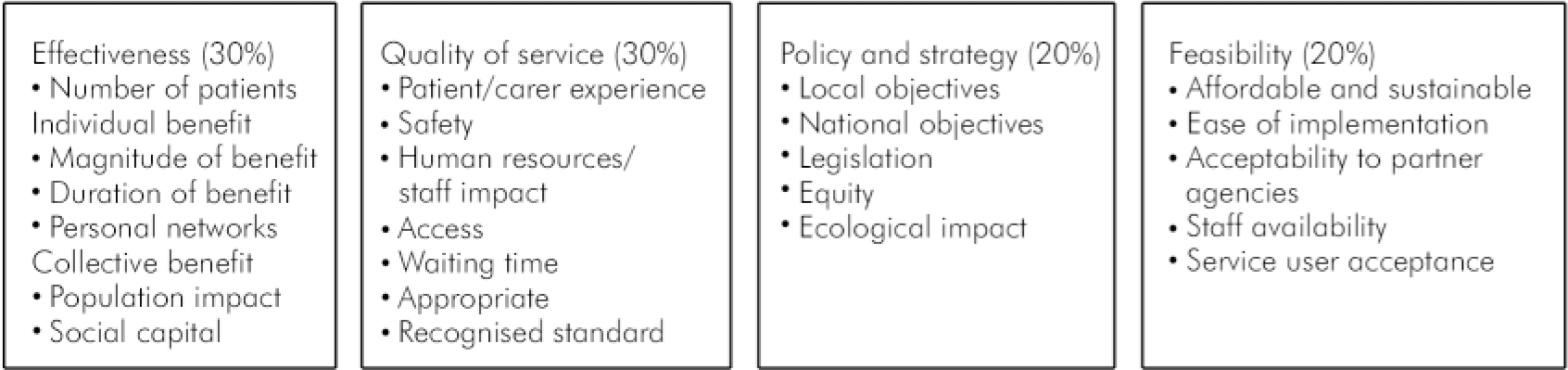

The advisory group identified 23 criteria against which to assess mental health services. These were clustered into four groups covering effectiveness, quality, policy and strategy, and feasibility. Effectiveness and quality were weighted 30% each, whereas policy and strategy and feasibility 20% each (Fig. 1).

A number of potential services for investment were identified. These included:

-

• mental health promotion in the community (e.g. reducing stigma);

-

• complementary interventions (arts, nutrition, exercise, acupuncture, social activities, relaxation techniques);

-

• clinical treatments (specifically, the provision of community-based psychological therapies, a nurse-led eating disorder service and an expansion of the existing assertive outreach services for severe and enduring mental illness);

-

• lifestyle support for service users and carers within the community;

-

• young peoples' services (such as a ‘one-stop shop’ for people with emotional problems aged 13–25 years).

Fig. 1. Criteria and weightings identified by the advisory group to assess mental health services.

The advisory group also identified potential items that could receive fewer resources. These included:

-

• reducing the volume of antidepressant prescribing in primary care;

-

• enforcement of a protocol for prescribing atypical antipsychotic medications devised between primary and secondary care;

-

• out-of-area specialist treatment placements;

-

• developing a newer model of delivery for crisis resolution and home treatment services;

-

• rationalising family support teams;

-

• restructuring day services, particularly within older peoples' provision;

-

• alcohol and drugs services.

There was the potential to release £3.77 million to fund the service expansion options. Business cases were then developed for six specific service areas.

-

1. ‘Gardening for health’ project.

-

2. Young persons' one-stop shop.

-

3. Assertive outreach services.

-

4. ‘Floating support’ (outreach tenancy support workers and benefit specialists).

-

5. Holistic mental well-being service (cognitive–behavioural therapy, support in the workplace, complementary therapies and guidance for self-management of well-being).

-

6. Nurse-led eating disorders service.

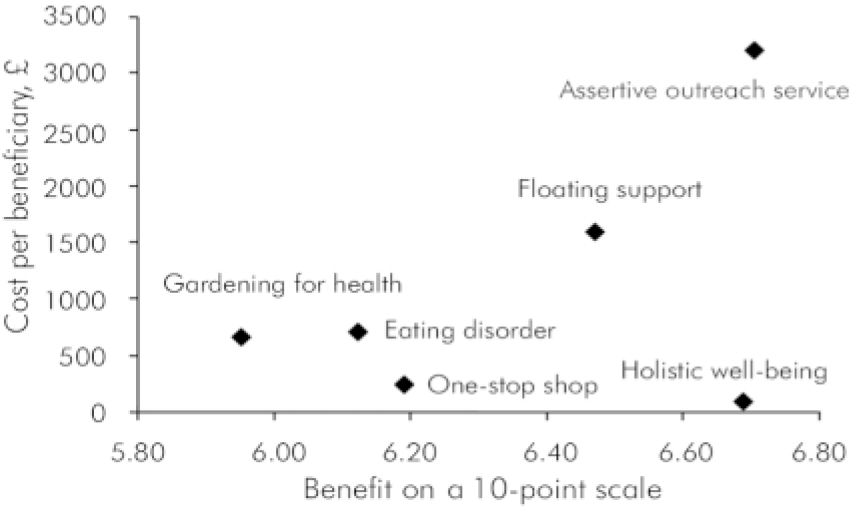

The costs per patient and benefit (out of a maximum score of ten) for each business case are shown in Fig. 2. Interestingly, expansion of the assertive outreach service was associated with the greatest additional benefit; however, this option was also the most costly per patient. In comparison, the marginal benefit of a holistic well-being service was judged to be almost as beneficial but significantly less costly.

The advisory group calculated that £194 000 would be released through changes to prescribing practices; this sum should be used to fund a holistic mental well-being service and to develop a young persons' one-stop shop. Additional sensitivity and threshold analyses added further weight to this conclusion.

Conclusions

The central importance of commissioning healthcare to achieve high-quality and personalised services that improve health and well-being within the population is a core plank of Department of Health policy (Department of Health, 2007). Decisions taken by commissioning bodies are likely to have a profound effect on the shape of mental health services at the provider level within England during the coming 5 years. However, the resources that are going to be available to commissioners are likely to be limited, as the rate of spending increase on the NHS observed for the period 2002-2007 is going to be considerably curtailed for the period up to 2011 (Reference Wanless, Appleby and HarrisonWanless et al, 2007). It is essential, therefore, that commissioning decisions are taken within an objective framework and in as inclusive a way as possible.

The future commissioning of mental health services is likely to arouse much controversy. Historically, the provision of mental health services has represented a broad church containing a wide spectrum of stakeholders and other interested parties. All stakeholders have a view about service provision and want this view heard. Although not without its limitations, PBMA provides one such framework that allows stakeholders to feel included within the decision-making process. It also provides an element of transparency concerning how decisions are taken. Ultimately, responsibility for commissioning decisions must lie with primary care trusts and their boards, but PBMA provides a framework that can inform a primary care trust board.

Fig. 2. Cost and benefit calculated for each business case identified by advisory group.

This pilot demonstrated that it was possible to engage (with the exception of GPs) a wide range of stakeholders who were prepared to work together and collectively provide recommendations to a primary care trust about investment and disinvestment decisions in mental health. Furthermore, the PBMA model was shown to provide a useful framework that enabled a structured approach to be applied to the decision-making process. The stakeholder members of the advisory group were generally satisfied with the outcome, and believed that their views had been incorporated into the process of decision-making.

Limitations

However, there are some weaknesses to highlight. First, important stakeholders were absent from the advisory group, most notably representatives from primary care/general practice. Given the development of practice-based commissioning and the central role that this is likely to play in commissioning mental health services, this is a significant weakness demonstrated by the pilot. If PBMA is to be adopted for future use, the early successful engagement of GPs must be seen as an essential step.

Second, given that it was the advisory group members who generated the ideas and themes for potential disinvestment and investment, certain arbitrariness was inevitable in terms of which specific business cases were initially favoured and then further developed. This point further emphasises the need to ensure that all relevant stakeholder groups are fully engaged and appropriately represented, if this method is to be adopted as a commissioning tool.

Third, there is an issue of training. No pre-pilot training in the use of PBMA was provided to any of the advisory group members. It can be reasonably argued that the provision of suitable training would result in better-informed judgements and decisions concerning priority setting and the feasibility of implementing decisions, particularly if the training was directed towards ensuring that all participants share a similar awareness of the potential impact of any decisions taken for the mental health system as a whole.

The pilot was an experiment and the outcomes have not, therefore, had any direct impact on the commissioning priorities of Norfolk Primary Care Trust for the 2008/9 commissioning round. However, it has been indicated from within the Trust that there is interest in using PBMA as a framework for future commissioning of mental health services.

Any health economy intending to adopt PBMA to aid the process of commissioning mental health services in the future is advised that well-informed decisions that can be realistically implemented are more likely as an outcome if the weaknesses highlighted above are addressed at the outset.

Whatever tools or the form of commissioning used by primary care trusts and other commissioning bodies, the fullest involvement and engagement of psychiatrists and other NHS mental health professionals in the commissioning process is essential, if the future direction of mental health services is going to be significantly shaped by orthodox thinking and concepts.

Declaration of interest

None.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Mark Jennings from the NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement who granted funding for this project. Thanks also to Dr Peter Brambleby, currently Director of Public Health, North Yorkshire and York Primary Care Trust and North Yorkshire County Council, who in his former role of Consultant in Public Health, Norfolk Primary Care Trust initiated and led the early stages of the Norfolk pilot and who also provided expertise in the PBMA process. Thanks also to the members of the advisory group for their participation and to an anonymous reviewer for making very constructive comments and observations about the manuscript.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.