The significance and extent of communication difficulties between National Health Service (NHS) primary and secondary care services, particularly in London, are well established (Reference Kerwick, Tylee, Goldberg, Johnson, Ramsay and ThornicroftKerwick et al, 1997). When the project reported here began, these difficulties were clearly reflected in local tensions between service providers. Overstretched community mental health teams (CMHTs) were dissatisfied with high rates of clinic non-attendance among new referrals to the team, and had a negative perception that general practitioners (GPs) involved CMHTs too readily in the care of those with less severe mental health problems. General practitioners, in turn, wanted CMHT members to be more accessible by becoming practice-based. Letters were the most commonly used form of communication between the two, and were frequently regarded as inadequate.

Developing more effective shared care between primary and secondary services is a key feature of the National Service Framework for Mental Health (Department of Health, 1999). Although the acceptability of a protocol-based approach in primary care remains controversial (Reference KendrickKendrick, 2000), guidelines can be effective in influencing professional practice, but only when accompanied by dissemination and implementation strategies (Reference Grimshaw and RusselGrimshaw & Russel, 1993). There has been recent interest in collaborative initiatives to improve the communication between primary and secondary care services (Reference JankowskiJankowski, 2001). Strategies for dissemination aim to raise participants’ awareness, and evidence-based approaches include the use of ‘printed educational materials’ (Reference Freemantle, Harvey and WolfFreemantle et al, 2000): in our study these materials concisely described the project's rationale, aims and organisational endorsements. Implementation strategies aim to influence participants’ decisions and actions: we adopted a ‘decision support system’ (Reference HuntHunt, 1998) in the form of laminated A4 desktop ‘reminders’ for GPs and CMHT members and ‘ performance feedback’ (Reference Jamtvedt, Young and KristoffersonJamtvedt et al, 2003) in the form of 6-monthly audit reports sent to participating practices and CMHTs.

The aim of this project was to explore the effectiveness of using this combination of evidence-based dissemination and implementation strategies to support a locally-developed written communication protocol for GPs and CMHTs, using the relevance and reliability of their routine written communication about newly referred patients over a 2-year period as an outcome measure.

Method

Setting

Paddington is a typical inner-city area of London with a total population of 80 000 persons, comprising a substantial mix of ethnic groups, and of affluence and deprivation. North and South Paddington CMHTs operate an open referral system from at least 46 referring general practices in the area.

Sample

Through the provision of link workers, the CMHTs had established connections with the 26 practices (link practices) referring the most new patient cases each year. A random sample of new patient names was selected from all new link practice referrals from the Central and North West London Mental Health Trust's clinical information system, for each period of the study. For each case, the GP's referral letter was traced from the patient's file in the CMHT records library. The same method was used to select an independent, random sample of CMHT letters for patients participating in a first assessment at any time over the preceding 12 months.

Developing the protocols

The project team comprised a project worker (T.W.) and psychiatrist (S.M.) working with an advisory group made up of a local GP, a community psychiatric nurse and a CMHT administrator. The important components of written communication between primary and secondary care services were agreed by consensus and provided a provisional framework of information items for both GPs’ referral letters (Box 1) and CMHTs’ new assessment letters (Box 2). Following discussion between the project team and a wider group of local GPs at their postgraduate educational meeting and with members of the participating CMHTs at their weekly team meetings, the final protocols were agreed.

Strategies for dissemination and implementation

At the start of the project, copies of the protocols and accompanying information were sent by post to all participating link practice GPs and CMHT members, together with a desktop decision support tool that would act as a reminder of the relevant items to be included in clinical letters. Updates were sent out at 6-monthly intervals throughout the project. Performance feedback (Reference Jamtvedt, Young and KristoffersonJamtvedt et al, 2003) was provided by posting baseline and successive audit results to participating practices, at the start of the project and at 6-monthly intervals thereafter. In addition, CMHT link workers were asked to discuss the protocols in detail at the practice meetings they attended, and if possible with individual members of the primary health care team.

Box 1. Quality criteria for general practitioners’ referral letters to the community mental health team

-

• Presenting problem

-

• Past psychiatric history

-

• Current social circumstances

-

• Current psychotropic medication

-

• Patient's view of the referral

-

• Statement about risk and urgency

Box 2. Quality criteria for community mental health teams’ new patient assessment letters to the referring general practitioner

-

• Provisional diagnosis

-

• Prognosis

-

• Treatment plan - psychological interventions

-

• Treatment plan - pharmacological interventions

-

• Treatment plan - psychosocial interventions

-

• Named principal mental health worker (care coordinator)

-

• Details of next appointment

Developing the audit tool

Protocol criteria provided the basis of an audit tool designed to detect whether audited letters contained the recommended information items. To improve the tool's reliability, it was piloted on a small sample (n=10) by the two members of the project team independently before it was finalised.

Data collection

Data were gathered from the letters held in patient files in the patient services library at the CMHTs for three separate periods: ‘time 1’ was the 12-month period prior to the project starting (these data served as a baseline measure); ‘time 2’, and ‘time 3’ were consecutive 12-month periods during which the project ran.

Data analysis

Data were entered onto an Access database spreadsheet, summated and expressed as means, and analysed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences, version 10. Non-parametric data were analysed using the Kruskal–Wallis and χ-squared tests.

Results

General practitioners were the source of the largest number of referrals, with the next largest number coming from the local accident and emergency department. Participating (link) practices accounted for around half of the GP referrals during each study period. The proportion of these patients who completed an assessment with the CMHT increased significantly over the course of the study (Table 1).

Table 1. Comparison of all referral categories, general practitioner referrals and link practice referrals, completed CMHT new assessments and shared case-load size over the three study periods

| 1997-1998 | 1998-1999 | 1999-2000 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total annual referrals to Paddington CMHTs: n | 1056 | 945 | 996 |

| Annual GP referrals: n (% of total) | 661 (63) | 550 (58) | 614 (62)1 |

| Annual link practice referrals: n (% of all GP referrals) | 556 (53) | 417 (44) | 476 (48)1 |

| Link practice new referrals completing CMHT assessment: n (% of link practice referrals) | 369 (66) | 276 (66) | 423 (89)2 |

Quality of referral letters

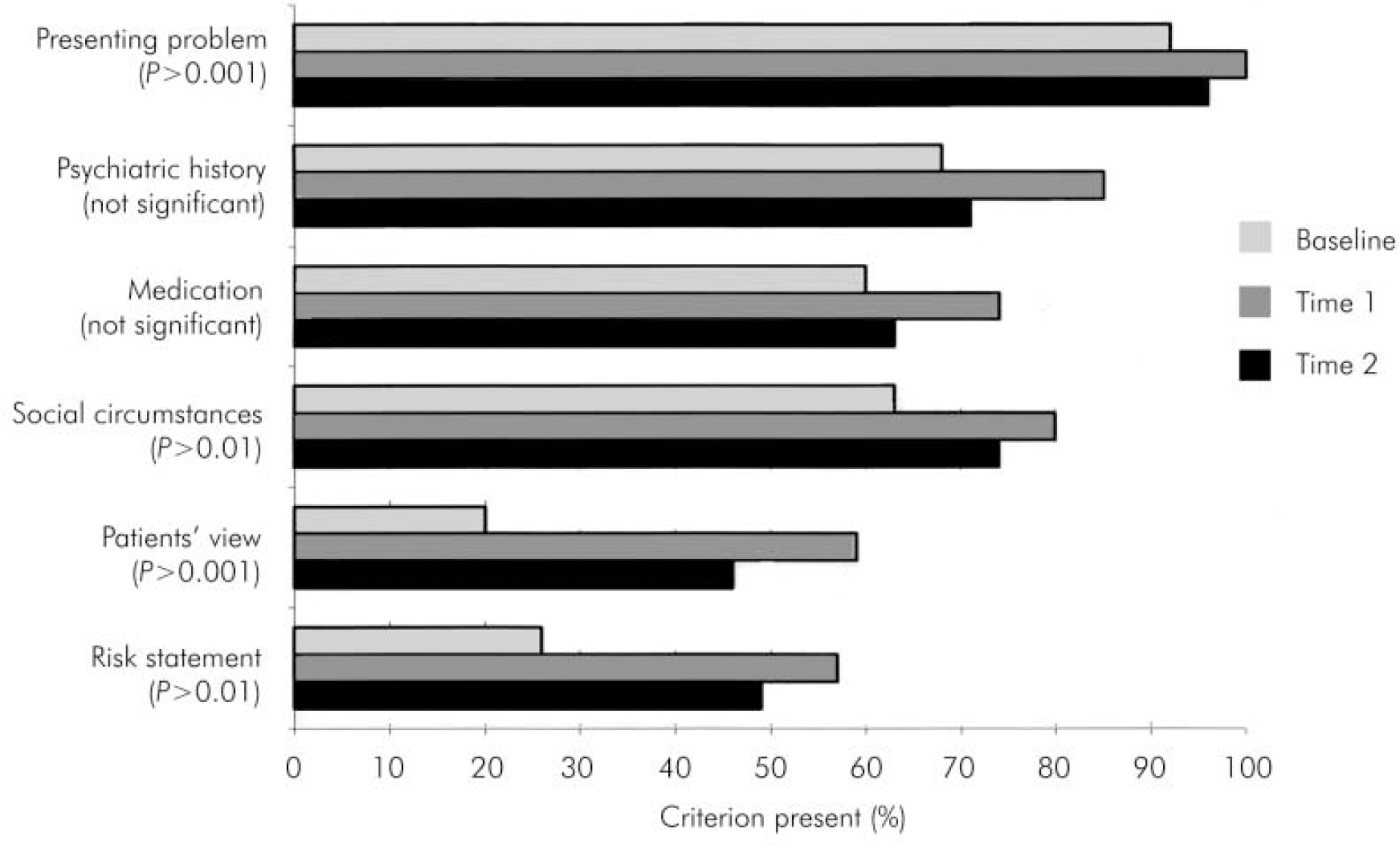

At the end of time 2, there was a trend towards improved performance for all six GP referral letter criteria compared with the baseline standard. At time 3, performance had deteriorated in comparison with time 2. During the course of the project, improved performance was statistically significant for four of the six criteria (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Compliance of general practitioner referral letters with six quality criteria at 3-yearly intervals.

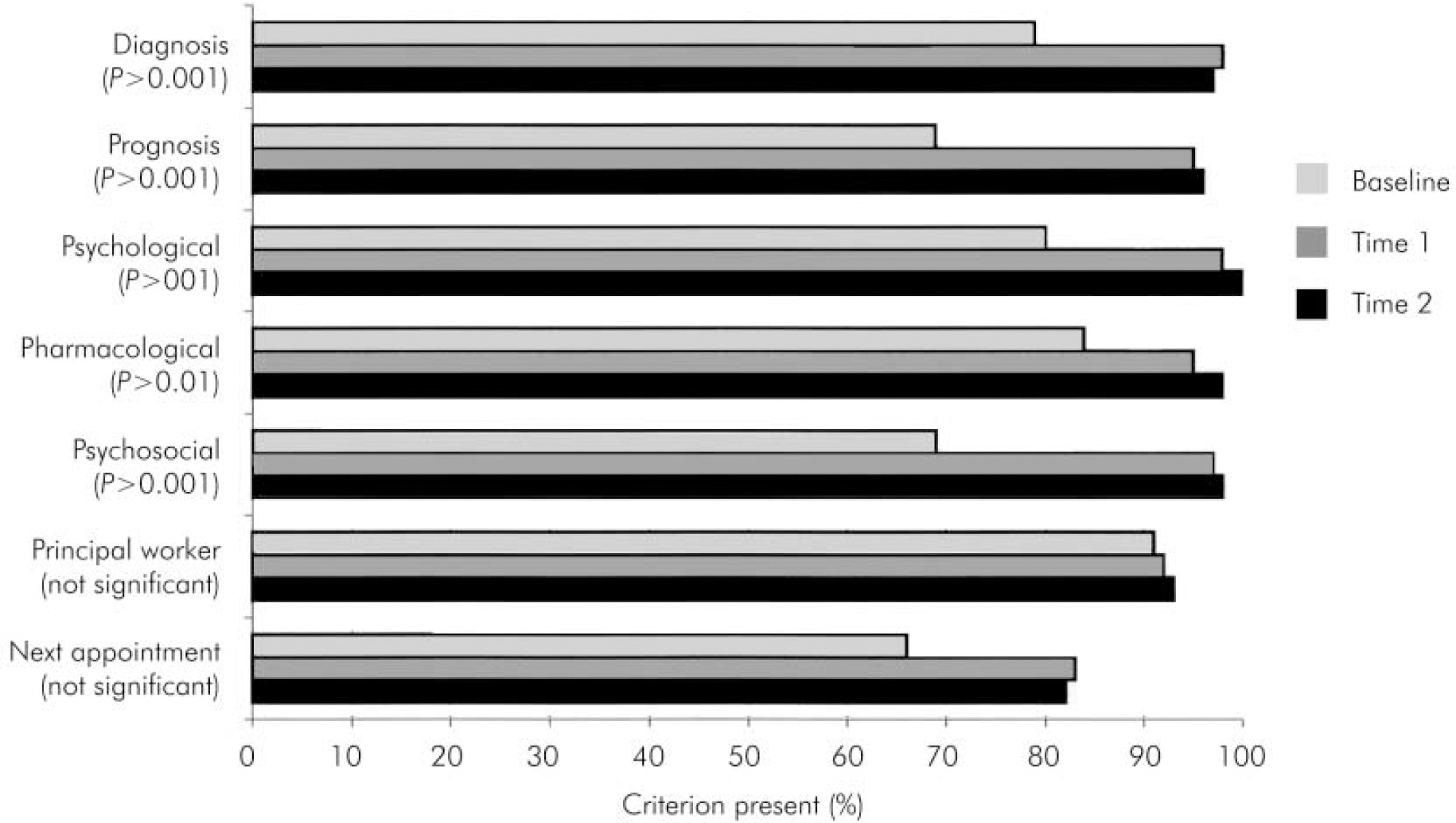

Quality of CMHT letters

At time 2, CMHT letters showed improvement on all seven criteria compared with the baseline measures. At time 3, further improvement was evident on five of seven criteria and there was marginal deterioration on two criteria. Overall, performance had improved significantly on five of seven criteria since the quality initiative began (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Compliance of community mental health team letters with seven quality criteria at 3-yearly intervals.

Reliability of correspondence

The completeness of CMHT clinical records was used as a proxy measure for the reliability of correspondence exchanged between practitioners. The percentage of assessments accompanied by routine correspondence from the CMHT to the GP increased progressively during the project, but by time 3 no CMHT correspondence to the GP could be traced in 15% of cases. Although all GP referrals were made in writing, by the final year no GP letter could be traced in 13% of cases. Taken together, these findings suggest that either the administrative procedures supporting the clinical communication task, or the reliability with which the clinical task was performed, or a combination of the two, remained unreliable (Table 2).

Table 2. Comparison of sample size and number of letters traced for general practitioner and community mental health team correspondence

| Time 1 | Time 2 | Time 31 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| GP letters | |||

| Sample size: n | 80 | 78 | 2601 |

| Letters retrieved: n (%) | 58 (72) | 58 (74) | 227 (87) |

| CMHT letters | |||

| Sample size: n | 80 | 78 | 85 |

| Letters retrieved: n (%) | 58 (72) | 62 (79) | 72 (85) |

Discussion

A combination of evidence-based dissemination and implementation strategies improved the quality of both GP and CMHT letters significantly during the project, and audit of administrative procedures suggested that reliability had also improved. Using and maintaining a combination of dissemination and implementation tools is more effective (Reference OxmanOxman, 1994) but, we discovered, also requires considerably more organisational skills than using one type of tool alone, particularly when large numbers of participants are involved. The extent of change achieved in the first year, considering the number of GPs and CMHT members we involved in the audit, lends support to the effectiveness of using more than one evidence-based implementation or dissemination tool to promote change in practitioners’ behaviour and decision-making.

By the end of the second year, as the ‘halo effect’ of the audit began to dim, a considerable proportion of letters still fell below the desired standards of quality and reliability; some gains made early on in the project had been lost, and administrative procedures remained unsatisfactory. We concluded that achieving more ‘seamless’ shared working between primary and secondary care will require much more than a protocol-based approach across the interface of the existing organisation of services towards more integrated working styles, models of care and treatment settings for GPs and CMHT practitioners.

Declaration of interest

None.

Acknowledgements

The authors want to thank Bharti Rao for her statistical advice in preparing this paper, and Professor Peter Tyrer for his comments on an earlier draft.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.