Introduction

Distressing social interactions during childhood and adolescence are a public health problem worldwide. Across the globe, about 16% of fourth graders report being frequently harassed at their schools (Martin et al., Reference Martin, Mullis, Hooper, Yin, Foy, Palazzo, Martin, Mullis and Hooper2016). Similarly, survey data from the United States (US) suggest that around 20% of school-aged children experience different types of attacks from peers, with physical assaults peaking before age 9, and relational aggression reaching the highest points between ages 10 and 13 (Finkelhor, Turner, Shattuck, & Hamby, Reference Finkelhor, Turner, Shattuck and Hamby2015; Pontes, Ayres, Lewandowski, & Pontes, Reference Pontes, Ayres, Lewandowski and Pontes2018).

Peer victimization can include more severe forms of harassment or discrimination involving peer power imbalances (Turner, Finkelhor, Shattuck, Hamby, & Mitchell, Reference Turner, Finkelhor, Shattuck, Hamby and Mitchell2015) or intention to hurt others (Felix, Sharkey, Green, Furlong, & Tanigawa, Reference Felix, Sharkey, Green, Furlong and Tanigawa2011) as well as less severe forms of harassment (Cornell & Limber, Reference Cornell and Limber2015). Recent conceptualizations (e.g. Schacter, Reference Schacter2021; see also Card & Hodges, Reference Card and Hodges2008; and Casper, Meter, & Card, Reference Casper, Meter and Card2015) define peer victimization as being the target of direct (e.g. hitting, teasing) as well as indirect (e.g. being ignored or excluded) aggression from peers.

Peer victimization during childhood and adolescence is associated with an elevated risk of mental (Arseneault, Reference Arseneault2017) and physical (Schacter, Reference Schacter2021) health symptoms. In terms of mental health, peer victimization has been linked with increases in depression (Arseneault et al., Reference Arseneault, Milne, Taylor, Adams, Delgado, Caspi and Moffitt2008; Zwierzynska, Wolke, & Lereya, Reference Zwierzynska, Wolke and Lereya2013), anxiety (Arseneault et al., Reference Arseneault, Milne, Taylor, Adams, Delgado, Caspi and Moffitt2008; Copeland, Wolke, Angold, & Costello, Reference Copeland, Wolke, Angold and Costello2013), psychotic-like experiences (i.e. hallucinations or delusions) (Schreier et al., Reference Schreier, Wolke, Thomas, Horwood, Hollis, Gunnell and Glynn2009), and externalizing symptoms (van Geel, Vedder, & Tanilon, Reference van Geel, Vedder and Tanilon2014).

A number of plausible pathways have been proposed to explain the adverse mental health consequences of negative interpersonal relationships via a reduction in (i) social support and sense of belonging (Matthews et al., Reference Matthews, Caspi, Danese, Fisher, Moffitt and Arseneault2022); (ii) coping and emotion skills; (iii) opportunities to build resilience and develop positive social identities (van Geel, Goemans, Zwaanswijk, Gini, & Vedder, Reference van Geel, Goemans, Zwaanswijk, Gini and Vedder2018) and (iv) opportunities for engagement with other developmental goals [see Andersen, Rasmussen, Reavley, Bøggild, & Overgaard (Reference Andersen, Rasmussen, Reavley, Bøggild and Overgaard2021) for a synthesis of theories explaining how social relationships affect mental health: social support and buffering theory (Cohen & Wills, Reference Cohen and Wills1985); need to belong theory (Leary & Baumeister, Reference Leary and Baumeister1995); relational regulation theory (Lakey & Orehek, Reference Lakey and Orehek2011); thriving through relationships theory (Feeney & Collins, Reference Feeney and Collins2015); and the social cure approach (Jetten et al., Reference Jetten, Haslam, Cruwys, Greenaway, Haslam and Steffens2017)]. At the biological level, plausible mechanisms include the (v) dysregulation of the stress response system (Rudolph, Skymba, Modi, Davis, & Sze, Reference Rudolph, Skymba, Modi, Davis, Sze, van Lier and Deater-Deckard2022; Zarate-Garza et al., Reference Zarate-Garza, Biggs, Croarkin, Morath, Leffler, Cuellar-Barboza and Tye2017), (vi) epigenetic modifications (Mulder et al., Reference Mulder, Walton, Neumann, Houtepen, Felix, Bakermans-Kranenburg and Cecil2020), and (vii) changes in brain structures involved in mood and emotional regulation (Mulkey & du Plessis, Reference Mulkey and du Plessis2019; Rudolph et al., Reference Rudolph, Skymba, Modi, Davis, Yan Sze, Rosswurm and Telzer2021).

Existing studies have yielded important insights, but relatively few are based on large samples and allow for tracking longitudinal contributions of peer victimization to the development of different mental health symptoms during the transition to adolescence, as children enter the second decade of life (Sawyer, Azzopardi, Wickremarathne, & Patton, Reference Sawyer, Azzopardi, Wickremarathne and Patton2018). This transition is a critical developmental period during which some forms of peer victimization experiences seem to peak (Casper et al., Reference Casper, Meter and Card2015), compared to both younger and older age groups (Ladd, Ettekal, & Kochenderfer-Ladd, Reference Ladd, Ettekal and Kochenderfer-Ladd2017; Lebrun-Harris, Sherman, Limber, Miller, & Edgerton, Reference Lebrun-Harris, Sherman, Limber, Miller and Edgerton2019). It is also a time of major reorganization across neural, cognitive, emotional, and social systems (Dahl, Allen, Wilbrecht, & Suleiman, Reference Dahl, Allen, Wilbrecht and Suleiman2018; Dow-Edwards et al., Reference Dow-Edwards, MacMaster, Peterson, Niesink, Andersen and Braams2019; Lightfoot, Cole, & Cole, Reference Lightfoot, Cole and Cole2018; Peper & Dahl, Reference Peper and Dahl2013) marked by more independence from caregivers and increased salience of peer relationships in the onset, development, and progression of mental health symptoms (e.g. LoParo, Fonseca, Matos, & Craighead, Reference LoParo, Fonseca, Matos and Craighead2023; Rapee et al., Reference Rapee, Oar, Johnco, Forbes, Fardouly, Magson and Richardson2019). In this context, larger and more diverse samples allow researchers to explore the heterogeneity and specificity of the effects of negative social relationships on different types of mental health symptoms.

Peer victimization has costs for individuals and societies alike (Mukerjee, Reference Mukerjee2018), and interventions are relatively effective at reducing its prevalence (Fraguas et al., Reference Fraguas, Díaz-Caneja, Ayora, Durán-Cutilla, Abregú-Crespo, Ezquiaga-Bravo and Arango2021; Gaffney, Farrington, & Ttofi, Reference Gaffney, Farrington and Ttofi2019). However, it is less clear which factors buffer the negative effects on mental health once persistent aggression between peers is already occurring (Lin, Schleider, & Eaton, Reference Lin, Schleider and Eaton2021; Vannucci, Fagle, Simpson, & Ohannessian, Reference Vannucci, Fagle, Simpson and Ohannessian2021). Given that development does not occur in a vacuum and is influenced by the contexts in which it occurs (Hong & Espelage, Reference Hong and Espelage2012; Merrin, Espelage, & Hong, Reference Merrin, Espelage and Hong2018), researchers have directed their attention at social contexts with parental warmth and supportive school climate as key buffer candidates against the negative mental health consequences of peer victimization. Studies focused on the moderating role of different sources of social support typically draw from theories such as the stress-buffering (Cohen & Wills, Reference Cohen and Wills1985; Guo, Li, Wang, Ma, & Ma, Reference Guo, Li, Wang, Ma and Ma2020) and youth resilience (Kochel, Bagwell, Ladd, & Rudolph, Reference Kochel, Bagwell, Ladd and Rudolph2017; Masten, Lucke, Nelson, & Stallworthy, Reference Masten, Lucke, Nelson and Stallworthy2021) models which posit that the perception of a strong support network can attenuate the adverse psychological effects of negative life events, strengthen internal resources to cope with adversity, give a sense of group belonging and intimacy, support positive affect, feelings of self-worth, self-efficacy, being valued, cared for and understood, and provide resources to develop skills for conflict resolution and adaptive problem-solving.

There is supporting evidence for the role of parental support broadly as a protective factor (Noret, Hunter, & Rasmussen, Reference Noret, Hunter and Rasmussen2020), as parents can provide children with emotional and material resources to cope with stress and potentially attenuate the harmful effects of negative life experiences (Guo et al., Reference Guo, Li, Wang, Ma and Ma2020). Overall, the empirical evidence to date has not shown a consistent buffering effect in the face of peer victimization, with some studies showing a protective role in contexts of high-quality parent–child relationships (Rudolph, Monti, Modi, Sze, & Troop-Gordon, Reference Rudolph, Monti, Modi, Sze and Troop-Gordon2020) or frequent family communication (Elgar et al., Reference Elgar, Napoletano, Saul, Dirks, Craig, Poteat and Koenig2014), but not playing a moderating role in other settings (Demidenko et al., Reference Demidenko, Ip, Kelly, Constante, Goetschius and Keating2021; Guo et al., Reference Guo, Li, Wang, Ma and Ma2020; Hong & Min, Reference Hong and Min2018; Jiang et al., Reference Jiang, You, Hou, Du, Lin, Zheng and Ma2016; Noret et al., Reference Noret, Hunter and Rasmussen2020; Papafratzeskakou, Kim, Longo, & Riser, Reference Papafratzeskakou, Kim, Longo and Riser2011). The focus of this study is on parental warmth as a key dimension of parents' emotional support, given a long line of evidence that has shown it can buffer the link between adversity and physical health outcomes (Chen, Miller, Kobor, & Cole, Reference Chen, Miller, Kobor and Cole2011; Miller et al., Reference Miller, Lachman, Chen, Gruenewald, Karlamangla and Seeman2011).

Positive school environments have also been suggested as a protective factor. Negative peer relationships are less likely in such contexts in the first place (Guo et al., Reference Guo, Li, Wang, Ma and Ma2020; Rakesh, Seguin, Zalesky, Cropley, & Whittle, Reference Rakesh, Seguin, Zalesky, Cropley and Whittle2021), and positive school environments have also emerged as a buffer against negative mental health consequences once peer victimization has occurred (Wang, La Salle, Wu, Do, & Sullivan, Reference Wang, La Salle, Wu, Do and Sullivan2018). Yet, some research suggests that the negative effects of peer victimization on mental health could be worse precisely in those schools making a higher effort to reduce bullying, a phenomenon known as the safe school paradox (Huitsing et al., Reference Huitsing, Lodder, Oldenburg, Schacter, Salmivalli, Juvonen and Veenstra2019; Juvonen & Schacter, Reference Juvonen and Schacter2020), with potential explanations ranging from attacks being more concentrated in a small number of students to increased self-blame in targets of bullying to fewer opportunities for targets to find friends facing similar adversities (Garandeau & Salmivalli, Reference Garandeau and Salmivalli2019).

The present study

The present study analyzes two-year longitudinal data from the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development Study® (ABCD: abcdstudy.org) (Saragosa-Harris et al., Reference Saragosa-Harris, Chaku, MacSweeney, Guazzelli Williamson, Scheuplein, Feola and Mills2022; Volkow et al., Reference Volkow, Koob, Croyle, Bianchi, Gordon, Koroshetz and Weiss2018) to (1) examine associations between peer victimization and changes in mental health symptoms (i.e. symptoms of major depression disorder (MDD), separation anxiety (SA), prodromal psychosis (PP), and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)) and explore how the magnitude of these associations changes by the recency and intensity of experiences of peer victimization, and (2) test whether different systems of social support (i.e. parental warmth, prosocial school environment) moderate these associations.

First, building on prior studies showing a positive association between peer victimization and multiple mental health symptoms (Christina, Magson, Kakar, & Rapee, Reference Christina, Magson, Kakar and Rapee2021; Cunningham, Hoy, & Shannon, Reference Cunningham, Hoy and Shannon2016; Liao, Chen, Zhang, & Peng, Reference Liao, Chen, Zhang and Peng2022; Reijntjes, Kamphuis, Prinzie, & Telch, Reference Reijntjes, Kamphuis, Prinzie and Telch2010; Ttofi, Farrington, & Lösel, Reference Ttofi, Farrington and Lösel2012), and theories describing how peer victimization could lead to more mental health symptoms under a multi-finality framework (LoParo et al., Reference LoParo, Fonseca, Matos and Craighead2023), we predicted that peer victimization would be associated with increases in all four mental health symptoms.

We focused on these four mental health symptoms in order to maximize the range of distinguishable mental health symptoms according to the Hierarchical Taxonomy Of Psychopathology (HiTOP) at the spectra and subfactor levels (for more details see Supplemental section 1). HiTOP is a dimensional model of mental health problems designed to increase symptom specificity and reduce boundary problems across the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) categories (Conway et al., Reference Conway, Forbes, Forbush, Fried, Hallquist, Kotov and South2019; Kotov et al., Reference Kotov, Krueger, Watson, Achenbach, Althoff, Bagby and Clark2017). Specifically, we centered on MDD as a problem of distress at the subfactor level within internalizing problems at the spectra level, on SA as a fear disorder at the subfactor level within the same spectra as MDD, on PP as a thought disorder at the spectra level, and ADHD as an antisocial behavior within externalizing problems at the spectra level (Conway et al., Reference Conway, Forbes, Forbush, Fried, Hallquist, Kotov and South2019; Kotov et al., Reference Kotov, Krueger, Watson, Achenbach, Althoff, Bagby and Clark2017; Michelini, Palumbo, DeYoung, Latzman, & Kotov, Reference Michelini, Palumbo, DeYoung, Latzman and Kotov2021).

Moreover, drawing from recent evidence reporting the existence of two distinctive processes of peer victimization at schools, with one being temporal lasting weeks to months, and another more distressing and persistent lasting years (Thornberg, Reference Thornberg2018; Thornberg, Bjereld, & Caravita, Reference Thornberg, Bjereld and Caravita2023), and quantitative studies suggesting stronger effects of peer victimization on mental health when experiences are more recent (Evans-Lacko et al., Reference Evans-Lacko, Takizawa, Brimblecombe, King, Knapp, Maughan and Arseneault2017; Singham et al., Reference Singham, Viding, Schoeler, Arseneault, Ronald, Cecil and Pingault2017) or intense (Dantchev, Zammit, & Wolke, Reference Dantchev, Zammit and Wolke2018; Gorman, Harmon, Mendolia, Staneva, & Walker, Reference Gorman, Harmon, Mendolia, Staneva and Walker2021), we predicted that more recent or intense exposure to peer victimization would be linked to the development of more mental health symptoms over time.

Second, we tested whether parental warmth and a prosocial school environment would moderate the associations between peer victimization and changes in mental health symptoms over time. Building on the stress-buffering (Cohen & Wills, Reference Cohen and Wills1985; Guo et al., Reference Guo, Li, Wang, Ma and Ma2020) and youth resilience (Kochel et al., Reference Kochel, Bagwell, Ladd and Rudolph2017; Masten et al., Reference Masten, Lucke, Nelson and Stallworthy2021) models, we expected parental warmth and prosocial school environments to buffer these longitudinal associations. However, we note that findings in the peer victimization literature regarding the moderating role of support from families and schools have been inconclusive (e.g. Guo et al., Reference Guo, Li, Wang, Ma and Ma2020; Rudolph et al., Reference Rudolph, Monti, Modi, Sze and Troop-Gordon2020), and that heterogeneity across different mental health symptoms has been previously reported (e.g. Davidson & Demaray, Reference Davidson and Demaray2007).

Existing studies drawing from the ABCD data have provided important insights into how social contexts affect mental health directly (Conley, Hernandez, Salvati, Gee, & Baskin-Sommers, Reference Conley, Hernandez, Salvati, Gee and Baskin-Sommers2022; Vargas & Mittal, Reference Vargas and Mittal2021; Vargas, Damme, & Mittal, Reference Vargas, Damme and Mittal2022) and moderate mental health effects (Assari, Boyce, Bazargan, & Caldwell, Reference Assari, Boyce, Bazargan and Caldwell2020; Conley et al., Reference Conley, Hindley, Baskin-Sommers, Gee, Casey and Rosenberg2020; Lin et al., Reference Lin, Schleider and Eaton2021; Rakesh et al., Reference Rakesh, Seguin, Zalesky, Cropley and Whittle2021; Stinson et al., Reference Stinson, Sullivan, Peteet, Tapert, Baker, Breslin and Lisdahl2021) but no prior studies focused on peer victimization as a predictor of changes in symptoms of multiple mental health categories and the moderating roles of family and school support.

Methods

Sample

The present study used data from the ABCD study, which was designed to track the developmental trajectories of nine- to ten-year-old children living in 21 cities across the US (Garavan et al., Reference Garavan, Bartsch, Conway, Decastro, Goldstein, Heeringa and Zahs2018; Karcher & Barch, Reference Karcher and Barch2020). Data collection began in 2016 and is intended to continue for ten years as children transition into their early adulthood. The analysis in this article is based on the data from baseline and the first two annual follow-ups (i.e. curated data 4.0). Children verbally consented to the study, their parents gave written informed consent, and each of the 21 local institutional review boards certified that the study complied with the biomedical ethics requirements involved in research with human subjects (Clark et al., Reference Clark, Fisher, Bookheimer, Brown, Evans, Hopfer and Yurgelun-Todd2018).

The ABCD study recruited a sample of 11 844 children and their primary caregivers in 21 cities in the US. The research design involved different strategies for recruiting single births and twins. The baseline sample comprises 9676 single births, with 1809 corresponding to siblings of other participants, 2138 twins, and 30 triplets. The sampling and recruitment strategies for single births usually involved recruiting 3rd and 4th-grade students in randomly selected schools from catchment areas typically within 50 mile-radius from any of the 21 research sites in the study (Garavan et al., Reference Garavan, Bartsch, Conway, Decastro, Goldstein, Heeringa and Zahs2018; Karcher & Barch, Reference Karcher and Barch2020). For the case of twins and triplets, the recruitment strategy relied on four centers with more than 30 years of experience conducting twin research (Iacono et al., Reference Iacono, Heath, Hewitt, Neale, Banich, Luciana and Bjork2018).

To increase participants retention over time and reduce potential threats to validity, generalizability, and selection bias, the ABCD study team established a framework aiming to foster and maintain strong relationships with youth and caregivers based on positive interactions, building of rapport, frequent interaction with families, keeping detailed locator information up to date, and close monitoring of hard-to-reach populations (Ewing et al., Reference Ewing, Chang, Cottler, Tapert, Dowling and Brown2018). Despite these retention efforts, data were incomplete due to attrition and non-response for some of the variables. Two alternative approaches were followed to assess how missing data could affect the results. First, we conducted complete-case analyses (i.e. including observations for which all measurements were recorded) using different groups of covariates capturing a common group of potential confounders that vary on their non-response rate (N = 8385 to 9391). Second, we used a multiple imputation strategy that combines results from ten ‘completed’ datasets (N = 11 844). Supplementary section 2 presents more details on data missingness patterns. Overall, white children from higher-income families who had caregivers with higher levels of education were less likely to have incomplete data.

Measures

Mental health

Mental health symptoms were assessed at baseline and two years later using the computerized adaptation of the Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (KSADS-5) (Kaufman, Townsend, & Kobak, Reference Kaufman, Townsend and Kobak2017; Mennies, Birk, Norris, & Olino, Reference Mennies, Birk, Norris and Olino2021) and the brief version of the Prodromal Questionnaire (PQ-B) (Loewy, Pearson, Vinogradov, Bearden, & Cannon, Reference Loewy, Pearson, Vinogradov, Bearden and Cannon2011). Specifically, symptoms of MDD (ten symptoms; Cronbach's alpha at baseline (α 0) = 0.77; and Cronbach's alpha at the two-year follow-up (α 2) = 0.78); SA (eight symptoms; α0 = 0.75; α 2 = 0.74); and ADHD (18 symptoms; α 0 = 0.95; α 2 = 0.95) were assessed using the computerized version of the KSADS-5 (Kaufman et al., Reference Kaufman, Townsend and Kobak2017; Mennies et al., Reference Mennies, Birk, Norris and Olino2021). The KSADS-5 is a self-administered diagnostic interview conducted separately with youth and primary caregivers. Children's reports were prioritized and used to assess symptoms of MDD and PP, and caregiver reports were used to assess SA and ADHD, given the lack of youth reports for these latter symptoms. Previous studies show high diagnostic agreement with the clinician-administered version in the range of 88 to 96% (Barch et al., Reference Barch, Albaugh, Avenevoli, Chang, Clark, Glantz and Alia-Klein2018). Symptoms of prodromal psychosis were measured using the distress score from the brief version of the Prodromal Questionnaire (PQ-B) (Loewy et al., Reference Loewy, Pearson, Vinogradov, Bearden and Cannon2011) (PP; 21 items; α 0 = 0.86; α 2 = 0.86).

Peer victimization

Peer victimization was measured using items from the child behavior checklist (CBCL), a questionnaire completed by caregivers that assess their child's behavioral, social, and emotional problems (Achenbach & Rescorla, Reference Achenbach and Rescorla2001; Michelini et al., Reference Michelini, Barch, Tian, Watson, Klein and Kotov2019). Building on prior work (Levitan, Barkmann, Richter-Appelt, Schulte-Markwort, & Becker-Hebly, Reference Levitan, Barkmann, Richter-Appelt, Schulte-Markwort and Becker-Hebly2019; McCloskey & Stuewig, Reference McCloskey and Stuewig2001; Papadopoulos, Seguin, Correa, & Duerden, Reference Papadopoulos, Seguin, Correa and Duerden2021; van Gent, Goedhart, & Treffers, Reference van Gent, Goedhart and Treffers2011), peer victimization was measured at baseline using the peer victimization subscale embedded in the social problems subscale (3 items; gets teased a lot; not liked by other kids; does not get along with others; 0 = Not true, 1 = Somewhat or sometimes true, 2 = Very true or often true; α 0 = 0.71). The main longitudinal and moderation analyses of the study were conducted using the average of these three items at baseline.

To explore how recency or intensity of peer experiences would affect the progression of mental health symptoms, we examined three other operationalizations for peer victimization: (1) a binary variable (1 = if a child experienced any of the three situations of peer victimization mentioned above, 0 = otherwise). We created two separate binary peer victimization variables based on data from baseline and the one-year follow-up; (2) a categorical variable measuring differences in how recent the peer victimization occurred (0 = no exposure to peer victimization at baseline nor the one-year follow-up, 1 = child experiences any of the three situations of peer victimization mentioned above at baseline but not at the one-year follow-up, 2 = child experiences these situations at the one-year follow-up but not at baseline, 3 = child experiences any of these forms of peer aggression at both periods); (3) a categorical variable capturing differences in the intensity or frequency of peer victimization (0 = no experiences of peer victimization, 1 = none of the three experiences occur often, 2 = any of the three experiences occur often). Like in operationalization (1), we created two separate variables based on data from baseline and the one-year follow-up.

Moderators

Parental warmth was measured using the Acceptance Subscale of the Child Report of Behavior Inventory (5 items per primary and secondary caregiver; e.g. makes me feel better after talking over my worries with him/her; 1 = Not like him/her, 2 = Somewhat like him/her, 3 = A lot like him/her; α 0 = 0.79) (Zucker et al., Reference Zucker, Gonzalez, Ewing, Paulus, Arroyo, Fuligni and Wills2018). Prosocial school environment was measured by youth reports based on the subscales of opportunities and rewards for prosocial involvement (6 items; e.g. lots of chances for students to get involved in sports, clubs, or other activities outside of class; 1 = NO!, 2 = no, 3 = yes, 4 = YES! – with capitalized responses meaning that the statement is definitely true, and little letter if it is mostly true; α 0 = 0.61) within the communities that care youth survey (Arthur et al., Reference Arthur, Briney, Hawkins, Abbott, Brooke-Weiss and Catalano2007).

Covariates

Analyses controlled for a wide range of variables. The inclusion of covariates was informed by the empirical evidence relating these factors to both peer victimization (Álvarez-García, García, & Núñez, Reference Álvarez-García, García and Núñez2015; Arseneault, Reference Arseneault2017; Saarento, Garandeau, & Salmivalli, Reference Saarento, Garandeau and Salmivalli2015; Zych, Farrington, Llorent, & Ttofi, Reference Zych, Farrington, Llorent and Ttofi2017) and mental health (Lilienfeld & Treadway, Reference Lilienfeld and Treadway2016; Lund et al., Reference Lund, Brooke-Sumner, Baingana, Baron, Breuer, Chandra and Saxena2018; Rasic, Hajek, Alda, & Uher, Reference Rasic, Hajek, Alda and Uher2014; Richter & Dixon, Reference Richter and Dixon2022) in order to reduce potential bias from confounders. Following this rationale and the relevant empirical evidence, twenty-one variables measured at baseline were selected for inclusion, with none of them showing high levels of collinearity between each other after a variance inflation factor analysis (See Supplemental section 3).

Covariates included child mental health variables measured at baseline from the CBCL excluding the social problems scale (i.e. internalizing and externalizing symptoms, symptoms of thought problems, and attention problems), the outcome of interest measured at baseline using the corresponding KSADS-5 or PQ-B scales, sex at birth indicator (0 = male, 1 = female), a binary variable for race (1 = white, and 0 = otherwise), age, a puberty index based on the Youth Pubertal Development Scale and Menstrual Cycle Survey History (Petersen, Crockett, Richards, & Boxer, Reference Petersen, Crockett, Richards and Boxer1988); an indicator for the presence of a sibling in the study (0 = No, 1 = Yes); annual family income per capita (in US dollars), educational attainment of the primary caregiver (0 = high school or less, 1 = some college, 2 = associate degree, 3 = college, 4 = masters or more); mental health symptoms of the primary caregiver using age-corrected scores from the Achenbach Adult Self-report at baseline (Achenbach & Rescorla, Reference Achenbach and Rescorla2003); family conflict (using a subscale of the PhenX toolkit reported by youth, nine items; e.g. family members sometimes get so angry they throw things; 0 = No, 1 = Yes, α 0 = 0.70); and neighborhood deprivation index (as described in Kind et al., Reference Kind, Jencks, Brock, Yu, Bartels, Ehlenbach and Smith2014).

In choosing our main specification and the list of covariates, we sought to achieve a parsimonious model that avoids over adjustment bias but controls for relevant determinants of baseline peer victimization that could also be related to mental health symptoms at the two-year follow-up. Regarding key demographic variables, we opted to use sex at birth because alternative measures of gender identity or sexual orientation have been reported as not developmentally appropriate by the ABCD study workgroup of Gender Identity and Sexual Health (Potter et al., Reference Potter, Dube, Barrios, Bookheimer, Espinoza, Ewing and Johns2022). Similarly, we followed prior work and included a white race indicator as a potential confounder aiming to capture social majority privilege in the US context, without attempting to control for potential differences between other racial minority categories (e.g. Espelage, Hong, Kim, & Nan, Reference Espelage, Hong, Kim and Nan2018; Rosen & Nofziger, Reference Rosen and Nofziger2019; Vitoroulis & Vaillancourt, Reference Vitoroulis and Vaillancourt2018). Nonetheless, we tested the robustness of our main findings to the use of different sets of covariates [see Supplemental section 4 (SS4)] and to alternative measures of gender identity and race (SS4, specification 6).

Statistical analysis

We followed a longitudinal approach to study the progression of symptoms. This strategy ensures that the regressors are determined before the realization of changes in symptoms, minimizing the risk of simultaneity bias. Specifically, two sets of longitudinal analyses were performed. First, longitudinal associations were calculated separately between peer victimization operationalized in different ways and each of the four mental health outcomes two years later, controlling for an extensive list of potential confounders, including the outcome of interest measured at baseline for youth and caregivers. Our approach to conducting independent regression analyses was supported by low correlations between error terms between the four separate regressions, suggesting a relevant degree of specificity for each of the outcomes (See Supplemental section 5). To reduce concerns regarding the potential discovery of statistically significant results by chance while testing multiple hypotheses, we implemented the Bonferroni correction for four outcomes. Models were fitted using multilevel mixed-effects linear regression with varying intercepts and children nested within families and families nested within research sites (Heeringa & Berglund, Reference Heeringa and Berglund2020). The estimations were performed by maximum likelihood using the Stata command MIXED. In follow-up analyses, we examined the magnitude of the link between peer victimization and mental health symptoms using different operationalizations of peer victimization. Specifically, we use binary and categorical variables that intend to capture differences in the intensity and recency of exposure to peer victimization.

Second, after examining the relationship between peer victimization exposure and subsequent development of mental health symptoms, additional analyses tested whether two types of social support buffered this link. The moderation analyses mirrored the multilevel strategy described above, using the average of the three items measured at baseline for peer victimization, including the same covariates, and independently (in separate models) adding an interaction term between peer victimization and each of the moderators (i.e. parental warmth and prosocial school environment), both measured at baseline.

Lastly, for the main analyses concerning two-year longitudinal associations and moderation effects, six alternative models were estimated to assess the robustness of the results to the use of different sets of covariates and imputation of missing data [SS4 describes each model and presents their results along with those from our main model described in this section, as reference (see specification 1)]. Including different sets of covariates helps mitigate concerns related to missing values due to different non-response rates among the confounders. Similarly, conducting multiple imputation contributes to reducing potential bias from missingness and improves the precision of estimates (Cummings, Reference Cummings2013; Pedersen et al., Reference Pedersen, Mikkelsen, Cronin-Fenton, Kristensen, Pham, Pedersen and Petersen2017). Our approach to multiple imputation assumes a multivariate normal distribution for the missing values to calculate plausible values for them and create ten completed data sets. Then, analysis is performed in each of these data sets. The ten estimates of interest are combined into a single inference by applying Rubin's rules (De Vaus, Reference De Vaus2002; von Hippel, Reference von Hippel2013).

Results

Preliminary analyses and sample characteristics

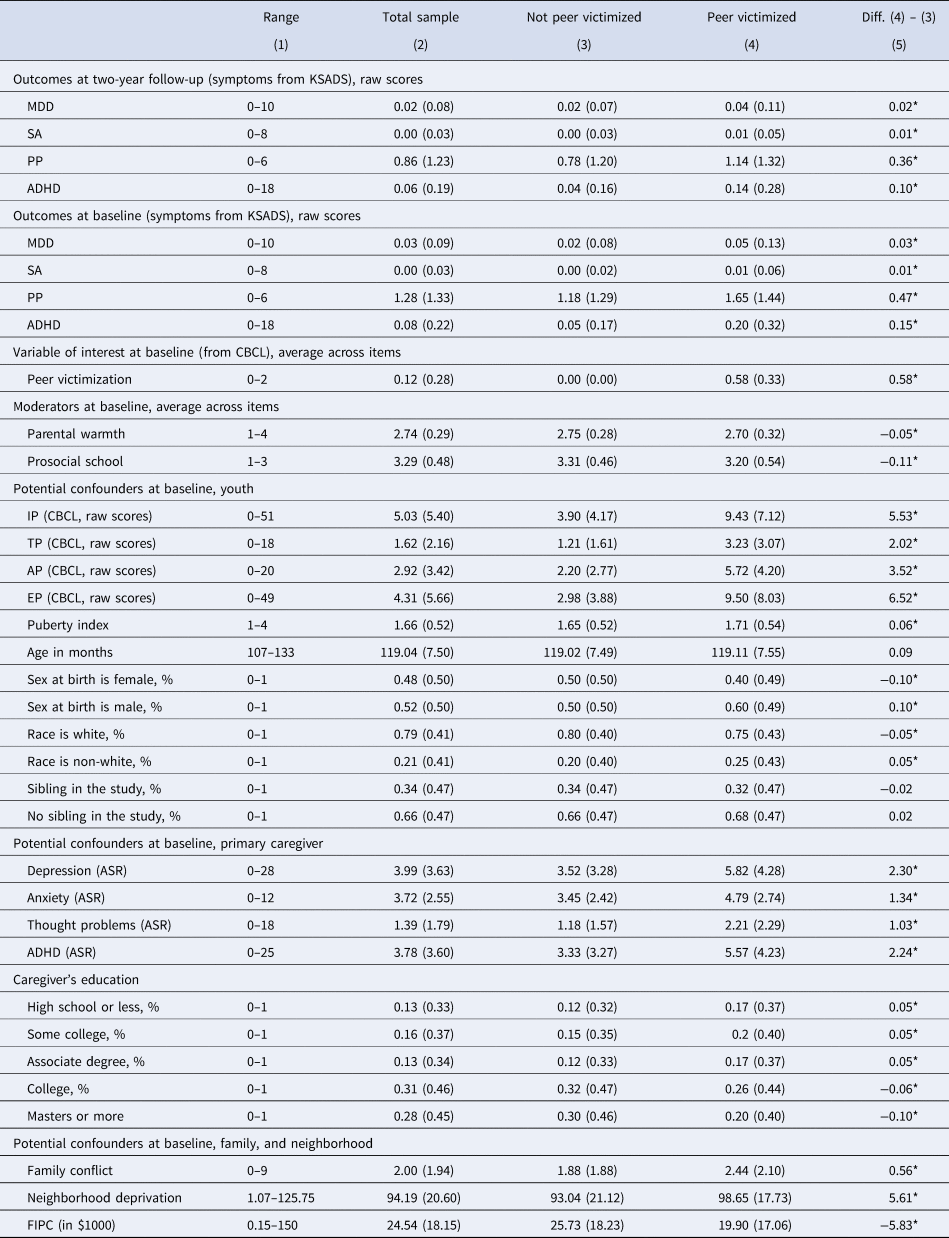

A total of 8385 children out of the 11 844 in the ABCD study at baseline had data on all the variables relevant for analysis and were used in the main statistical analyses (results were generally robust when using different sets of covariates and multiple imputation, see SS4). The demographic characteristics of participants in the analytical sample are displayed in Table 1. Overall, 20% of children had experienced some type of peer victimization at baseline. Compared to children who did not experience peer victimization, children who experienced peer victimization were more likely to be boys, non-white, live in more deprived neighborhoods, have higher mental health symptoms at baseline, attend less prosocial schools, and have caregivers who are less warm with lower education and higher mental health symptoms (to provide further details, a multivariate approach estimating risk ratios of being victimized by peers is presented in Supplemental section 6, and a pairwise correlations between the main variables is reported in Supplemental section 7).

Table 1. Sample characteristics at baseline

KSADS, Kiddie schedule for affective disorders and schizophrenia; MDD, major depressive disorder; SA, separation anxiety; PP, prodromal psychosis; ADHD, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; IP, internalizing problems; TP, thought problems; AP, attention problems; EP, externalizing problems; CBCL, Child behavior checklist Aseba; ASR, adult self-report Aseba; FIPC, family income per capita.

* : Difference statistically significant between non-victims and victims at the 95% confidence level, according to t tests for mean differences.

Longitudinal associations

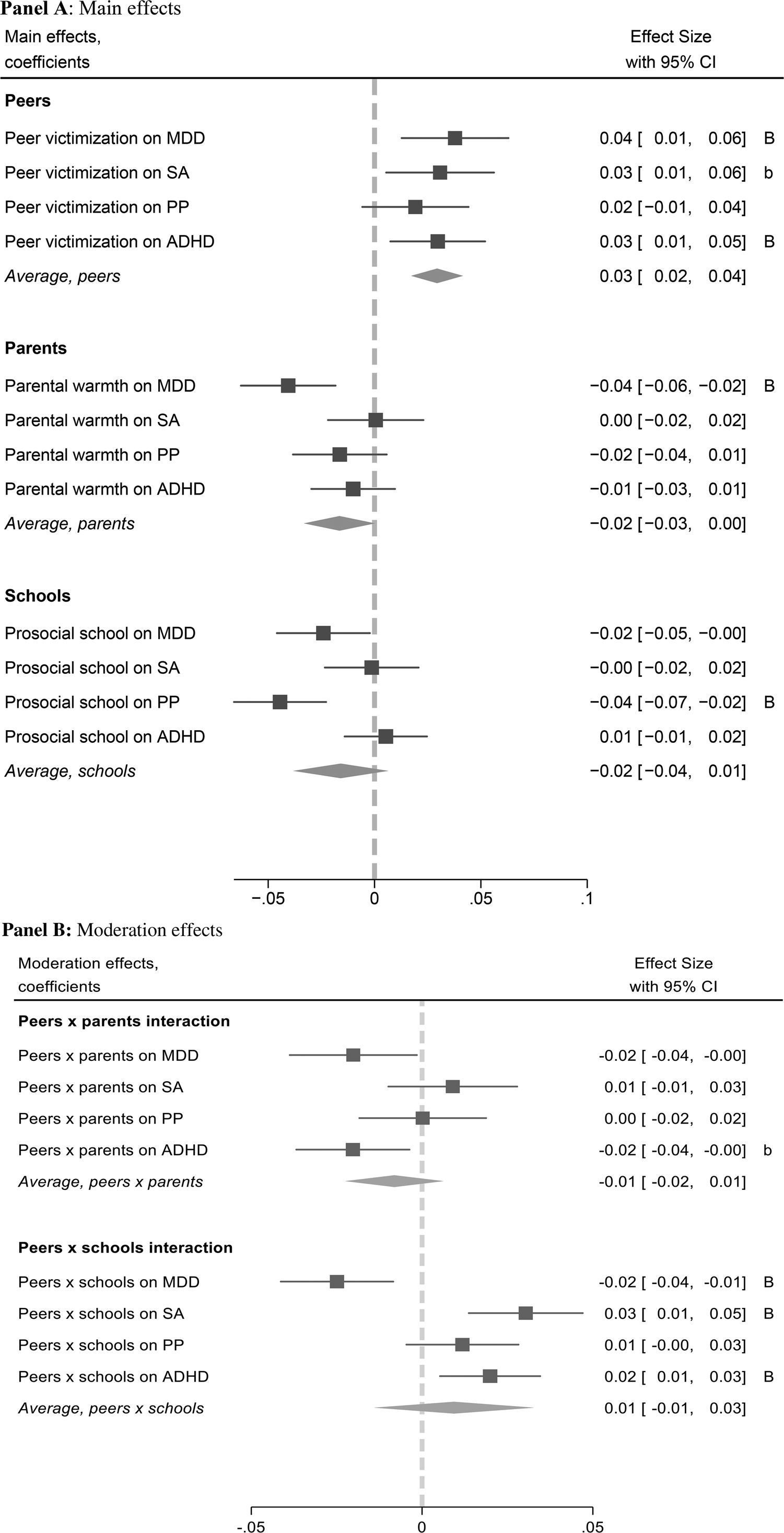

Figure 1a presents the longitudinal associations (i.e. standardized regression coefficients) between exposure to peer victimization and mental health symptoms based on linear mixed models and our preferred operationalization of peer victimization (i.e. average of the three items measured at baseline). Supplemental section 8 (SS8) also presents the same estimates of interest along with the coefficients for each of the covariates.

Figure 1. Longitudinal associations between peer victimization and mental health symptoms. (a) Main effects. (b) Moderation effects.

Notes: Graph shows the standardized regression coefficients from the linear mixed model described in the methods section. All estimations (Panel A and B) control for the following child variables measured at baseline: symptoms of the corresponding outcome, symptoms of internalizing, externalizing, thought and attention problems, sex at birth, age, race, neighborhood deprivation, family conflict, family income per capita, puberty index, and presence of a sibling participating in the study. It also controls for the primary caregiver's symptoms of the corresponding mental health problem and her/his education level; both measured at baseline. Peer victimization, parental warmth, school environment, and mental health variables were standardized, so their mean is zero and standard deviation one.

*p < 0.1; **p < 0.05; ***p < 0.01.

B:Coefficient statistically significant for a significance level of 0.05 after the Bonferroni correction for a collection of four null hypotheses.

b:Coefficient statistically significant for a significance level of 0.10 after the Bonferroni correction for a collection of four null hypotheses.

MDD, major depressive disorder; SA, separation anxiety; PP, prodromal psychosis; ADHD, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder.

The main results showed that an increase in one standard deviation in the peer victimization variable at baseline was associated with an increase in MDD symptoms [standardized coefficient (s.e.), 0.038 (0.013); 95% CI 0.013–0.063), SA (0.031 (0.013); 95% CI 0.005–0.056), and ADHD (0.030 (0.011); 95% CI 0.008–0.052) two years later, after including all confounders listed in Table 1. For PP, the longitudinal associations were positive across specifications but were not statistically significant (Fig. 1a and SS8). Associations between peer victimization and MDD as well as ADHD symptoms survived the Bonferroni correction for an overall significance level of 0.05.

The results also showed that higher parental warmth was associated with fewer symptoms of MDD [−0.041 (0.011); 95% CI −0.046 to −0.002], and a more prosocial environment at school was associated with fewer symptoms of PP [−0.044 (0.011); 95% CI −0.066 to −0.023]. Four out of the six remaining coefficients related to caregivers' warmth, schools' prosociality, and mental health categories were also negative; however, they were not statistically significant across most specifications (Fig. 1a, and SS8). Associations between parental warmth and MDD symptoms as well as prosocial school environment and PP symptoms, survived Bonferroni corrections for an overall significance level of 0.05 (see Fig. 1a).

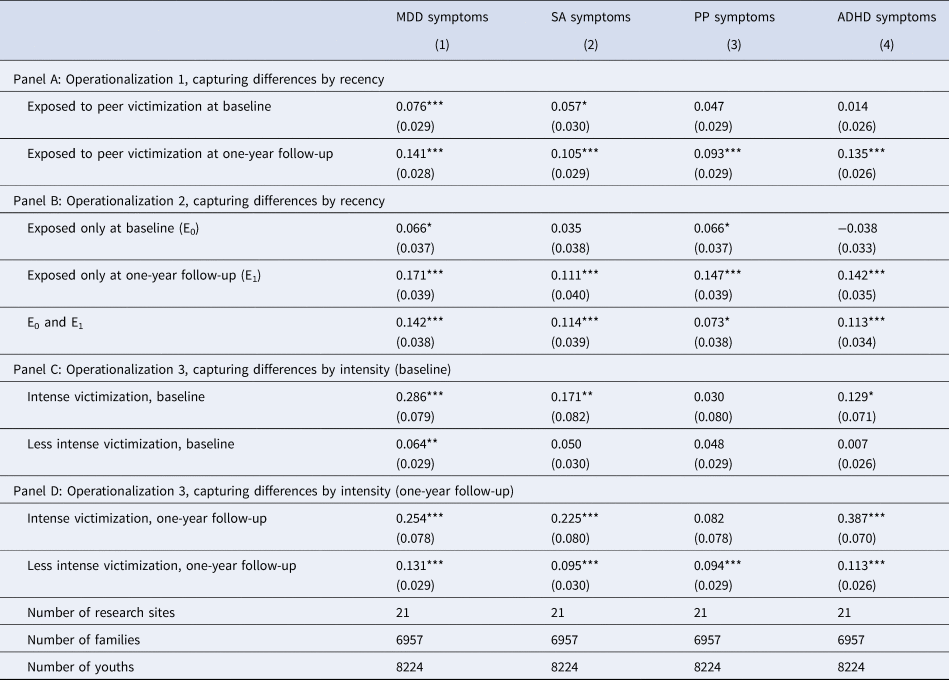

Recency and intensity of experiences

Three alternative operationalizations of peer victimization were used to explore how longitudinal associations between exposure to peer victimization and changes in mental health symptoms varied by the recency and intensity of experiences, after controlling for the potential confounders described above. First, peer victimization was operationalized as a binary indicator of experiencing at least one of the three types of peer victimization under study, at baseline or at the one-year follow-up (see Table 2, Panel A). Results showed a positive association between these variables and the development of mental health symptoms in the four outcomes we studied. The associations were positive with magnitudes twice as much when peer victimization was measured at the one-year follow-up [for instance, when peer victimization was measured at baseline, the coefficient capturing the two-year increase in MDD symptoms was 0.076; standard error (s.e. = 0.029); confidence interval (CI) 0.019–0.133, compared to 0.141 (0.028); CI 0.089–0.199, for peer victimization measured at the one-year follow-up]. For symptoms of SA, PP, and ADHD at baseline, the positive associations are not statistically significant at conventional levels (significance level of 0.05).

Table 2. Main results using alternative operationalizations for peer victimization

MDD, major depressive disorder; SA, separation Anxiety; PP, prodromal psychosis; ADHD, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder.

Notes: Estimations are based on complete-case analysis and linear mixed models. The number of observations differs from those reported in Table 1 due to additional missing values in the peer victimization variable measured at the one-year follow-up. In Panel A, each cell corresponds to the same regression. In Panels B, C, and D, each column corresponds to the same regression. Coefficients in all panels are interpreted using ‘No peer victimization’ as the reference category. All estimations control for the following child variables measured at baseline: symptoms of the corresponding outcome, symptoms of internalizing, externalizing, thought and attention problems, sex at birth, age, race, neighborhood deprivation, family income per capita, family conflict, puberty index, and presence of a sibling participating in the study. It also controls for parental warmth, school environment, and the primary caregiver's education level. Mental health variables were standardized, so their mean is zero and standard deviation one. ∗ p < 0.1; ∗∗ p < 0.05; ∗∗∗ p < 0.01.

The second operationalization was based on a categorical variable examining exposure to peer victimization at baseline, one-year follow-up, or both. Results showed that peer victimization at baseline was linked to marginal increases in mental health symptoms two years later [for example, in MDD: 0.066 (0.037); CI −0.001 to 0.139]. Exposure at both periods was associated with a significant increase in mental health symptoms across outcomes (p < 0.05). Interestingly, there were no significant differences in the coefficients capturing the longitudinal associations between children exposed to peer victimization at both time points [in MDD: 0.142 (0.038); CI 0.068–0.216] and those exposed only at the one-year follow-up [in MDD: 0.171 (0.039); CI 0.095–0.247]. For more details, see Table 2, Panel B.

Lastly, the third operationalization attempted to capture differences in intensity by defining peer victimization based on the frequency of these experiences. Table 2, Panel C presents the results for experiences measured at baseline, and Panel D the corresponding results for the same experiences measured at the one-year follow-up. The results demonstrated stronger associations between exposure to peer victimization and mental health symptoms when the experiences were more frequent or intense [for instance, when peer victimization was measured at baseline the association between less intense experiences with increases in MDD symptoms was 0.064 (0.029); CI 0.007–0.121, compared to 0.286 (0.079); CI 0.131–0.441, for more intense experiences). The pattern of results also suggested that the association between exposure to peer victimization and mental health symptoms decreased more over time for less intense experiences than more frequent victimization [for instance, for less intense experiences, the association with two-year changes in MDD symptoms was 0.131 (0.029); CI 0.074–0.188 at the one-year follow-up, and 0.064 (0.029); CI 0.007–0.121 at baseline; the corresponding values for more intense victimization are 0.254 (0.078); CI 0.101–0.401 and 0.286 (0.079); CI 0.131–0.441, respectively].

Moderation analyses

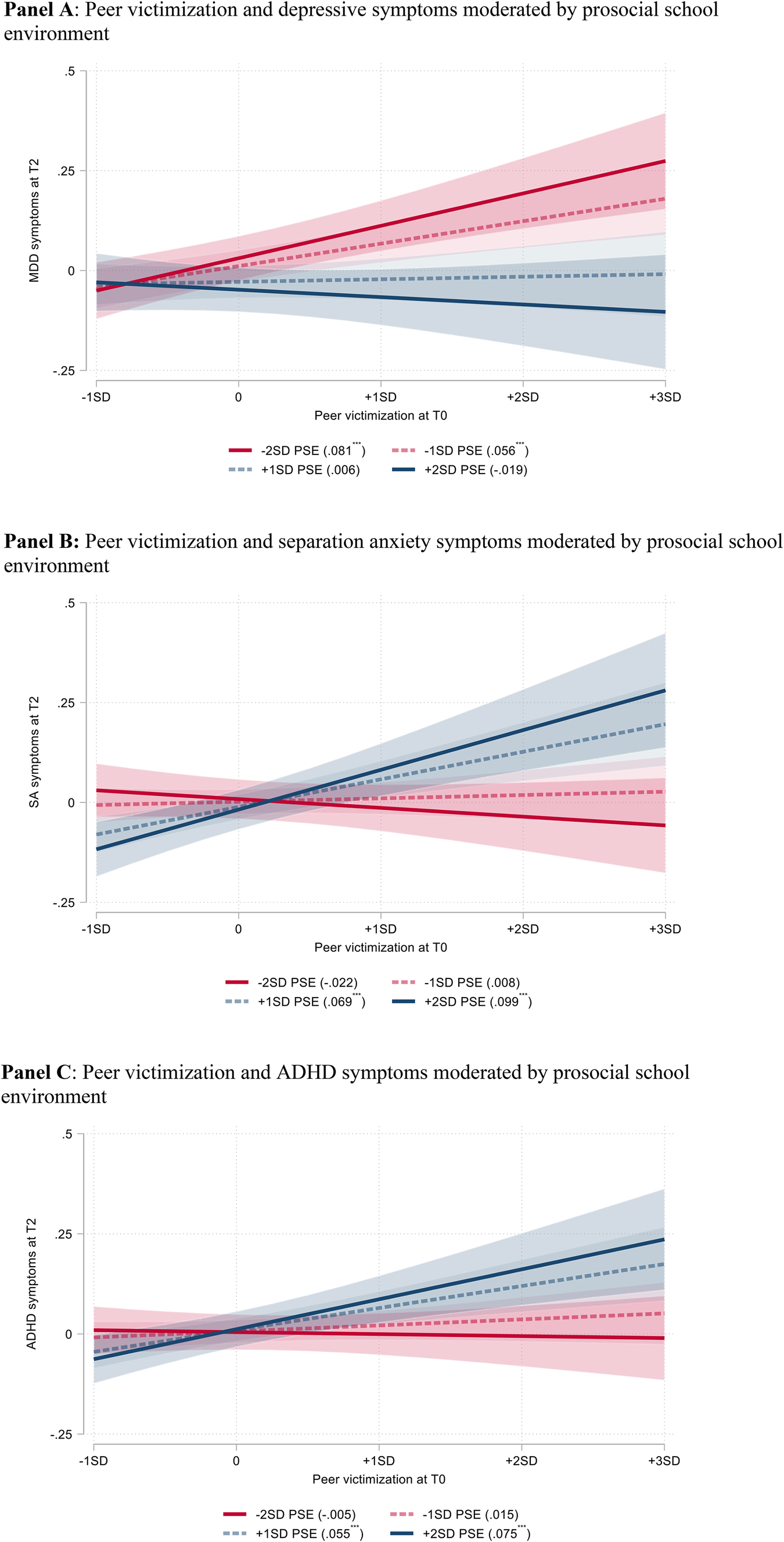

Moderation analyses followed the same approach as the longitudinal regression analyses, but for each of them, an interaction term between peer victimization and the moderator was added in separate models. The detailed results are shown in Supplemental section 9 (SS9) and indicate that higher levels of parental warmth attenuated the association between peer victimization and increases in MDD [interaction term (s.e.) −0.020 (0.009); 95% CI −0.038 to −0.002] and ADHD symptoms [−0.021 (0.008); 95% CI −0.037 to −0.004], but not other mental health symptoms (Fig. 1b). However, this moderation effect did not survive the Bonferroni correction. Similarly, a more prosocial school environment buffered the association between peer victimization and increases in MDD symptoms [−0.025 (0.008); 95% CI −0.041 to −0.008; Figure 2a] but exacerbated the association between peer victimization and SA symptoms [0.030 (0.008); 95% CI 0.014–0.047; Fig. 2b], and ADHD symptoms [0.020 (0.007); 95% CI 0.005–0.034; Fig. 2c]. No moderating effects emerged for other mental health outcomes (Fig. 1b and SS9). Interaction effects between prosocial school environment and MD, SA, and ADHD symptoms survived Bonferroni corrections (see Fig. 1b). Since Fig. 2 only presents plots for moderation effects that were statistically significant at conventional values (p < 0.05), the interested reader will find the plots for all associations between peer victimization and the four mental health symptoms studied as outcomes at different levels of parental warmth and prosocial school environment in eFigure 1 in Supplemental section 10.

Figure 2. Moderators for the link between peer victimization and mental health symptoms. (a) Peer victimization and depressive symptoms moderated by prosocial school environment. (b) Peer victimization and separation anxiety symptoms moderated by prosocial school environment. (c) Peer victimization and ADHD symptoms moderated by prosocial school environment.MDD, major depressive disorder; SA, separation anxiety; ADHD, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; PSE, prosocial school environment.Notes: Simple slopes shown in parenthesis within the graph legends.

*p < 0.1; **p < 0.05; ***p < 0.01.

Discussion

The transition to adolescence is a critical developmental period that may provide challenges and opportunities for mental health care. Based on a large-scale, longitudinal study, results showed that peer victimization was associated with the development of mental health symptoms across different domains of psychopathology beyond the contribution of other types of social disadvantages (e.g. family and area disadvantages) or caregiver's mental health. In particular, in the most conservative specification, an increase in one standard deviation in peer victimization at baseline was longitudinally associated with two-year increases up to 0.06 standard deviations in depressive, separation anxiety, and ADHD symptoms, a magnitude that can be characterized as potentially consequential in the not-very-long run (Funder & Ozer, Reference Funder and Ozer2019). These findings are consistent with several theories proposing negative interpersonal relationships as a key precursor of mental health problems (e.g. Andersen et al., Reference Andersen, Rasmussen, Reavley, Bøggild and Overgaard2021), and empirical evidence reporting links between peer victimization and these mental health symptoms (Christina et al., Reference Christina, Magson, Kakar and Rapee2021; Cunningham et al., Reference Cunningham, Hoy and Shannon2016; Liao et al., Reference Liao, Chen, Zhang and Peng2022; Reijntjes et al., Reference Reijntjes, Kamphuis, Prinzie and Telch2010, Reference Reijntjes, Kamphuis, Prinzie, Boelen, Van der Schoot and Telch2011; Ttofi et al., Reference Ttofi, Farrington and Lösel2012) as well as a number of plausible underlying mechanisms including the dysregulation of the stress response system (Rudolph et al., Reference Rudolph, Skymba, Modi, Davis, Sze, van Lier and Deater-Deckard2022; Zarate-Garza et al., Reference Zarate-Garza, Biggs, Croarkin, Morath, Leffler, Cuellar-Barboza and Tye2017), epigenetic modifications (Mulder et al., Reference Mulder, Walton, Neumann, Houtepen, Felix, Bakermans-Kranenburg and Cecil2020), changes in brain structures involved in emotion regulation (Mulkey & du Plessis, Reference Mulkey and du Plessis2019; Rudolph et al., Reference Rudolph, Skymba, Modi, Davis, Yan Sze, Rosswurm and Telzer2021), increased loneliness (Matthews et al., Reference Matthews, Caspi, Danese, Fisher, Moffitt and Arseneault2022), and decreased self-esteem (van Geel et al., Reference van Geel, Goemans, Zwaanswijk, Gini and Vedder2018).

It should be noted that associations between peer victimization and the development of prodromal psychosis symptoms were not statistically significant and associations with separation anxiety did not survive multiple test corrections, encouraging further exploration of the contexts in which these effects persist over time (Singham et al., Reference Singham, Viding, Schoeler, Arseneault, Ronald, Cecil and Pingault2017). Yet, our exploratory analyses varying how peer victimization was operationalized showed that longitudinal associations between exposure to peer victimization and symptoms of all four outcomes were considerably larger for youth who were exposed to more recent and more intense peer victimization. Moreover, the patterns of findings suggested that intense negative experiences with peers may have a more persistent contribution to the development of mental health symptoms over time. These findings underscore that effect sizes need to be interpreted in context and taking into account their sensitivity to different statistical specifications.

In addition to our aim of examining associations between peer victimization and mental health symptoms, our second aim was to examine the moderating roles of parental warmth and school environment. Parental warmth did predict longitudinal decreases in MDD symptoms across time but did not appear to buffer the negative mental health consequences of peer victimization, as none of the peer-victimization buffering effects initially found survived correction for multiple testing. Previous work has shown the physical health benefits of parental warmth in the face of adversity (Brody, Miller, Yu, Beach, & Chen, Reference Brody, Miller, Yu, Beach and Chen2016; Evans, Kim, Ting, Tesher, & Shannis, Reference Evans, Kim, Ting, Tesher and Shannis2007). The present findings suggest further exploration of the potential benefits of interventions targeting parenting skills (Kim, Schulz, Zimmermann, & Hahlweg, Reference Kim, Schulz, Zimmermann and Hahlweg2018; O'Farrelly et al., Reference O'Farrelly, Watt, Babalis, Bakermans, Barker, Byford and Ramchandani2020) for reducing MDD symptoms and encourage further examination of other types of parental support that may buffer the effects of peer victimization. In contrast, a prosocial school environment buffered the effects of peer victimization on the development of MDD symptoms, converging with findings from Romano, Angelini, Consiglio, and Fiorilli (Reference Romano, Angelini, Consiglio and Fiorilli2021) and suggesting that schools that provide students with opportunities for engaging in prosocial behavior can help mitigate the negative consequences of peer victimization in the development of MDD symptoms. However, similar to previous research showing that the consequences of peer victimization can be worse for remaining students exposed to peer victimization at schools with low bullying rates (Huitsing et al., Reference Huitsing, Lodder, Oldenburg, Schacter, Salmivalli, Juvonen and Veenstra2019), the present findings show that school environments encouraging children to play with each other and that provide more opportunities to engage in extracurricular activities may intensify symptoms of separation anxiety and ADHD among children victimized by peers, reminiscent of some previous findings in ADHD (Kofler, Larsen, Sarver, & Tolan, Reference Kofler, Larsen, Sarver and Tolan2015; Milledge et al., Reference Milledge, Cortese, Thompson, McEwan, Rolt, Meyer and Eisenbarth2019).

At a conceptual level, the divergent moderation effects emerging from prosocial school environments for depressive (distress-related) v. anxiety (fear-related) symptoms may point to the different pathways implicated in the development of depression and anxiety, respectively (e.g. Clark & Watson, Reference Clark and Watson1991; Melton, Croarkin, Strawn, & Mcclintock, Reference Melton, Croarkin, Strawn and Mcclintock2016), with reduced sensitivity to reward specific to the former and heightened sensitivity to threat more relevant to the latter (Shankman et al., Reference Shankman, Nelson, Sarapas, Robison-Andrew, Campbell, Altman and Gorka2013). In the context of our findings, a more prosocial school could represent an opportunity for more rewarding interactions with peers, which could result in a reduction in depressive symptoms among those having negative interactions with classmates. At the same time, this type of setting could also be perceived as a more threatening environment for a share of youth exposed to peer victimization. This possibility is particularly plausible in light of recent evidence showing that peer aggression from closer friends or ‘frenemies’ can be more consequential for the mental health of targets (Faris, Felmlee, & McMillan, Reference Faris, Felmlee and McMillan2020), and studies demonstrating a link between exposure to peer victimization and increased social threat sensitivity suggesting that these youth are more likely to interpret ambiguous signals as threatening (Schacter, Marusak, Borg, & Jovanovic, Reference Schacter, Marusak, Borg and Jovanovic2022).

In a similar vein, the exacerbation of ADHD symptoms among youth exposed to peer victimization at more prosocial schools is consistent with evidence showing that children with ADHD are at high risk of experiencing peer rejection (Grygiel, Humenny, Rębisz, Bajcar, & Świtaj, Reference Grygiel, Humenny, Rębisz, Bajcar and Świtaj2018) and less likely to receive social support from parents, teachers, and friends (Mastoras, Saklofske, Schwean, & Climie, Reference Mastoras, Saklofske, Schwean and Climie2018). Possibly, these children may have difficulties engaging in behaviors that are perceived as prosocial (Paap et al., Reference Paap, Haraldsen, Breivik, Butcher, Hellem and Stormark2013) and instead may engage in behaviors that are perceived as more aggressive, hostile, and impulsive (Linnea, Hoza, Tomb, & Kaiser, Reference Linnea, Hoza, Tomb and Kaiser2012). Under these circumstances, creating school environments that encourage positive interactions between peers may create additional stress and pose a challenge for children already rejected by peers who are also experiencing ADHD symptoms. In these cases, more resources and higher involvement from the school staff might be a requirement in order to achieve the intended goal of developing positive peer relationships.

While these findings await replication in future studies, they are reminiscent of what some have called the ‘safe school paradox’ (Juvonen & Schacter, Reference Juvonen and Schacter2020) and remind us to be cautious in viewing the promotion of positive school environments as a one-size-fits-all solution. Reducing negative peer interactions and their adverse consequences may be achieved by combining efforts to enhance positive school environments intended to increase bystanders' empathy with targeted interventions supporting youth at higher risk of peer victimization. In this line, interventions training children to disengage attention from threats have been effective in reducing anxiety and could be an appropriate strategy in some contexts (Bar-Haim, Morag, & Glickman, Reference Bar-Haim, Morag and Glickman2011). Similarly, play-based interventions involving caregivers of children diagnosed with ADHD have shown to improve children's prosocial skills (Leckey et al., Reference Leckey, McGilloway, Hickey, Bracken-Scally, Kelly and Furlong2019; Wilkes-Gillan, Bundy, Cordier, Lincoln, & Chen, Reference Wilkes-Gillan, Bundy, Cordier, Lincoln and Chen2016).

This study has multiple strengths, including the large-scale sample, longitudinal design, focus on a sensitive period in the development of mental health difficulties, specificity analysis related to multiple mental health outcomes, testing for multiple sources of social support, and the use of an extensive list of control variables including social interactions at school and home. The present study also has limitations, including the absence of peer relationship information during preschool and early elementary school, a timeframe limited to two years, the use of discrete mental health symptoms rather than a dimensional approach, and the use of parental reports of youth peer victimization. With regard to the latter, while studies have shown that caregiver reports can be a valid, reliable, and viable measure of children's peer victimization (e.g. Løhre, Lydersen, Paulsen, Mæhle, & Vatten, Reference Løhre, Lydersen, Paulsen, Mæhle and Vatten2011; Schacter et al., Reference Schacter, Marusak, Borg and Jovanovic2022; Shakoor et al., Reference Shakoor, Jaffee, Andreou, Bowes, Ambler, Caspi and Arseneault2011; Stapinski et al., Reference Stapinski, Bowes, Wolke, Pearson, Mahedy, Button and Araya2014), caregivers may not know the full extent of their involvement in peer aggression, especially as children grow up and become more independent (Demaray, Malecki, Secord, & Lyell, Reference Demaray, Malecki, Secord and Lyell2013; Houndoumadi & Pateraki, Reference Houndoumadi and Pateraki2001; Shakoor et al., Reference Shakoor, Jaffee, Andreou, Bowes, Ambler, Caspi and Arseneault2011). In this regard, it is important to consider analyzing alternative sources of information (self-reports, peers, teachers, parents), as each has advantages and disadvantages. Children's self-reports are likely to reflect actual experiences. Still, they tend to produce higher levels of victimization than peer reports and might be distorted if youth have biases originating in mental health symptoms or feel that reporting their experiences would be stressful, embarrassing, or could exacerbate their negative interactions (Casper et al., Reference Casper, Meter and Card2015; De Los Reyes & Prinstein, Reference De Los Reyes and Prinstein2004). Peer reports may be based on high levels of awareness of peer victimization events but might be affected by youth perceptions of reputation that may not change quickly, even after behaviors have changed. These reports may also be biased toward reporting more salient events or those occurring closer to the social circles of the reporter (Košir et al., Reference Košir, Klasinc, Špes, Pivec, Cankar and Horvat2020). Teachers as non-members of the family or peer group may have more objective views of peer victimization among their students; however, they might also be prone to distortions depending on their beliefs about aggressive behavior, when victimization occurs in contexts farther from their supervision or when aggression is less evident such as in the case of covert types of victimization (Troop-Gordon & Ladd, Reference Troop-Gordon and Ladd2015).

Finally, to continue advancing our understanding of how peer victimization affects mental health, future research should continue elucidating the neural, social, emotional, motivational, and cognitive mechanisms by which peer victimization contributes to the development of mental health symptoms and through which buffering factors exert their influence, not just during the transition to adolescence but also earlier. These studies could inform future prevention and intervention studies and may help elucidate social contexts that amplify or hamper the effects of anti-bullying programs.

Conclusion

This large-scale longitudinal study shows that children who have experienced peer victimization were more likely to experience increases in MDD and ADHD symptoms in the transition to adolescence. Parental warmth predicted decreases in MDD symptoms but did not robustly buffer against the effects of peer victimization. Prosocial school environments, in contrast, did buffer the negative effects of peer victimization on MDD symptoms, while at the same time amplifying effects on SA and ADHD symptoms. Future interventions aiming to reduce the negative consequences of peer victimization on mental health symptoms during the transition to adolescence may consider combining the promotion of safe environments with targeted interventions focused on students who face more difficulties when encouraged to interact with their peers.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291724000035.

Acknowledgements

We thank the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) and researchers working on the ABCD study for their outstanding contribution to the academic community. This work was supported by Institute for Innovations in Developmental Sciences Fellowship to M.M., the NIMH to K.D. (T32MH126368) and T.V. (F31MH119776), the National Institute of Health to C.M.H. and V.A.M. (R21MH115231), an NSF CAREER award to Y.Q. (BCS-1944644), a NARSAD Young Investigator Award from the Brain and Behavior Research Foundation to C.M.H., research fund from the Center for Culture, Brain, Biology, and Learning at Northwestern University to Y.Q. and C.M.H. We also appreciate valuable comments by attendees to the Annual Conference of the Society for Affective Science (April 2021) and the World Anti-Bullying Forum (November 2021).

Competing interest

None.