Drug treatment for dementia has been increasingly available in the UK since 1997. Trials have repeatedly reported the effectiveness of cholinesterase inhibitors for Alzheimer's disease (Reference Rogers, Doody and MohsRogers et al, 1998; Reference Farlow, Anand and MessinaFarlow et al, 2000; Reference Wilcock, Lilienfeld and GaensWilcock et al, 2000) and further work has reported effects of these agents in other dementias (Reference McKeith, Del Ser and SpanoMcKeith et al, 2000; Reference Erkinjutti, Kurz and GauthierErkinjutti et al, 2002) and of memantine, a glutamate antagonist (Reference Reisberg, Doody and StofflerReisberg et al, 2003). National service developments, including the National Service Framework for Older People (Department of Health, 2001) and National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE, 2001) guidance on the prescription of cholinesterase inhibitors have driven forward the widespread use of antidementia drugs in the National Health Service. Many service configurations may be used to deliver these medications, including traditional out-patient clinics, specialised comprehensive memory clinics and general practitioner prescription. Factors common to services prescribing these medications are likely to include specialist control of assessment, initiation of treatment and review of response, and local arrangements between primary and secondary care over ongoing prescribing. A specialised community-based service in Coventry is dedicated to the management of patients on antidementia drugs. Key features of the service are staff providing a domiciliary service dedicated exclusively to the delivery of drug treatments for dementia.

The aims of this paper are: (a) to describe this service; (b) to establish activity/case mix; (c) to assess clinical outcomes for patients of this service.

Method

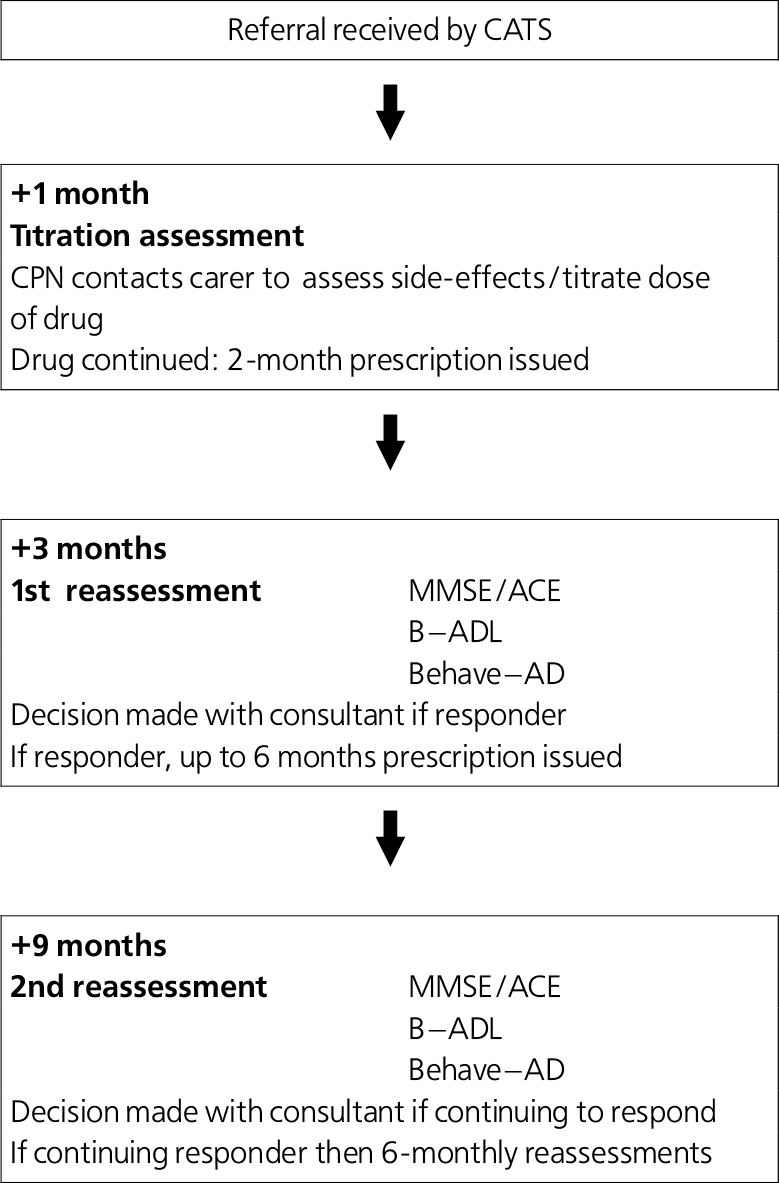

The Cognitive Assessment and Treatment Service (CATS) was established in Coventry in March 2002. Funding was negotiated to support three dedicated senior (G grade) community psychiatric nurses and a half-time secretary. All patients identified as having dementia suitable for treatment with antidementia drugs are referred by consultants to this team. An assessment and treatment protocol is followed as shown in Fig. 1. Almost all assessments are carried out in patients’ homes. The team nurses deliver all drugs to the patients/their carers and monitor adherence and side-effects. After reassessments, consultants decide on further prescribing during supervision sessions with nursing staff.

We identified all new referrals to the team between 1 October 2002 and 31 March 2003. For each referral, the following details were recorded via a pro forma by team nurses.

Demographic/clinical data

We recorded age, gender, living and care arrangements and the diagnosis given in the consultant referral letter.

Service data

We recorded time from referral to assessment and from initiation of treatment to first reassessment. We also recorded the drug used and the outcome of the assessment (continuation/or stopping drug).

Fig. 1. The Cognitive Assessment Treatment Service (CATS) team assessment protocol. (CPN, community psychiatric nurse; MMSE, Mini-Mental State Examination; ACE, Addenbrooke's Cognitive Examination; B-ADL, Bristol-Activity of Daily Living scale

Outcome data

Cognition was measured using the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE; Reference Folstein, Folstein and McHughFolstein et al, 1975) or Addenbrooke's Cognitive Examination (ACE; Reference Mathuranath, Nestor and BerriosMathuranath et al, 2000). Function was measured with the Bristol-Activity of Daily Living scale (B-ADL; Reference Bucks, Ashworth and WilcockBucks et al, 1996). Behaviour was recorded using Behave-AD (Reference Reisberg, Borenstein and SalobReisberg et al, 1987).

Summative and descriptive statistics were used to describe the patient group. To analyse change in assessment scores over time, paired t-tests (for normally distributed scores) or Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed-ranks tests (for non-normally distributed scores) were used.

Results

A total of 181 new referrals were received by the team in the period audited. Full information was available for 166 (91.7%) of these referrals. Of these, 40 were excluded, 15 because they were for prescription only (assessments being done at the memory clinic) and 25 as they could not be assessed after referral (e.g. died, became too ill or refused assessment). This left a sample of 126 patients who were referred and followed the CATS assessment protocol. Of these, 24 were continuing treatment after clinic initiation and 6 were assessed but not initiated on treatment. A total of 96 patients were thus initiated on treatment by the CATS team.

Of the 96, 55 (57.3%) were given a diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease, 18 (18.8%) vascular dementia, 3 (3.3%) mixed vascular/Alzheimer dementia, 13 (13.5%) were recorded as dementia unspecified, and 7 had other diagnoses recorded, including dementia with Lewy bodies, dementia in multiple sclerosis and mild cognitive impairment. Mean age was 80.1 years (range 59-98) and 64 (66.7%) were female. Thirty-five (36.5%) lived alone. Mean baseline MMSE score was 20.0 (range 0-28). Seventy-five (78.1%) were initiated on donepezil, 9 (9.4%) on galantamine, 5 (5.2%) on rivastigmine and 7 (7.3%) on memantine. Mean time from referral to baseline assessment was 7.3 weeks (range 0-29). Of those initiated, 19 (19.8%) withdrew before the 3-month assessment could be completed. Eleven withdrew owing to side-effects, 4 owing to physical illness developing, 3 were nonadherent with medication and 1 died before reassessment. First reassessments were completed (n=77) a mean of 3.7 months after initiation of the drug. Of the 77 patients completing the course of treatment, 69 (89.6%) were judged responders and continued on treatment. Table 1 shows the outcomes according to assessment scores for those completing.

Table 1. Clinical outcomes for those completing first reassessments (n=77)

| Baseline Mean score (s.d.) | First reassessment Mean score (s.d.) | Z | t | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MMSE (n=44)1 | 20.0 (5.0) | 21.9 (4.1) | 3.197 | 0.001** | |

| ACE (n=25) | 41.0 (7.2) | 43.6 (9.4) | 1.832 | 0.079 | |

| B—ADL (n=67) | 6.4 (5.6) | 4.2 (6.1) | 2.862 | 0.006** | |

| Behave—AD (n=66) | 16.3 (10.6) | 14.0 (8.8) | 3.427 | 0.001** |

There was a statistically highly significant improvement in scores measuring cognition, behaviour and function.

Discussion

Of the many service models that might deliver antidementia drug treatments, most are likely to be clinic-based. To our knowledge, this is the first description of a service that employs experienced nursing staff solely to ensure the effective drug treatment of dementia and which delivers the intervention in patients’ homes. The benefits of a home-based service are considerable; the most obvious is the combination of enhanced convenience for patients and reduced non-attendance rates (Reference Anderson and AquilinaAnderson & Aquilina, 2002). The tasks delegated to the specialist nurses enabled the sharing of a large workload, which may have otherwise significantly prolonged patient waiting lists. We believe that employing experienced community nurses benefits both patients and other members of the services. The CATS nurses provide continuity in assessment and have an important pastoral and practical role in directing patients and carers towards appropriate services. Using these common and comprehensive response measures makes decisions about continuing treatment easier.

The service conforms to current NICE guidance, which recommends specialist diagnosis and initiation of treatment, assessments of cognition, activities of daily living, and behaviour, and assessment of response 2-4 months after initiation of treatment. The service treats large numbers of patients and our outcomes are comparable to, or better than, those found in both published randomised controlled trials of antidementia drugs (Reference Rogers, Doody and MohsRogers et al, 1998; Reference Reisberg, Doody and StofflerReisberg et al, 2003) and in reports of open studies of the use of donepezil in a UK memory clinic (Mathews et al, 2000). In particular, we believe the demonstration of benefits for cognition, function and behaviour is important. Our drop-out rate is comparable to those in controlled trials (Reference Rogers, Doody and MohsRogers et al, 1998; Reference Wilcock, Lilienfeld and GaensWilcock et al, 2000).

This study has a number of limitations. Significant benefits may follow from non-specific aspects of the service, such as instillation of hope and initiation of nondrug services suggested by the team's nurses. It was beyond the scope of this study to consider the economic implications of introducing this service configuration and there was no comparison arm of another such service. Importantly, patients referred to the service were heterogenous in terms of both diagnosis and severity of illness and a variety of drug treatments were initiated. We believe that the offer of treatment to some patients with diagnoses other than Alzheimer's disease, and the use of a range of available drugs, is probably typical of practice in the UK, which may make our outcomes more generalisable.

The clinical implications of this study are that a dedicated home-based service for the drug treatment of dementia can achieve high levels of clinical activity, is adherent to NICE recommendations on assessment protocols and achieves comprehensive outcomes at least as good as those reported in controlled trials. The recent report on the AD2000 trial (AD2000 Collaborative Group, 2004) and recent uncertainty in the UK over future availability of antidementia drugs have drawn attention to the possibility that clinical benefits from the use of cholinesterase inhibitors may be too small to justify their cost. Although this is an open report of service outcomes, with resultant biases, we believe that the outcomes reported show a real clinical benefit for patients/carers. We believe that models of service delivery may have substantial impacts on patient outcomes and that this model may be attractive to services deciding how best to organise treatment for this vulnerable group.

Declaration of interest

B.S. has received support to attend a conference from Janssen-Cilag and Eisai. K.S. has received sponsorship from Shire, Janssen-Cilag, Eisai, Pfizer, Lundbeck and Novartis.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the efforts of the CATS team in this work: Joe Marley, Amanda Hill, Nicola McEwan and Melanie Ward.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.