Introduction

Psychiatric or mental disorders are the leading cause of disease burden calculated by years lived with disability, and affected 970.8 million people worldwide (GBD, 2017). Psychiatric disorders have been a rising concern for China, accompanying its rapid economic growth, profound societal changes and expansion in the ageing population in the past few decades. A recent nationwide epidemiological study reported a 16.6% lifetime prevalence of mental disorders in adulthood in China (Huang et al., Reference Huang, Wang, Wang, Liu, Yu, Yan and Wu2019b). The disease burden of mental, neurological and substance use disorders in China accounted for 17% of the global disease burden in 2013, constituting 10% of its national disease burden (Charlson, Baxter, Cheng, Shidhaye, & Whiteford, Reference Charlson, Baxter, Cheng, Shidhaye and Whiteford2016).

Over the last two decades, the Chinese government has initiated a series of work plans to promote healthcare for mental disorders and to facilitate understanding of underlying mechanisms through neuroscience research (Fig. 1a). In 2005, the government launched a national public health programme to integrate community and hospital services for severe mental disorders, later referred to as the ‘686 Project’ (Ma, Reference Ma2012). In 2012, the first National Mental Health Law (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Phillips, Cheng, Chen, Chen, Fralick and Bueber2012) was endorsed by the National People's Congress which stipulates the rights of people with mental disorders and duties of healthcare providers at the legislative level (Shao, Wang, & Xie, Reference Shao, Wang and Xie2015; Xiang, Yu, Ungvari, Lee, & Chiu, Reference Xiang, Yu, Ungvari, Lee and Chiu2012). The National Mental Health Work Plans (2002–2010, 2015–2020) set principals and priorities of mental health work (Health, Affairs, & Security, 2003; Xiong & Phillips, Reference Xiong and Phillips2016). In 2016, the government announced the Outline of the Healthy China 2030 Initiative, in which promoting psychological well-being is one of the 15 targets to be achieved within the next decade (Chen, Li, & Harmer, Reference Chen, Li and Harmer2019; The State Council, 2019).

Fig. 1. (a) Milestones of mental health services and research in China in the past three decades. (b) Mental health clinics annual visits and facilities increase from 2007 to 2018. Data from the China Health Statistical Yearbook (National Health Commission, 2019). (c) Number of papers published in international peer-reviewed journals in the neuroscience field for four countries (USA, China, UK and Germany) from 1996 to 2019. (d) Number of papers published in neuroscience field (circle size) in top 20 countries with the highest H index (y-axis) in 2019. Data of (c–d) are from https://www.scimagojr.com/.

With the implementation of these regulations and initiatives, profound changes have occurred in psychiatric research and clinical services. On the clinical side, China has achieved significant progress in making healthcare services accessible and affordable to a great number of patients. A nationwide management system for severe mental disorders was established (Liang, Mays, & Hwang, Reference Liang, Mays and Hwang2018; Luo, Law, Lin, Yao, & Wang, Reference Luo, Law, Lin, Yao and Wang2017; Ma, Reference Ma2012). The number of annual visits to psychiatric clinics grew from 17.52 to 53.52 million from 2007 to 2018, and the number of hospital beds in psychiatry department increased from 0.16 to 0.51 million during the same period (National Health Commission, 2019) (Fig. 1b). Psychiatric health care professionals will reach 4.5 per 100 000 people by 2030 (The State Council, 2019).

Research into psychiatric disorders is an integral part of brain projects across the world. For example, the second phase of the NIH BRAIN initiative proposed the goal to understand brain disorders through understanding the basic mechanisms underlying the function of the healthy brain. The China Brain Project, entitled ‘Brain Science and Brain-Inspired Intelligence’, is a 15-year research plan (2016–2030) with a core theme and two principal areas of applications. The purpose of the China Brain Project is to enhance the understanding of neural circuit mechanisms of cognition, and based on this foundation, to further develop preventive, diagnostic and therapeutic approaches to brain disorders and to advance brain-inspired intelligence technologies (Poo et al., Reference Poo, Du, Ip, Xiong, Xu and Tan2016). Two national brain research centres in Beijing and Shanghai and several local research centres have been established with the launch of the China Brain Project. Neuroscience research has witnessed a rapid growth in the past three decades. Annual publication numbers in neuroscience from China increased exponentially from 227 in 1996 to 11 849 in 2019, ranking the second after the USA (SCImago, n.d.) (Fig. 1c). However, in terms of citation per document and H index, China is still lagging behind among the top 20 counties with the highest H index (SCImago, n.d.) (Fig. 1d).

The landscape of Chinese psychiatric research together with the healthcare system underwent unprecedented changes in the last few decades (Liu et al., Reference Liu, Ma, He, Xie, Xu, Tang and Yu2011). Such progress is indispensable to the development of global mental healthcare and research (Collins et al., Reference Collins, Patel, Joestl, March, Insel, Daar and Walport2011). As China makes one-seventh of the world's population, its ability to provide high-quality clinical services is part of the global efforts to achieve universal coverage for mental disorders (World Health Organization, 2013). Meanwhile, Chinese researchers are making a growing contribution to the neuroscience community. A number of reviews and commentaries have described achievements and challenges in mental health in China from different perspectives (Liu et al., Reference Liu, Ma, He, Xie, Xu, Tang and Yu2011; Que, Lu, & Shi, Reference Que, Lu and Shi2019; Shi, Reference Shi2019; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Xia, Chen, Dai, Qiu, Meng and Chen2019a, Reference Wang, Zhang, Liu, Crow, Zhang, Palaniyappan and Lib, Reference Wang, Hao, Li and Yuc, Reference Wang, Shi, Xu, Fu, Zeng and Zhengd). Yet, this review aims to provide an overall depiction of psychiatric research and healthcare system in China in the last three decades. We first present psychiatric studies from China with different research technologies, and then present a list of ongoing large-scale, open-access research cohorts and brain banks. Next, we look into transformations occurring in the healthcare system. Finally, we discuss the challenges to and potential opportunities for improving neuroscience research and clinical services in China. Understanding the progress and existing challenges will help to: (1) provide a basis for policy makers devising work plans that allocate resources to areas where the largest gaps remain and (2) facilitate collaborations among mental health professionals between China and the rest of the world.

Specific research topics

We begin with reviewing several aspects of research topics on psychiatric disorders, focusing on human research. The national and major cross-provincial epidemiological studies were retrieved from a reference search. For genetic and neuroimaging research, we systematically searched PubMed, Scopus and Chinese National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI) databases for reviews and meta-analyses that were conducted on Chinese populations from January 2000 to April 2021 (Fig. 2). Online Supplementary Tables S1 and S2 listed the included reviews and meta-analyses of genetic and neuroimaging studies. In addition, we discuss some representative studies published in recent years that were not covered by reviews and meta-analyses, as examples of research from China that contribute to the field knowledge.

Fig. 2. Reviews and meta-analyses on (a) genetic research and (b) neuroimaging research in China systematically retrieved from PubMed, Scopus and CNKI databases. The search terms were: [‘mental disorder’ OR psychiatr* OR schizophrenia OR ‘affective disorder’ OR depressi* OR ‘bipolar disorder’ OR ‘anxiety disorder’ OR autism OR ADHD OR ‘obsessive compulsive disorder’ OR ‘drug abuse’ OR ‘substance abuse’] AND [China[Title/Abstract]] AND [‘genetic’ OR ‘GWAS’ OR ‘methylation’ OR ‘gene expression’] for genetic research; [‘mental disorder’ OR psychiatr* OR schizophrenia OR ‘affective disorder’ OR depressi* OR ‘bipolar disorder’ OR ‘anxiety disorder’ OR autism OR ADHD OR ‘obsessive compulsive disorder’ OR ‘drug abuse’ OR ‘substance abuse’] AND [China[Title/Abstract]] AND [‘neuroimaging’ OR ‘brain imaging’ OR ‘magnetic resonance imaging’ OR MRI OR ‘positron emission tomography’ OR PET] for neuroimaging research. Limited to publication type: Meta-Analysis, Review and Systematic Review. Exclusion criteria include no-fulltext, not a journal article, not about genetic/neuroimaging research, not about psychiatric disorders or not conducted in Chinese populations.

Epidemiological studies

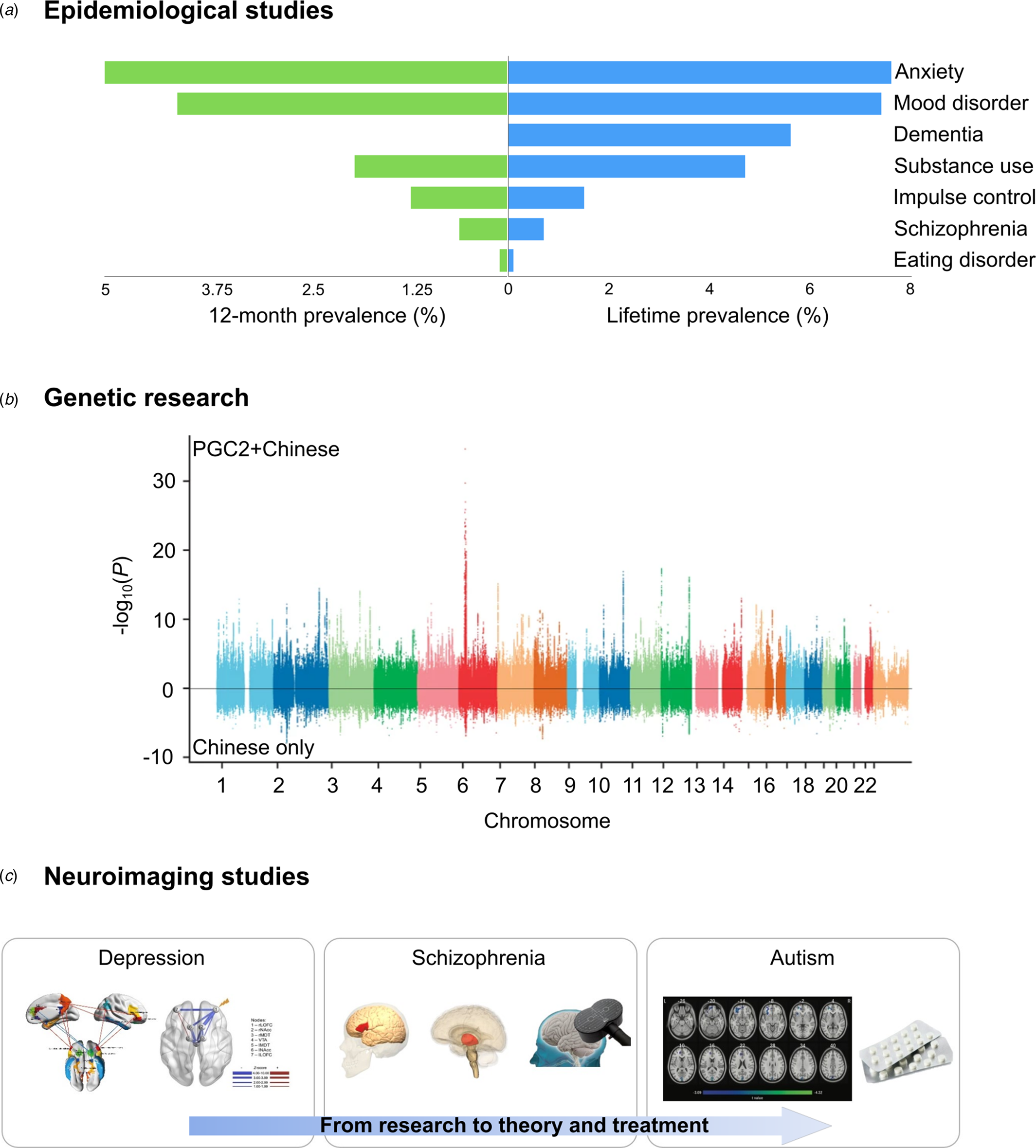

The China Mental Health Survey (CMHS) is the first nationally representative epidemiological survey of neuropsychiatric disorders and health services use (Huang et al., Reference Huang, Liu, Wang, Guan, Chen, Ma and Tan2016). According to this study, the prevalence of mental disorders in adulthood is 16.6% during the lifetime and 9.3% in the 12 months before the interview (Huang et al., Reference Huang, Wang, Wang, Liu, Yu, Yan and Wu2019b). The most prevalent psychiatric diagnosis was anxiety disorder, with a lifetime prevalence of 7.6% and a 12-month prevalence of 5.0% (Fig. 3a). The prevalence of mental disorders was slightly lower than that was reported in 2009, which found that the 1-month prevalence of any mental disorder was 17.5% (Phillips et al., Reference Phillips, Zhang, Shi, Song, Ding, Pang and Wang2009) and higher than an earlier epidemiological study conducted in Beijing and Shanghai with a 12-month prevalence of 7.0% (Shen et al., Reference Shen, Zhang, Huang, He, Liu, Cheng and Kessler2006). Despite disparities in the sampled population, diagnostic criteria, instruments used and assessed disorders between studies, the occurrence of mental disorders may have become more prevalent in China (Huang et al., Reference Huang, Wang, Wang, Liu, Yu, Yan and Wu2019b).

Fig. 3. Representative studies and research applications in psychiatric disorders. (a) Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of mental disorders in adulthood reported by Huang et al. (Reference Huang, Liu, Wang, Guan, Chen, Ma and Tan2016). (b) Genome-wide associations in the Chinese schizophrenia cases (lower) and in the combined sample (upper) of the Psychiatry Genomics Consortium (PGC2) and Chinese populations (43 175 cases; 65 166 controls) (Li et al., Reference Li, Wang, Zhang, Rolls, Yang, Palaniyappan and Feng2017a, Reference Li, Chen, Yu, He, Xu, Zhang and Shi2017b). (c) Implications to disease neuropathology and clinical application from neuroimaging studies of major depressive disorder (Cheng et al., Reference Cheng, Rolls, Qiu, Liu, Tang, Huang and Feng2016), schizophrenia (Du et al., Reference Du, Palaniyappan, Liu, Cheng, Gong, Zhu and Feng2021) and autism (Dai et al., Reference Dai, Zhang, Yu, Zhou, He, Ji and Li2021). Figures reproduced with permission.

Genetic research

In total, 201 records for genetic research were identified from PubMed, Scopus and CNKI databases. After duplication removal and screening for exclusion criteria, 49 reviews and meta-analyses were included (Fig. 2 and online Supplementary Table S1), among which 10 are reviews and 39 are meta-analyses of specific genetic variants and risk for psychiatric disorders in Chinese populations. Schizophrenia is the most commonly studied disease (25/49), followed by affective disorders (14/49), two autism spectrum disorders, two attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), one substance abuse, one suicide and four multiple disorders.

Findings from candidate gene associations and genome-wide association study (GWAS) in Chinese populations were summarized in three reviews (Collier & Li, Reference Collier and Li2003; Cui & Jiang, Reference Cui and Jiang2012; Yue, Yu, & Zhang, Reference Yue, Yu and Zhang2017). Among the 22 meta-analyses of candidate genes and schizophrenia, 10 reported significant associations between risk genes and schizophrenia in Chinese populations, seven reported no significant relationship while five indicated mixed results (online Supplementary Table S1). A recent Chinese GWAS for schizophrenia (7699 cases and 18 327 controls) identified seven genome-wide significant loci (Fig. 3b), and among the 108 loci identified from the Psychiatry Genomics Consortium (PGC2) cohort, 98 loci were overrepresented in Chinese cases (Li et al., Reference Li, Wang, Zhang, Rolls, Yang, Palaniyappan and Feng2017a, Reference Li, Chen, Yu, He, Xu, Zhang and Shib). A trans-ancestry meta-analysis of East Asian and European ancestries identified 208 significant associations in 176 genetic loci (53 novel) (Lam et al., Reference Lam, Chen, Li, Martin, Bryois, Ma and Huang2019). Pharmacogenomic studies from China identified five genome-wide significant loci, MEGF10, SLC1A1, PCDH7, CNTNAP5 and TNIK, that may contribute to individual therapeutic effects of antipsychotic treatment (Yu et al., Reference Yu, Yan, Wang, Li, Tan and Deng2018). Another study showed that rare damaging variants in glutamatergic neurotransmission are enriched in patients less responsive to antipsychotic treatment (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Man Wu, Yue, Yan, Zhang, Tan and Li2018).

For affective disorders, positive findings were reported in eight out of 11 meta-analyses of candidate genes and affective disorders (major depression and bipolar disorder), two reported negative results and one with mixed finding. Two reviews examined genetic variants and methylation in relation to affective disorders (Deng, Liu, He, Liu, & Zhang, Reference Deng, Liu, He, Liu and Zhang2008; Yang et al., Reference Yang, Jiao, Wang, Yang, Xiu, Qiao and Wang2014). Another review summarized findings of efficacies and toxicities of antidepressant drugs (Lu, Lu, Zhu, & Che, Reference Lu, Lu, Zhu and Che2015). For ADHD, a review implicated several candidate genes that may involve in the disease pathology, yet GWAS for ADHD in Chinese populations failed to identify any significant SNPs, and only found an increased burden of copy number variants in ADHD cases (Yang et al., Reference Yang, Neale, Liu, Lee, Wray, Ji and Wang2013a). For autism spectrum disorders, a study investigated de novo (DN) mutations in 189 risk genes in 1543 Chinese patients, and reported ~4% of patients carry a DN mutation in one of the 29 autism candidate genes (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Xu, Xu, Yu, Kong, Shen and Zhang2016a, Reference Wang, Guo, Xiong, Stessman, Wu, Coe and Eichlerb). In a follow-up study, the authors found that transmission of deleterious mutations is primarily associated with DN mutations (Guo et al., Reference Guo, Wang, Wu, Long, Coe, Li and Xia2018). Yang et al. (Reference Yang, Neale, Liu, Lee, Wray, Ji and Wang2013a, Reference Yang, Lu, Wang, Chen, Li, Cao and Gub) analysed two independent GWAS for alcohol consumption and found common variants at 12q24 that may contribute to drinking in Chinese Han population.

Genetic studies in Chinese populations can expand the ethnic diversity of neuroscience research findings. According to the GWAS catalogue, although European descent accounts for only 16% of the world's population, it represents approximately 79% of participants in GWAS (Martin et al., Reference Martin, Kanai, Kamatani, Okada, Neale and Daly2019). Therefore, research into non-European ethnic groups will inform common and unique genetic predispositions across populations.

Neuroimaging studies

In vivo neuroimaging techniques such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and positron emission tomography provided an unprecedented amount of information about macro-scale brain structure, function and metabolism. Application of neuroimaging techniques in psychiatric disorders has led to a better understanding of complex brain abnormalities in patients with psychiatric disorders, and facilitated psychoradiology as an emerging subspecialty of radiology (Gong, Kendrick, & Lu, Reference Gong, Kendrick and Lu2021; Gong, Lui, & Sweeney, Reference Gong, Lui and Sweeney2016; Huang, Gong, Sweeney, & Biswal, Reference Huang, Gong, Sweeney and Biswal2019a; Kressel, Reference Kressel2017; Lui et al., Reference Lui, Deng, Huang, Jiang, Ma, Chen and Gong2009; Lui, Zhou, Sweeney, & Gong, Reference Lui, Zhou, Sweeney and Gong2016; Port, Reference Port2018). We identified 13 neuroimaging reviews and meta-analyses of psychiatric disorders from PubMed, Scopus and CNKI databases that were conducted in Chinese populations (Fig. 2 and online Supplementary Table S2).

Among the 13 included reviews and meta-analyses, seven were about affective disorders. Many studies focused on functional connectivity abnormalities in patients with specific clinical characteristics (Smith, Reference Smith2015). For example, Tang et al. (Reference Tang, Lu, Zhang, Hu, Bu, Li and Huang2018a, Reference Tang, Wang, Hu, Dai, Xu, Yang and Xub) identified different patterns of amygdala-based functional connectivity from studies using adult and adolescent patients with major depressive disorder. Wang et al. (Reference Wang, Ma, Wu, Zhang, Guan, Ma and Lu2020a, Reference Wang, Gao, Tang, Lu, Zhang, Bu and Huangb) summarized large-scale brain network dysfunctions in the acute state and remitted state of bipolar disorder. Liu and Yao (Reference Liu and Yao2016) reviewed neuroimaging studies comparing patients with unipolar depression and bipolar disorder. Studies of first-episode, medication-naïve patients are particularly relevant to investigate primary neural abnormalities in disease pathology. For example, a study comparing first-episode, medication-naïve patients with current or remitted depression showed that both groups have abnormal activation in the ventromedial prefrontal cortex and precuneus during a stress task, whereas only remitted patients exhibited increased activations in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex and bilateral striatum (Ming et al., Reference Ming, Zhong, Zhang, Pu, Dong, Jiang and Rao2017). A follow-up study showed that both groups exhibited abnormalities in cortical morphology in the left precentral gyrus and left superior frontal gyrus (Xiong et al., Reference Xiong, Dong, Cheng, Jiang, Sun, He and Yao2019). These findings are in accordance with the psychoradiology hypothesis proposed by Gong et al., i.e. brain structural alterations lead to clinical symptoms through impacting on widely distributed functional connectivity (Canario, Chen, & Biswal, Reference Canario, Chen and Biswal2021; Schrantee, Ruhé, & Reneman, Reference Schrantee, Ruhé and Reneman2020).

Findings from neuroimaging studies may implicate potential target brain regions for treatment. For example, Cheng et al. (Reference Cheng, Rolls, Qiu, Liu, Tang, Huang and Feng2016) pinpointed dysconnectivity in two separable reward and non-reward neural circuits in patients with major depressive disorder using a brain-wide association study approach (Cheng et al., Reference Cheng, Palaniyappan, Li, Kendrick, Zhang, Luo and Feng2015). An independent study later showed that transcranial magnetic stimulation to the non-reward circuit achieved symptom remission in 59.5% of patients previously resistant to treatment (Feffer et al., Reference Feffer, Fettes, Giacobbe, Daskalakis, Blumberger and Downar2018) (Fig. 3c). Gong et al. (Reference Gong, Wu, Scarpazza, Lui, Jia, Marquand and Mechelli2011) differentiated patients with refractory and non-refractory depressive disorder based on grey and white matter volume, suggesting that brain deficits in distributed regions could predict the clinical outcome of depression.

For schizophrenia, two reviews summarized detailed lists of neuroimaging studies of schizophrenia in Chinese populations (Liu, Xu, & Jiang, Reference Liu, Xu and Jiang2014, Reference Liu, Cen, Jiang and Xu2018). Some recent studies showed that different functional dysconnectivity patterns exist in first-episode and chronic patients (Li et al., Reference Li, Wang, Zhang, Rolls, Yang, Palaniyappan and Feng2017a; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Zhang, Liu, Crow, Zhang, Palaniyappan and Li2019b). Dysconnectivity in the early stage of illness mainly involves the inferior frontal gyrus, which correlates with the polygenic risk score of language-related FOXP2 genes, supporting the notion that the genesis of schizophrenia is related to language-related anomalies (Crow, Reference Crow1997; Du et al., Reference Du, Palaniyappan, Liu, Cheng, Gong, Zhu and Feng2021) (Fig. 3c). Sun et al. (Reference Sun, Lui, Yao, Deng, Xiao, Zhang and Gong2015) found two subtypes of first-episode, medication-naive patients with schizophrenia using hierarchical clustering on diffusion tensor imaging data. Based on a unique sample of untreated schizophrenia with varying illness durations, Zhang et al. (Reference Zhang, Deng, Yao, Xiao, Li, Liu and Gong2015) showed accelerated age-related cortical thinning in the prefrontal and temporal areas in patients. Using machine learning techniques, Li et al. (Reference Li, Zalesky, Yue, Howes, Yan, Liu and Liu2020) developed a new hypothesis-driven neuroimaging biomarker for schizophrenia identification, prognosis and subtyping based on striatal functional abnormalities.

Another two reviews summarized neuroimaging abnormalities in patients with anxiety disorders (Chen & Shi, Reference Chen and Shi2011) and obsessive-compulsive disorder (Fan & Xiao, Reference Fan and Xiao2013). Neuroimaging studies also implicated the underlying neural circuitry of reinforcement-related processing in relation to alcohol abuse (Jia et al., Reference Jia, Ing, Quinlan, Tay, Luo, Francesca and Schumann2020, Reference Jia, Xie, Banaschewski, Barker, Bokde and Büchel2021), and implicated the therapeutic effect of bumetanide in reducing symptoms of children with autism spectrum disorder (Dai et al., Reference Dai, Zhang, Yu, Zhou, He, Ji and Li2021). Taken together, many neuroimaging studies from China investigated patients with specific clinical characteristics, aiming to disentangle complex neuropathology of psychiatric disorders and to provide potential target brain areas for treatment.

Research cohorts and brain banks

Large-scale, open-access imaging genetic cohorts

To identify reproducible and representative findings with small effect sizes, it is important to establish large-scale, multi-centre research cohorts (Button et al., Reference Button, Ioannidis, Mokrysz, Nosek, Flint, Robinson and Munafò2013; Poldrack et al., Reference Poldrack, Baker, Durnez, Gorgolewski, Matthews, Munafò and Yarkoni2017; Schnack & Kahn, Reference Schnack and Kahn2016). Several open-access cohorts with healthy participants have been established in China (Table 1). The Chinese Imaging Genetics (CHIMGEN) study is an imaging genetic study cohort which collected a full set of genomic, neuroimaging, environmental and behavioural data from 7000 healthy Chinese Han participants between 18 and 30 years old (Xu et al., Reference Xu, Guo, Cheng, Wang, Geng and Zhu2020). The Chinese Color Nest Project (CCNP) aims to delineate a normative trajectory of brain development across the lifespan (Yang, Kang, Li, Li, & Zhao, Reference Yang, Kang, Li, Li and Zhao2017a, Reference Yang, He, Zhang, Dong, Zhang, Zhu and Zuob). A neuroimaging data sharing platform – Brain Imaging Sharing Initiative (BISI, http://bisi.org.cn) was recently established, including repeated scans of healthy subjects (Liu et al., Reference Liu, Wei, Chen, Yang, Meng, Wu and Qiu2017; Zuo et al., Reference Zuo, Anderson, Bellec, Birn, Biswal, Blautzik and Milham2014) and healthy subjects with rumination states (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Chen, Shen, Li, Li, Lu and Yan2020).

Table 1. Large-scale, open-access research cohorts of healthy participants and patients with psychiatric disordersa

a Accessibility to the dataset is subjected to regulations on scientific data of China (http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/content/2018-04/02/content_5279272.htm) and individual cohort consortium.

Efforts to establish patient cohorts were also initiated (Table 1). One ongoing imaging genetic cohort is the Zhangjiang International Brain BioBank (ZIB) based at Fudan University. Participants in the ZIB constitute six cohorts, including patients with schizophrenia, major depressive disorder, autism spectrum disorder, stroke, neurodegenerative disorders and healthy university students. To date, 2143 subjects took part in the study and completed 1866 brain scans, 1491 blood samples, 2143 sets of behavioural questionnaires, 1143 sets of neurocognitive batteries and 619 gut microbiota samples. The ZIB aims to reach 12 000 participants by 2023, making it the world's largest Chinese population dataset for neuropsychiatric research. Another project, the REST-meta-MDD consortium collated resting-state functional MRI data from 1300 patients with major depressive disorder and 1128 healthy controls from 25 sites across China (Yan et al., Reference Yan, Chen, Li, Castellanos, Bai, Bo and Zang2019).

Brain banks

Brain banks are invaluable resources to investigate neurological and psychiatric disorders. Researchers can perform histological, genetic sequencing and molecular profiling studies based on postmortem brain tissues, yielding pathological information that is otherwise difficult to obtain (Kretzschmar, Reference Kretzschmar2009). There are hundreds of brain banks worldwide, including the BrainNet Europe (https://www.brainnet-europe.org), Australian Brain Bank Network (http://www.austbrainbank.org.au/index.html), US NIH NeuroBioBank (https://neurobiobank.nih.gov) and UK Brain Banks Network (https://brainbanknetwork.ac.uk/), etc. The China Brain Bank Consortium was set up in 2016, and released the Standardized Operational Protocol for brain tissue acquisition, processing and preservation (Qiu et al., Reference Qiu, Zhang, Bao, Zhu, Huang, Yan and Ma2019). Over the years, dozens of brain banks have been established in China (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Xia, Chen, Dai, Qiu, Meng and Chen2019a, Reference Wang, Zhang, Liu, Crow, Zhang, Palaniyappan and Lib, Reference Wang, Hao, Li and Yuc, Reference Wang, Shi, Xu, Fu, Zeng and Zhengd). Xiangya Hospital of Central South University started the first brain bank in China in 2004 (Cao et al., Reference Cao, Huang, Cai, Chan, Chen, Fan and Wang2020). Two national human brain banks, one in Zhejiang University collected about 200 human brain samples with healthy and neuropsychiatric disorders. The other national brain bank based in Peking Union Medical College has received 181 healthy samples, samples from 34 donors with dementia and 38 donors with other brain disorders by 2019 (Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Chen, Wang, Zhang, Yang, Zhang and Ma2018a, Reference Zhang, Li, Tang, Niznikiewicz, Shenton, Keshavan and Wangb). The Shanghai brain bank has collected about 50 postmortem brain samples in the past 3 years (Li et al., Reference Li, Xian, Po, Cao, Wu, Li and You2021).

Although initiation of large-scale research cohorts and brain banks started relatively late in China, they will constitute important platforms for neuroscience research in the near future. Datasets from China will facilitate international collaborations and increase both ethnic diversity and sample sizes of healthy participants and patients with varying kinds of brain disorders (Poo et al., Reference Poo, Du, Ip, Xiong, Xu and Tan2016).

Healthcare systems

Integrated hospital and community-based healthcare systems

Mental healthcare service is undergoing a transition from hospital-centred service mode to an integration of hospital and community-based service mode worldwide (Liang et al., Reference Liang, Mays and Hwang2018; Luo et al., Reference Luo, Law, Lin, Yao and Wang2017). Community-based treatment has been shown to reduce the number of relapses and chances of re-admission to hospitals (Luo et al., Reference Luo, Law, Wang, Shi, Zeng, Ma and Phillips2019). The community mental healthcare system in China is developed with the launch of a public health project, the ‘Central Government Support for the Local Management and Treatment of Severe Mental Illnesses’ in 2004. The project allocated 6.86 million Chinese yuan ($829 000 in 2004 US dollars) to nationwide mental health service centres for the management of patients with severe mental disorders, and was thus referred to as the ‘686 Project’ (Ma, Reference Ma2012). The amount of funding quickly reached 473.39 million yuan in 2014 (accumulated funding: 943.41 million yuan) (Liang et al., Reference Liang, Mays and Hwang2018). The goal of ‘686 Project’ was to provide free standardized antipsychotics and community-based follow-up visits to patients with severe mental disorders, as well as to build a team of specialists consisting of psychiatrists, nurses, psychologists and social workers to support patients and their families (Ma et al., Reference Ma, Liu, He, Xie, Xu, Hao and Yu2011). The ‘686 Project’ is a demonstration of a government-led, community-based integrated mental health service model in China.

With the implementation of the nationwide community-based healthcare system, a National Information System for Psychosis was established in 2011, to provide a reference for policy making and services delivering (Wu et al., Reference Wu, Ma, Zhang, Wang, Zhang, Guan and Wang2017). According to this system, there are 6 million patients with psychosis (0.43% of the population) registered to the system by the end of 2018. Among the registered patients, 81.30% were under medications, and 80.60% of patients were in stable stages. Mean untreated periods of schizophrenia, delusional psychosis, schizoaffective disorder and bipolar disorder were 3.54, 4.61, 2.73 and 3.18 years, respectively (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Ma, Wu, Zhang, Guan, Ma and Lu2020a, Reference Wang, Gao, Tang, Lu, Zhang, Bu and Huangb). The registration and management rate of psychosis patients have been increasing since 2014.

Early identification and prevention schemes

Another focus of mental healthcare is prevention and early treatment of psychiatric disorders (Beddington et al., Reference Beddington, Cooper, Field, Goswami, Huppert, Jenkins and Thomas2008). For psychosis, many studies investigated neural and cognitive deficits in subjects with subclinical psychotic symptoms or with familial risk for psychosis (Cannon et al., Reference Cannon, Yu, Addington, Bearden, Cadenhead, Cornblatt and Kattan2016; Cornblatt et al., Reference Cornblatt, Lencz, Smith, Correll, Auther and Nakayama2003; Fusar-Poli et al., Reference Fusar-Poli, Borgwardt, Bechdolf, Addington, Riecher-Rössler, Schultze-Lutter and Yung2013) to identify early pathological changes and targets for prediction and intervention (Addington et al., Reference Addington, Liu, Buchy, Cadenhead, Cannon, Cornblatt and McGlashan2015; Simon et al., Reference Simon, Cattapan-Ludewig, Zmilacher, Arbach, Gruber, Dvorsky and Umbricht2007). The Shanghai Mental Health Center launched the Shanghai At Risk for Psychosis (SHARP) programme, which recruited 517 individuals at clinical high risk for psychosis (Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Tang, Li, Woodberry, Kline, Xu and Wang2020a, Reference Zhang, Xu, Tang, Wei, Hu, Hu and Wangb). The authors showed that 24% of high-risk individuals converted to psychosis in 2 years (Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Xu, Li, Woodberry, Kline, Jiang and Wang2021), with a higher conversion rate in a subgroup of high-risk individuals with extensive negative symptoms and cognitive deficits (Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Tang, Li, Woodberry, Kline, Xu and Wang2020a, Reference Zhang, Xu, Tang, Wei, Hu, Hu and Wangb). Individual risk for transition to psychosis can be predicted using clinical symptoms and cognitive functioning scores with good discriminative power (area under the curve of ROC = 0.78) (Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Chen, Wang, Zhang, Yang, Zhang and Ma2018a, Reference Zhang, Li, Tang, Niznikiewicz, Shenton, Keshavan and Wangb, Reference Zhang, Xu, Li, Woodberry, Kline, Jiang and Wang2021).

Strengths and challenges for mental health research and services

Growing funding investment and interdisciplinary research centres

Brain science and brain-inspired technology have been raised to the national strategic level in the 13th Five-Year Plan for Science and Innovation (The State Council, 2016). The increasing rate of gross domestic spending on research and development (R&D) in China is quickly catching up with the USA (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, 2020). During 2011–2015, the National Key Basic Research Program of China (973 Program) funded 50 neuroscience projects, amounting to one billion Chinese yuan (approximately 0.15 billion US dollars) (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Xu, Xu, Yu, Kong, Shen and Zhang2016a, Reference Wang, Guo, Xiong, Stessman, Wu, Coe and Eichlerb). To promote research translation and application to clinical services, China has set up 50 National Clinical Research Centres as collaborative research networks between hospitals, research institutes and universities since 2013 (Ministry of Science and Technology, 2013). Three National Clinical Research Centres for mental disorders were founded.

International collaborations

Investment in research funding can drive an increase in the number of publications, yet the impact of research is more closely related to the extent of international cooperation (Wagner & Jonkers, Reference Wagner and Jonkers2017). The current outbreak of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) demonstrates the vital importance of sharing scientific information and initiating concerted plans across countries to combat the pandemic (Rourke, Eccleston-Turner, Phelan, & Gostin, Reference Rourke, Eccleston-Turner, Phelan and Gostin2020), including its effects on mental health (Vatansever, Wang, & Sahakian, Reference Vatansever, Wang and Sahakian2021). Research collaborations in China are growing at a rapid speed: the number of international co-authorship publications rose from 16 000 in 2006 to 71 000 in 2015 (Zhou et al., Reference Zhou, Ren, Zhang, Yue, Wu, Nan and Yang2019). The National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC), the main governmental funding agency, funded 1140 International (Regional) Cooperation and Exchange Programs in 2019, amounting to 1 billion Chinese yuan (0.15 billion US dollars) (Tian et al., Reference Tian, Zhang, Yin, Guo, Wang and Yang2020). International collaborations on research and clinical services are both active; for example, the Institute of Science and Technology for Brain-inspired Intelligence (ISTBI) of Fudan University established long-term collaborations with research teams from the University of Cambridge, the University of Oxford, King's College London and the University of Sydney. The Shanghai Institute of Mental Health formed partnerships with leading psychiatric hospitals such as the Massachusetts General Hospital and the Maudsley Hospital to collaborate on research and training projects (Barako, Li, & Yeung, Reference Barako, Li and Yeung2019). Among the top 10 research institutes in China, international collaborations account for 30–45% of all research output (Springer Nature, 2020).

Insights from traditional Chinese medicine

Traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) is an integral part of healthcare system in China. According to the National Bureau of Statistics, China has 4221 TCM hospitals in 2019, consisting of 12.3% of the medical service capacity (National Bureau of Statistics, 2019). Consultation to TCM is high among patients with mental disorders, because of its general acceptance, low stigmatization, perceived low costs and less side effects (Thirthalli et al., Reference Thirthalli, Zhou, Kumar, Gao, Vaid, Liu and Nichter2016). TCM has different forms including herbal medicine, acupuncture, moxibustion and qigong, etc. The therapeutic effect often relies on polypharmacological interactions of the ingredients and the philosophy of taking mind and body as a whole. Based on previous reviews and meta-analyses (Thirthalli et al., Reference Thirthalli, Zhou, Kumar, Gao, Vaid, Liu and Nichter2016; Ulett, Han, & Han, Reference Ulett, Han and Han1998; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Xia, Chen, Dai, Qiu, Meng and Chen2019a, Reference Wang, Zhang, Liu, Crow, Zhang, Palaniyappan and Lib, Reference Wang, Hao, Li and Yuc, Reference Wang, Shi, Xu, Fu, Zeng and Zhengd), studies showed promising effects of TCM, such as acupuncture and Chinese herbs, in alleviating psychiatric symptoms, although high-quality studies are needed to confirm the conclusion. The potential efficacy of TCM can be understood by analysing bioactive compounds of herbal medicines. For example, a study analysed 15 herbal medicines targeting neurodegenerative disorders and found a large overlap of chemical compounds between herbal medicines and standard treatment of neurodegenerative disorders (Tang, Ye, Feng, & Quinn, Reference Tang, Ye, Feng and Quinn2016). The discovery of artemisinin extracted from Chinese medicine to treat malaria is a good example that investigation into TCM with known efficacy may be a promising strategy to develop novel treatment against mental disorders (Tu, Reference Tu2016).

Promoting research quality and open science

Although China has been the second most prolific country in yearly neuroscience publications (Fig. 1c), Chinese researchers still face the challenge to promote research quality and increase the level of transparency. The growth of high-impact publications is slower than the rise of overall publication numbers (Leydesdorff, Wagner, & Bornmann, Reference Leydesdorff, Wagner and Bornmann2014). The quality of randomized controlled trials is also of concern in clinical studies, especially those published in domestic journals (Tong, Li, Ogawa, Watanabe, & Furukawa, Reference Tong, Li, Ogawa, Watanabe and Furukawa2018). In order to respond to these challenges, the government has been reforming the academic evaluation system that placed much emphasis on the number of publications (Qiu, Reference Qiu2010), and has announced strict regulations against academic fraud (Normile, Reference Normile2017). Meanwhile, to promote open research, China initiated the construction of national data sharing platforms since 2001 (Chen & Li, Reference Chen and Li2020), and established 20 National Scientific Data Centres and 30 Biological Materials Resource Banks by 2019 (Ministry of Science and Technology, 2019). If effectively implemented, these measures and resources will improve research quality in China over the long term.

More equitable distribution of healthcare resources

Although mental healthcare expenditure in underdeveloped areas is increasing every year since the implementation of the ‘686 Project’, there is still a large disparity in terms of medical resources between urban and rural areas (Liang et al., Reference Liang, Mays and Hwang2018). Highly trained professionals and financial support are heavily centred in Southeast provincial hospitals, whereas township and rural area clinics – the primary healthcare system, often lack professionals and facilities to provide high-quality medical services.

Another challenge is insufficient research and clinics for specific subgroups of population. For example, due to rapid urbanization and internal migration, China has approximately 68.8 million left-behind children, and 54.9 million are in rural areas (Duan, Lai, & Qin, Reference Duan, Lai and Qin2017). Left-behind children have a higher risk for emotional and behavioural difficulties and are more likely to encounter school bullying (Fellmeth et al., Reference Fellmeth, Rose-Clarke, Zhao, Busert, Zheng, Massazza and Devakumar2018; Tang et al., Reference Tang, Lu, Zhang, Hu, Bu, Li and Huang2018a, Reference Tang, Wang, Hu, Dai, Xu, Yang and Xub). Another group of people in need of more healthcare resources is China's 55 ethnic minorities, constituting 8.5% of the national population. Many minority groups live in traditional rural areas where healthcare services are insufficient. They are also vulnerable to the adverse effects of rapid social and economic changes (Yang et al., Reference Yang, Kang, Li, Li and Zhao2017a, Reference Yang, He, Zhang, Dong, Zhang, Zhu and Zuob).

Reducing stigma and raising public awareness of mental disorders

Stigmatization and discrimination against mental disorders are common impediments that prevent individuals seeking help from professionals (Patel et al., Reference Patel, Xiao, Chen, Hanna, Jotheeswaran, Luo and Saxena2016). This may be particularly prominent in China, as the collectivism culture may aggravate the self-stigmatization of patients and their family members (Yang & Kleinman, Reference Yang and Kleinman2008). The consultation rate in the Psychiatry Department is low in China. An early epidemiological study conducted in Beijing and Shanghai from 2001 to 2002 reported that only 3.4% of psychiatric patients sought treatment in the previous 12 months (Shen et al., Reference Shen, Zhang, Huang, He, Liu, Cheng and Kessler2006). In another study performed during 2001–2005, 8% of patients with mental disorders ever sought professional help, and only 5% had ever seen a mental health care professional (Phillips et al., Reference Phillips, Zhang, Shi, Song, Ding, Pang and Wang2009). Delayed treatment could result in prolonged illness and worse prognosis, as indicated by studies examining the effects of the duration of untreated psychosis (Allott et al., Reference Allott, Fraguas, Bartholomeusz, Díaz-Caneja, Wannan, Parrish and Rapado-Castro2018; Marshall et al., Reference Marshall, Lewis, Lockwood, Drake, Jones and Croudace2005).

Mental health literacy is defined as ‘knowledge and beliefs about mental disorders which aid their recognition, management or prevention’ (Jorm, Reference Jorm2000). Better mental health literacy can increase the rate of detection and treatment of psychiatric disorders and promote help-seeking behaviours. A study showed that compared with Australian people, Chinese people (sampled from Shanghai, Hong Kong, Taiwan and Australia) generally had a lower level of recognition of depression (12.1–24.4% v. 73.9%) and early schizophrenia (6.0–21.2% v. 37.90%) (Wong et al., Reference Wong, Cheng, Zhuang, Ng, Pan, He and Poon2017). To increase mental health literacy and reduce stigmatization against psychiatric disorders, more efforts should be spent on educational campaigns and psychological interventions for the general public and patients with mental disorders (Xu, Huang, Kösters, & Rüsch, Reference Xu, Huang, Kösters and Rüsch2017; Xu, Rüsch, Huang, & Kösters, Reference Xu, Rüsch, Huang and Kösters2017).

Conclusions

In summary, significant progress has been made in research and healthcare for psychiatric disorders in China. Specifically, a nationwide epidemiological survey suggested a lifetime prevalence of 16.6% for mental disorders. Genetic and neuroimaging studies in Chinese populations expanded the ethnic diversity of neuroscience research and elucidate neuropathological changes in patients with specific clinical characteristics. Ongoing efforts are devoted to establish large-scale research cohorts and brain banks in Chinese populations. Regarding clinical services, community-based healthcare is being integrated into hospital-centred healthcare systems to provide continuous support to patients. Early prevention and intervention is a new focus in mental healthcare. These achievements in research and clinical services are indispensable to growing funding investment and continued engagement in international collaborations. Knowledge from TCM may provide insights into drug development for psychiatric disorders. Meanwhile, we acknowledge existing challenges such as efforts are still needed to improve research quality and to equally distribute healthcare resources. With ongoing efforts, we expect to see continued improvement in research and clinical services for psychiatric disorders. These achievements will contribute to global efforts to understand the neurobiological basis of psychiatric disorders and to devise novel, more effective treatments, so that all individuals can reach their potentials and flourish in society.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291721002816.

Acknowledgements

Professor J. Feng is supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (No.2019YFA0709502), 111 Project (No.B18015), Shanghai Municipal Science and Technology Major Project (No.2018SHZDZX01), ZJLab and Shanghai Center for Brain Science and Brain-Inspired Technology. X. Chang is sponsored by Shanghai Sailing Program (No. 21YF1402400). Professor Q. Gong is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation (Grant Nos. 81621003 and 82027808). Data about the Zhangjiang International Brain BioBank (ZIB) is from the ZIB Consortium. We would like to thank Professor Barbara Sahakian for her constructive advice on the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

None.