General hospitals need good access to psychiatric services for two reasons. First, there is much psychopathology associated with physical illness. Second, many acute psychiatric presentations (including those following self-harm) are handled by the general hospital, especially their accident and emergency departments. For this reason, the 2003 joint report of the Royal College of Physicians and the Royal College of Psychiatrists recommended that multidisciplinary liaison psychiatry services (including nurses, clinical psychologists, social workers and trainee psychiatrists led by a consultant psychiatrist with special training in liaison psychiatry) should be established in all general hospitals. They also recommended that they should be based on the main hospital site, have adequate administrative arrangements and be jointly funded (Royal College of Physicians & Royal College of Psychiatrists, 2003). Similarly, one of the recommendations of the Joint Working Party of the Royal College of Psychiatrists and the British Association of Accident and Emergency Medicine report (1996) was that the provision of a high-quality psychiatric service to the accident and emergency department depends on adequate and appropriate staffing of a multidisciplinary liaison psychiatry service (Royal College of Psychiatrists & British Association of Accident and Emergency Medicine, 1996). One definition of ‘appropriate staffing’ for such a service included a minimum of five consultant sessions per week (for the average district general hospital), a nominated consultant with responsibility for self-harm and accident and emergency, and one clinical nurse specialist per average-sized liaison psychiatry department (Reference House, Hodgson, Benjamin, House and JenkinsHouse & Hodgson, 1994).

In the light of these recommendations, we decided to study liaison psychiatry provision within six strategic health authorities. We questioned whether there is evidence of rational planning in liaison psychiatry service provision.

Methods

We contacted all acute National Health Service (NHS) trusts in the northeast of England by telephone to obtain contact details for their liaison psychiatry service(s). We then sent a postal questionnaire to liaison psychiatry practitioners working within all teams in the northeast of England. Copies of the questionnaire were sent to two members of each team (unless it was a one-person team) (n=70). We sent a second copy of the questionnaire to non-respondents after 6 weeks and followed up with a telephone reminder if it was not returned subsequently.

Area

The region covered was defined by the strategic health authority boundaries (Trent, South Yorkshire, West Yorkshire, North and East Yorkshire and Northern Lincolnshire, County Durham, and Tees Valley and Northumberland Tyne and Wear) (Fig. 1).

Figure 1 Map of the liaison psychiatry services surveyed in the six strategic health authorities

Questionnaire

The questionnaire sought information in the following areas:

-

• Team members and recent changes

-

• Supervision arrangements

-

• Nature of services (clinics, day patient facilities, helplines, etc.)

-

• Estimates of workload

-

• Main problems referred, including ages covered

‘Number of hospital beds’ in the general hospital NHS trust within which the liaison psychiatry service operated was used as an indicator of need (Department of Health, 2002).

Analysis

The quantitative response items are presented using descriptive statistics. Qualitative items were analysed using thematic analysis to be able to group responses. The qualitative items were analysed by two independent people and the results pooled.

Results

100% of general hospital trusts provided usable data; 8% (3/36) had no liaison psychiatry service. The rest of the results refer to the respondent trusts that have a liaison psychiatry service (33 services).

Service provision

Table 1 shows the distribution of liaison psychiatry services provided to the participating trusts. Despite the fact that only 24% of services provided disorder-specific out-patient clinics, these covered over 10 medical subspecialities. All services that responded provide a service for working age adults and 69% provide some services to over-65s. Sixty-one per cent of services said their referral rate had increased and 55% had increased their capacity over the past 3 years. Sixty-one per cent of services did not have their office on general hospital property and 38% of services had no current arrangements for supervision from a consultant psychiatrist.

Table 1. Profile of 33 liaison psychiatry services

| Service | Number of liaison psychiatry services providing each service (%) |

|---|---|

| Self-harm assessments | 31 (94) |

| Follow up for self-harm | 21 (64) |

| Accident and emergency assessments | 26 (79) |

| Follow up for accident and emergency assessments | 16 (48) |

| In-patient ward assessments (excluding self-harm) | 17 (52) |

| In-patient liaison psychiatry unit | 2 (6) |

| Liaison psychiatry out-patient clinics | 14 (42) |

| Disorder-specific out-patient clinics e.g. renal, cardiovascular, oncology, etc. | 8 (24) |

| Day patient services | 1 (3) |

| Helplines | 12 (36) |

Personnel

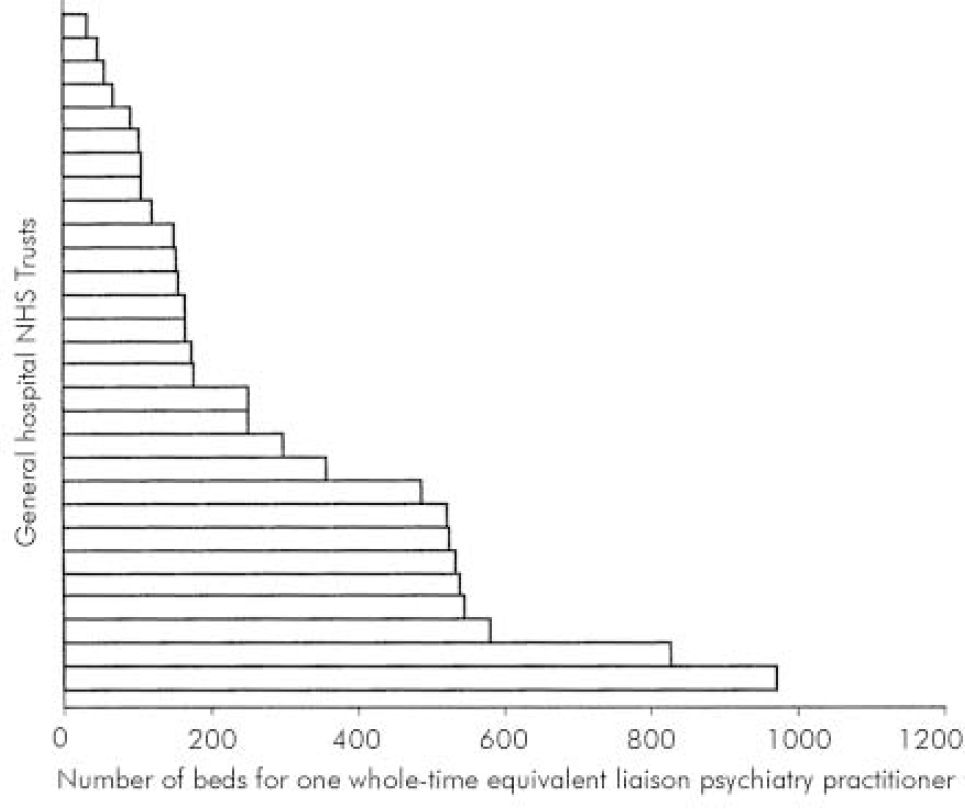

Forty-one per cent of services were not multidisciplinary, with their only staff being nurses. No service contained a clinical psychologist. Only 38% of services had designated consultant psychiatry time (25% met the recommended minimum of 0.5 whole-time equivalents). Fifty-five per cent had no administrative support. We calculated work rate by identifying the number of whole-time equivalent clinical staff (any discipline) in each service and the number of beds in the trust served by those staff. Figure 2 shows the number of general hospital beds for one whole-time equivalent member of the liaison psychiatry team in the trusts surveyed.

Figure 2 The number of beds in the general hospital NHS trust per one whole-time equivalent liaison psychiatry practitioner

Discussion

Our study gives a complete picture of liaison psychiatry service provision in the six northeast strategic health authorities surveyed. We do not know whether it is typical of England as a whole, but suspect that it is.

How does liaison psychiatry service provision relate to College recommendations?

In the past decade, there have been two College reports recommending changes to liaison psychiatry service provision (Royal College of Psychiatrists & British Association of Accident and Emergency Medicine, 1996; Royal College of Physicians & Royal College of Psychiatrists, 2003). Despite these reports, the findings of this survey highlight similar problems to those found by a survey of liaison psychiatry services in 1990 (Reference Mayou, Anderson and FeinmannMayou et al, 1990). There are still general hospital NHS trusts that do not have a liaison psychiatry service, although lack of provision is less of a problem in the northeast compared with the southwest (Reference Howe, Hendry and PotokarHowe et al, 2003). Current liaison psychiatry services are not multidisciplinary. Most have nursing staff, none contain integrated clinical psychologists, many lack administrative support and only a quarter have the recommended minimum consultant psychiatrist input. This could indicate that the functions a multidisciplinary team has in assessment, diagnosis, supervision and interventions in this client group are undervalued. It also highlights that the specialist skills a consultant liaison psychiatrist offers in terms of leadership, diagnosis, medical interventions and liaison with consultants from other specialities are poorly understood (Royal College of Physicians & Royal College of Psychiatrists, 2003).

Finally, only a third of services surveyed have their base within general hospital grounds. This could reflect the status of liaison psychiatry within the general hospital and distance will also affect patients’ waiting times for an assessment.

How does liaison psychiatry service provision relate to need?

It is clear that there is a wide variation in the number of general hospital beds per liaison psychiatry practitioner. This survey shows that 14% of general hospital NHS trusts do not even receive a specialist self-harm service. Sixty-nine per cent of working age liaison psychiatry services provide a service to over-65s. This supports the results of a recent survey of consultant old age psychiatrists that found 71% of respondents felt the current liaison psychiatry service they provided was poor and required improvement (Holmes, 2002). This gap in provision is being covered by already understaffed services.

It is unclear from this survey whether the idiosyncratic provision of liaison psychiatry-specific out-patient clinics relate to differing general hospital NHS trust needs or represent an unacceptable variation in service provision (Secretary of State for Health, 1998). This would be an interesting area for further investigation.

Clinical implications

Many government initiatives are driven by the fact that variations in services across the country are unacceptable, and result in poor quality of care and inequality of service provision (Secretary of State for Health, 1998). Unfortunately this is the case for liaison psychiatry, and patients of different general hospital NHS trusts will receive vastly different services for their psychiatric needs according to the structure of the liaison psychiatry service provided. This lack of rational planning of liaison psychiatry services means that many services are not needs-based and do not comply with College recommendations. Key areas that need to be addressed are the lack of multidisciplinary liaison services and inadequate consultant liaison psychiatry input.

Declaration of interest

None.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all staff from the liaison psychiatry services surveyed that responded to the questionnaire.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.