Introduction

Approximately one-third of patients with schizophrenia display suboptimal response to two trials of non-clozapine antipsychotic medication and are termed treatment resistant (Elkis, Reference Elkis2007; Howes et al., Reference Howes, McCutcheon, Agid, de Bartolomeis, van Beveren, Birnbaum and Correll2017). Treatment resistant patients face poorer prognosis and functioning than those whose symptoms respond to antipsychotic treatment (Iasevoli et al., Reference Iasevoli, Giordano, Balletta, Latte, Formato, Prinzivalli and de Bartolomeis2016; Kennedy, Altar, Taylor, Degtiar, & Hornberger, Reference Kennedy, Altar, Taylor, Degtiar and Hornberger2014; Land et al., Reference Land, Siskind, McArdle, Kisely, Winckel and Hollingworth2017). Consequently, management of this patient group consumes a disproportionately large share of the total cost of schizophrenia care (Andrews, Knapp, McCrone, Parsonage, & Trachtenberg, Reference Andrews, Knapp, McCrone, Parsonage and Trachtenberg2012; Kennedy et al., Reference Kennedy, Altar, Taylor, Degtiar and Hornberger2014). Clozapine is the only licensed pharmacotherapy for treatment resistant schizophrenia and is uniquely associated with better outcomes, although response to clozapine is variable (Kane, Honigfeld, Singer, & Meltzer, Reference Kane, Honigfeld, Singer and Meltzer1988; NICE, 2014; Siskind, McCartney, Goldschlager, & Kisely, Reference Siskind, McCartney, Goldschlager and Kisely2016; Tiihonen et al., Reference Tiihonen, Lönnqvist, Wahlbeck, Klaukka, Niskanen, Tanskanen and Haukka2009).

Due to risk of adverse effects and monitoring requirements, and as the degree of therapeutic response to clozapine can only be determined through a trial of treatment, initiation of clozapine may be delayed in favour of poorly evidenced high dosage or polypharmacy strategies (Bachmann et al., Reference Bachmann, Aagaard, Bernardo, Brandt, Cartabia, Clavenna and Taylor2017; Gee, Shergill, & Taylor, Reference Gee, Shergill and Taylor2016; Kadra et al., Reference Kadra, Stewart, Shetty, Downs, MacCabe, Taylor and Hayes2016; Lally & MacCabe, Reference Lally and MacCabe2015; Nielsen, Dahm, Lublin, & Taylor, Reference Nielsen, Dahm, Lublin and Taylor2010). According to almost all international guidelines, patients are defined as treatment resistant and thereby eligible for a trial of clozapine after failing to respond to at least two antipsychotics. These criteria can theoretically be met as soon as two months after illness onset, yet the average delay in clozapine initiation is estimated at approximately four years in the UK (Howes et al., Reference Howes, Vergunst, Gee, McGuire, Kapur and Taylor2012, Reference Howes, McCutcheon, Agid, de Bartolomeis, van Beveren, Birnbaum and Correll2017). Understanding the factors associated with variability in clozapine response could therefore help to optimise clinical treatment algorithms. This is particularly pertinent given evidence that (1) the majority of treatment-resistant patients have a suboptimal response to antipsychotic medication from illness onset (Lally et al., Reference Lally, Ajnakina, Di Forti, Trotta, Demjaha, Kolliakou and Murray2016); (2) when patients fail to reach remission after a first antipsychotic trial, switching to a second non-clozapine antipsychotic does not increase the likelihood of remission (Kahn et al., Reference Kahn, Winter van Rossum, Leucht, McGuire, Lewis, Leboyer and Wilson2018) and (3) duration of inadequate treatment, and thereby active symptoms, is associated with poorer long-term outcomes (Marshall et al., Reference Marshall, Lewis, Lockwood, Drake, Jones and Croudace2005).

Accurate prediction of clozapine response holds potential for patient stratification in clinical trials of early clozapine use and clinical decision making. Currently, no biomarkers of clozapine response with sufficient reproducibility or predictive accuracy for clinical application have been identified (Samanaite et al., Reference Samanaite, Gillespie, Sendt, McQueen, MacCabe and Egerton2018). Clinical and demographic variables could supplement biomarker data in the development of prediction models and inform biomarker research by highlighting confounding variables to be considered in analyses. A previous review found no consistent associations between clinical and demographic variables and clozapine response (Suzuki, Uchida, Watanabe, & Kashima, Reference Suzuki, Uchida, Watanabe and Kashima2011). As this was performed almost a decade ago, an update of the literature is required. The aim of this review was to identify clinical and demographic factors associated with variance in response to clozapine.

Methods

This review was performed and reported within PRISMA guidelines (Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff, Altman, & PRISMA, Reference Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff and Altman2009; online Supplementary materials 2), following a pre-registered protocol (PROSPERO: CRD42019138119).

Search strategy

A PubMed search restricted to titles and abstracts was conducted on 20 March 2020 using search terms ‘schizophrenia’ or ‘treatment-resistant schizophrenia’ or ‘treatment-refractory schizophrenia’ and ‘clozapine’ and ‘response’ or ‘outcome’, with filters set to English language studies on human participants. Titles and abstracts returned from the search were screened for inclusion and exclusion criteria. Articles considered potentially eligible were full text screened. Reference lists of articles meeting inclusion criteria were hand-searched, and all non-duplicate potential papers were full text screened.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Studies published in peer reviewed journals were included if they reported a relationship between any clinical or demographic variable and response to clozapine. Study designs using prospective, retrospective and cross-sectional ascertainment of clozapine response were all included if demographic and clinical measures were available from the time period immediately before clozapine initiation. To capture the complexity of therapeutic response, we included articles that used clinical, service use and functional measures of clozapine response, whether reported as categorical or continuous outcome variables. All-cause discontinuation of clozapine was not an eligible outcome measure because factors other than lack of efficacy may contribute to cessation of clozapine treatment (Legge et al., Reference Legge, Hamshere, Hayes, Downs, O'Donovan, Owen and MacCabe2016; Üçok et al., Reference Üçok, Yağcıoğlu, Yıldız, Kaymak, Saka, Taşdelen and Şenol2019). The meta-analysis included a subset of articles where clozapine response was defined as symptomatic improvement on clinical rating scales (see Section ‘Meta-analysis’). We included studies that allowed concurrent treatment with other pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions, because this reflects clinical practice. Studies were excluded if treatment response was only compared between groups treated with clozapine v. clozapine-plus-augmentation.

Inclusion required that the publication reported on participants with a diagnosis of schizophrenia, schizophreniform disorder, schizoaffective disorder and/or psychotic disorder (ICD-10 F20-F29). Studies were excluded if they focused on mood disorders (ICD-10 F30-F39) because the concept of treatment resistance in this cohort may involve resistant mood symptoms, as well as psychosis (Gitlin, Reference Gitlin2001; Hui Poon, Sim, & Baldessarini, Reference Hui Poon, Sim and Baldessarini2015). Studies were also excluded if their focus was on childhood onset schizophrenia (<18 years) due to differential risk factors, relative rarity and frequent misdiagnosis of affective disorders within this patient cohort (Driver, Gogtay, & Rapoport, Reference Driver, Gogtay and Rapoport2013; Driver, Thomas, Gogtay, & Rapoport, Reference Driver, Thomas, Gogtay and Rapoport2020; Rapoport & Gogtay, Reference Rapoport and Gogtay2011). Studies were excluded if important data were omitted or insufficient methodological or statistical details were provided to be able to understand the results. For example, if the current authors were unable to determine whether the analysis performed was suited to the study design, or if it was unclear whether variables were recorded prior to clozapine initiation.

Data extraction and quality assessment

Data on the study population, study design and duration, clozapine response definition, clozapine dose and/or plasma levels, analysis strategy, plus any demographic and clinical variables measured prior to clozapine initiation were extracted. Where articles reported the proportion of responders over multiple time-points, the longest time point was used, to provide maximal time for response. All data were extracted by one author (KG) and independently verified by another (EM). Overall study quality was assessed using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS). Authors KG and EM independently rated each study and final ratings were a consensus (online Supplementary materials 2).

Meta-analysis

Studies were eligible for quantitative analysis if clozapine response was defined as ⩾20% reduction in positive, negative or total score on the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) or Positive and Negative Symptom Scale (PANSS) from baseline to follow-up. We chose a reduction in symptom severity as our primary outcome measure because it remains the most common criteria for treatment response since Kane's landmark study (Kane et al., Reference Kane, Honigfeld, Singer and Meltzer1988) and has greater reliability than measures of functional improvement. Percentage reduction in symptom severity from baseline may be the most appropriate measure for the treatment-resistant patient group, where absolute remission is rare (Suzuki et al., Reference Suzuki, Uchida, Watanabe and Kashima2011). Furthermore, a threshold of 20% was chosen given evidence that this improvement corresponds to a clinically significant effect in treatment-refractory patients (Leucht et al., Reference Leucht, Kane, Kissling, Hamann, Etschel and Engel2005a; Reference Leucht, Kane, Kissling, Hamann, Etschel and Engel2005b). To be included in the meta-analysis, summary statistics (mean and standard deviation) of a variable had to be reported separately by clozapine responder status in at least three articles.

Meta-analyses were performed using the Jamovi statistical software package (v1.6.4; The Jamovi Project, 2020). A random effects model was used to determine overall effect size of mean group difference between clozapine responders and non-responders, with alpha set at 0.05. A Hedges g of 0 indicates no group difference, and a positive or negative Hedges g denotes higher or lower mean values in clozapine non-responders than clozapine responders. Between study heterogeneity was quantified using the I 2 statistic where values of 0.25, 0.50 and 0.75 correspond to low, moderate and high degrees of heterogeneity (Higgins, Thompson, Deeks, & Altman, Reference Higgins, Thompson, Deeks and Altman2003). Publication bias was assessed by visual inspection of funnel plot symmetry, where an asymmetric funnel suggests the possibility of publication bias.

The primary analysis included all available studies. Secondary analysis was restricted to studies with a follow-up period of 12 weeks or longer, to align with the recommended minimum amount of time to evaluate clozapine response (Howes et al., Reference Howes, McCutcheon, Agid, de Bartolomeis, van Beveren, Birnbaum and Correll2017).

Results

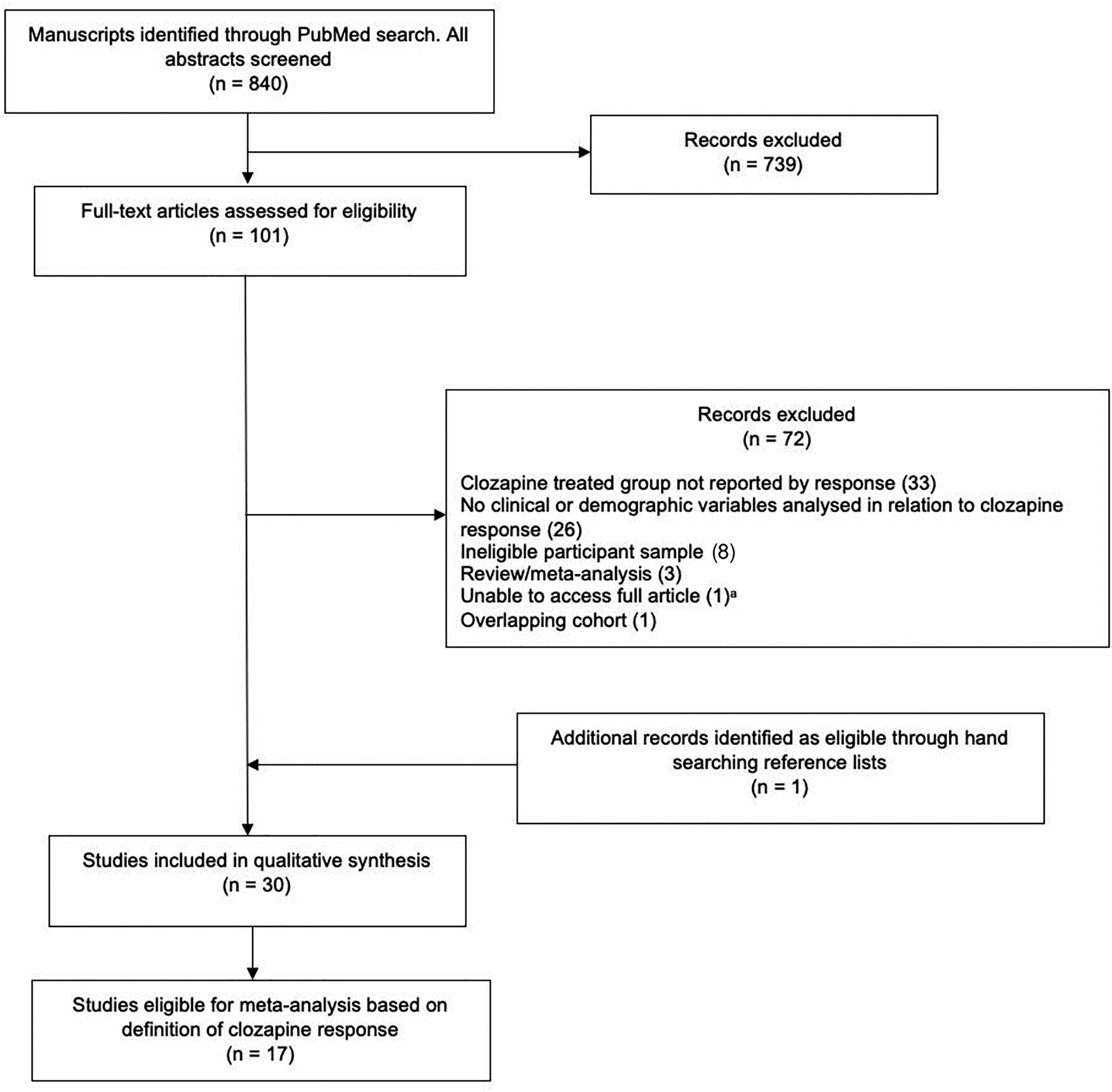

Figure 1 shows a PRISMA flowchart. The database search returned 840 articles. Abstract screening identified 101 potentially eligible articles. On review of the full-text 29 of these were eligible for systematic review, and one additional eligible article was identified via handsearching references. In total, 30 studies met systematic review inclusion criteria (online Supplementary Table S1).

Fig. 1. PRISMA flow diagram for study selection.

aOnline archive search of Annals of Clinical Psychiatry performed; full article unaccessible (Moeller et al., Reference Moeller, Chen, Steinberg, Petty, Ripper, Shah and Garver1995).

Study characteristics

Twenty-one articles were prospective studies of clozapine response. Of these, twenty were observational studies where clozapine was administered as part of routine clinical care. The other article described a randomised clinical trial of clozapine v. haloperidol, where the clinical and demographic factors associated with clozapine response were reported. Eight articles collated data from medical records to determine clozapine response retrospectively. Of these, two articles included mirror image analyses, where outcomes before and after clozapine treatment were compared within-subjects. One article reported cross-sectional data where response to clozapine was determined based on persistence and severity of current symptoms at the time of study, although response status in approximately 10% of the sample was subsidised with retrospective information on change in symptom severity from a pre-treatment period.

Study sample sizes ranged from 18 to 502 participants, and included samples across Europe, North America, Asia and Oceania. The follow-up period to assess clozapine response ranged from 5 weeks to >7 years. The range in proportion of patients failing to respond to clozapine was 28–81% (online Supplementary Table S2), which varied according to the definition of response, indication for treatment and duration of treatment trial. Twenty articles (67%) reported clozapine dosage data and clozapine plasma concentration was reported in six (20%) (online Supplementary Table S3).

Outcome measures of clozapine response

For the qualitative review there was substantial variation in outcome measures of clozapine response (Table 1), and six studies employed more than one definition.

Table 1. All study definitions of clozapine response

a Eligible for meta-analysis (see online Supplementary Table S5 for complete meta-analysis screening).

Symptom severity rating scales were the most frequently used outcome measure (n = 22), and included the BPRS (n = 12), BPRS-psychosis (n = 1) and PANSS (n = 3). One study used the Scale for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms (SAPS) and the Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS). The Clinical Global Impression (CGI) was the only scale used to assess treatment response in four studies, and a further four studies used the CGI in alongside the BPRS or PANSS. The clinical assessment scales used were not specified in one article (Üçok et al., Reference Üçok, Çikrikçili, Karabulut, Salaj, Öztürk, Tabak and Durak2015). Service use outcomes were used in seven articles and included the number and duration of psychiatric hospitalisations, time from clozapine initiation until rehospitalisation or discharge, and within-subject differences in hospital admissions before and during clozapine treatment. Functional definitions of clozapine response were used in eight studies, including improvements on the Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF), Health of the Nation Outcome Scales (HoNOS) and EQ-VAS, and employment status.

Demographic and clinical variables associated with clozapine response

Twenty baseline variables were measured (online Supplementary Table S4). Associations with clozapine treatment response were evaluated by (1) comparisons of baseline variable between responder and non-responder groups, (2) associations between baseline variables and continuous measures of response or (3) comparison of response rates between different levels of a baseline variable. Statistical tests, effect sizes, confidence intervals (CIs) and p values are reported where available in online Supplementary Table S4. The following section describes variables significantly associated with clozapine response in at least two separate studies, with the same direction of effect.

Age at clozapine initiation

Of the 21 studies testing for an effect of age, six reported an association between younger age and a better response to clozapine. Between group comparisons of clozapine responders and non-responders was assessed in three prospective studies with follow-ups ranging from 6 weeks to 12 months. All three found clozapine responders were younger than non-responders (Conley, Carpenter, & Tamminga, Reference Conley, Carpenter and Tamminga1997; Hofer et al., Reference Hofer, Hummer, Kemmler, Kurz, Kurzthaler and Fleischhacker2003; Wong et al., Reference Wong, Leung, Mak, Ng, Chan, Hon-Kee Cheung and Wai-Kiu Tsang2006). Conley et al. (Reference Conley, Carpenter and Tamminga1997) also reported age was the only variable significantly associated with percentage change in CGI improvement in a multiple linear regression model. This finding was replicated in a retrospective chart review, which found those displaying good response to clozapine were significantly younger than those with minimal or no response (Üçok et al., Reference Üçok, Çikrikçili, Karabulut, Salaj, Öztürk, Tabak and Durak2015). Gee et al. (Reference Gee, Shergill and Taylor2016) compared outcomes during pre- and post-clozapine treatment periods within subjects and found the reduction in hospital admission days was greater in younger patients when compared to the older clozapine-treated group. In another study, younger age was associated with higher likelihood of employment after 1 year of treatment (Kaneda, Jayathilak, & Meltzer, Reference Kaneda, Jayathilak and Meltzer2010).

In contrast, one study found that younger patients had higher rates of rehospitalisation after clozapine initiation compared to older patients (Kelly, Gale, & Conley, Reference Kelly, Gale and Conley2003).

Age of onset of psychosis

Of 15 studies that examined age at onset of psychosis, three found a significant association between older age of onset and a good response to clozapine. No studies reported the opposite pattern of association. When clozapine response was defined as ⩾20% improvement on BPRS and total score ⩽35 at a 16-week follow-up, one study reported an older age of onset in responders (Semiz et al., Reference Semiz, Cetin, Basoglu, Ebrinc, Uzun, Herken and Ates2007). Furthermore, older age of onset predicted better response to clozapine in a logistic regression model controlling for gender, age, weight gain, diagnosis subtype, baseline BPRS and baseline SAPS scores. The same response criteria (plus follow-up CGI score ⩽3) was applied in an earlier study looking at cumulative percentage of patients who responded to clozapine at 12, 24 and 52 weeks (Lieberman et al., Reference Lieberman, Safferman, Pollack, Szymanski, Johns, Howard and Kane1994). Here, age of onset was dichotomised to above or below 19 years. Those with an age of onset >19 years reached response status in a shorter amount of time in survival analysis. Preserving age of onset as a continuous variable, Nielsen and colleagues found that later age of onset was associated with longer time to psychiatric hospitalisation when readmission did occur (Nielsen, Nielsen & Correll, Reference Nielsen, Nielsen and Correll2012). Clozapine dose across the entire sample was dichotomised using a median split and there was a trend towards a later age of onset in the group treated with lower doses, suggesting that patients with later onset responded at lower doses.

Duration of illness

Fifteen articles tested for an effect of duration of illness. Of these, six found an association between shorter duration of illness and better outcomes. No studies reported the opposite pattern of association.

When participants were categorised as responders or non-responders using clinical outcome scales, clozapine responders had a shorter duration of illness (Wong et al., Reference Wong, Leung, Mak, Ng, Chan, Hon-Kee Cheung and Wai-Kiu Tsang2006). Üçok et al. (Reference Üçok, Çikrikçili, Karabulut, Salaj, Öztürk, Tabak and Durak2015) similarly found a shorter duration of illness for those in the good response group compared to those in the minimal or no improvement groups (13 ± 8 v. 18 ± 8.9 years). Another study reported time taken for symptoms to decrease by at least 20% was greater for those who had been unwell for a longer period, and overall odds of reaching response criteria reduced as illness duration increased (Lieberman et al., Reference Lieberman, Safferman, Pollack, Szymanski, Johns, Howard and Kane1994). Furthermore, one study reported a negative correlation between length of illness and percentage change in BPRS scores (Manschreck, Redmond, Candela, & Maher, Reference Manschreck, Redmond, Candela and Maher1999). In the same study, hospitalised non-responders also had longer duration of illness than both non-responders who had been discharged and all responders. This was interpreted by authors as a longer duration of illness being associated with the most severe form of illness overall. Köhler-Forsberg, Horsdal, Legge, MacCabe, and Gasse (Reference Köhler-Forsberg, Horsdal, Legge, MacCabe and Gasse2017) found an association between duration of illness and the probability of reaching substantial improvement on GAF in women only. Here, the chance of improvement decreased by 15% with each year of delay. Shorter duration of illness was also associated with increased likelihood of employment at 12 months in a separate study (Kaneda et al., Reference Kaneda, Jayathilak and Meltzer2010).

Delay in clozapine initiation

Three of four studies found shorter delay in clozapine initiation after fulfilment of treatment resistance criteria was associated with a more favourable response. The fourth article found no effect of length of clozapine delay on subsequent length or number of inpatient admissions (Gee et al., Reference Gee, Shergill and Taylor2016).

Shah et al. (Reference Shah, Iwata, Brown, Kim, Sanches, Takeuchi and Graff-Guerrero2020) found clozapine responders had a significantly shorter delay in clozapine initiation than non-responders, and delay in clozapine initiation was a significant predictor of clozapine response in regression analysis. Here, age at clozapine initiation was not significantly associated with clozapine response and therefore unlikely to be driving this effect. Üçok et al. (Reference Üçok, Çikrikçili, Karabulut, Salaj, Öztürk, Tabak and Durak2015) instated a logistic regression model where the dependent variable was level of improvement on clozapine treatment (good v. none or minimal). Delay in clozapine initiation was identified as the only baseline variable contributing to symptomatic improvement. Furthermore, patients in the good response group had been prescribed clozapine after a shorter delay from treatment resistance onset compared to those in the non-response group.

Similarly, Yoshimura and colleagues found that delay in clozapine initiation was the only significant predictor of symptomatic improvement on the BPRS and BPRS-psychosis in two multiple linear regression model, after controlling for age, sex, illness duration and number of previous hospitalisations (Yoshimura, Yada, So, Takaki, & Yamada, Reference Yoshimura, Yada, So, Takaki and Yamada2017) . In the same sample, receiver operation curve analysis indicated 2.8 years as the best predictive cut-off value (area under curve = 0.78, sensitivity = 0.66, specificity = 0.84). Patients with a delay in clozapine initiation longer than 2.8 years displayed significantly poorer response on the BPRS compared those with a delay in clozapine initiation less than 2.8 years.

Hospitalisations prior to clozapine initiation

Less time spent in psychiatric hospital prior to clozapine initiation was consistently associated with better response to clozapine. Of the five studies measuring length of hospitalisation prior to clozapine initiation, two found clozapine responders had spent significantly less time in hospital (Conley et al., Reference Conley, Carpenter and Tamminga1997; Köhler-Forsberg et al., Reference Köhler-Forsberg, Horsdal, Legge, MacCabe and Gasse2017), and one other reported clozapine responders had a significantly shorter length of current hospital admission (Wong et al., Reference Wong, Leung, Mak, Ng, Chan, Hon-Kee Cheung and Wai-Kiu Tsang2006). The remaining two studies reported no difference in length of current (Manschreck et al., Reference Manschreck, Redmond, Candela and Maher1999) or previous (Stern, Kahn, Davidson, Nora, & Davis, Reference Stern, Kahn, Davidson, Nora and Davis1994) hospitalisations between clozapine responders and non-responders.

Nine studies assessed the number of hospitalisations prior to clozapine treatment and four found an association between fewer pre-clozapine hospital admissions and better outcomes. Three articles reported fewer pre-clozapine hospitalisations over the total duration of illness in clozapine responders than non-responders (Nielsen et al., Reference Nielsen, Nielsen and Correll2012; Semiz et al., Reference Semiz, Cetin, Basoglu, Ebrinc, Uzun, Herken and Ates2007; Üçok et al., Reference Üçok, Çikrikçili, Karabulut, Salaj, Öztürk, Tabak and Durak2015). Nielsen et al. (Reference Nielsen, Nielsen and Correll2012) also reported the same effect when analysis was limited to hospitalisations in the year preceding clozapine treatment. The fourth article reported a greater number of hospitalisations prior to clozapine initiation was identified as a significant predictor of poor outcome in regression analysis (Shah et al., Reference Shah, Iwata, Brown, Kim, Sanches, Takeuchi and Graff-Guerrero2020).

Previous antipsychotic trials

Three of four studies found that fewer previous antipsychotic trials were associated with better clozapine response. Nielsen et al. (Reference Nielsen, Nielsen and Correll2012) reported an association between fewer pre-clozapine antipsychotic trials and lower risk of rehospitalisation although on clozapine treatment. When relapse did occur, those with fewer pre-clozapine antipsychotic trials had a longer time to readmission after clozapine initiation. This finding was replicated twice. Üçok et al. (Reference Üçok, Çikrikçili, Karabulut, Salaj, Öztürk, Tabak and Durak2015) reported patients demonstrating the best response to clozapine response had fewer adequate antipsychotic trials before clozapine compared to those with minimal or no clinical response. Shah et al. (Reference Shah, Iwata, Brown, Kim, Sanches, Takeuchi and Graff-Guerrero2020) also found clozapine responders had fewer antipsychotic trials prior to clozapine initiation than clozapine non-responders, despite the duration of non-clozapine antipsychotic treatment not differing between groups. The fourth study reported no association between the number of antipsychotics trials prior to clozapine initiation and the net change in number or length of hospital admissions after clozapine was initiated (Gee et al., Reference Gee, Shergill and Taylor2016).

Sex

Four of 23 articles reported a sex difference in clozapine response, although the direction of effect was inconsistent.

Usall, Suarez, and Haro (Reference Usall, Suarez and Haro2007) reported females were more likely to respond to clozapine treatment when response was measured using clinical symptom rating scales, but not when response was measured using scales rating overall quality of life.

In contrast, Conley et al. (Reference Conley, Carpenter and Tamminga1997) found a larger proportion of males responded to clozapine over a 12-month trial. Similarly, Nielsen et al. (Reference Nielsen, Nielsen and Correll2012) reported males were less likely to be hospitalised during clozapine treatment compared to females. When hospitalisation did occur, males were generally hospitalised after a longer time period than females, suggesting better symptom management or less frequent relapse. Szymanski et al. (Reference Szymanski, Lieberman, Pollack, Kane, Safferman, Munne and Kronig1996) calculated cumulative proportion of patients not responding to clozapine over a 12 week treatment period and found more males responded than females. Males were also less likely to withdraw from the study due to failure to improve. However, significantly more males had a paranoid diagnosis subtype, which was associated with better clozapine response in the same study.

Demographic and clinical variables not associated with clozapine response

Variables reported in two or more articles and not reproducibly associated with clozapine response were body weight, diagnosis subtype, years of education, ethnicity, relationship status, premorbid functioning, smoking, substance abuse and presence of side effects from non-clozapine antipsychotics. Workforce, level of deprivation, IQ and comorbid conditions were each measured once (online Supplementary Table S4).

Meta-analysis

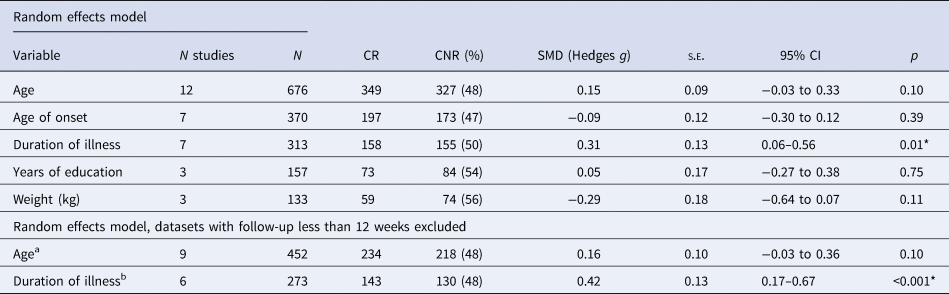

Online Supplementary Table S5 lists all articles eligible for inclusion in the meta-analysis. The variables available for meta-analysis, reported in at least three of these studies, were age, age of onset, duration of illness, years of education and body weight.

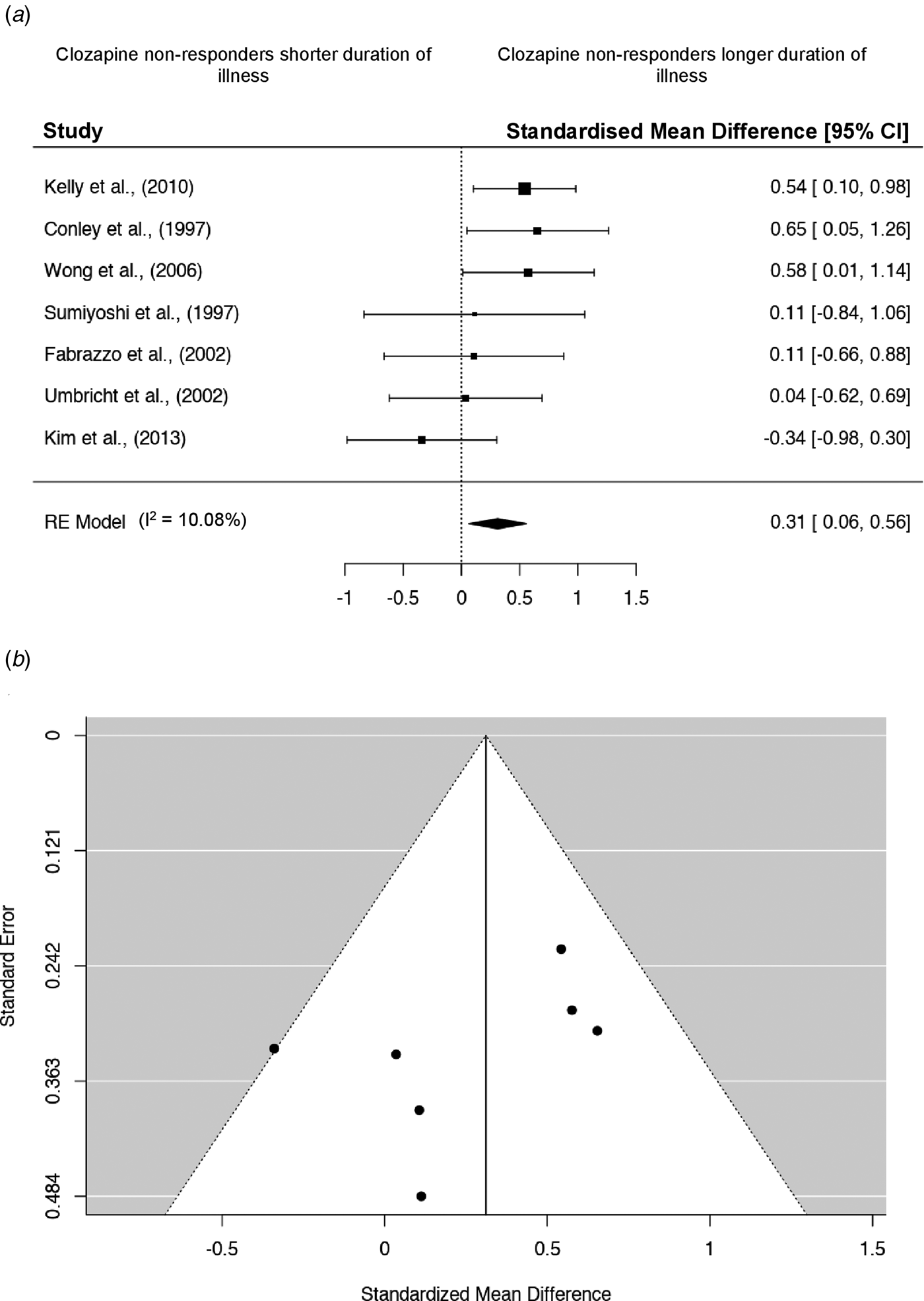

Results from all meta-analyses are detailed in Table 2. There were no significant differences in mean age, age of onset, years of education or body weight between clozapine responders and non-responders. Corresponding forest and funnel plots are presented in online Supplementary Fig. S1. In a total sample of 313 participants (50% non-responder), the mean duration of illness (years) was significantly longer in those displaying poor response to clozapine (Fig. 2a; g = 0.31; 95% CI 0.06–0.56; p = 0.01). Between study heterogeneity was moderate (Q = 8.26, I 2 = 10.08%, p = 0.23). The relative symmetry of the corresponding funnel plot suggests publication bias is unlikely, although one study does fall outside the funnel area (Fig. 2b).

Fig. 2. Meta-analysis for duration of illness. (a) Forest plot for duration of illness meta-analysis. Square sizes represent the sample size of each study. Diamonds indicate overall effect size of the meta-analysis. (b) Accompanying funnel plot for duration of illness meta-analysis.

Table 2. Meta-analyses results

N, total number of participants; CR, clozapine responders; CNR, clozapine non-responders; SMD, standardised mean difference; s.e., standard error.

*p < 0.05.

a Datasets excluded n = 3: Krivoy et al. (Reference Krivoy, Hochman, Sendt, Hollander, Vilner, Selakovic and Taler2018), follow-up = 8 weeks; Hofer et al. (Reference Hofer, Hummer, Kemmler, Kurz, Kurzthaler and Fleischhacker2003), follow-up = 6 weeks; Kim et al. (Reference Kim, Yi, Lee and Kim2013), follow-up = 8 weeks.

b Datasets excluded n = 1: Kim et al. (Reference Kim, Yi, Lee and Kim2013), follow-up = 8 weeks.

When analysis was limited to studies with a minimum follow-up period of 12 weeks, no additional significant findings were apparent (Table 2). Online Supplementary Fig. S2 displays forest and funnel plots for all sensitivity meta-analyses performed. The difference in duration of illness between responder v. non-responder groups remained significant and overall effect size increased (g = 0.42; 95% CI 0.17–0.67; p < 0.001). Between study heterogeneity was low (Q = 3.52, I 2 = 0%, p = 0.62). Visual inspection of the funnel plot suggests publication bias is unlikely, with the prior outlying study no longer included.

Discussion

Both the systematic review and meta-analysis found consistent evidence that a longer duration of illness before clozapine initiation is associated with a worse clinical response to clozapine. The systematic review also found that a poorer response to clozapine is more likely in patients who are older at clozapine initiation, have an earlier illness onset and a longer delay in clozapine initiation after the identification of treatment resistance. More previous hospitalisations and antipsychotic trials prior to treatment with clozapine were also associated with poorer response. No consistent associations with clozapine response were found for sex, ethnicity, years of education, body weight, body mass index, smoking, premorbid functioning, relationship status, substance abuse or diagnosis subtype. Together, this supports the view that initiation of clozapine earlier in illness may be beneficial (John, Ko, & Dominic, Reference John, Ko and Dominic2018).

The main finding is that a longer duration of illness is associated with poorer response to clozapine. Our meta-analysis included studies categorising patients as clozapine responders or non-responders and found that non-responders had been unwell for significantly longer, with small to moderate effect size. This finding became more marked when analysis was restricted to studies with a follow-up of at least 12 weeks. When clozapine response was evaluated more broadly and in larger cohort studies, the same association between longer illness duration and poor clozapine response was found, suggesting this is a consistent finding. No articles reported an opposite effect, although null effects were reported in some smaller studies.

The systematic review found delay in clozapine prescription, more pre-clozapine hospitalisations and more antipsychotic trials were associated with poorer outcomes, which may reflect the presence of more severe illness and a longer duration of active symptoms prior to clozapine initiation. Neurobiological integrity, social functioning and self-care are all likely affected by sustained active symptoms (Jobe & Harrow, Reference Jobe and Harrow2005; Mitelman & Buchsbaum, Reference Mitelman and Buchsbaum2007), although the precise impact of prolonged ineffective treatment on subsequent response to clozapine requires further investigation. It is also possible that factors associated with a more severe illness will delay the point at which clozapine can be safely initiated for these patients, such as concerns of poor adherence, comorbid substance abuse, a more chaotic presentation, impaired insight and poor therapeutic alliance (Acosta et al., Reference Acosta, Bosch, Sarmiento, Juanes, Caballero-Hidalgo and Mayans2009; Baier, Reference Baier2010; Farooq, Choudry, Cohen, Naeem, & Ayub, Reference Farooq, Choudry, Cohen, Naeem and Ayub2019; Hudson et al., Reference Hudson, Owen, Thrush, Han, Pyne, Thapa and Sullivan2004; Löffler, Kilian, Toumi, & Angermeyer, Reference Löffler, Kilian, Toumi and Angermeyer2003; Olfson, Marcus, Wilk, & West, Reference Olfson, Marcus, Wilk and West2006; Velligan et al., Reference Velligan, Weiden, Sajatovic, Scott, Carpenter and Ross2009).

Our review also found that older age at clozapine initiation, younger age at illness onset and longer delay in clozapine initiation after established treatment resistance were associated with worse response to clozapine. These variables are not independent from one another and longer duration of illness may be a common factor driving their associations with poor clozapine response. Older age at first clozapine prescription has been correlated with longer delays in clozapine prescription (Najim, Heath, & Singh, Reference Najim, Heath and Singh2013; Tang et al., Reference Tang, Mao, Li, Li, Chen, Jiang and Mitchell2007) and higher likelihood of relapse (Altamura, Bobo, & Meltzer, Reference Altamura, Bobo and Meltzer2007), which could account for the observed association between older age and worse therapeutic response. Significant associations between increased age of patients and delays in starting clozapine have also been reported (Üçok et al., Reference Üçok, Çikrikçili, Karabulut, Salaj, Öztürk, Tabak and Durak2015; Yoshimura et al., Reference Yoshimura, Yada, So, Takaki and Yamada2017).

Strengths and limitations

This topic was previously reviewed almost a decade ago (Suzuki et al., Reference Suzuki, Uchida, Watanabe and Kashima2011). Our updated search identified nine more recent publications and we were able to investigate some of the most frequently reported variables using meta-analysis for the first time. Study samples only included diagnoses of schizophrenia spectrum disorders, meaning patient cohorts were comparable and strengthen the clinical relevance of findings to those with treatment-resistant schizophrenia. We also included varied definitions of clozapine response to capture broad outcomes concerning patient quality of life, illness management within the community and economic burden. Although this limits study comparability, our meta-analysis adopted more stringent inclusion criteria centred on symptomatic response to clozapine.

The duration of illness prior to clozapine initiation was often long (9–25 years in the meta-analysis), which may reflect clinical practice (Üçok et al., Reference Üçok, Yağcıoğlu, Yıldız, Kaymak, Saka, Taşdelen and Şenol2019), and limits inference about the clinical and demographic predictors of clozapine response when initiated in earlier stages of illness. There was large variation in the number of patients identified as clozapine non-responders, which may be due to variation in clozapine response definition and duration of follow-up. We were unable to assess the effect of clozapine plasma concentration on outcome due to lack of data, meaning subtherapeutic clozapine dosage or poor compliance may have been incorrectly interpreted as non-response to clozapine in some cases (McCutcheon et al., Reference McCutcheon, Beck, Bloomfield, Marques, Rogdaki and Howes2015; Potkin et al., Reference Potkin, Bera, Gulasekaram, Costa, Hayes, Jin and Gerber1994). Future research should record treatment adherence and plasma concentrations to address this potential confound (Tang et al., Reference Tang, Mao, Li, Li, Chen, Jiang and Mitchell2007). Finally, restricting our search to English language articles may have introduced bias towards studies performed in western populations.

The small number of studies available for meta-analysis meant we were unable to explore sources of heterogeneity with meta-regression or statistically assess publication bias. Total number of patients in the meta-analysis of illness duration was also small, as were sample sizes within the wider reviewed literature. We identified few prospective observational studies in large cohorts, but research spanning long time periods within naturalistic settings is generally lacking. Although studies using population registry data have access to larger patient cohorts and therefore higher statistical power, missing data and retrospective recall biases are limitations to consider. It is also important to note that final study samples risk being biased towards higher functioning patients given that (1) only patients who are relatively compliant and willing to take oral medication are successfully started on clozapine, and (2) higher drop-out of non-responders due to worse functioning and symptom severity. Variables were quantitatively evaluated by defining response on the PANSS or BPRS, but not on the CGI. The PANSS and BPRS are well suited to prospective designs while the CGI may be preferable for retrospective evaluation of response (Howes et al., Reference Howes, McCutcheon, Agid, de Bartolomeis, van Beveren, Birnbaum and Correll2017). Predictors of clozapine response as assessed on the CGI could be evaluated further in future research.

Conclusions and future directions

The association between longer duration of illness and poor outcomes has substantial clinical importance given the modifiable nature of this variable. Specifically, our finding supports identifying cases of treatment resistance earlier in the illness course and initiating clozapine as soon as possible for these patients. Further research on the mechanism(s) driving the association between duration of illness and clozapine response may better our understanding of the pathophysiology of treatment-resistant schizophrenia, and lead to improved treatment strategies.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291721000246

Financial support

KG is in receipt of a Ph.D. studentship funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Biomedical Research Centre at South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust and King's College London. The views expressed are those of the author and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.

Conflict of interest

JHM has received research funding from H Lundbeck, unrelated to this study.