Introduction

The stigma of mental illness still affects the lives of most people with mental illness (Lasalvia et al., Reference Lasalvia, Zoppei, van Bortel, Bonetto, Cristofalo, Wahlbeck and Thornicroft2013; Thornicroft, Brohan, Rose, Sartorius, & Leese, Reference Thornicroft, Brohan, Rose, Sartorius and Leese2009). Over the last decade, the concept of an underlying continuum of mental illness and mental health has inspired numerous studies examining whether continuum beliefs can reduce mental illness stigma. Assuming a continuum from mental health to illness is coherent with current social and biological understanding (Goldberg, Reference Goldberg2000) and epidemiological findings. It corresponds to the dimensional classification of symptom severity in research criteria (ROC) and the use of thresholds of severity, frequency, and number of symptoms in current classifications such as DSM-5 and ICD-10. Similar to these classifications, for the purpose of this review, we define the term ‘mental illness’ broadly, including personality and substance use disorders (SUDs; Freeman, Reference Freeman2005).

A continuum concept of mental health and mental illness assumes one dimension from severe psychiatric symptoms to subclinical, light, or non-existent symptoms. Since every person is likely experiencing symptoms of mental illness at some points during their life, a person with mental illness might be seen as someone with similar, but more severe experiences, thus remaining ‘someone like us’. Continuum beliefs are framing how people perceive mental illness in general, they imply that someone's mental illness is not categorically distinct from normal behaviour but falls on a continuum of life experiences. Assumingly, continuum beliefs are amenable to interventions.

The opposite is a binary view of either mental health or mental illness, where people perceive the experience of mental illness to be fundamentally different from normal experiences and behaviour. Such categorical distinctions are, at a conceptual level, closely linked to the stigma process (Link & Phelan, Reference Link and Phelan2001; Tajfel & Turner, Reference Tajfel, Turner, Austin and Worchel1979; Turner & Oakes, Reference Turner and Oakes1986), which begins by creating groups and labelling them. Negative stereotypes are linked to labels, leading to separation of ‘us’ from ‘them’, status loss, and discrimination (Link & Phelan, Reference Link and Phelan2001). Mental illness stigma increases symptom burden, poses a barrier to help-seeking and fosters treatment avoidance (Angermeyer, van der Auwera, Carta, & Schomerus, Reference Angermeyer, van der Auwera, Carta and Schomerus2017; Clement et al., Reference Clement, Schauman, Graham, Maggioni, Evans-Lacko, Bezborodovs and Thornicroft2015; Eisenberg, Downs, Golberstein, & Zivin, Reference Eisenberg, Downs, Golberstein and Zivin2009; Henderson, Evans-Lacko, & Thornicroft, Reference Henderson, Evans-Lacko and Thornicroft2013; Schulze et al., Reference Schulze, Klinger-König, Stolzenburg, Wiese, Speerforck, van der Auwera-Palitschka and Schomerus2020). Since underlying categorical beliefs are central to the stigma process, continuum beliefs can be regarded as a counter of stigma at a conceptual level.

Literature on continuum beliefs and stigma has multiplied over the last few years. This systematic review and meta-analysis summarises correlation and intervention studies to establish whether continuum beliefs are in fact associated with less stigma, and whether continuum beliefs should be used for the de-stigmatisation of mental illness. We particularly want to find out:

(1) How are continuum beliefs and stigmatising attitudes towards people with mental illness associated? Are there differences in associations depending on the type of mental illness?

(2) Are continuum beliefs amenable to interventions? Are changes in continuum beliefs accompanied by changes in stigmatising attitudes? Do effects differ between types of mental illness?

Methodology

The study protocol was registered at PROSPERO as CRD42019123606 (available at https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?ID=CRD42019123606). The literature review was conducted following PRISMA guidelines (Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff, & Altman, Reference Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff and Altman2009).

Search strategy

A title, abstract, and keyword search combined the main topics: continuum beliefs, stigma, mental health, and illness using Boolean operators. For mental illness, the search contained both general terms (e.g. ‘mental disorder*’) and prevalent disorders (e.g. depress* OR alcohol*). Search strategy and topics have been reviewed using the PRESS checklist (McGowan et al., Reference McGowan, Sampson, Salzwedel, Cogo, Foerster and Lefebvre2016). Online Supplementary Appendix 1 contains search string and PICO questions.

The main search was conducted in January 2020 using PubMed, Web of Science, and PsycINFO with weekly e-mail alerts. Additional searches comprised of author correspondence and checking references lists. All eligible articles published before May 2020 were imported to Citavi 6 (Swiss Academic Software GmbH), automatically and manually removing any duplicates. The selection of articles was performed in a sequential manner based on pre-defined eligibility criteria (see below). First, articles dealing clearly with topics outside the scope of this review were eliminated through title screening (LJP, JK, and TG), followed by abstract (LJP) and full text screening (LJP and CS). In the screening stages of our review, we followed a liberal, over-inclusive approach, resolving all conflicts by consensus among four authors (LJP, CS, SS, and GS).

Eligibility criteria

Included articles had to be related to (1) continuum beliefs of mental health and mental illness (in general, or specific mental-, substance use-, or personality disorders) and (2) stigmatisation of people with mental illness (including attitudes, emotional reactions, or stereotypes). In addition to not meeting (1) and (2), the following exclusion criteria applied: (3) not containing primary data (e.g. reviews, comments, etc.); (4) unpublished articles; (5) not referring to human samples or (6) language other than English, German or French. Measures employed by the retrieved studies are described below (‘Results’ section).

Quality assessment

We assessed methodological quality using a modified version (see online Supplementary Appendix 2) of a 27 item-checklist originally developed to evaluate clinical intervention studies (Downs & Black, Reference Downs and Black1998) to allow a comparable risk of bias assessment. Two raters (LJP and CS) performed quality assessment independently; deviations were discussed with a third rater (SS).

Data extraction and coding

A coding protocol was pre-defined (Schewe, Hülsheger, & Maier, Reference Schewe, Hülsheger and Maier2014) containing study-, sample-, and effect size-level (see online Supplementary Appendix 1).

Analytic strategy

Several studies with similar predictor and outcome measures showed sufficient homogeneity to be aggregated into meta-analysis, which was the case for associations of continuum beliefs and social distance, emotional reactions (pro-social reaction, fear, and anger), and stereotypes (dangerousness, unpredictability, and responsibility). Results regarding interventions were only addressed narratively.

Meta-analyses were conducted using Meta-Essentials 1.5 (Suurmond, van Rhee, & Hak, Reference Suurmond, van Rhee and Hak2017). To be eligible for meta-analysis, studies needed to report either Pearson's correlation coefficients (r), unstandardised, or standardised (β) regression coefficients concerning the association of continuum beliefs and stigma-related outcomes. Due to differences between instruments, scale ranges, and study populations, random effects models were conducted (Riley, Higgins, & Deeks, Reference wRiley, Higgins and Deeks2011) with two-sided p values and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Heterogeneity was estimated via I 2 statistic, considering 25, 50, and 75% as thresholds of low, moderate, and high heterogeneity, respectively (Higgins, Thompson, Deeks, & Altman, Reference Higgins, Thompson, Deeks and Altman2003; Huedo-Medina, Sánchez-Meca, Marín-Martínez, & Botella, Reference Huedo-Medina, Sánchez-Meca, Marín-Martínez and Botella2006).

We used a widespread meta-analytic approach by Peterson and Brown (Reference Peterson and Brown2005), which suggests using r as effect-size and imputing missing r's using β (analyses of social distance, pro-social reaction, fear, and anger). Further analyses were undertaken with r as effect-size, without imputation (dangerousness, unpredictability, and responsibility).

However, there are methodological disadvantages to the imputation approach regarding comparability and estimation bias (Aloe, Reference Aloe2015; Roth, Le, Oh, van Iddekinge, & Bobko, Reference Roth, Le, Oh, van Iddekinge and Bobko2018). To address these, the results were compared with average effect-sizes estimated separately from r (bivariate or partial) and β (Rosenthal & DiMatteo, Reference Rosenthal and DiMatteo2001), if at least three studies were available. In the separate analyses (see online Supplementary Appendix 5), sensitivity analyses based on type of disorder and operationalisation were conducted. To assess publication bias, we conducted Funnel plots, Egger's regression, Trim and Fill procedure, and Fisher's Fail-Safe-N. Two subgroups of studies emerged based on common measures of continuum beliefs and analytic strategies [subgroup 1: one-item measure of continuum beliefs by Schomerus, Matschinger, and Angermeyer (Reference Schomerus, Matschinger and Angermeyer2013) using regression analyses; subgroup 2: items of Thibodeau (Reference Thibodeau2017, Reference Thibodeau and Peterson2018, Reference Thibodeau2019) or Wiesjahn, Brabban, Jung, Gebauer, and Lincoln (Reference Wiesjahn, Brabban, Jung, Gebauer and Lincoln2014), Wiesjahn, Jung, Kremser, Rief, and Lincoln, (Reference Wiesjahn, Jung, Kremser, Rief and Lincoln2016) using correlation analyses], prompting us to do additional analyses referring to these subgroups.

Results

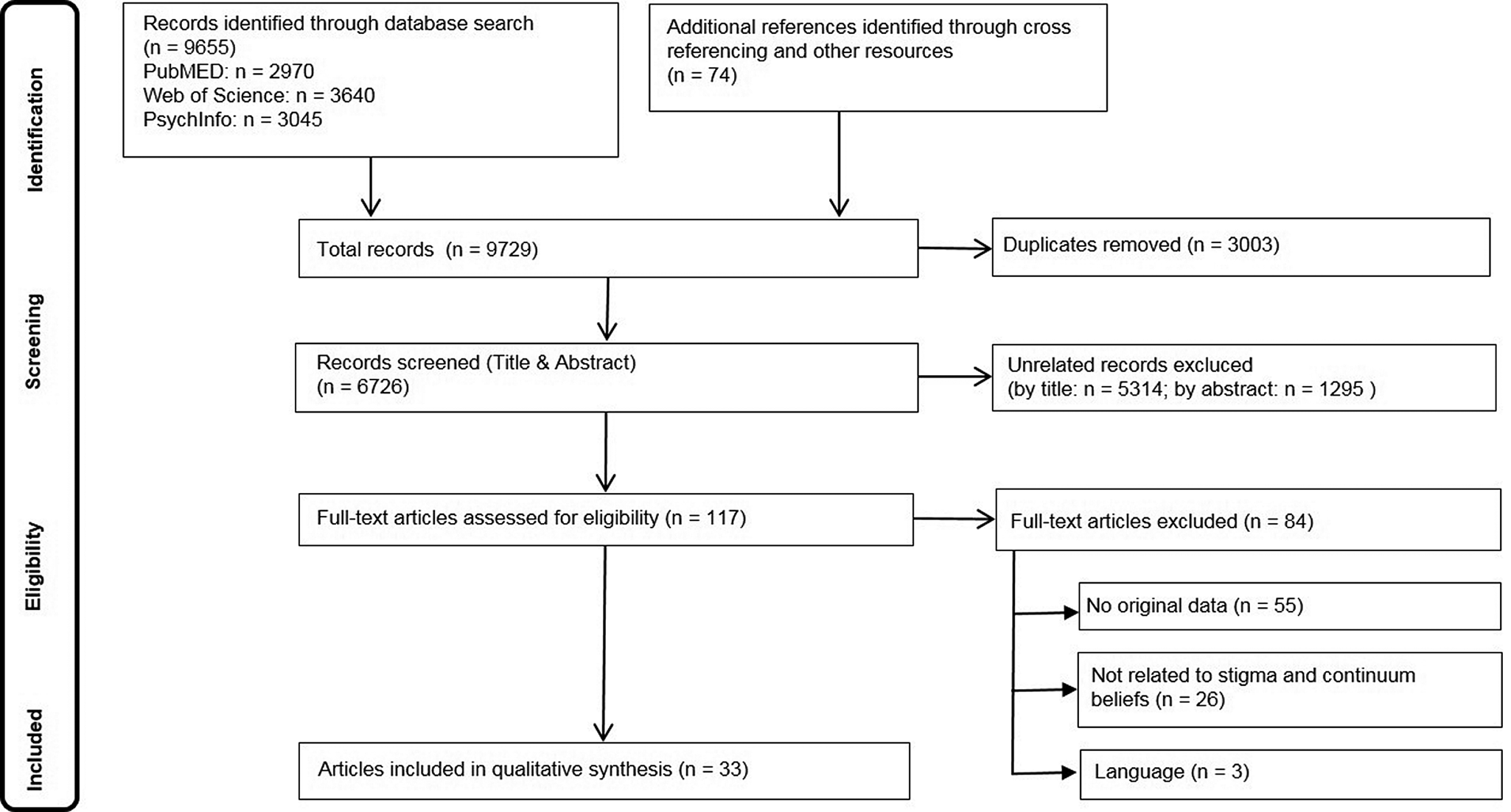

Altogether, N = 6726 unique articles were identified after electronic database search, cross-referencing, and removal of duplicates. A total of 6609 records were excluded through title and abstract screening. Excluded studies focused on medical stigma (Al-Hazmi, Reference Al-Hazmi2015; Cacioppo & Gardner, Reference Cacioppo and Gardner1993; Collins, Reference Collins2006), topics only loosely related to mental health and illness, like well-being (Aggarwal & Sriram, Reference Aggarwal and Sriram2018), classification issues (Casey et al., Reference Casey, Craddock, Cuthbert, Hyman, Lee and Ressler2013) or the continuum within categories of specific mental disorders (Andrulonis, Glueck, Stroebel, & Vogel, Reference Andrulonis, Glueck, Stroebel and Vogel1982). A total of 117 full text articles were retrieved for further consideration, of which 84 records were discarded (Fig. 1). A considerable part of these were reviews, not excluded earlier to identify original studies from the respective reference lists. None of the reviews focused on continuum beliefs and stigma.

Fig. 1. Flow chart of the review process.

Study characteristics

Descriptions of the included studies are provided in online Supplementary Appendix 3. Most studies were conducted in the United States (n = 10) and Germany (n = 12). Three studies were from Canada, two each were conducted in France and England, and one each in Singapore, the Netherlands, Ireland, and Japan. A total of 19 of the 33 studies originate from five research teams: Schomerus and Angermeyer (n = 6); Thibodeau (n = 4); Wiesjahn, Schlier, and Lincoln (n = 4); von dem Knesebeck and Makowski (n = 3); and Corrigan (n = 2). Twenty-five studies assessed attitudes of the general population and/or mental health professionals, experts, caregivers, etc. (n = 7) and/or people with mental illness (n = 4). Attitudes were assessed towards schizophrenia/psychosis (n = 19), depression (n = 11), alcohol use disorder (n = 3), obsessive-compulsive disorder (n = 2), posttraumatic stress disorder (n = 1), bipolar disorder (n = 1), and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (n = 1) or mental illness in general (n = 6). Although there was no specific timeframe for eligibility, 27 of the included articles were published since 2015, thus attesting to the high actuality of the research field. The earliest included study was from 1957 (Cumming & Cumming, Reference Cumming and Cumming1957), thus being the only included article published before 2003.

Results of methodological quality assessment

The modified version of Downs & Black Quality Assessment (see online Supplementary Appendix 2) revealed an overall quality between 47% (Cumming & Cumming, Reference Cumming and Cumming1957) and 100% (Speerforck et al., Reference Speerforck, Stolzenburg, Hertel, Grabe, Strauß, Carta and Schomerus2019) with 17 studies scoring 80% or higher.

Assessment of continuum beliefs and stigma

Continuum beliefs were most frequently assessed with regards to case vignettes depicting a person with mental illness (18 out of 33 studies). Other methods included continuum beliefs elicited after other experimental manipulations (n = 4), surveys without using a vignette (n = 2), and qualitative studies (n = 3). Six intervention studies did not specifically measure continuum beliefs.

An easy to administer and simple measure to operationalise continuum beliefs (Schomerus et al., Reference Schomerus, Matschinger and Angermeyer2013) was used in eight studies: after having read a case vignette, respondents were asked to indicate their agreement with the following statement on Likert scales: ‘Basically we are all sometimes like [person X]. It is just a question how pronounced this state is’. Speerforck et al. (Reference Speerforck, Stolzenburg, Hertel, Grabe, Strauß, Carta and Schomerus2019) added the aspect of ‘abnormality’: ‘All in all the problem of this person is abnormal’.

The 16-item Continuum Beliefs Questionnaire (CBQ; Wiesjahn et al., Reference Wiesjahn, Brabban, Jung, Gebauer and Lincoln2014) emphasises the normalcy of psychotic symptoms and was used in six studies, including a revised (Schlier, Scheunemann, & Lincoln, Reference Schlier, Scheunemann and Lincoln2016) and an adapted version (Violeau, Valery, Fournier, & Prouteau, Reference Violeau, Valery, Fournier and Prouteau2020). Thibodeau's assessment of continuum and categorical beliefs with varying numbers of items was used in five studies. Two studies used or adapted the Similar-Different-Scale (Corrigan, Bink, Fokuo, & Schmidt, Reference Corrigan, Bink, Fokuo and Schmidt2015) and one study each used the Continuity with Normal Experience Scale (Norman, Windell, & Manchanda, Reference Norman, Windell and Manchanda2012) and the Problem Drinking Belief Scale (Morris, Albery, Heather, & Moss, Reference Morris, Albery, Heather and Moss2020).

Indicating a shared conceptualisation of stigma, the most frequently used measure of stigma is the Social Distance Scale (Link, Cullen, Frank, & Wozniak, Reference Link, Cullen, Frank and Wozniak1987), assessing the desire to avoid people with certain characteristics in different social situations. Another commonly used scale is the Emotional Reactions to People with Mental Illness Scale (Angermeyer & Matschinger, Reference Angermeyer and Matschinger2003b; Angermeyer, Holzinger, & Matschinger, Reference Angermeyer, Holzinger and Matschinger2010), with subscales indicating pro-social reactions, fear, and anger. Measurement of stereotypes was more heterogeneous, with frequently [Stereotypes about Schizophrenia (Angermeyer & Matschinger, Reference Angermeyer and Matschinger2004); Semantic Differential Tool (Olmsted & Durham, Reference Olmsted and Durham1976)] and rarely used inventories [Perceived Dangerousness Scale (Link et al., Reference Link, Cullen, Frank and Wozniak1987), Explicit Measure of Self-Stereotype Association (Violeau et al., Reference Violeau, Valery, Fournier and Prouteau2020)] and also heterogeneous subscales (dangerousness and/or unpredictability and responsibility/blame).

Associations between continuum beliefs and stigma

Seven cross-sectional and six intervention studies investigate the associations between continuum beliefs and stigma-related outcomes. Relevant information was added by two qualitative studies, which mention the belief of similarity (‘they are folks just like us’) as a counter factor to stigma (Schoech, 2017). Interviewees explained a way to reduce social distance ‘is by understanding human experience as a continuum. This idea challenges the border between what's normal and abnormal by emphasizing that the difference is based on degrees, not absolute differences’ (Alvarado Chavarría, Reference Alvarado Chavarría2000, p. 94).

Several studies report a percentage of agreement to the continuum beliefs statement (‘Basically we are all sometimes like this person. It is just a question how pronounced this state is.’), collapsing the Likert-scale answers on each side of the midpoint into ‘agree’ and ‘disagree’ categories. For depression, 42–58% agreed with the continuum statement, while 14–25% disagreed; for schizophrenia only one in three persons agreed, while 40–50% disagreed (Angermeyer et al., Reference Angermeyer, Millier, Rémuzat, Refaï, Schomerus and Toumi2015; Schomerus et al., Reference Schomerus, Matschinger and Angermeyer2013; Subramaniam et al., Reference Subramaniam, Abdin, Picco, Shahwan, Jeyagurunathan, Vaingankar and Chong2017). For ADHD, more than six times as many people agreed than disagreed (Speerforck et al., Reference Speerforck, Stolzenburg, Hertel, Grabe, Strauß, Carta and Schomerus2019); for alcohol use disorder, agreement rates were around one-third, while slightly more than 40% disagreed (Schomerus et al., Reference Schomerus, Matschinger and Angermeyer2013; Subramaniam et al., Reference Subramaniam, Abdin, Picco, Shahwan, Jeyagurunathan, Vaingankar and Chong2017). Hence, type of disorder proved relevant for the general population in perceiving disorders as relating with their own experiences to a varying degree. Concerning age and education, results are mixed with no clear tendency (Angermeyer et al., Reference Angermeyer, Millier, Rémuzat, Refaï, Schomerus and Toumi2015; Schomerus et al., Reference Schomerus, Matschinger and Angermeyer2013; Speerforck et al., Reference Speerforck, Stolzenburg, Hertel, Grabe, Strauß, Carta and Schomerus2019; Subramaniam et al., Reference Subramaniam, Abdin, Picco, Shahwan, Jeyagurunathan, Vaingankar and Chong2017).

Overall effects

Table 1 shows an overview of meta-analytic findings for social distance (see also Table 2), emotional reactions (pro-social reactions, fear, and anger), and stereotypes (dangerousness, unpredictability, and responsibility). The combined correlation of continuum beliefs with stigmatising attitudes was mostly significant in the expected directions, with the exception of anger and responsibility, which were only significant for subgroups. Heterogeneity ranged from I 2 = 0.00% to 91.86%. Analyses including only studies with similar operationalisation were less heterogeneous, indicating the influence of methodological differences. Heterogeneity was especially lower for ‘subgroup 2’, containing correlations and measures of Wiesjahn et al. and Thibodeau et al. Operationalisation also explained more heterogeneity than type of disorder. This pattern of results was even more apparent in the separate analyses of correlation and regression coefficients for social distance and pro-social reactions. Publication bias analyses did not indicate substantial bias. See online Supplementary Appendix 4 for meta-analyses of emotional reactions and stereotypes and online Supplementary Appendix 5 for separate meta-analyses.

Table 1. Overview of meta-analyses on the association of continuum beliefs and stigmatising attitudes (social distance, pro-social reactions, fear, anger, dangerousness, unpredictability, and responsibility)

Notes. Outcome: overall results and subgroup analyses (type of disorder: depression, schizophrenia; methods: subgroup 1 = one-item measure of Schomerus et al., Reference Schomerus, Matschinger and Angermeyer2013, regression models; subgroup 2 = Thibodeau's/Wiesjahn's operationalisation, correlation models). k, number of effect-sizes; r, combined correlation coefficient, significant correlations highlighted in bold; p, two-tailed p value of combined r. L CI/U CI, lower and upper limit of confidence interval. I 2, heterogeneity. Meta-analytic results of imputation method (Peterson & Brown, Reference Peterson and Brown2005).

a = no imputation method, r as effect-sizes.

Table 2. Meta-analysis and forest plot of the association of continuum beliefs and social distance (single study effect sizes and combined effect-size)

Notes: Population: 1 = general population, 2 = undergraduates; Disorder: Depr., depression; Schiz., schizophrenia; Alc., alcoholism; ADHD, attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder; Dement., dementia; OCD, obsessive-compulsive disorder; r, correlation coefficient; L CI/U CI, lower and upper limit of confidence interval. Weight, study weight. Forest plot: single study effect-sizes and combined effect-size with CI. Size of point reflects study weight.

Social distance

The overall correlation was significant: r = −0.17 (CI −0.22 to −0.12) indicating a small negative association. The subgroup analysis regarding type of disorder indicated a significant negative correlation particularly for schizophrenia (r = −0.22, CI −0.28 to −0.14). Most studies (Table 2) found consistent negative associations, except for an undergraduate (Thibodeau, Shanks, & Smith, Reference Thibodeau, Shanks and Smith2018), dementia, and depression sample (Subramaniam et al., Reference Subramaniam, Abdin, Picco, Shahwan, Jeyagurunathan, Vaingankar and Chong2017).

The separate meta-analyses of r and β (r p) indicated significant effect-sizes from r = −0.19 to −0.24 and from r p = −0.07 to −0.10. Heterogeneity was lower in the meta-analyses of r compared to β (r p). Subgroup analyses of Thibodeau's studies showed that applying a similar operationalisation yields homogeneous correlational estimates (I 2 = 00.00). Partial correlational estimates, in contrast, were more homogeneous when different types of disorders were analysed separately.

Emotional reactions

Regarding the association with pro-social reactions, a significant positive correlation of r = 0.15 (CI 0.01–0.28) was found overall. Subgroup analyses regarding type of disorder were significant for depression, r = 0.21 (CI 0.08–0.34). Single effect-sizes vary from a majority of small positive correlations to three small and moderate negative correlations (Thibodeau, Reference Thibodeau2017; Thibodeau et al., Reference Thibodeau, Shanks and Smith2018; Thibodeau & Peterson, Reference Thibodeau and Peterson2018).

Two separate meta-analyses produced non-significant correlations. Sensitivity analyses showed more homogenous results for similar operationalisation. The partial correlation meta-analysis (r p = 0.10) included different types of disorders, but with similar operationalisation and was homogenous.

Overall, fear was weakly negatively associated with continuum beliefs (Angermeyer et al., Reference Angermeyer, Millier, Rémuzat, Refaï, Schomerus and Toumi2015; Makowski, Mnich, Angermeyer, & von dem Knesebeck, Reference Makowski, Mnich, Angermeyer and von dem Knesebeck2016a), yielding a significant combined correlation of r = −0.07 (CI −0.11 to −0.03). Subgroup analyses were significant for schizophrenia (r = −0.12, CI −0.17 to −0.06).

Regarding anger, results vary from significant small positive associations for depression and schizophrenia (Schomerus et al., Reference Schomerus, Matschinger and Angermeyer2013), a significant positive association for schizophrenia, but not for depression (Angermeyer et al., Reference Angermeyer, Millier, Rémuzat, Refaï, Schomerus and Toumi2015), to non-significant associations (Makowski et al., Reference Makowski, Mnich, Angermeyer and von dem Knesebeck2016a). The combined effect size of r = −0.05 (CI −0.01 to 0.10) is insignificant as well as subgroup analyses regarding type of disorder.

Stereotypes

Dangerousness (r = −0.12, CI −0.21 to −0.02) and unpredictability (r = −0.18, CI −0.28 to −0.08) were overall small, but significantly and negatively correlated with continuum beliefs. These analyses are almost exclusively based on studies about schizophrenia. Heterogeneity was low for analyses with comparable methods in subgroup 2. The combined correlation for responsibility also yielded significance (r = −0.10, CI −0.11 to −0.09) and low heterogeneity, when only studies about schizophrenia were combined (Table 1).

Intervention studies

Eight studies examined the effects of broader interventions, e.g. a mental health awareness campaign (Makowski et al., Reference Makowski, Mnich, Ludwig, Daubmann, Bock, Lambert and von dem Knesebeck2016b) or school-based project (Schulze, Richter-Werling, Matschinger, & Angermeyer, Reference Schulze, Richter-Werling, Matschinger and Angermeyer2003) that explicitly used continuum messages, but also included others. Four of these studies focused on attitudes of professionals, one additional analysis of expert ratings did not specifically recommend continuum messages (Clement, Jarrett, Henderson, & Thornicroft, Reference Clement, Jarrett, Henderson and Thornicroft2010). A programme for first responders found significant decreases in stigma combined across different sites (Dobson, Szeto, & Knaak, Reference Dobson, Szeto and Knaak2019; Szeto, Dobson, & Knaak, Reference Szeto, Dobson and Knaak2019). A psychoeducational therapy for caregivers (Shiraishi, Watanabe, Katsuki, Sakaguchi, & Akechi, Reference Shiraishi, Watanabe, Katsuki, Sakaguchi and Akechi2019) and a workshop for mental health professionals found no significant effects on stigma (Helmus, Schaars, Wierenga, Glint, & van Os, Reference Helmus, Schaars, Wierenga, Glint and van Os2019).

Studies investigating attitudes of general population samples could at least partially reduce stigma (Makowski et al., Reference Makowski, Mnich, Ludwig, Daubmann, Bock, Lambert and von dem Knesebeck2016b; Schulze et al., Reference Schulze, Richter-Werling, Matschinger and Angermeyer2003), with the exception of Cumming and Cumming (Reference Cumming and Cumming1957). Since those studies did not, however, specifically manipulate continuum beliefs, any change in stigma that is attributable to altering continuum beliefs cannot exactly be determined.

Eleven studies investigated effects of specifically manipulating continuum beliefs and target attitudes of general population samples. In these studies, an unlabelled vignette fulfilling criteria of a mental illness is presented. The experimental manipulation typically consists of additional intervention texts (e.g. bogus scientific article and magazine article) or video, either presenting evidence for a continuum model or for distinct differences between mental health and illness, and a third neutral condition is used as a control. Table 3 contains an overview of stigma-related outcomes of continuum interventions compared to control conditions. All but one experimental manipulation did successfully change self-reported continuum beliefs in the intended way. Two studies found reduced desire for social distance in the continuum- compared to control conditions: β = 0.175, p = 0.003, reverse coded (Schomerus et al., Reference Schomerus, Angermeyer, Baumeister, Stolzenburg, Link and Phelan2016); F (2,175) = 3.21, p = 0.02 (Cole & Warman, Reference Cole and Warman2019). Furthermore, Thibodeau et al. (Reference Thibodeau, Shanks and Smith2018) found a marginal reduction compared to control, F (1,66) = 3.14, p < 0.09, η p2 = 0.05, and a significant reduction compared to categorical condition. Four other studies did not find significant effects.

Table 3. Effects of intervention studies

Continuum belief intervention in comparison with the control group.

Notes: CB, continuum Belief; SDS, Social Distance Scale; Diff., difference measures; Unpred., unpredictability; Pro-Social, pro-social reactions; ▴, significant increase; ▾, significant decrease; ◊, no significant findings.

a No direct stigma measures.

Perceptions of difference were lower in the continuum- compared to neutral or categorical conditions in three studies. For negative stereotypes, results are inconsistent. There were significant effects on unpredictability: CB: M = 5.5, Control: M = 4.43, t (359) = 3.24, p = 0.004 (Violeau et al., Reference Violeau, Valery, Fournier and Prouteau2020), as well as compared to categorical (Thibodeau et al., Reference Thibodeau, Shanks and Smith2018) and biogenetic conditions (Wiesjahn, Jung, Kremser, Rief, & Lincoln, Reference Wiesjahn, Jung, Kremser, Rief and Lincoln2016). For dangerousness, effects have been found pre to post, t (58) = 3.10, p = 0.003 (Cole & Warman, Reference Cole and Warman2019), as well as compared to the categorical condition (Thibodeau et al., Reference Thibodeau, Shanks and Smith2018).

For blame Schomerus et al. (Reference Schomerus, Angermeyer, Baumeister, Stolzenburg, Link and Phelan2016) found a decrease compared to control group (β = −0.178, p = 0.05), while other studies found no effects or even an increase in blame compared to the categorical condition (Wiesjahn et al., Reference Wiesjahn, Jung, Kremser, Rief and Lincoln2016).

No positive effects were found for emotional reactions (pro-social, fear, and anger). On the contrary, there was a significant main effect for condition for within category assimilation anger (F (2,150) = 5.44, p = 0.005; Dolphin and Hennessy, Reference Dolphin and Hennessy2017) and an increase in fear compared to the control group (F (1,118) = 5.73, p = 0.018, η p2 = 0.05; Thibodeau and Peterson, Reference Thibodeau and Peterson2018). Compared to the categorical group, less pro-social reactions were found (Thibodeau et al., Reference Thibodeau, Shanks and Smith2018), but most studies reported no significant changes (Table 3).

Regarding studies about persons with mental illness, Thibodeau (Reference Thibodeau2019) investigated attitudes of people with self-reported depression and found no significant intervention effects on depression stigma. Beyond stigmatising attitudes, Morris et al. (Reference Morris, Albery, Heather and Moss2020) found a continuum intervention on alcohol use disorder to improve problem recognition of the respondents' own heavy drinking.

To sum up, there is evidence of successful manipulations of continuum beliefs, but mixed evidence concerning changes in stigma through manipulation of continuum beliefs with no apparent tendency regarding the type of investigated mental illness. Evidence is scant for groups other than the general population. We will discuss how methodological differences between studies might have contributed to these seemingly contradictory outcomes.

Discussion

This is the first systematic review and meta-analysis to investigate the associations of continuum beliefs of mental health and illness with mental health stigma, demonstrating that continuum beliefs are generally associated with lower desire for social distance, lower perception of dangerousness and unpredictability as well as less fear and more pro-social reactions.

Until now, continuum beliefs have most frequently been assessed with regards to depression and schizophrenia, with higher general agreement to continuum beliefs for depression. Associations between continuum beliefs and stigma are similar for all investigated types of disorders, but also show illness-related differences. For schizophrenia, findings are most consistent throughout all conducted meta-analyses. For depression, continuum beliefs are significantly associated with more pro-social reactions. The lack of associations with social distance or fear in depression could represent a ceiling effect. Associations are most robust where stigma is most severe (Angermeyer & Matschinger, Reference Angermeyer and Matschinger2003a, Reference Angermeyer and Matschinger2003b). Future studies might add on by adapting stigma measures to the investigated mental illness, facets of stigma play different roles in different disorders.

Regarding intervention studies, experimental designs are successfully manipulating continuum beliefs, but this is inconsistently accompanied by changes in stigma. Since few studies showed insignificant or even opposite findings, with some continuum interventions increasing stigma, the question arises which methodological differences are responsible for these divergent findings.

One general difference appears to be whether respondents are encouraged to see themselves on a continuum, or if they are asked (or instructed) about a continuum in more general terms, without reference to themselves. This seems to echo through operationalisation as well as design of interventions. To what extent respondents perceive people with mental illness as in-group or out-group (Tajfel & Turner, Reference Tajfel, Turner, Austin and Worchel1979) while they complete questionnaires and interventions might influence self-reported stigma.

Continuum beliefs can be elicited by establishing a personal connection between respondents and vignette character. This is exemplified in the item ‘Basically we are all sometimes like this person. It is just a question how pronounced this state is’ (Schomerus et al., Reference Schomerus, Matschinger and Angermeyer2013). By suggesting similarity between ‘us’ and ‘them’, it measures the respondent's willingness to accept the depicted person as one of ‘us’. Studies using this type of operationalisation generally show results in line with the hypotheses. Alternatively, continuum beliefs can be framed in more general terms, as a continuum between a state of illness and normalcy, not directly involving the respondents. Along this line, Thibodeau's set of items contain more general descriptions not including the respondent (e.g. ‘People who have schizophrenia have symptoms [delusions, hallucinations] that are similar to the occasional experiences of ordinary people’). Therefore, these items can be answered affirmatively, even if people with mental illness are regarded as an out-group, probably leading to more heterogeneous results. Our review suggests that personally relating respondents to a continuum, rather than informing them on the concept, could be crucial to using continuum messages for de-stigmatisation.

Manipulations of intervention studies are prominently text-based, which is of high internal validity and can easily be implemented into online surveys. Undergoing efforts to further improve continuum interventions, by designing audio-visual vignettes (Corrigan et al., Reference Corrigan, Bink, Fokuo and Schmidt2015, Reference Corrigan, Schmidt, Bink, Nieweglowski, Al-Khouja, Qin and Discont2017; Dolphin & Hennessy, Reference Dolphin and Hennessy2017; Morris et al., Reference Morris, Albery, Heather and Moss2020), or extending the intervention to more time points (Corrigan et al., Reference Corrigan, Bink, Fokuo and Schmidt2015; Thibodeau, Reference Thibodeau2019; Thibodeau et al., Reference Thibodeau, Shanks and Smith2018) are likely to improve personal involvement of the respondent as well. Personal contact and the inclusion of lived experiences had positive effects (Hansson, Stjernswärd, & Svensson, Reference Hansson, Stjernswärd and Svensson2016). Corrigan et al. (Reference Corrigan, Schmidt, Bink, Nieweglowski, Al-Khouja, Qin and Discont2017) combined these factors into a video intervention connoting personal contact to a person with schizophrenia. Other factors to improve identification could involve the gender of the vignette character (Angermeyer et al., Reference Angermeyer, Millier, Rémuzat, Refaï, Schomerus and Toumi2015), as well as cultural, ethnic, and national characteristics (Corrigan, Reference Corrigan2004). Certainly, face-to-face contact would improve the respondent's personal involvement (Thibodeau, Reference Thibodeau2019), however, our results indicate that text- or video-based interventions are also capable of promoting a continuum of mental health and illness which includes the respondents and encourages them to view people with mental illness as in-group. In line with that, studies should focus on further developing even more identifiable and involving interventions. Various promising e-mental-health approaches have been detected to increase engagement and improve identification with fictional characters (Feltz, Forlenza, Winn, & Kerr, Reference Feltz, Forlenza, Winn and Kerr2014; Igartua & Frutos, Reference Igartua and Frutos2017). The most seminal approach to improve engagement is gamification, where game elements such as avatars, storylines, and rewarding feedback are implemented into non-game contexts (Looyestyn et al., Reference Looyestyn, Kernot, Boshoff, Ryan, Edney and Maher2017; Miller & Polson, Reference Miller and Polson2019; Sardi, Idri, & Fernández-Alemán, Reference Sardi, Idri and Fernández-Alemán2017; Schwarz, Huertas-Delgado, Cardon, & DeSmet, Reference Schwarz, Huertas-Delgado, Cardon and DeSmet2020). Current virtualisation and digitalisation should be appreciated to create personally involving, virtual contact interventions and foster perceptions of people with mental illness as being in-group and by that improve attitudes towards mental illness.

Methodological considerations

Our review shows that continuum beliefs and stigma have mostly been examined for only two disorders, depression and schizophrenia, while investigation of other disorders such as SUD is only beginning. Also, most studies are from two countries only, so any conclusions are limited to the disorders and countries studied.

In this emerging field, we aimed to arrive at a comprehensive review of literature, also including interventions not primarily focusing on continuum beliefs. However, it is likely that more interventions might have promulgated a continuum model of mental health and illness, but without explicitly mentioning it or including appropriate measures, they could not be included in the review. We did not establish formal reliability of our screening of articles but aimed at being over-inclusive in the screening stage and resolving all conflicts regarding eligibility among four of the authors based on the full texts.

Low initial stigma prior to the interventions could have caused a ceiling effect and needs to be considered as a reason for low effect-sizes (Schulze et al., Reference Schulze, Richter-Werling, Matschinger and Angermeyer2003; Shiraishi et al., Reference Shiraishi, Watanabe, Katsuki, Sakaguchi and Akechi2019). Most available studies obtained subjective information through self-ratings. Participants rarely state negative attitudes, especially if stigma reduction is the obvious study aim (Helmus et al., Reference Helmus, Schaars, Wierenga, Glint and van Os2019). Almost all included articles discuss social desirability and resulting limited validity. Nevertheless, studies that record attitudes through implicit assessment (Schlier & Lincoln, Reference Schlier and Lincoln2019) or measurable behaviour, e.g. seating distance (Thibodeau, Reference Thibodeau2017), are exceptions.

The included studies show high heterogeneity, contain real variance (Borenstein, Reference Borenstein2009) and need to be considered inconsistent. To account for high I 2, three explanations are suggested: (a) methodological subgroups, (b) choice of effect measures, and (c) clinically important subgroups (Higgins et al., Reference Higgins, Thompson, Deeks and Altman2003). (a) In our analyses, methodological differences (workgroups, questionnaires, etc.) explain heterogeneity best. (b) Regarding statistical methods, imputing β into r-meta-analysis might have introduced variance, because β usually contains influences of covariates. The use of two different meta-analytic approaches enables us to understand our data the best: separate meta-analyses of studies reporting r or β yielded valuable information (Aloe, Reference Aloe2015). Lower heterogeneity in separate meta-analyses compared to using (imputed) r lead to the finding that heterogeneity is not completely inherent to the study contents but partly due to statistical methods. (c) Subgroup and sensitivity analyses regarding the type of disorder explained rather little heterogeneity. Interpretation needs to be done with caution due to the low number of studies (Thompson & Higgins, Reference Thompson and Higgins2002). We established a measure of methodological quality but did not add it as a covariate to our analyses. Methodological quality is generally sensitive to bias in the selection of criteria and coding, and mostly limited to the published content of the paper (Higgins & Green, Reference Higgins and Green2011). Also, moderator analyses are sensitive to selection of articles (Van Rhee, Suurmond, & Hak, Reference Van Rhee, Suurmond and Hak2015), so we considered methodological quality at present more suitable for narrative rather than statistical analyses.

Based on findings so far, future investigations should focus on the following: first, a theoretically based investigation of further influencing variables such as previous contact, age, or gender seems necessary. Second, continuum beliefs should be tested in relation to the construct of social identity (Tajfel & Turner, Reference Tajfel, Turner, Austin and Worchel1979; Turner & Oakes, Reference Turner and Oakes1986), to investigate perceptions of in-/out-group together with continuum belief interventions. Finally, to further improve interventional outcomes, the effects of different interventions should be assessed with special focus on how respondents are personally involved with the concept of a continuum. Digital- and gamification interventions, long-term interventions and the comparison regarding types of mental disorders should be considered to create even more effective interventions reducing stigma and improving help-seeking.

In summary, continuum beliefs can be acknowledged as beneficial to be included in anti-stigma campaigns and interventions with promising effects on subsequent health-related outcomes. Certainly, continuum beliefs alone will not be able to solve the problem of mental health-related stigma, yet might be able to provide an inclusive and promising foundation for other intervention messages. Therefore, we regard it a contemporary and necessary conclusion to include the concept of continuum beliefs into future study on destigmatising mental illness.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291721000854

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge Samin Schlick (University of Greifswald, Institute of Psychology, Department of Health and Prevention), Johanna Kummetat and Tobias Gfesser (Leipzig University, Medical Faculty, Department of Psychiatry and Psychotherapy) for their work in the screening process of the systematic review.

Financial support

The study was supported by DFG Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (GS, grant number SCHO 1337/4-2; SS, grant number SCHM 2683/4-2).

Conflict of interest

None.