Introduction

Eating disorders are life-threatening and highly prevalent psychiatric disorders that have a profound impact on the well-being of sufferers and their families (Swanson, Crow, Le Grange, Swendsen, & Merikangas, Reference Swanson, Crow, Le Grange, Swendsen and Merikangas2011). These disorders are associated with several psychiatric and medical morbidities which result in impairment in psychological as well as physiological domains (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Treatment outcomes for these disorders remain uncertain, and for many patients, the illness continues to run a relapsing and unremitting course (Wonderlich, Bulik, Schmidt, Steiger, & Hoek, Reference Wonderlich, Bulik, Schmidt, Steiger and Hoek2020).

Treatment outcome data for adolescents across the spectrum of eating disorder diagnoses remain modest. Notwithstanding, some promising treatment modalities for this patient population have emerged. Family-based treatment (FBT) has been evaluated in several randomized clinical trials (RCTs) for anorexia nervosa (AN) (c.f., Le Grange et al., Reference Le Grange, Hughes, Court, Yeo, Crosby and Sawyer2016; Lock et al., Reference Lock, Le Grange, Agras, Moye, Bryson and Jo2010; Madden et al., Reference Madden, Miskovic-Wheatley, Wallis, Kohn, Lock, Le Grange and Touyz2015), as well as for bulimia nervosa (BN) (Le Grange, Crosby, Rathouz, & Leventhal, Reference Le Grange, Crosby, Rathouz and Leventhal2007; Le Grange, Lock, Agras, Bryson, & Jo, Reference Le Grange, Lock, Agras, Bryson and Jo2015). These RCTs have demonstrated that FBT is an efficacious intervention for this patient population, and could be considered the current first-line approach for those patients who are medically fit for outpatient management (Lock & Le Grange, Reference Lock and Le Grange2019). That said, recent cohort studies (Dalle Grave, Calugi, Doll, & Fairburn, Reference Dalle Grave, Calugi, Doll and Fairburn2013; Dalle Grave, Calugi, Sartirana, & Fairburn, Reference Dalle Grave, Calugi, Sartirana and Fairburn2015; Dalle Grave, Sartirana, & Calugi, Reference Dalle Grave, Sartirana and Calugi2019b) have demonstrated that a version of enhanced cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT-E), adapted for adolescents with an eating disorder, is a promising transdiagnostic intervention for this patient population. Also relatively unexplored are potential moderators of treatment outcome for adolescents with eating disorders (c.f. Le Grange et al., Reference Le Grange, Lock, Agras, Moye, Bryson, Jo and Kraemer2012, Reference Le Grange, Lock, Agras, Bryson and Jo2015, Reference Le Grange, Hughes, Court, Yeo, Crosby and Sawyer2016; Lock, Agras, Bryson, & Kraemer, Reference Lock, Agras, Bryson and Kraemer2005; Madden et al., Reference Madden, Miskovic-Wheatley, Wallis, Kohn, Lock, Le Grange and Touyz2015). While findings from such studies are hypothesis generating at this time, they do suggest that eating-related obsessionality and eating disorder-specific psychopathology are likely candidates as moderators of treatment outcome.

The efficacy of CBT-E for adult eating disorders is well established (Byrne et al., Reference Byrne, Wade, Hay, Touyz, Fairburn, Treasure and Crosby2017; Poulsen et al., Reference Poulsen, Lunn, Daniel, Folke, Mathiesen, Katznelson and Fairburn2014), and as described above, has been adapted for an adolescent patient population (Dalle Grave & Calugi, Reference Dalle Grave and Calugi2020) with promising outcomes (Dalle Grave et al., Reference Dalle Grave, Calugi, Doll and Fairburn2013). An obvious next step, and the primary goal of the present study, was to compare the relative effectiveness of FBT and CBT-E on measures of weight and eating disorder symptomatology among adolescents presenting with a DSM-5 eating disorder diagnosis [excluding Avoidant/ Restrictive Food Intake Disorder (ARFID)]. A secondary goal was to conduct an exploratory moderator analysis to investigate which of these two treatments might be more optimal for different patient groups. In this effectiveness design, families were given a choice between FBT and CBT-E. Therefore, a tertiary goal was to learn whether this choice might result in differences between treatment groups along key clinical parameters.

Method

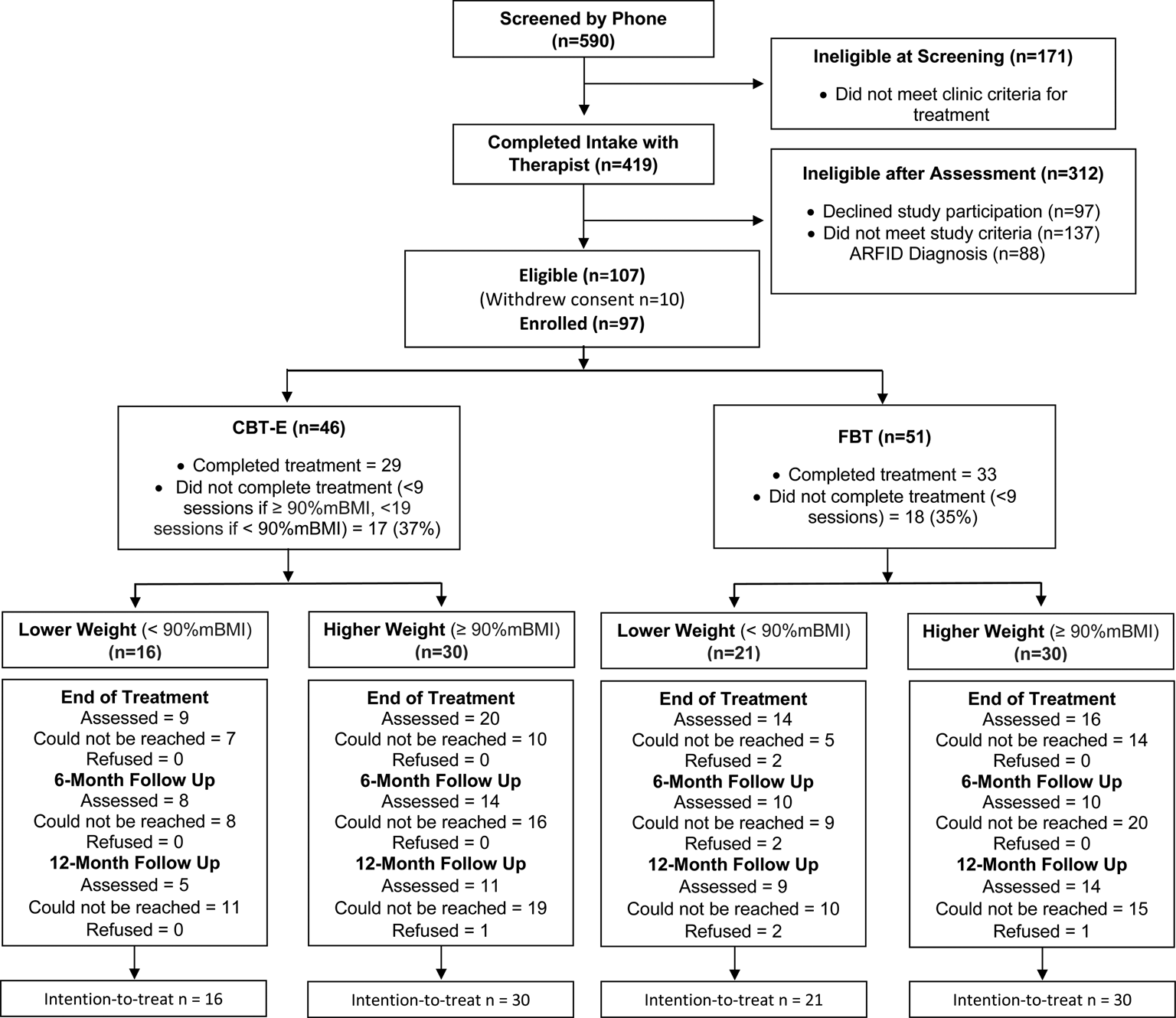

The Center for the Treatment of Eating Disorders (CTED) at Children's Minnesota, MN, a pediatric specialty clinic in the USA, provides inpatient and outpatient treatment to youth and their families. This program provides care to an average number of about 400 patients per year for medical stabilization and/or outpatient management. Over the course of the study period (July 2015–November 2019), 419 patients completed an intake assessment. Of these, 312 were ineligible; 97 declined to participate in research, 137 did not meet study criteria (i.e. prior FBT/CBT-E; did not commit to treatment; >19 years; no eating disorder diagnosis; no interpreter in native language; substance dependency; co-existing medical diagnosis), and 88 met criteria for ARFID. Consequently, 107 patients met the eligibility criteria for the study. Of those, 10 families withdrew consent, and 97 patients (83%) and their families were enrolled and offered a choice between one of two manualized treatments: FBT (Le Grange & Lock, Reference Le Grange and Lock2007; Lock & Le Grange, Reference Lock and Le Grange2012) or CBT-E (Dalle Grave & Calugi, Reference Dalle Grave and Calugi2020). Fifty-one (52.5%) participants/families chose FBT, and 46 (47.5%) chose CBT-E (see Fig. 1). Because the content and duration of CBT-E differ based on the adolescent's initial weight, the sample was divided into a lower weight cohort [<90% median body mass index (mBMI); 38% of participants), and a higher weight cohort (⩾90%mBMI; 62% of participants).

Fig. 1. Consolidated standards of reporting trials (CONSORT) diagram. Note: FBT, family-based treatment; CBT-E, enhanced cognitive-behavior therapy.

Participants

All patients were approached by a research assistant, who explained treatment and research procedures. At intake, and prior to the start of treatment, consent (parents and participants ⩾18 years of age) and assent (participants ⩽17 years of age) were obtained. Participants included youth aged 12–19 years old, living with their families/guardian, planning to engage in outpatient treatment at CTED for a DSM-5 diagnosed eating disorder (excluding ARFID), and medically stable for outpatient treatment. Participants were excluded when diagnosed with a co-morbid medical disorder known to influence eating or weight (i.e. pregnancy, cancer); psychotic disorder; acute suicidality; or substance abuse and/or substance dependence.

Assessments and procedures

Intake consists of a comprehensive multi-disciplinary assessment, and involves the following meetings: (1) medical assistant to assess vital sign stability, reviewed by a psychiatrist (Society of Adolescent Medicine guidelines; Golden et al., Reference Golden, Katzman, Sawyer, Ornstein, Rome, Garber and Kreipe2015); (2) research staff/CTED clinician for semi-structured diagnostic interviews (Eating Disorder Examination (EDE) (Fairburn, Cooper, & O'Connor, Reference Fairburn, Cooper, O'Connor and Fairburn2008), and a battery of questionnaires; (3) diagnostic assessment with a clinician; and (4) consultation with a psychiatrist to review care plan. Patients, whose first contact with CTED was in the inpatient medical setting, completed the diagnostic interviews and battery of questionnaires before discharge to outpatient care. Given that hospital stays were quite brief (M = 13.1 days, s.d. = 10), assessments were not repeated upon starting outpatient treatment. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Children's Minnesota, MN.

Measures and semi-structured diagnostic interviews

Primary outcomes were; (1) rate of weight gain (%mBMI) and (2) eating disorder psychopathology [EDE or EDE-Questionnaire (EDE-Q) (Fairburn & Beglin, Reference Fairburn and Beglin1994)] from baseline to end-of-treatment (EOT) [The EDE-Q was utilized when the EDE was not available given the high concordance rates between these two measures (c.f. Berg et al., Reference Berg, Stiles-Shields, Swanson, Peterson, Lebow and Le Grange2012)]. Semi-structured interviews as well as paper-and-pencil measures were completed with adolescents and parents at baseline, EOT, and at 6 and 12 months posttreatment. No remuneration for completion of assessments was available to participants.

Secondary outcomes were the Clinical Impairment Assessment (CIA) (Bohn & Fairburn, Reference Bohn, Fairburn and Fairburn2008), Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI) (Beck & Steer, Reference Beck and Steer1993), Child Depression Inventory (CDI-2) (Kovacs, Reference Kovacs2010), and the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (RSE) (Rosenberg, Reference Rosenberg1965). Parents completed the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) (Achenbach & Edelbrock, Reference Achenbach and Edelbrock1983), the Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI) (Derogatis & Spencer, Reference Derogatis and Spencer1993), and the McMaster Family Assessment Device (FAD) (Epstein, Baldwin, & Bishop, Reference Epstein, Baldwin and Bishop1983). The Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview for Children and Adolescents (MINI-Kid) (Sheehan et al., Reference Sheehan, Sheehan, Shytle, Janavs, Bannon, Rogeres and Wilkinson2010) was used to assess co-occurring psychiatric diagnoses, and was conducted at baseline only. At weeks 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, and 12 of treatment, patients rated the suitability of their treatment, and how successful they thought the therapy would be, on a 10-point Likert scale.

Treatments

In this non-randomized effectiveness study, patients and their parents were given a choice between FBT (Le Grange & Lock, Reference Le Grange and Lock2007; Lock & Le Grange, Reference Lock and Le Grange2012) or CBT-E (Dalle Grave & Calugi, Reference Dalle Grave and Calugi2020; Fairburn, Reference Fairburn2008). At the initial assessment, families were provided two one-page information sheets, one for FBT and one for CBT-E, which described each treatment in terms of patient and family expectations should they select one treatment as opposed to the other (see Supplemental Materials, and for a description of the conceptual distinctions between FBT and CBT-E, see Dalle Grave, et al. (Reference Dalle Grave, Eckhardt, Calugi and Le Grange2019a)). All treating clinicians (doctoral-level psychologists and masters-level clinical social workers) received in-person training in FBT and CBT-E before the start of the study, and followed by monthly supervision for the duration of the study. Training and supervision were delivered by expert developers of these treatments.

Family-Based Treatment (Le Grange & Lock, Reference Le Grange and Lock2007; Lock & Le Grange, Reference Lock and Le Grange2012). FBT for adolescent eating disorders usually includes all members of the adolescent's immediate family. Treatment progresses through three phases, with the first (~10 sessions) focusing mainly on guiding the parents to support their adolescent toward weight restoration (when appropriate), and disrupting eating disorder behaviors (e.g. binge eating and purging). The second phase (~5–7 sessions) focuses on assisting the parents to restore food choices to the adolescent, with an emphasis on the developmental stage of the adolescent. Phase 3 is brief (2–3 sessions), focusing on adolescent developmental matters and helping the parents and their offspring navigate these tasks largely in the absence of acute eating disorder symptoms. Twenty treatment sessions are provided over a span of approximately 6 months.

Enhanced Cognitive-Behavior Therapy (Dalle Grave & Calugi, Reference Dalle Grave and Calugi2020; Fairburn, Reference Fairburn2008). CBT-E is designed to address the core psychopathology of all eating disorders. CBT-E posits the eating problem as belonging to the individual, and is designed to encourage the adolescent, rather than their parent, to take control of the problem. Parents are not excluded from participating in treatment, but their involvement is limited to helping create a family environment that allows for recovery (c.f., Dalle Grave et al., Reference Dalle Grave, Eckhardt, Calugi and Le Grange2019a). Patients are actively involved in all phases of treatment, including the decision to address weight regain and/or binge eating and purging, with the goal of promoting self-management. CBT-E is a collaborative approach, and patients are encouraged to be active in making changes. A primary goal of CBT-E is to address the patient's eating disorder psychopathology, i.e. patients' concerns about shape, weight, dietary restraint and restriction, and other extreme weight control behaviors. Following manualized CBT-E guidelines, for patients in the lower weight cohort, treatment involves 40 sessions over 9–12 months. For those in the higher weight cohort, treatment involves 20 sessions over the course of 6 months.

Participant safety and hospitalization criteria

Participants were followed by their primary care physician/CTED psychiatrist to ensure medical stability throughout the study. If unstable, or presenting with an acute psychiatric risk, participants were admitted to the inpatient unit at Children's Minnesota, MN, but were not dropped from the study as a result of such required inpatient care.

Statistical analysis

No a priori power analysis was conducted as our goal for this effectiveness study was to enroll the maximum number of eligible patients given our timeframe. Based upon the differing length of treatment in manualized CBT-E, which is based upon baseline weight status, all analyses were stratified by weight at beginning of treatment. This resulted in a lower weight cohort, which included patients <90%mBMI, and a higher weight cohort, which included patients ⩾90%mBMI. FBT and CBT-E were compared at baseline on demographic and clinical characteristics using χ2 or Fisher's exact tests for categorical data and independent t tests or Mann–Whitney U non-parametric tests for continuous measures.

Mixed-effects linear models were used to compare the trajectory of %mBMI between FBT and CBT-E across treatment visits and follow-up assessments. Analyses were based upon all available data and missing data were not imputed. Models included random intercepts, and fixed effects for treatment group, study visitFootnote 1, and treatment group-by-study visit interactions. Fixed effects for quadratic (study visit) and cubic (study visit) components were added to allow non-linear trajectories. Model estimation was based upon full information maximum likelihood. Given the non-randomized nature of the design, baseline measurements were included as data points in the model rather than as covariates. This allowed for a comparison between treatment groups at baseline. Moderators of treatment were tested by adding main effects for moderator, as well as interactions for moderator-by-study visit, moderator-by-treatment group, and moderator-by-study visit-by-treatment group. Sensitivity analyses were conducted adjusting the analyses for propensity score, which represented the predicted probability of choosing FBT using all available baseline demographic and clinical assessments. Logistic regression analyses were conducted using all available baseline and demographic characteristics to predict the treatment selected (CBT-E or FBT). The predicted probability of selecting CBT-E for each participant, referred to as a propensity score, was derived from this model. Sensitivity analyses were conducted for all primary and secondary outcomes using propensity score as a covariate in the model.

Mixed-effects repeated-measures models were used to compare treatment groups on EDE/EDE-Q scores and secondary outcome measures at baseline, EOT, 6- and 12-month follow-up. Again, models were based upon available data and missing data were not imputed. Models included a random intercept, and fixed effects for treatment group, study visit, and treatment group-by-study visit interactions. Post hoc contrasts were used to compare treatment groups at each study visit.

Results

Study participants

Participants (N = 97) presented with an average age of 14.6 years (s.d. = 1.8, range = 11–19), mean duration of illness of 17.0 months (s.d. = 18.3, range = 1–84), and were mostly female (80 of 97; 82.5%). The mean percent mBMI for the lower weight cohort (N = 37) was 83.6 (s.d. = 4.1, median = 83.4, range = 74.8–89.8), and 103.7 (s.d. = 11.9, median = 101.21, range = 90.3–142.1) for the higher weight cohort. The majority of participants met DSM-5 criteria for AN or AAN (76 of 97; 78%), for the lower weight cohort, 92% met criteria for AN [the remainder met criteria for atypical AN (AAN) or UFED], and for the higher weight cohort, 67% met criteria for ANFootnote 2 (n = 12) or AAN (n = 28), 20% BN, purging disorder or BED, and 13% UFED (the majority presenting with body image concerns, but without significant weight loss to meet the criteria for AAN). Weight gain was a primary treatment goal for the majority of this study sample (84 of 97; 87%). Most participants identified as Caucasian [86 of 97; 89% (Hispanic = 9)], and the remainder as African American (1 of 97; 1%), Asian (3 of 97; 3.1%), Multiracial/Other (4 of 97; 4.1%), and Not reported (3 of 97; 3.1%), and most participants lived with their family of origin (67 of 97; 69.1%). More than two-thirds had a history of prior mental health treatment and/or psychiatric hospitalization (67 of 97; 69.1%). Table 1 presents baseline demographic and clinical characteristics dividing the sample into the two weight cohorts by treatment modality. Regardless of weight cohort, participants who elected CBT-E were older, had been ill longer, presented with higher depression and anxiety, more prior mental health treatment, and higher rates of psychosocial impairment due to eating disorder features (all ps 0.034–0.0001).

Table 1. Participant characteristics FBT v. CBT-E by weight status

BAI, Beck Anxiety Inventory; CIA, Clinical Impairment Assessment; CDI-2, Child Depression Inventory; CBCL, Child Behavior Checklist; FAD, Family Assessment Device.

a Percent Caucasian (Hispanic + non-Hispanic).

b DSM-5 AN or AAN = 76; BN, BED or Purging Disorder = 12; UFED = 9.

c χ2 value not calculable (zero cases).

Bold p-values = statistical significance.

Treatment completion

Among the lower weight FBT cohort, five (23.8%) participants completed <50% of treatment sessions, seven (33.3%) completed 50–75% of sessions, and nine (42.9%) completed >75% of sessions. Among the lower weight CBT-E cohort, five (31.3%) participants completed <50% of treatment sessions, five (31.3%) completed 50–75% of sessions, and six (37.5%) completed >75% of sessions (χ2 = 0.26, df = 2, p = 0.877). In the higher weight FBT cohort, 15 (50.0%) participants completed <50% of treatment sessions, three (10.0%) completed 50–75% of sessions, and 12 (40.0%) completed >75% of sessions. Among the higher weight CBT-E cohort, two (6.7%) completed <50% of treatment sessions, six (20.0%) completed 50–75% sessions, and 22 (73.3%) completed >75% of sessions (χ2 = 13.88, df = 2, p = 0.001).

Primary and secondary treatment outcomes

Primary and secondary outcomes at each time point across the two treatment groups were initially conducted without adjustment. Results of sensitivity analyses using propensity adjustment produced comparable results to unadjusted models. Consequently, we only present the unadjusted results here.

Figure 2 presents the primary outcome of weight gain in the lower weight and higher weight cohorts. There were no differences between FBT and CBT-E in weight (%mBMI) at the beginning of treatment in either the lower weight cohort (est. = −2.361, s.e. = 1.854, p = 0.207) or the higher weight cohort (est. = −2.283, s.e. = 2.994, p = 0.449). However, the slope of weight gain at EOT was significantly higher for FBT than for CBT-E in the lower weight cohort (est. = 0.597, s.e. = 0.096, p < 0.001) and the higher weight cohort (est. = 0.495, s.e. = 0.83, p < 0.001) (Fig. 2). Table 2 presents the average %mBMI by weight cohort at baseline, end of treatment and 6- and 12-month follow-up. There were no differences in weight gain between treatment groups, across weight cohorts, at the 6- or 12-month follow-up time points (Fig. 3a and 3b). There were no significant differences between FBT and CBT-E at EOT and at follow-up on eating disorder symptomatology (EDE/Q Global Score) in either weight cohort.

Fig. 2. Slope of weight gain (percent mBMI) for FBT v. CBT-E at EOT.

Fig. 3. Slope of weight (% mBMI) for FBT v. CBT-E baseline to follow-up.

Table 2. Secondary outcomes: baseline through 12-month follow-up (M/s.d.)

EDE/Q-G, Eating Disorder Examination (or Questionnaire) Global Score; BAI, Beck Anxiety Inventory; CIA, Clinical Impairment Assessment; CDI-2, Child Depression Inventory; BSI, Brief Symptom Inventory; RSE, Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale; FAD, Family Assessment Device; CBCLT, Child Behavior Checklist Total Score.

Key: Primary outcome = slope of weight gain (%mBMI) and main effect for treatment (EDE/Q) at EOT; ME = main effect; ME refers to comparison between FBT and CBT-E at each time point, i.e.: aBaseline (B) comparison of %mBMI between treatments, separately by weight cohort; bEOT comparison; c12-month follow-up (12 m) comparison; d6-month follow-up (6 m) comparison.

Int = interaction effect, that is, treatment by visit interaction; and NS = no significant ME or interaction; superscript refers to ME at time point, e.g. baseline, EOT, etc.

Bold p-values = statistical significance.

As for secondary outcomes (Table 2), there were significant differences between FBT and CBT-E at all time points, favoring FBT. However, these were likely due to significant baseline differences between treatment groups in variables of interest. The only exceptions were for the higher weight cohort where CBCL (internalizing) was significantly lower for FBT than CBT-E at EOT (50.1 v. 58.7; est. = −8.73, s.e. = 3.66, p = 0.019), and at 12-month follow-up (49.6 v. 61.3; est. = 12.00, s.e. = 4.42, p = 0.008), and CBCL-T was significantly lower for FBT than CBT-E at 12-month follow-up (43.7 v. 53.4; est. = −9.22, s.e. = 4.42, p = 0.040).

Treatment effect moderators of primary outcome

Four baseline variables emerged as potential treatment effect moderators of weight gain at EOT for the lower weight cohort only; CDI-2 (est. = 0.008, s.e. = 0.003, p = 0.020), age (est. = −0.072, s.e. = 0.023, p = 0.002), prior hospitalization for a co-existing psychiatric disorder (est. = −0.187, s.e. = 0.093, p = 0.048), and family status (family of origin/reconstituted familyFootnote 3) (est. = −0.247, s.e. = 0.089, p = 0.007). Weight gain for FBT patients was faster than for those in CBT-E, with comparable rates of weight gain in FBT regardless of depression level, but significantly poorer weight gain for those in CBT-E with higher levels of depression. Patients gained weight faster in FBT than CBT-E regardless of age, but patients in FBT who were younger had better weight gain than those who were older, whereas patients in CBT-E who were older had better weight gain than those who were younger. Patients without a history of psychiatric hospitalization gained weight in FBT and CBT-E, whereas a positive history of prior psychiatric hospitalization was associated with weight gain in FBT, but weight loss in CBT-E. For both treatments, patients living within their family of origin had less weight gain than those living in reconstituted families, but the difference was more pronounced in CBT-E (poorer weight gain if living in family of origin) (Fig. 4). No variables emerged as significant treatment effect moderators of EDE/Q at EOT or follow-up.

Fig. 4. Potential treatment effect moderators at end-of-treatment for the lower weight cohort.

Non-specific predictors of primary outcome

Non-specific predictors of weight gain in the lower weight cohort included CBCL externalizing (est. = −0.009, s.e. = 0.004, p = 0.025), a co-occurring DSM psychiatric disorder (est. = 0.128, s.e. = 0.043, p = 0.004), a history of abuse (est. = −0.184, s.e. = 0.049, p < 0.001), and a history of previous mental health treatment (est. = 0.159, s.e. = 0.049, p = 0.001). A higher rate of weight gain was achieved for those with lesser externalizing problems, no co-occurring psychiatric disorder, no prior mental health treatment, and no history of abuse. History of abuse was also a non-specific predictor of outcome in the higher weight cohort (est. = −0.082, s.e. = 0.038, p = 0.032), such that rate of weight gain was poorer for those with a history of abuse. No variables emerged as significant non-specific predictors of EDE/Q at EOT or follow-up.

Hospitalization during treatment phase

The percentage of patients who were hospitalized during treatment in the full sample was 9.8% (5 of 51) in FBT, and 21.7% (10 of 46) in CBT-E (Fisher's exact p = 0.159). In the lower weight cohort, the percentage of patients hospitalized during treatment was 19.0% (4 of 21) in FBT, and 43.8% (7 of 16) in CBT-E (Fisher's exact p = 0.151), and in the higher weight cohort was 3.3% (1 of 30) in FBT and 10.0% (3 of 30) in CBT-E (Fisher's exact p = 0.612).

Mental health treatment during follow-up

The percentage of patients receiving any mental health intervention post-treatment was 9.8% (5 of 51) in FBT and 6.5% (3 of 46) in CBT-E (Fisher's exact p = 0.718) for the full sample. In the lower weight cohort, the percentage was 19.0% (4 of 21) for FBT, and 18.8% (3 of 16) in CBT-E (Fisher's exact p = 1.00), and in the higher weight cohort, the percentage was 3.3% (1 of 30) for FBT, and 0% (0 of 30) for CBT-E (Fisher's exact p < 1.00).

Treatment suitability and patient expectancy

Overall, mean suitability ratings for FBT were 7.42 (s.d. = 3.10), and 8.38 for CBT-E (s.d. = 2.66). No significant differences between treatments in suitability ratings were found in the overall sample or separately by weight cohort (all ps ⩾0.103). Overall, mean success ratings for FBT were 7.89 (s.d. = 3.32), and 8.21 for CBT-E (s.d. = 2.11). No significant differences between treatments were found in the overall sample or separately by weight cohort (all ps ⩾0.335).

Discussion

This non-randomized study set out to compare the relative effectiveness of FBT and CBT-E for adolescents with a DSM-5 eating disorder (80% with a restrictive disorder) in terms of change in weight and eating disorder psychopathology at the end of treatment. Treatment groups were divided into two baseline weight cohorts; lower v. higher weight. Patients who chose CBT-E over FBT were older, more depressed, had been ill for longer, reported greater clinical impairment, and a greater portion had a history of prior mental health treatment. For those in the higher weight cohort, patients whose families chose CBT-E had higher anxiety, were more likely to have a co-occurring psychiatric disorder, as well as a history of prior psychiatric hospitalization. For those in the lower weight cohort, families of the most underweight patients were more likely to have chosen FBT.

Regardless of weight cohort, FBT was more efficient than CBT-E in terms of the slope of weight gain from baseline to the EOT. However, this was no longer the case at either the 6- or 12-month follow-up. Initial more gradual weight gains achieved by CBT-E compared to FBT at EOT may be partly due to distinct strategies used to achieve weight gain across these two treatments. In CBT-E, weight gain (when indicated) is addressed after 4 weeks of treatment, and only when patients reach the conclusion that they need to attend to their low weight (Dalle Grave & Calugi, Reference Dalle Grave and Calugi2020). In contrast, weight gain in FBT (when indicated) is addressed at the outset, and weight goals are arguably higher than in CBT-E, while parents are supported to drive this agenda (Lock & Le Grange, Reference Lock and Le Grange2012). That said, for a substantial minority of patients in the higher weight cohort (~22%), weight gain was not a treatment goal. Therefore, relative effectiveness was defined in terms of weight gain and/or improvement in eating disorders psychopathology. In this domain, both treatments demonstrated improvements in the EDE/Q Global Score with no significant differences across time.

In terms of the secondary outcomes (controlling for baseline differences), the two treatments largely established similar gains across measures of general psychopathology and clinical impairment. That said, and for the higher weight cohort only, parents in FBT compared to CBT-E noted fewer emotional and behavioural problems in their offspring, as reported via the CBCL, at EOT and 12-month follow-up, suggesting an advantage for FBT over CBT-E in this domain. However, this finding should be tempered given the noted differences in baseline profile in that older and more unwell patients' parents opted for CBT-E rather than FBT. Albeit speculatively, it seems that parents considered an individual therapy rather than a family-based one to be more appropriate when their offspring was older and more unwell.

For the lower weight cohort only, four baseline variables were identified as potential moderators of treatment outcome at EOT, i.e., depression, age, prior psychiatric hospitalization, and family status. While tentative, it would seem appropriate to recommend CBT-E rather than FBT for lower weight patients who present with either lower levels of depression, are older, not living in their family of origin, or have no previous psychiatric hospitalizations. A similar number of baseline variables were identified as non-specific predictors; CBCL, comorbid psychiatric diagnosis, a history of abuse, and a history of prior mental health treatment. That is, for the lower weight cohort, and regardless of treatment modality, higher rates of weight gain were achieved for those with a lower CBCL (internalization), and an absence of a comorbid psychiatric history, abuse, or prior mental health treatment. For the higher weight cohort, the absence of a history of abuse predicted higher rates of weight gain, irrespective of whether the participants received FBT or CBT-E. While this study allowed for only explorative moderator analyses, it nevertheless adds to our limited capacity to better match patients with one treatment rather than another (c.f. Le Grange et al., Reference Le Grange, Lock, Agras, Moye, Bryson, Jo and Kraemer2012, Reference Le Grange, Hughes, Court, Yeo, Crosby and Sawyer2016; Madden et al., Reference Madden, Miskovic-Wheatley, Wallis, Kohn, Lock, Le Grange and Touyz2015).

With a broader lens, and consistent with recent RCTs setting a similar albeit low bar for treatment completion (Eisler et al., Reference Eisler, Simic, Hodsoll, Asen, Berelowitz, Connan and Landau2016; Le Grange et al., Reference Le Grange, Hughes, Court, Yeo, Crosby and Sawyer2016), 28% of participants did not complete 50% or more of the prescribed dose. Of note, and for the higher weight cohort only, the majority of participants in CBT-E (93%) met this threshold, whereas half of those in FBT failed to do so. Keeping in mind that patients in this cohort were, on average, older than those in the lower weight cohort, prompts the question whether an individual treatment (CBT-E) is perceived as a better fit than one in which parents take a firm lead (FBT). While our treatment completion data seem to support this hypothesis, it is not borne out by our treatment suitability and patient expectancy findings which showed no difference between CBT-E and FBT.

Largely in keeping with rates in recent RCTs (Agras et al., Reference Agras, Lock, Brandt, Bryson, Dodge, Halmi and Woodside2014; Le Grange et al., Reference Le Grange, Hughes, Court, Yeo, Crosby and Sawyer2016; Lock et al., Reference Lock, Le Grange, Agras, Moye, Bryson and Jo2010), there were no differences across weight cohort and treatment modality in terms of hospitalization during treatment (15%); seeking mental health treatment during the follow-up period (10%); or participant report of perceived expectations and suitability of treatment. Taken together, these findings seem to indicate that, outside of initial weight gain, FBT and CBT-E are on par in terms of most desired clinical outcomes.

Some limitations to this effectiveness study should be considered. First, we did not conduct an a priori power calculation to guide recruitment efforts. However, our robust findings in terms of the primary outcome measures are reassuring that we were adequately powered to detect clinically meaningful differences between treatment modalities. Second, and by design, participants were not randomly allocated to either FBT or CBT-E; instead families chose between these two treatments. While this design likely contributed to baseline differences between treatment groups, the treatment assignment method is consistent with the ‘real-world’ environment where family/patient preference is accounted for, which we were hoping to emulate in order to accurately measure treatment effectiveness. Third, compliance with post-baseline assessments was less than optimal, and although this may be due to a ‘real-world’ clinical environment as opposed to the expected rigor of an efficacy trial, our findings at follow-up should nevertheless be considered against this reality. That said, retention rates for the primary outcomes at 12-month follow-up were quite similar to the most recently published pragmatic RCT in this domain (c.f., Eisler et al., Reference Eisler, Simic, Hodsoll, Asen, Berelowitz, Connan and Landau2016). Fourth, diversity in our sample was limited and should be taken into account when considering to whom these findings might apply. Some significant strengths ought to be noted. Chief among these are expert training and regular supervision provided to clinicians, and the capacity to employ a research assistant, although not blinded, to conduct gold-standard measures through 12-month follow-up.

The current study underscores the efficiency of FBT to facilitate early weight gain among adolescents who present with a restricting eating disorder. However, in almost all other domains assessed, FBT and CBT-E achieved similar outcomes, and provide additional support for CBT-E as a viable treatment modality for adolescents with an eating disorder. The relative efficacy of FBT and CBT-E for this patient population, however, remains an empirical question that should be tested in a sufficiently powered randomized clinical design.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291720004407.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Christopher Fairburn, MD, and James Lock, MD, PhD, for their earlier support to CTED in providing therapy training prior to the onset of this study.

Financial support

We acknowledge the generous financial support from the Goven Family Foundation, who made it possible to conduct this effectiveness study.

Conflict of interest

D. Le Grange receives funding from the National Institutes of Health (USA), Children's Minnesota (USA), Royal Children's Hospital (Australia), Alberta Children's Hospital Foundation (Canada), Eating Recovery Center (USA), and royalties from Guilford Press and Routledge, and is Co-Director of the Training Institute for Child and Adolescent Eating Disorders, LLC. R. Crosby is a paid statistical consultant for Health Outcomes Solutions, Winter Park, Florida, USA. R. Dalle Grave receives royalties from Guilford Press and Springer.

Ethical standards

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and international committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.