Introduction

Deaths of despair (i.e. deaths from suicide, drug overdose, and alcohol-related liver disease; Case & Deaton, Reference Case and Deaton2017) are rising among working-age adults in the U.S. (Case & Deaton, Reference Case and Deaton2015; National Academies of Sciences, 2021; Shiels et al., Reference Shiels, Tatalovich, Chen, Haozous, Hartge, Nápoles and Freedman2020; Woolf & Schoomaker, Reference Woolf and Schoomaker2019) and possibly other countries as well (Allik, Brown, Dundas, & Leyland, Reference Allik, Brown, Dundas and Leyland2020; Augarde, Gunnell, Mars, & Hickman, Reference Augarde, Gunnell, Mars and Hickman2022; Brown, Allik, Dundas, & Leyland, Reference Brown, Allik, Dundas and Leyland2019; Probst & Rehm, Reference Probst and Rehm2018; Walsh et al., Reference Walsh, McCartney, Minton, Parkinson, Shipton and Whyte2021). In the U.S., these increases are commonly conflated with the opioid epidemic and its concomitant misprescription of opioids (National Academies of Sciences, 2021; Szalavitz, Reference Szalavitz2021). However, deaths of despair and related maladies (e.g. suicidality, substance misuse) can proliferate anywhere, given certain societal conditions (e.g. inequality, political and economic shifts, lack of communal support; Blakely, Tobias, & Atkinson, Reference Blakely, Tobias and Atkinson2008; Brainerd, Reference Brainerd2021; King, Scheiring, & Nosrati, Reference King, Scheiring and Nosrati2022; Sterling & Platt, Reference Sterling and Platt2022). Moreover, relatively few studies have examined despair-related maladies outside of the U.S. context. Here, we adopt a lifespan developmental approach to examine the characteristics of midlife adults afflicted by a syndrome of despair-related maladies. In a population-representative cohort of New Zealanders who have been followed from birth to midlife, we tested: (1) a hypothesized model of a multi-faceted despair syndrome at midlife, encompassing not only suicidality and substance misuse, but also sleep problems and pain; and (2) the hypothesis that adults with a more severe despair syndrome at midlife tended to have had psychopathology in adolescence.

The hypothesis that there is a multi-faceted midlife despair syndrome consisting of a constellation of maladies (i.e. suicidality, substance misuse, sleep problems, and pain) is based on evidence that these maladies rarely exist in isolation (Driscoll, Edwards, Becker, Kaptchuk, & Kerns, Reference Driscoll, Edwards, Becker, Kaptchuk and Kerns2021; Oquendo & Volkow, Reference Oquendo and Volkow2018; Turecki et al., Reference Turecki, Brent, Gunnell, O'Connor, Oquendo, Pirkis and Stanley2019). Although the contributions of suicidality and substance misuse to deaths of despair are clear and well recognized, two additional maladies that are born out of the life experiences of despair-afflicted adults are sleep problems and musculoskeletal pain (Case & Deaton, Reference Case and Deaton2021; Case, Deaton, & Stone, Reference Case, Deaton and Stone2020; Drake, Roehrs, Richardson, Walsh, & Roth, Reference Drake, Roehrs, Richardson, Walsh and Roth2004; Hartvigsen et al., Reference Hartvigsen, Hancock, Kongsted, Louw, Ferreira, Genevay and Woolf2018). Lower educational attainment (i.e. not having a bachelor's degree) appears to be the strongest demographic predictor of deaths of despair (Case & Deaton, Reference Case and Deaton2021). Individuals without a bachelor's degree are more likely to hold jobs characterized by difficult working conditions that can directly cause sleep problems and pain (Drake et al., Reference Drake, Roehrs, Richardson, Walsh and Roth2004; Matre et al., Reference Matre, Christensen, Mork, Ferreira, Sand and Nilsen2021). Indeed, media accounts of deaths of despair portray lives in which deaths from illicit substance use followed from medications initially prescribed to treat the sleep problems and pain that arose from difficult working conditions (e.g. night or shift work, heavy physical labor).

Suicidality, substance misuse, sleep problems, and pain not only frequently co-occur; they also exacerbate one another. For example, individuals may be prescribed sedatives and opioids to address sleep problems and pain, which in turn increases their risk for substance misuse (Koffel, DeRonne, & Hawkins, Reference Koffel, DeRonne and Hawkins2020). Similarly, substance misuse is one of the strongest risk factors for suicide (Lynch et al., Reference Lynch, Peterson, Lu, Hu, Rossom, Waitzfelder and Ahmedani2020). Moreover, since sleep problems and musculoskeletal pain indicate the presence of psychic and physical suffering that individuals often seek to quiet or end, it seems reasonable that these maladies might exist as part of a syndrome that can be identified before an individual succumbs to a death of despair. Taken together, extant research suggests the existence of a multi-faceted despair syndrome; it also implies that examining despair-related maladies individually provides a limited perspective that underestimates individuals' true risk for dying a death of despair. Yet previous research tends to study these maladies in isolation, and in clinical practice they are commonly treated individually in separate clinics.

Since midlife despair is postulated to form a syndrome of interconnected maladies, it stands to reason that this syndrome has an antecedent in early life. In pursuit of this antecedent, we propose that psychopathology in adolescence represents a promising candidate factor for several reasons. First, the onset of psychopathology is most likely to occur during adolescence (Kessler et al., Reference Kessler, Berglund, Demler, Jin, Merikangas and Walters2005; Moffitt & Caspi, Reference Moffitt and Caspi2019; Polanczyk, Salum, Sugaya, Caye, & Rohde, Reference Polanczyk, Salum, Sugaya, Caye and Rohde2015). Second, psychopathology in adolescence disrupts the transition from school to work life (Bardone, Moffitt, Caspi, Dickson, & Silva, Reference Bardone, Moffitt, Caspi, Dickson and Silva1996; Hale, Bevilacqua, & Viner, Reference Hale, Bevilacqua and Viner2015; Veldman et al., Reference Veldman, Bültmann, Stewart, Ormel, Verhulst and Reijneveld2014) and, third, predicts poor aging-related outcomes (Bourassa et al., Reference Bourassa, Moffitt, Ambler, Hariri, Harrington, Houts and Caspi2022). We hypothesized that adolescent psychopathology could be a starting point for a syndrome of despair-related maladies because it is known to disrupt educational attainment, limiting individuals' employment opportunities and making them more likely to have jobs characterized by difficult working conditions. Finally, psychopathology in adolescence is treatable and thus amenable to prevention efforts (Deković et al., Reference Deković, Slagt, Asscher, Boendermaker, Eichelsheim and Prinzie2011; Lee, Horvath, & Hunsley, Reference Lee, Horvath and Hunsley2013; Swan et al., Reference Swan, Kendall, Olino, Ginsburg, Keeton, Compton and Albano2018). Identifying a modifiable risk factor for a syndrome of midlife despair would allow prevention and intervention strategies to focus on vulnerable populations early in development to prevent later deaths of despair. However, despite the need to understand developmental pathways to despair (Shanahan & Copeland, Reference Shanahan and Copeland2021), previous research has not yet examined whether adolescent psychopathology precedes a syndrome of despair-related maladies in midlife, a time in the lifecourse during which deaths of despair were first identified (Case & Deaton, Reference Case and Deaton2015) and during which mortality rates have been rising most steeply for decades (Case & Deaton, Reference Case and Deaton2017; National Academies of Sciences, 2021; Tilstra, Simon, & Masters, Reference Tilstra, Simon and Masters2021). Converging evidence across high-income nations suggests that despair-related maladies may peak during midlife (Case et al., Reference Case, Deaton and Stone2020; Giuntella et al., Reference Giuntella, McManus, Mujcic, Oswald, Powdthavee and Tohamy2022).

The present study fills three major gaps. First, we examine associations between individual-level characteristics and a midlife despair syndrome, in contrast with previous research that has focused on trends at the population level. Second, we adopt a lifespan developmental perspective for studying midlife despair-related maladies, looking back several decades in individuals' lives, in contrast with previous research that has provided point-in-time descriptions of rates of despair-related maladies and deaths. A developmental perspective is needed because knowledge about individuals' personal histories can help inform prevention strategies. Finally, we take a comprehensive and cross-domain approach to measuring a midlife despair syndrome, in contrast with previous research that has examined despair-related maladies individually (Copeland et al., Reference Copeland, Gaydosh, Hill, Godwin, Harris, Costello and Shanahan2020).

The present study is well suited to examine adolescent psychopathology as an antecedent of a midlife despair syndrome due to its prospective longitudinal design and multi-modal (i.e. self-report, informant-report, and national register data) assessment of midlife despair-related maladies. We used confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) to test our hypothesized model of a midlife despair syndrome using 12 indicators measured when participants were 45 years old. We tested the construct validity of the midlife despair syndrome by examining associations with putatively related external constructs, including lower educational attainment, difficult working conditions, social disconnection, diminished wellbeing, and pessimism about the future. We then tested whether adults with more despair-related maladies at midlife tended to have had a mental disorder [i.e. depression, an anxiety disorder, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), or conduct disorder] in adolescence. Because sex, childhood socioeconomic status (SES), and childhood IQ are known risk factors for individual despair-related maladies (Bartley & Fillingim, Reference Bartley and Fillingim2013; McHugh, Votaw, Sugarman, & Greenfield, Reference McHugh, Votaw, Sugarman and Greenfield2018; McLean et al., Reference McLean, Gunn, Wyke, Guthrie, Watt, Blane and Mercer2014; Nock et al., Reference Nock, Borges, Bromet, Cha, Kessler and Lee2008; Turecki et al., Reference Turecki, Brent, Gunnell, O'Connor, Oquendo, Pirkis and Stanley2019), we accounted for these potential confounding factors in our analyses. Additionally, we tested whether adults who had more despair-related maladies at midlife had more comorbid mental disorders in adolescence. Finally, although the term ‘despair’ implies that depression is the most relevant mental disorder for deaths of despair, we tested associations for each adolescent mental disorder individually to ascertain the generality v. specificity of associations.

Methods

Sample

Participants were members of the Dunedin Longitudinal Study, a representative birth cohort (N = 1037; 91% of eligible births; 51.6% male) born between April 1972 and March 1973 in Dunedin, New Zealand, who were eligible based on residence in the province and who participated in the first assessment at age 3 (Poulton, Moffitt, & Silva, Reference Poulton, Moffitt and Silva2015). The cohort represented the full range of SES in the general population of New Zealand's South Island and, in adulthood, matched the NZ National Health & Nutrition Survey on key health indicators (BMI, smoking, physical activity, doctor visits; Poulton et al., Reference Poulton, Moffitt and Silva2015) and the NZ Census on educational attainment (Richmond-Rakerd et al., Reference Richmond-Rakerd, D'Souza, Andersen, Hogan, Houts, Poulton and Moffitt2020). The cohort consists primarily of White participants (93%), matching South Island demographics (Poulton et al., Reference Poulton, Moffitt and Silva2015). Assessments were carried out at birth and ages 3, 5, 7, 9, 11, 13, 15, 18, 21, 26, 32, 38, and, most recently (completed April 2019), 45 years. Overall, of the original 1037 cohort participants, 997 were still alive at age 45; of these, 938 (94.1%) participated in the age-45 assessments [474 men (50.5%)]. Participants assessed at age 45 did not differ significantly from other living participants in terms of childhood SES, childhood IQ, or history of psychopathology (online Supplementary eAppendix 1). Based on these analyses, data were assumed to be missing at random. Of the 938 who participated at age 45, 926 had sufficient data across indicators of despair-related maladies for inclusion in analyses (i.e. at least 50% of data points present within each indicator or subfactor).

The Dunedin Study was approved by the NZ-HDEC (Health and Disability Ethics Committee). The study protocol was approved by the institutional ethical review boards of the participating universities. Study members gave written informed consent before participating in each assessment.

Assessment of adolescent psychopathology

Mental disorders [i.e. depression, an anxiety disorder, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), and conduct disorder] were assessed at ages 11, 13, and 15 (Table 1). Since adolescence is generally understood to be the transition phase between childhood and adulthood (World Health Organization, 2023), we considered ages 11 to 15 to represent adolescence in this sample. Age 18 was not included because students in New Zealand are able to leave school at age 15; thus, some participants were already in the labor force and living independently by age 18. Prevalence of psychopathology (Caspi et al., Reference Caspi, Houts, Belsky, Goldman-Mellor, Harrington, Israel and Moffitt2014) was comparable to that in U.S. epidemiological samples (Merikangas et al., Reference Merikangas, He, Burstein, Swanson, Avenevoli, Cui and Swendsen2010).

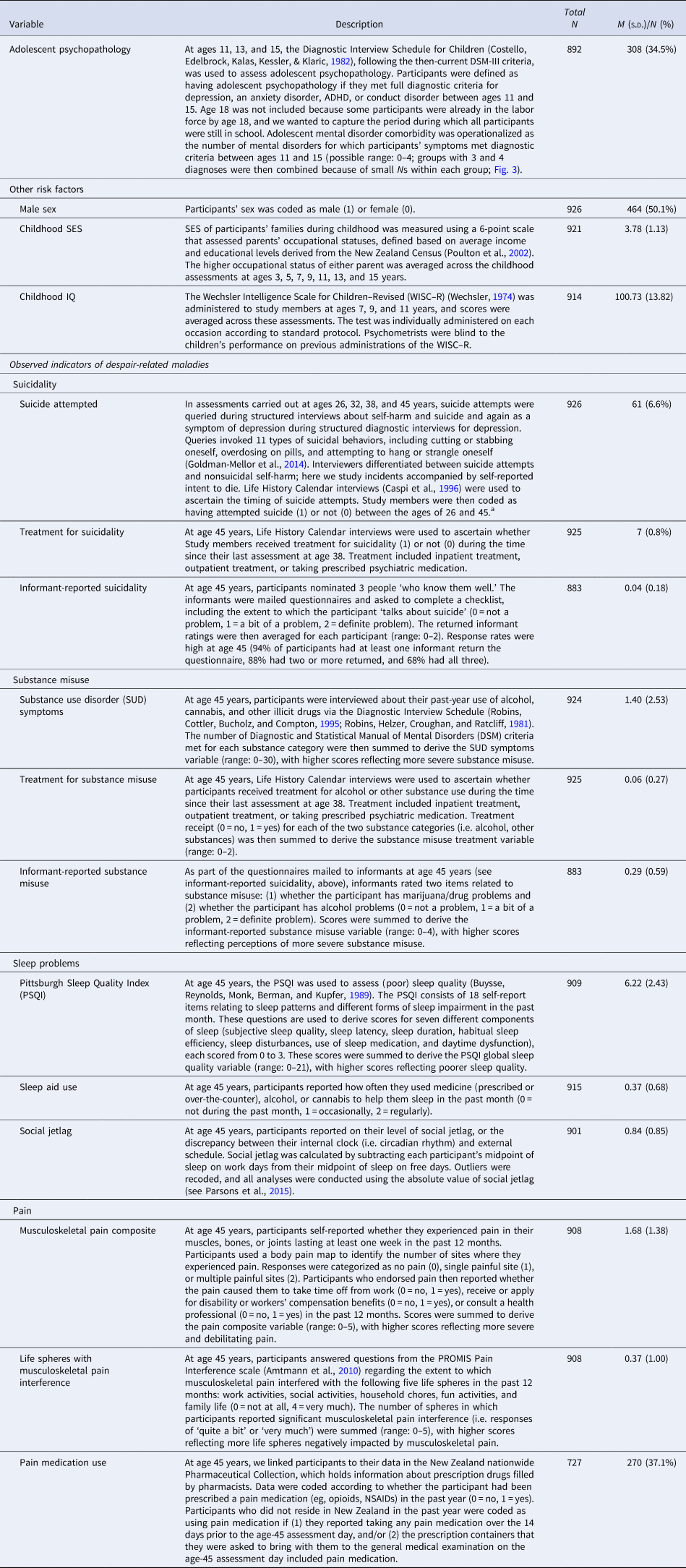

Table 1. Descriptions and descriptive statistics for adolescent psychopathology, other risk factors, and observed indicators of midlife despair-related maladies

Note. Total N refers to the number of participants for whom data was available for each variable, whereas N in the farthest right column refers to the number of participants who had a score of ‘1’ for each dichotomous variable.

a Suicidal ideation was assessed within the depression interview, only if a participant endorsed at least one of the two gate items (i.e. depressed mood, anhedonia); therefore, suicidal ideation data were not available for a large portion of the sample and were not used in analyses.

Measuring other potential risk factors

We selected other potential risk factors as covariates in regression models based on theory and documented associations with adolescent psychopathology and with suicidality, substance misuse, sleep problems, and pain: sex, childhood SES, and childhood IQ (Table 1).

Measuring indicators of midlife despair-related maladies

We assessed 12 indicators of despair-related maladies at age 45 in four domains: suicidality, substance misuse, sleep problems, and pain (Table 1). Indicators were derived from a variety of modalities, including self-report (e.g. sleep quality), informant-report (e.g. perceived misuse of alcohol and drugs), and national register data (e.g. pain medication use). These indicators were used as observed variables in the CFA models. Although we could have included additional variables in the models, we restricted the models to the variables and domains listed in Table 1 for conceptual reasons. First, based on previous research, it is not clear that other constructs (i.e. depression) are truly part of the midlife despair syndrome. Instead, depression is typically conceptualized as an antecedent or cause of despair-related maladies (Copeland et al., Reference Copeland, Gaydosh, Hill, Godwin, Harris, Costello and Shanahan2020). Second, to avoid overlap between the midlife despair syndrome and adolescent psychopathology, we did not include depression and anxiety in the CFA models. However, validation analyses tested associations between the midlife despair syndrome and potentially related constructs at midlife (online Supplementary eAppendix 3).

Statistical analysis

We used CFA to model the structure of midlife despair-related maladies. CFAs were performed using the weighted least squares means and variance adjusted (WLSMV) algorithm and 1000 bootstrapped samples in Mplus (version 8.7; Muthén and Muthén, Reference Muthén and Muthén1998–2017). The WLSMV estimator is appropriate for categorical and nonmultivariate normal data and provides consistent estimates when data are missing at random with respect to covariates (Asparouhov & Muthén, Reference Asparouhov and Muthén2010). The following variables were treated as categorical in analyses: suicide attempted, suicidality treatment, substance misuse treatment, sleep aid use, and pain medication use (see online Supplementary eAppendix 2 for more information regarding CFA). We then extracted the factor scores derived from CFA that represented the despair syndrome as a whole, as well as each of its constituent elements (i.e. suicidality, substance misuse, sleep problems, and pain), for use in further regression analyses.

To achieve our aim of ‘looking back’ into the developmental histories of participants afflicted with despair-related maladies, we conducted a series of regression analyses using adolescent psychopathology variables as predictor (independent) variables and midlife despair variables as outcome (dependent) variables. First, we performed ordinary least squares (OLS) regression to test whether adolescent psychopathology predicted the despair syndrome (i.e. the general despair factor derived from CFA) at midlife. To test whether sex, childhood SES, or childhood IQ could explain this association, we then adjusted for these risk factors. We also performed OLS regression to test whether the number of mental disorders diagnosed in adolescence predicted the midlife despair syndrome. Finally, we performed OLS regression to test whether specific adolescent disorders predicted the midlife despair syndrome.

The premise and analysis plan for this project were preregistered at https://dunedinstudy.otago.ac.nz/files/1652150270_Brennan_Concept%20Paper_Diseases%20of%20Despair_2-21-22.pdf. Results reported here were checked for reproducibility by an independent data analyst, who recreated the code by working from the manuscript and applying it to a fresh copy of the dataset.

Results

A measurement model of despair-related maladies at midlife

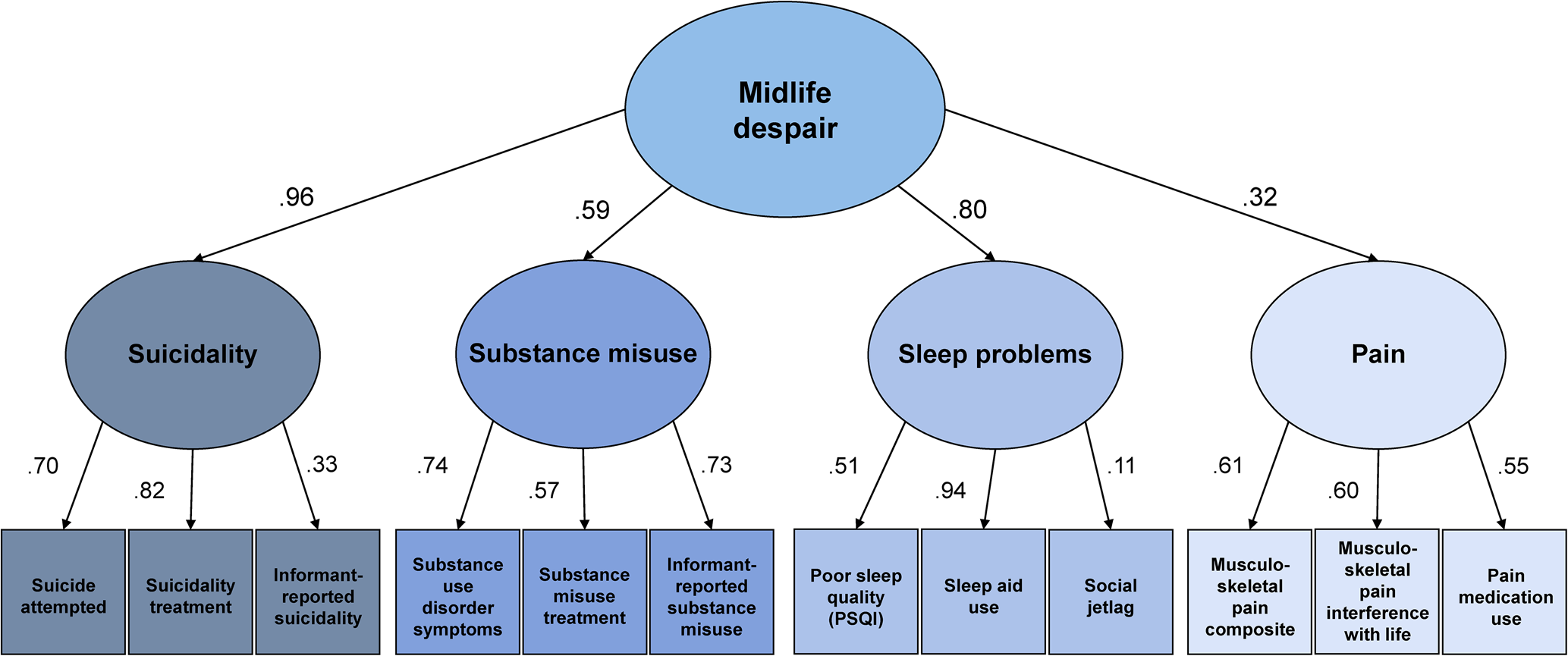

CFA indicated that the higher-order factor model (Fig. 1) fit the data closely: CFI = 0.96, TLI = 0.95, RMSEA = 0.04, 90% CI [0.03–0.05], SRMR = 0.07 (online Supplementary eTable 1). Loadings for the suicidality, substance misuse, sleep problems, and pain subfactors on the general midlife despair factor were all significant and positive, ranging from moderate (0.32 for pain) to strong (0.96 for suicidality). Loadings for all of the indicators on their respective subfactors were significant and positive, ranging from relatively weak (0.11 for social jetlag) to strong (0.94 for sleep aid use; see online Supplementary eTable 2 for correlations between the observed indicators of midlife despair-related maladies).

Fig. 1. The structure of midlife despair-related maladies.

Note: Ovals are latent (unobserved) factors representing a syndrome of midlife despair and its constituent elements; boxes are observed indicators of each constituent element. Numbers are standardized factor loadings.

Validation of the general despair factor

The general midlife despair factor is hypothesized to reflect an underlying sense of despair; hopelessness about one's own future; social disconnection; and a lack of opportunity, both real and perceived. Analyses were performed to test the construct validity of the general midlife despair factor (see online Supplementary eAppendix 3 for full results). Consistent with expectations, participants with higher scores on the general midlife despair factor reported lower levels of satisfaction with their lives (r = −0.38, p < 0.001), greater pessimism toward growing older (t = 4.70, p < 0.001), and poorer self-rated health (r = −0.28, p < 0.001). They were less likely to believe they would live to age 75 (t = 6.20, p < 0.001). They were more likely to have experienced depression within the past year (t = −9.93, p < 0.001). They had weaker social connections, reporting more loneliness (r = 0.26, p < 0.001) and less social support (r = −0.21, p < 0.001). They reported being in less secure financial situations (r = −0.30, p < 0.001). They reported higher levels of perceived stress overall (r = 0.37, p < 0.001) and endorsed using more avoidant, short-term-oriented, and self-destructive strategies to cope with relationship and financial stress, including smoking more (t = −8.74, p < 0.001) and drinking more (t = −5.64, p < 0.001). They were less likely to have a bachelor's degree (t = 4.52, p < 0.001) and held lower-status jobs (r = −0.18, p < 0.001). Their jobs were more physically demanding (r = 0.20, p < 0.001) and more likely to cause pain and fatigue (r = 0.23, p < 0.001). They were more likely to believe that they would soon be physically unable to continue working at their current jobs (t = −5.04, p < 0.001). They were more likely to work night shifts (t = −3.07, p = 0.002). Overall, the picture that emerged from the nomological network of the despair factor was consistent with existing conceptualizations of individuals who are most vulnerable to deaths of despair (Case & Deaton, Reference Case and Deaton2021).

Associations between adolescent psychopathology and the midlife despair syndrome

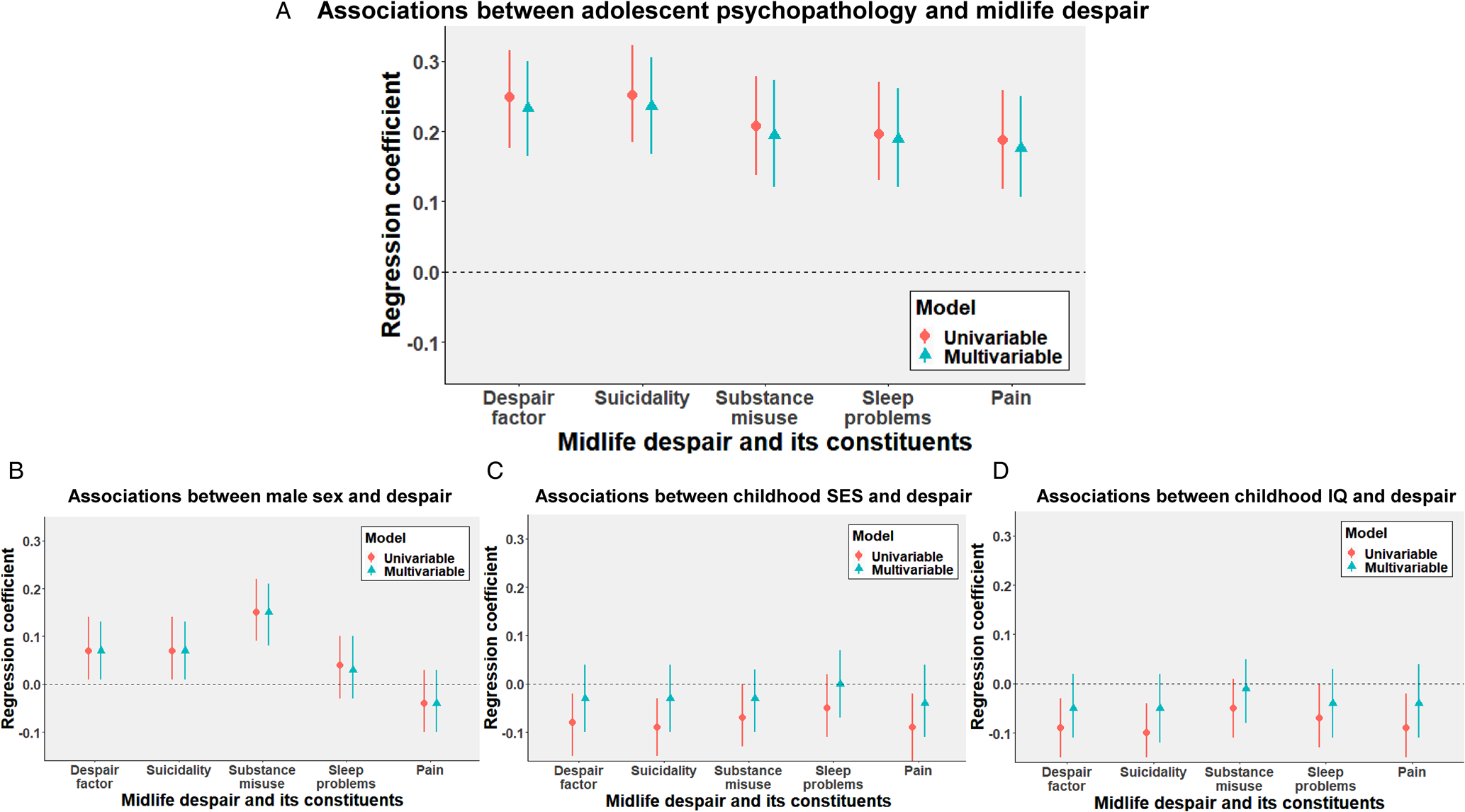

Participants with psychopathology in adolescence had a more severe syndrome of despair-related maladies overall [β = 0.23, 95% CI (0.16–0.30), p < 0.001] and individually – suicidality [β = 0.24, 95% CI (0.17–0.31), p < 0.001], substance misuse [β = 0.19, 95% CI (0.12–0.27), p < 0.001], sleep problems [β = 0.19, 95% CI (0.12–0.26), p < 0.001], and pain [β = 0.18, 95% CI (0.11–0.25), p < 0.001], after adjusting for sex, childhood SES, and childhood IQ (Fig. 2, Panel A; see online Supplementary eTables 3 and 4 for adjusted and unadjusted estimates).

Fig. 2. Adolescent psychopathology is associated with a syndrome of midlife despair and its constituent elements, even after adjusting for sex, childhood SES, and childhood IQ.

Note: Panel A shows the associations between adolescent psychopathology and the despair factor at midlife, Panel B shows the associations between male sex and the midlife despair factor, Panel C shows the associations between childhood SES and the midlife despair factor, and Panel D shows the associations between childhood IQ and the midlife despair factor. Each panel depicts the results for univariable (simple) linear regression models including each risk factor as a single predictor, as well as results for multivariable (multiple) linear regression models including all risk factors as simultaneous predictors. Points and their associated vertical lines represent standardized effect sizes (β) and 95% confidence intervals, respectively. See also eTable 3.

Figure 2, Panels B–D show the associations between sex, childhood SES, and childhood IQ and the midlife despair syndrome (see also online Supplementary eTable 3). Participants who were male, grew up in more deprived socioeconomic circumstances, and had lower IQ scores had more despair-related maladies overall at midlife. However, comparison of effect sizes indicated that associations between adolescent psychopathology and the midlife despair syndrome were generally several times as strong as associations for other risk factors; for example, adolescent psychopathology predicted the midlife despair syndrome 3–4 times more strongly than male sex, lower SES, and lower IQ. Moreover, the effects of more deprived socioeconomic circumstances and lower IQ were no longer significant in the multivariable models.

We also tested whether sex, childhood SES, or childhood IQ moderated the associations between adolescent psychopathology and despair-related maladies overall. We detected no interactions between any of these potential risk factors and adolescent psychopathology in the prediction of despair-related maladies overall (see online Supplementary eTable 5). Sensitivity analyses that used latent factors within the structural equation modeling framework (instead of extracted factor scores; online Supplementary eAppendix 4) and that included 6 additional participants who had died by suicide between ages 26 and 45 (online Supplementary eAppendix 5) yielded virtually indistinguishable results.

Associations between number of mental disorders diagnosed in adolescence and the midlife despair syndrome

Adolescents diagnosed with more mental disorders had a more severe syndrome of despair-related maladies overall [β = 0.26, 95% CI (0.19–0.33), p < 0.001] and individually – suicidality [β = 0.26, 95% CI (0.19–0.33), p < 0.001], substance misuse [β = 0.19, 95% CI (0.11–0.26), p < 0.001], sleep problems [β = 0.21, 95% CI (0.14–0.28), p < 0.001], and pain [β = 0.19, 95% CI (0.12–0.29), p < 0.001], after adjusting for sex, childhood SES, and childhood IQ; Fig. 3, and see online Supplementary eTable 6 for unadjusted estimates).

Fig. 3. Dose-response associations between number of adolescent mental disorders and the midlife despair syndrome.

Note: Panel A shows the association between number of adolescent mental disorders and the despair factor at midlife (z-scored), Panel B shows the association between number of adolescent mental disorders and the suicidality subfactor at midlife (z-scored), Panel C shows the association between number of adolescent mental disorders and the substance misuse subfactor at midlife (z-scored), Panel D shows the association between number of adolescent mental disorders and the sleep problems subfactor at midlife (z-scored), and Panel E shows the association between number of adolescent mental disorders and the pain subfactor at midlife (z-scored). Vertical lines represent ±1 standard error. 0 disorders, N = 580; 1 disorder, N = 212; 2 disorders, N = 67; 3+disorders, N = 24.

Associations between different types of adolescent mental disorder and the midlife despair syndrome

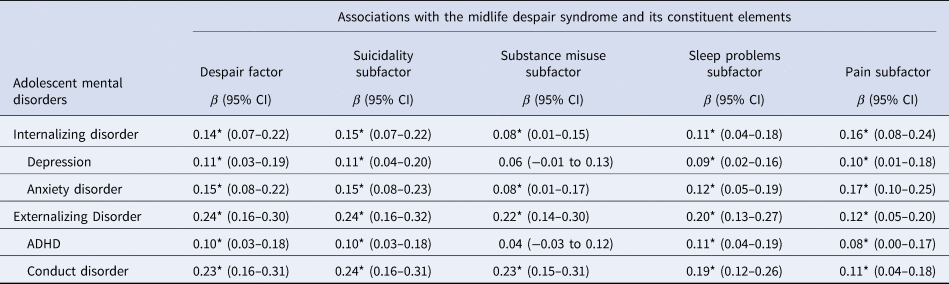

Adolescents who had an internalizing disorder [i.e. depression or an anxiety disorder; β = 0.14, 95% CI (0.07–0.22), p < 0.001] and adolescents who had an externalizing disorder [i.e. ADHD or conduct disorder; β = 0.24, 95% CI (0.16–0.30), p < 0.001] had more despair-related maladies overall at midlife, after adjusting for sex, childhood SES, and childhood IQ. Adolescents with an internalizing or externalizing disorder also had higher levels of each individual despair-related malady at midlife (Table 2). To test for unique effects of internalizing v. externalizing disorders, we also entered both variables into the model as simultaneous predictors. Both internalizing [β = 0.11, 95% CI (0.04–0.17), p < 0.001] and externalizing [β = 0.22, 95% CI (0.15–0.29), p < 0.001] disorders uniquely predicted higher levels of despair-related maladies overall after adjusting for sex, childhood SES, and childhood IQ, as well as higher levels of nearly every individual despair-related malady at midlife (see online Supplementary eTable 7).

Table 2. Each type of adolescent mental disorder was associated with a syndrome of midlife despair

Note. Results displayed are adjusted estimates after adjusting for sex, childhood socioeconomic status, and childhood IQ. CI, confidence interval; ADHD, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. * denotes p < 0.05.

Within the internalizing and externalizing categories, every individual adolescent mental disorder (depression and anxiety disorder; ADHD and conduct disorder) was associated with more despair-related maladies overall and individually at midlife. The sole exception to this pattern was that adolescent depression was not significantly associated with midlife substance misuse (Table 2). All associations remained significant even after adjusting for sex, childhood SES, and childhood IQ, except for the association between adolescent ADHD and midlife substance misuse.

Is adolescent psychopathology associated with midlife despair above and beyond midlife psychopathology?

To address this question, we re-examined the association between adolescent psychopathology and the midlife despair factor after adjusting for age-45 psychopathology (online Supplementary eTable 8), operationalized in two ways: (1) the presence of any mental disorder (excluding alcohol and other substance use disorders, since these are already included in the midlife despair syndrome) at age 45, and (2) the number of mental disorders (again excluding alcohol and other substance use disorders) diagnosed at age 45. Adolescents diagnosed with a mental disorder were more likely to have a mental disorder at age 45 [OR 2.15, 95% CI (1.60–2.89), p < 0.001] and were diagnosed with more mental disorders at age 45 [β = 0.21, 95% CI (0.13–0.28), p < 0.001] than adolescents without a mental disorder. Even after adjusting for age-45 mental disorders, the association between adolescent psychopathology and the general midlife despair factor remained significant [β = 0.20, 95% CI (0.13–0.27), p < 0.001], beyond any age-45 mental disorder; β = 0.17, 95% CI (0.11–0.23), p < 0.001, beyond the sum of age-45 mental disorders; see online Supplementary eTable 8).

Discussion

Findings from this longitudinal cohort study provide support for the hypothesis that individuals who exhibited more despair-related maladies at midlife, as captured by four interrelated subdomains – suicidality, substance misuse, sleep problems, and pain – tended to have had psychopathology in adolescence. Individuals with a more severe midlife despair syndrome also had more mental disorders as adolescents, and associations were not specific to any particular adolescent mental disorder or any particular subdomain of the midlife despair syndrome. Previous research suggests that psychopathology is associated with poorer health and diminished wellbeing later in life (Devendorf, Rum, Kashdan, & Rottenberg, Reference Devendorf, Rum, Kashdan and Rottenberg2022; Goodwin et al., Reference Goodwin, Sourander, Duarte, Niemela, Multimaki, Nikolakaros and Almqvist2009; Richmond-Rakerd, D'Souza, Milne, Caspi, & Moffitt, Reference Richmond-Rakerd, D'Souza, Milne, Caspi and Moffitt2021; Scott et al., Reference Scott, Lim, Al-Hamzawi, Alonso, Bruffaerts, Caldas-de-Almeida and Kessler2016). Our results extend previous findings in two ways. First, they provide a unified model for conceptualizing the interrelated maladies that comprise a midlife despair syndrome. Second, they trace the origins of the midlife despair syndrome back to psychopathology in adolescence, providing initial evidence for a robust early-life risk factor for multiple midlife despair-related maladies. Importantly, associations between adolescent psychopathology and the midlife despair syndrome could not be explained by other childhood risk factors, including deprived socioeconomic origins and low IQ.

The higher-order factor model of midlife despair-related maladies suggests that symptoms across four separate but interrelated domains – suicidality, substance misuse, sleep problems, and pain – coalesced to form a single overarching despair factor at midlife, which may represent a desire to escape from psychic and physical suffering. The roles of suicidality and substance misuse in causing deaths of despair (via suicides, drug overdoses, and alcohol-related liver disease) are already recognized. Indeed, based on the finding that the suicidality subfactor loaded so strongly (i.e. 0.96) on the general despair factor at midlife, it may be that suicidality represents the ultimate expression of despair. However, our findings suggest that sleep problems and pain should also be considered part of the constellation of despair-related maladies. Both are associated with decrements in functioning (Briggs et al., Reference Briggs, Cross, Hoy, Sànchez-Riera, Blyth, Woolf and March2016; Stranges, Tigbe, Gómez-Olivé, Thorogood, & Kandala, Reference Stranges, Tigbe, Gómez-Olivé, Thorogood and Kandala2012; Zelaya, Dahlhamer, Lucas, & Connor, Reference Zelaya, Dahlhamer, Lucas and Connor2020) and increased mortality (Grandner, Hale, Moore, & Patel, Reference Grandner, Hale, Moore and Patel2010; Smith, Wilkie, Croft, Parmar, & McBeth, Reference Smith, Wilkie, Croft, Parmar and McBeth2018) as individuals age, and our findings suggest that they may contribute indirectly to mortality through their associations with suicidality and substance misuse (Case & Deaton, Reference Case and Deaton2021; Chakravorty, Chaudhary, & Brower, Reference Chakravorty, Chaudhary and Brower2016; Harris, Huang, Linthicum, Bryen, & Ribeiro, Reference Harris, Huang, Linthicum, Bryen and Ribeiro2020; Valentino & Volkow, Reference Valentino and Volkow2020). Clinically, our findings suggest that sleep problems and pain should be included in comprehensive assessments of mental health in midlife patients. Relatedly, midlife adults presenting for treatment at a mental health clinic, substance abuse clinic, sleep clinic, or pain clinic are likely to have other despair-related maladies in addition to their presenting concern, highlighting the need for coordinated interprofessional team-based care (Holmboe, Singer, Chappell, Assadi, Salman, & the Education & Training Working Group of the National Academy of Medicine; Action Collaborative on Countering the U.S. Opioid Epidemic, Reference Holmboe, Singer, Chappell, Assadi and Salman2022).

Results support the generality (rather than specificity) of associations between adolescent psychopathology and the midlife despair syndrome, consistent with previous research suggesting that psychopathology confers non-specific risk for poorer aging-related outcomes at midlife (Wertz et al., Reference Wertz, Caspi, Ambler, Broadbent, Hancox, Harrington and Moffitt2021). Yet despite the pattern suggesting that it does not matter which mental disorder one has, having more comorbid adolescent mental disorders appeared to confer greater risk for the midlife despair syndrome. This pattern is consistent with previous research suggesting accumulative effects of psychopathology on individual despair-related maladies (Stone, Vander Stoep, & McCauley, Reference Stone, Vander Stoep and McCauley2016; Verona, Sachs-Ericsson, & Joiner, Reference Verona, Sachs-Ericsson and Joiner2004).

Importantly, associations between adolescent psychopathology and the midlife despair syndrome were not explained away after adjusting for other factors known to increase risk for despair-related maladies (i.e. male sex, more deprived socioeconomic origins, lower childhood IQ). Associations were attenuated after adjusting for age-45 psychopathology, but remained significant, suggesting that the midlife despair syndrome is not redundant with midlife psychopathology in general, and observed associations do not merely reflect the continuity of psychopathology across the lifecourse. In addition to being a robust predictor, adolescent psychopathology also outperformed other potential risk factors in forecasting the midlife despair syndrome, with effect sizes multiple times as large (Fig. 2). These robust and relatively large effects provide support for the relevance of the observed associations, particularly given recent increases in the rates of childhood mental health problems globally (Racine et al., Reference Racine, McArthur, Cooke, Eirich, Zhu and Madigan2021) and calls to address the burgeoning youth mental health crisis (American Academy of Pediatrics, 2021; Office of the Surgeon General (OSG), 2021). Left unaddressed, this crisis may portend a swelling plague of midlife despair – and its attendant disability and mortality – in the coming decades.

Our findings have implications for future research, prevention, and health policy. First, our findings provide a foundation for future research examining the mechanisms linking adolescent psychopathology to a syndrome of midlife despair. Possible mechanisms include biological (e.g. common genetic vulnerability), psychological (e.g. stressful life experiences), social (e.g. erosion of social connections), educational/occupational (e.g. curtailed educational attainment), and lifestyle (e.g. poor health behaviors) factors. Second, if the association between adolescent psychopathology and the midlife despair syndrome turns out to be causal, prevention and treatment of psychopathology early in life has the potential to mitigate despair-related maladies and reduce deaths of despair (Deković et al., Reference Deković, Slagt, Asscher, Boendermaker, Eichelsheim and Prinzie2011; Swan et al., Reference Swan, Kendall, Olino, Ginsburg, Keeton, Compton and Albano2018). Third, even if adolescent psychopathology is merely a marker (rather than a true cause) of vulnerability for the midlife despair syndrome, policies are needed that protect this vulnerable population by prioritizing them to receive education and services.

This study has several limitations. First, the participants self-identified as predominantly White and originated only from New Zealand. Although New Zealand has not appeared to experience the same rise in deaths of despair as the U.S., mortality rates and deaths of despair in New Zealand show the same demographic patterning as in the U.S. – that is, they tend to cluster within more disadvantaged and less educated people (Blakely et al., Reference Blakely, Tobias and Atkinson2008; Richmond-Rakerd, D'Souza, Milne, & Andersen, Reference Richmond-Rakerd, D'Souza, Milne and Andersenunder review). Moreover, although income inequality is not as high in New Zealand as in the U.S., New Zealand still ranks 13th highest among the 38 OECD countries (8 places below the U.S. and 5 below the U.K.; OECD, 2022). Although the Dunedin Study has a good track record for replication of findings across a variety of domains [e.g. crime, personality, and psychopathology (Caspi et al., Reference Caspi, Moffitt, Silva, Stouthamer-Loeber, Krueger and Schmutte1994); parenting behavior (Reference Wertz, Moffitt, Arseneault, Barnes, Boivin, Corcoran and CaspiWertz et al., in press); social mobility (Belsky et al., Reference Belsky, Domingue, Wedow, Arseneault, Boardman, Caspi and Harris2018)], it is unknown whether the present study's findings will replicate in other geographic regions or ethnic groups. Second, participants who had died by suicide well before midlife (i.e. before age 26; N = 2) were not included in any analyses because we did not want to count suicides that occurred well before midlife as evidence of midlife despair. Third, this study was observational and thus cannot establish whether observed associations are causal. Future studies are necessary to ascertain whether the observed associations between adolescent psychopathology and the midlife despair syndrome are modifiable through mental health treatment. Fourth, we were unable to test a longitudinal path model from psychopathology to educational failure to difficult working conditions to pain and sleep problems to prescription medication to the despair syndrome including substance misuse, because our study lacked measures in the hypothesized sequential order (and power); however, we hope these findings will inspire researchers to test the implied causal model. Finally, we measured indicators of despair-related maladies but not actual deaths. Therefore, establishing direct connections to deaths of despair would require additional study and replication using other data sources. These limitations should be considered in light of the study's strengths, which include the use of measures of despair across multiple modalities, the decades-long timeframe of investigation, and the setting in New Zealand (allowing us to disentangle despair-related maladies from the opioid epidemic experienced in other countries such as the U.S.).

In conclusion, the findings of this cohort study suggest that individuals who exhibited a more severe syndrome of despair at midlife tended to have had a mental disorder in adolescence. Prevention and treatment of adolescent psychopathology could reduce vulnerability to the midlife despair syndrome and thereby lengthen the healthspans and lifespans of aging adults.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291723001320

Acknowledgments

The Dunedin Multidisciplinary Health and Development Research Unit at University of Otago is within the Ngāi Tahu tribal area who we acknowledge as first peoples, tangata whenua (translation: people of this land). We thank the Dunedin Study members, their peer informants, Unit research staff, and Study founder Phil Silva.

Financial support

The Dunedin Multidisciplinary Health and Development Research Unit is supported by the New Zealand Health Research Council (Programme Grant 16-604) and New Zealand Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment (MBIE). This research was supported by grants R01AG032282 and R01AG069939 from the US National Institute on Aging (NIA) and grant MR/P005918/1 from the UK Medical Research Council. It was also supported by the Duke Aging Center Postdoctoral Research Training Grant (NIA T32 AG000029). Additional support was provided by the Jacobs Foundation.

Conflict of interest

None.