Rates of suicide mortality (Griffin et al., Reference Griffin, Grimm, Smart, Ramchand, Jaycox, Ayer and Morral2020; Psychological Health Center of Excellence, 2021) and non-fatal suicide attempts (SAs) (Ursano et al., Reference Ursano, Kessler, Heeringa, Cox, Naifeh, Fullerton and Stein2015a) among U.S. Army soldiers increased significantly during the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan and remain elevated. Detecting suicidal behavior is fundamental to treatment, prevention, resource allocation, and mental health care program planning. Military clinicians, program planners, and leaders rely on multiple mechanisms to identify suicide-related outcomes, including medical records (Centers for Disease Control & Prevention, 2013, 2019; Hedegaard et al., Reference Hedegaard, Schoenbaum, Claassen, Crosby, Holland and Proescholdbell2018), and the Department of Defense Suicide Event Report (DoDSER) (Gahm et al., Reference Gahm, Reger, Kinn, Luxton, Skopp and Bush2012). However, there are several factors that determine whether SAs are identified, including willingness to report them to clinicians, partners, peers, supervisors, and leaders (Schafer et al., Reference Schafer, Duffy, Kennedy, Stentz, Leon, Herrerias and Joiner2022; Sheehan et al., Reference Sheehan, Oexle, Armas, Wan, Bushman, Glover and Lewy2019; Zuromski et al., Reference Zuromski, Dempsey, Ng, Riggs-Donovan, Brent, Heeringa and Nock2019). The extent to which soldiers are making SAs that are not identified in the healthcare system is unknown. To our knowledge, no existing research has examined the prevalence or correlates of undetected SAs within the Army population. In fact, few studies, military or civilian, have the capability to do so. Undetected SAs are not directly addressed by current theories of suicidal behavior (Selby, Joiner, & Ribeiro, Reference Selby, Joiner, Ribeiro and M. K.2014), yet they are important in all healthcare populations. The Army Study to Assess Risk and Resilience in Servicemembers (Army STARRS) (Ursano et al., Reference Ursano, Colpe, Heeringa, Kessler, Schoenbaum and Stein2014) provides an opportunity to develop initial estimates of the size of this complex issue within the U.S. Army healthcare system. In doing so, it may encourage other healthcare systems to begin examining undetected SAs within their own patient populations, and it may also encourage consideration of these events in theories of suicidal behavior. Understanding the scope and impact of undetected SAs is necessary to better predict suicide risk and create opportunities for early intervention.

Few studies have addressed the concordance between military SAs reported in the context of survey research and SAs documented in medical data. This is meaningful, as barriers to behavioral healthcare utilization, and therefore identification in the healthcare system, have been found to vary based on sociodemographic characteristics such as race and gender (Wong et al., Reference Wong, Meadows, Schell, Chan, Jaycox, Osilla and Roth2021), and service-level characteristics such as rank (Ho, Burchett, Osborn, Smith, & Schechter, Reference Ho, Burchett, Osborn, Smith and Schechter2019). Certain vulnerable populations may be disproportionately impacted by barriers to disclosing SAs to healthcare providers. Thus, research is needed to understand how often SAs go undetected and who is most likely to make an undetected SA.

Army STARRS provides a unique opportunity to examine undetected SAs using a large, representative survey in which soldiers’ self-reported questionnaire responses are linked to their Army and Department of Defense (DoD) administrative medical records. Given that nearly all medical care for soldiers is captured in their Army/DoD administrative records (unlike many other populations), soldiers who report an in-service SA but have no administrative medical documentation of an attempt can be classified as having an undetected SA. The current study used this novel combination of survey and administrative medical data to (a) estimate the prevalence and incidence of undetected SAs during Army service, (b) examine sociodemographic characteristics associated with having an undetected SA, and (c) identify characteristics of undetected SAs, including when they occur during service and the severity of SA-related injuries.

Method

Participants

The consolidated All-Army Survey (AAS) includes data collected from three Army STARRS survey components, which together are representative of non-deployed soldiers, soon-to-deploy soldiers, and deployed soldiers (in-theater at the time of the survey). In each survey component, respondents providing written informed consent were asked to complete a self-administered questionnaire (SAQ) and consent to linkage of their survey responses and Army/DoD administrative records. The largest component was a representative survey of non-deployed soldiers who were not in Initial Military Training. It was carried out in 2011–2012 and contributed 17 462 respondents to the consolidated AAS (95.0% survey consent rate; 97.3% survey completion rate among consenters; 63.1% administrative data linkage consent rate among survey completers). The second component, a survey of deployed soldiers transiting through Kuwait in 2013 for their mid-deployment leave from Afghanistan, contributed 3987 respondents to the consolidated AAS (80.9% survey consent rate; 86.5% survey completion rate among consenters; 55.6% administrative data linkage consent rate among survey completers). The third survey consisted of soldiers from three Brigade Combat Teams preparing to deploy to Afghanistan in 2013 and contributed 8558 respondents to the consolidated AAS (98.7% survey consent rate; 99.2% survey completion rate among consenters; 90.9% administrative data linkage consent rate among survey completers). The survey-linked administrative data were used to create person-month records by coding each month of a soldier's career separately for each administrative variable and allowing values to change over time (Singer & Willett, Reference Singer and Willett2003; Willett & Singer, Reference Willett and Singer1993).

Data from each survey were doubly-weighted to adjust for differences in responses from soldiers who did v. did not consent to administrative data linkage, and for inconsistencies between those consenting soldiers and the target population. Specifically, we obtained de-identified administrative data for the entire Army and for survey respondents who agreed to administrative data linkage, allowing two weights to be created to adjust for non-response bias (i.e. discrepancies between the analytic sample and target population). Each weight was constructed based on an iterative process of stepwise logistic regression analysis designed to arrive at a stable weighting solution. Weight 1 (W1) adjusted for discrepancies between survey completers with v. without administrative record linkage based on a prediction equation that used SAQ responses (e.g. items assessing mental disorders, suicidal thoughts and behaviors, head injuries, exposure to combat and other stressful events, etc.) as predictors: W1 = 1/p1, where p1 is the probability of consenting to administrative data linkage. Weight 2 (W2) adjusted for discrepancies between weighted (W1) survey completers with record linkage and the target population based on a prediction equation that used a small set of administrative variables as predictors (e.g. age, sex, rank): W2 = 1/p2, where p2 is the probability of survey completion. These doubly-weighted (W1 × W2) data were used in all of the current study's analyses. Additional details regarding the methods used for data collection and weighting are available elsewhere (Heeringa et al., Reference Heeringa, Gebler, Colpe, Fullerton, Hwang, Kessler and Ursano2013; Kessler et al., Reference Kessler, Heeringa, Colpe, Fullerton, Gebler, Hwang and Ursano2013). Consent and data collection procedures were approved by the Human Subjects Committees of the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, the University of Michigan Institute for Social Research, and all other collaborating organizations. In the current study, we focus on the 24 475 Regular Army enlisted respondents who agreed to have their survey data linked to their Army administrative data and had non-missing survey dates.

Measures

Documented SA

Administratively documented non-fatal SAs were identified using: DoDSER (Gahm et al., Reference Gahm, Reger, Kinn, Luxton, Skopp and Bush2012) records; and codes from ICD-9-CM (E950-E958; indicating self-inflicted poisoning/injury with suicidal intent) (Centers for Disease Control & Prevention, 2013) and ICD-10-CM (X71-X83, indicating intentional self-harm; and T36-T65 and T71, where the 5th or 6th character indicates intentional self-harm; and T14.91, indicating SA, not otherwise specified) (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2019; Hedegaard et al., Reference Hedegaard, Schoenbaum, Claassen, Crosby, Holland and Proescholdbell2018) in data systems capturing healthcare encounter information from military and civilian treatment facilities, combat operations, and aeromedical evacuations (online Supplementary Table S1).

Undetected SA

Soldiers who reported an in-service SA but did not have a documented attempt (as defined above) prior to the survey were classified as having an undetected SA. Self-reported SAs were assessed via SAQ using a modified version of the Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS) (Posner et al., Reference Posner, Brown, Stanley, Brent, Yershova, Oquendo and Mann2011). Respondents were first asked about lifetime occurrence of suicidal ideation using two questions (Did you ever wish you were dead or would go to sleep and never wake up? or Did you ever in your life have thoughts of killing yourself?). Those who endorsed SI were administered additional suicide assessment questions, including lifetime occurrence of SA (e.g. Did you ever make a suicide attempt; that is, purposefully hurt yourself with at least some intention to die?). Soldiers who endorsed a lifetime history of SA were asked to provide the ages at which their first and most recent SAs occurred. We identified individuals with an in-service SA by comparing the reported ages of first and most recent SA with their age at Army accession. We then identified which of the respondents reporting an in-service SA did not have a documented SA between their date of accession and their survey date.

To estimate the month of service in which an undetected SA occurred during a soldier's Army career, we calculated the difference between the respondent's date of accession and the date of their undetected attempt. The date of undetected SA was estimated by first taking either the reported age at first attempt (for those whose first or only SA occurred during service) or age at most recent attempt (for those with SAs before and during service). Then, given that the specific timing of the attempt during the reported age was unknown, we selected the mid-point of that year of life by adding 6 months to the month of birth. We then identified which month of service the soldier was in at the time of the undetected SA.

Severity of SA

The SAQ assessed the severity of SA-related injuries using a modified version of the C-SSRS (Posner et al., Reference Posner, Brown, Stanley, Brent, Yershova, Oquendo and Mann2011). Respondents were asked about the severity of their most serious injuries received from a SA (What were the most serious injuries you ever received from a suicide attempt?). Response options included the following: (1) No injury or very minor injury (e.g. surface scratches, mild nausea), (2) Minor injury (e.g. sprain, first degree burns, flesh wound), (3) Moderate injury not requiring overnight hospitalization (e.g. broken bones, second degree burns, stitches, bullet lodged in arm or leg), (4) Moderate injury requiring overnight hospitalization (e.g. major fracture, third degree burns, coma, bullet lodged in abdomen or chest, minor surgery), and (5) Severe injuries requiring treatment in an intensive care unit to save life (e.g. major fracture of skull or spine, severe burns, coma requiring respirator, bullet in head, major surgery).

Sociodemographic characteristics

Sociodemographic characteristics were identified through either self-report on the SAQ (gender, age, race/ethnicity, education, marital status) or administrative personnel records (rank).

Mental health diagnosis

Administrative medical records were used to create an indicator variable for mental health diagnosis (MH-Dx) during Army service based on ICD-9-CM and ICD-10-CM mental health diagnostic codes, excluding mental health-related V-codes and Z-codes (online Supplementary Table S2).

Data analysis

Analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., 2013). First, we estimated the prevalence rate for undetected SA during Army service. Annual incidence was calculated based on the weighted number of soldiers with an undetected SA and the total number of at-risk person-months represented by the weighted sample (i.e. the total number of person-months between the start of service and the survey date). Logistic regression analyses examined the univariable and multivariable association of each sociodemographic characteristic with undetected SA. Logistic regression coefficients and confidence limits were exponentiated to obtain estimated odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI). Standard errors were estimated using the Taylor series method (Wolter, Reference Wolter1985) to adjust for the weighting and clustering of survey data. Significance tests in the logistic regression analyses were made using F-tests adjusted for design effects using the Taylor series method. Statistical significance was evaluated using two-sided design-based tests and p < 0.05 significance level.

A series of Rao-Scott chi-square tests examined whether gender or SA-related injury severity differed among soldiers who did v. did not receive a MH-Dx prior to their undetected SA. In addition, a discrete-time survival model (Singer & Willett, Reference Singer and Willett2003; Willett & Singer, Reference Willett and Singer1993) was used to estimate risk of undetected SA (per 100 000 person-years) as a function of time in-service. Poisson regression was then used to examine whether risk of undetected SA differed by year of service.

Results

Sample characteristics

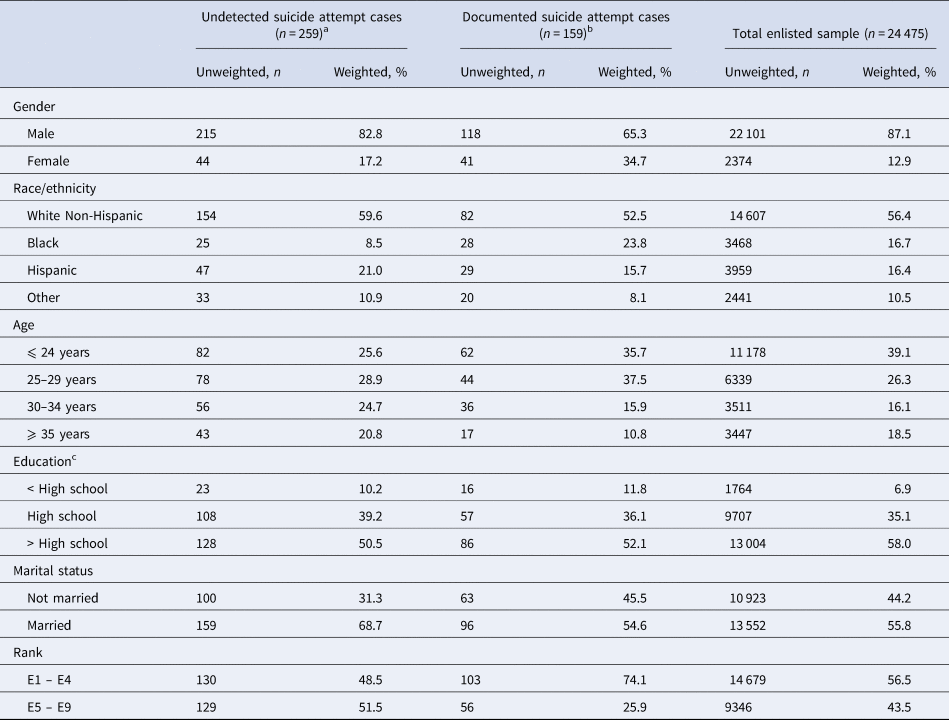

The weighted sample of enlisted survey respondents was mostly male (87.1%), White Non-Hispanic (56.4%), younger than 30-years-old (65.4%), more than high school-educated (58.0%), married (55.8%), and E1-E4 rank (56.5%) (Table 1). Lifetime SA was reported by 3.3% of respondents, of whom 53.2% were estimated to have made at least one SA during service. Among those reporting an in-service SA, n = 259 (unweighted) did not have a documented SA in their administrative medical records prior to the survey and therefore were classified as having an undetected SA (2.8% of whom had a documented SA after the survey). Soldiers with an undetected SA were mostly male (82.8%), White Non-Hispanic (59.6%), younger than 30-years-old (54.5%), more than high school-educated (50.5%), married (68.7%), and E5-E9 rank (51.5%). The 0.7% (unweighted n = 159) of respondents with a documented SA prior to the survey were mostly male (65.3%), White Non-Hispanic (52.5%), younger than 30-years-old (73.2%), more than high school-educated (52.1%), married (54.6%), and E1-E4 rank (74.1%) (Table 1).

Table 1. Distribution of sociodemographic characteristics among Regular Army enlisted soldiers from the Army STARRS consolidated All Army Study

a Undetected suicide attempt cases are survey respondents who self-reported an in-service suicide attempt but had no documentation of an attempt in their Army/DoD administrative medical records prior to the survey.

b Documented suicide attempt cases are survey respondents who had a suicide attempt documented in their Army/DoD administrative medical records prior to the survey.

c < High school = General Educational Development credential (GED) or equivalent; High school = high school diploma; >High school = some post-high school education but no certificate or degree, post-high school technical school certificate or degree, 2-year college Associate Degree, or 4-year college degree.

Prevalence and incidence rate of undetected SA

The estimated prevalence of having an undetected SA during service was 1.3% of soldiers at the time of the survey. Based on the weighted number of soldiers with an undetected SA (N = 7049.7) and the total number of at-risk person-months represented by weighted the sample (N = 33 003 194 person-months), the estimated annual incidence rate of undetected SA prior to the survey was 255.6 per 100 000 person-years.

Soldier characteristics that differentiate undetected SAs from documented SAs

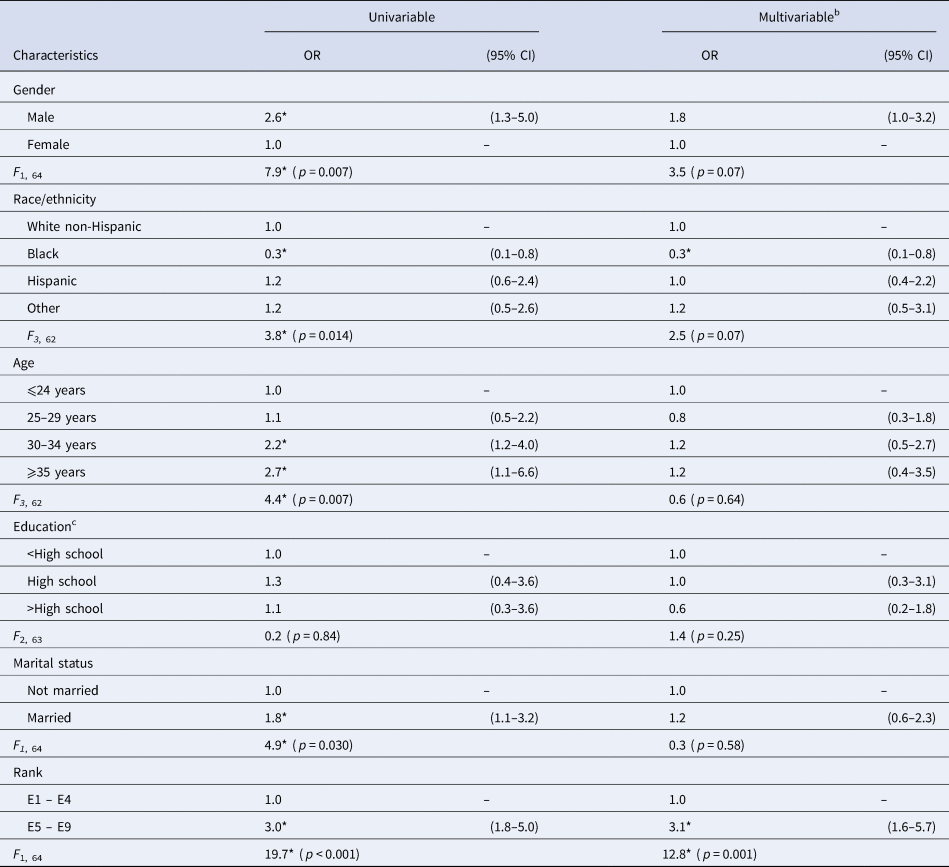

In univariable analyses, gender, race/ethnicity, age, marital status, and rank significantly differentiated soldiers with an undetected SA from those with a documented SA. Odds of undetected SA were higher among those who were male, older, married, and higher ranking, and lower among those identifying as Black (v. White non-Hispanic). When all sociodemographic variables were examined simultaneously in the same model, only Army rank remained significant, with higher odds of undetected SA among soldiers with an enlisted rank ⩾E5 (OR = 3.1[95%CI 1.6–5.7]) (Table 2).

Table 2. Associations of sociodemographic characteristics with undetected suicide attempts v. documented suicide attempts among Regular Army enlisted soldiersa

a The Regular Army enlisted soldiers considered here (unweighted n = 677) are survey respondents from the Army STARRS consolidated All Army Study who reported an in-service suicide attempt on the self-administered questionnaire and/or had an administratively documented suicide attempt prior to the survey date.

b Logistic regression model includes all sociodemographic variables (gender, race/ethnicity, education, marital status, and rank).

c < High school = General Educational Development credential (GED) or equivalent; High school = high school diploma; >High school = some post-high school education but no certificate or degree, post-high school technical school certificate or degree, 2-year college Associate Degree, or 4-year college degree.

*p < 0.05.

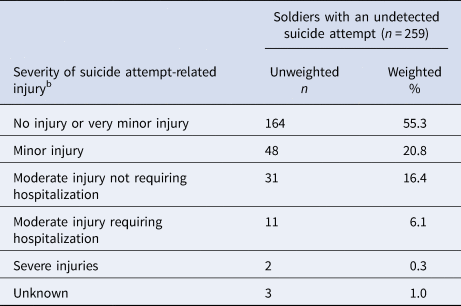

Severity of injury following undetected SA

More than one-fifth (22.8%) of soldiers with an undetected SA reported attempt-related injuries of moderate severity or greater, including 6.4% who reported injuries that resulted in hospitalization, whereas 76.1% reported minor or no injury (Table 3). This pattern of results was confirmed in the subset of respondents with a single lifetime undetected SA that occured during service (online Supplementary Table S3).

Table 3. Severity of suicide attempt-related injury among Regular Army enlisted soldiers with an undetected suicide attempt

a The Regular Army enlisted soldiers considered here (unweighted n = 259) are survey respondents from the Army STARRS consolidated All Army Study with an undetected suicide attempt (i.e. respondents with a self-reported suicide attempt during Army service but no administrative medical documentation of a suicide attempt).

b Respondents indicated the severity of their most serious injuries received from a SA. Response options included the following: (1) No injury or very minor injury (e.g. surface scratches, mild nausea), (2) Minor injury (e.g. sprain, first degree burns, flesh wound), (3) Moderate injury not requiring overnight hospitalization (e.g. broken bones, second degree burns, stitches, bullet lodged in arm or leg), (4) Moderate injury requiring overnight hospitalization (e.g. major fracture, third degree burns, coma, bullet lodged in abdomen or chest, minor surgery), and (5) Severe injuries requiring treatment in an intensive care unit to save life (e.g. major fracture of skull or spine, severe burns, coma requiring respirator, bullet in head, major surgery).

MH-Dx prior to undetected SA

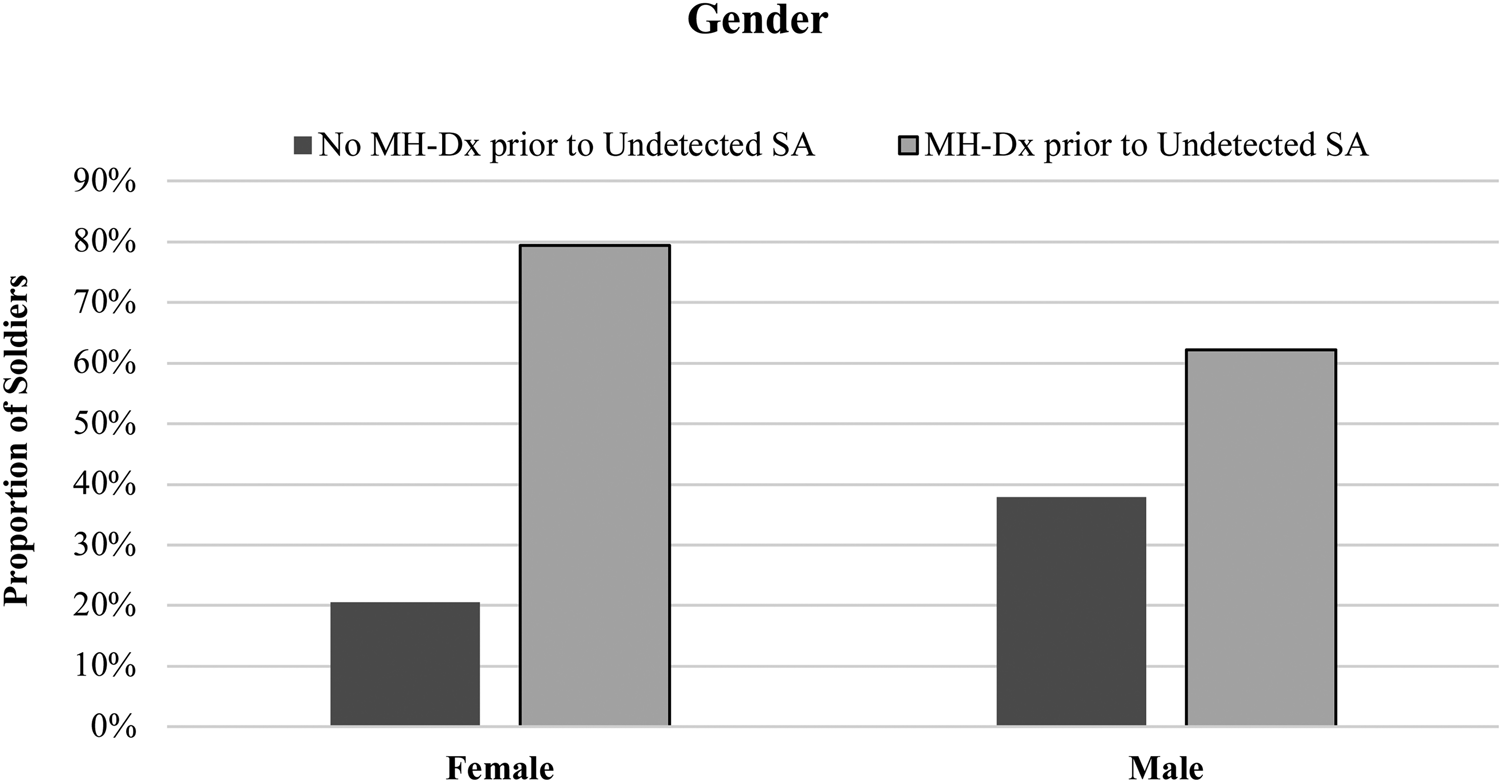

Among soldiers with an undetected SA, 71.1% had received a MH-Dx prior to the date of their undetected attempt and were therefore identified in the mental healthcare system (nearly all [92.9%] received a MH-Dx at some point before or after the survey). Females were significantly more likely than males to have received a MH-Dx prior to their undetected SA (79.4% v. 62.1%; Rao-Scott χ21 = 6.1, p = 0.01) (Fig. 1). Severity of SA-related injury did not differ for those with v. without a MH-Dx prior to their undetected SA.

Figure 1. Gender by mental health diagnosis (MH-Dx) prior to undetected suicide attempt (SA) among Regular Army enlisted soldiers. Female soldiers were significantly more likely than male soldiers to have received a MH-Dx prior to their undetected SA (79.4% v. 62.1%; Rao-Scott χ 21 = 6.1, p = 0.01).

Risk of undetected SA by time in-service

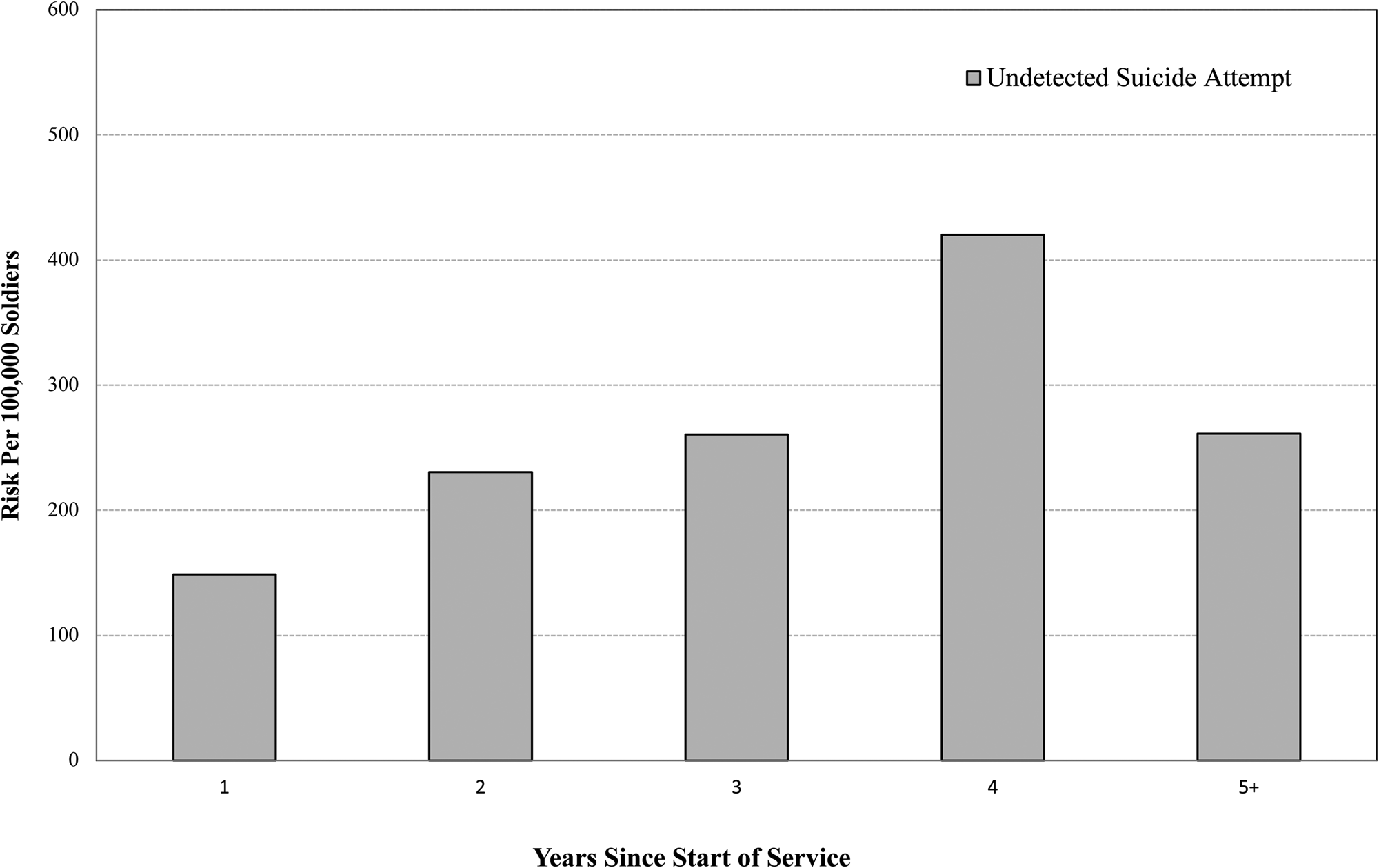

A discrete-time survival model was used to estimate risk of a retrospectively reported, undetected SA by time since entering Army service. Given small N's, monthly risk estimates were averaged to create yearly estimates (per 100 000 soldiers) (Fig. 2). Poisson regression indicated that risk of undetected SA differed by year of service (χ 24 = 423.4, p < 0.0001). Risk was higher in the first four years of service, peaking at 420 per 100 000 soldiers, and lower for those in their fifth year and beyond (average yearly risk = 262 per 100 000 soldiers).

Figure 2. Risk of undetected suicide attempt by time in service among Regular Army enlisted soldiers. Poisson regression indicated that risk of undetected SA (per 100 000 soldiers) differed by year of service (χ 24 = 423.4, p < 0.0001).

Discussion

There are groups of people at risk for suicidal behavior who are particularly difficult to identify. One such group is composed of people who never receive a MH-Dx, and therefore are not identified in the mental healthcare system, prior to their SA (Simonetti et al., Reference Simonetti, Piegari, Maynard, Brenner, Mori, Post and Trivedi2020; Ursano et al., Reference Ursano, Kessler, Naifeh, Herberman Mash, Nock, Aliaga and Stein2018). Another group is people who make undetected SAs, including SAs that were never documented in administrative medical records. Historically, undetected SAs have been challenging to study, especially in the context of representative population survey research, which rarely includes linkage to medical data. Capturing and accurately estimating rates of undetected SAs in military populations has its own set of challenges, including early attrition among service members with mental health problems (Hoge, Auchterlonie, & Milliken, Reference Hoge, Auchterlonie and Milliken2006; Ireland, Kress, & Frost, Reference Ireland, Kress and Frost2012). Addressing those challenges will ultimately require intensive longitudinal survey research specifically designed to assess the incidence, characteristics, risk factors, and consequences of undetected SAs. The current study represents a first step in the process of trying to identify and understand these important events. Using a novel combination of cross-sectional population survey data and linked administrative medical records that capture nearly all medical care received by soldiers, this study provides an examination of the prevalence, incidence, and correlates of undetected SA among those serving in the U.S. Army. The findings indicate that the risk of SA during Army service is higher than previously estimated. Approximately 1.3% of soldiers serving have had an undetected SA sometime during their Army service. The annual incidence of undetected SA among Regular Army enlisted soldiers serving on active duty was 255.6 per 100 000. Of note, the annual rate of documented SA among Regular Army enlisted soldiers during 2004–2009 was 377 per 100 000 soldiers (Ursano et al., Reference Ursano, Kessler, Stein, Naifeh, Aliaga, Fullerton and Heeringa2015b), suggesting that approximately one in three SAs goes undetected. This is likely a conservative estimate given attrition from service. While the prevalence of all in-service SAs in our Army sample (1.8%) is higher than the SA rate among sociodemographically-adjusted U.S. civilians (1.2%) (Nock et al., Reference Nock, Stein, Heeringa, Ursano, Colpe, Fullerton and Kessler2014), the rate of undetected SAs in the civilian population is likely higher than in the Army due to factors that facilitate identification of SAs among soldiers (e.g. universal healthcare, required annual medical examinations, and mental health screening programs).

Our analyses found that soldiers with an undetected SA were differentiated from those with a documented SA by most sociodemographic characteristics in univariable analyses, but only by rank in a multivariable model. Odds of undetected SA were significantly elevated among soldiers with higher rank. This difference is potentially important, as detection and prevention efforts based on existing risk models may be more likely to identify and target soldiers at risk for a documented SA, but not those at risk for an undetected SA. Additional research is needed to better understand how current risk models relate to soldiers with an undetected SA. It is also important to improve understanding of soldiers’ behavior and perceived barriers related to disclosing SAs to providers, leaders, and peers, and how these behaviors and barriers may vary across rank and other military characteristics. It should also be noted that although individuals with undetected SAs likely have multiple suicide-related risk factors, they must have performed reasonably well as soldiers to have remained in service, particularly those who continued beyond their first term of enlistment (typically 4 years). Related to this, very few soldiers with an undetected SA went on to make a documented SA post-survey.

Importantly, 71.1% soldiers with an undetected SA received a MH-Dx prior to their attempt, indicating that nearly 29% had not been identified as needing mental health care before their SA. This is similar to reported rates for documented SAs, where 36% have not had a MH-Dx prior to their SA (Ursano et al., Reference Ursano, Kessler, Naifeh, Herberman Mash, Nock, Aliaga and Stein2018). Identifying this group of at-risk soldiers who are unknown to the mental healthcare system is challenging. There is a need and an opportunity to better understand risk detection and prevention within established points of healthcare contact. Primary care is an important point of contact for identifying risk among those who have no MH-Dx and therefore have not been identified as needing mental health care. However, even for those who do receive a MH-Dx, the challenges of identifying which individuals are at risk of SA remain substantial. Women were more likely than men to have received a MH-Dx prior to their undetected SA, which is consistent with existing literature on gender differences in the prevalence of mental health symptomatology and diagnosis (Narrow, First, Sirovatka, & Regier, Reference Narrow, First, Sirovatka and Regier2007). The high prevalence of MH-Dx before an undetected SA may indicate those soldiers are seeking support for mental health symptoms; and further, that the mental healthcare system is documenting that they could benefit from clinical intervention. In addition to examining more about the context of MH-Dx received prior to an undetected SA, it would be valuable for future longitudinal research to consider the role of undiagnosed mental disorders, as well as other psychological and behavioral characteristics that may be important to understanding undetected SAs and further differentiating them from SAs that are documented.

A substantial minority (22.8%) of soldiers with an undetected SA reported injuries of moderate severity or greater, with more than 1 in 20 reporting injuries severe enough to require hospitalization. Despite self-reported serious injury and hospitalization, these injuries were never linked to a SA in the administrative medical record. Presumably, this is because the SA was never disclosed by the patient or identified as such by the providers. Some of this may be alleviated through better provider training in, and consistent application of, standardized approaches to identifying, labeling, and documenting suicidal behaviors that present in military and other healthcare settings, such as the uniformed definitions for self-directed violence proposed by the Centers for Disease Control (Crosby, Ortega, & Melanson, Reference Crosby, Ortega and Melanson2011). There is also a need for new survey research that examines predictors of, and reasons for, disclosure or nondisclosure to medical providers following a SA, particularly a SA resulting in severe injury requiring hospitalization. Additionally, although receiving a MH-Dx prior to the undetected SA was not associated with severity of SA-related injuries, it will be important for future studies to examine whether injury severity is modified by the frequency, recency, and type of mental health care received prior to attempt.

Our findings are cross-sectional but suggest that the risk of undetected SA may be highest toward the end of the first term of enlistment. This is in contrast to the risk for documented SA, which is highest toward the beginning of service and generally decreases as time in service increases (Ursano et al., Reference Ursano, Kessler, Stein, Naifeh, Aliaga, Fullerton and Heeringa2015b). Although this discrepancy may be due in part to the fact that the AAS survey did not include soldiers in their first 6 months of service, or to differential attrition from service, it may also indicate that willingness to disclose SAs, as well as detection of SAs, vary during different Army career and life phases. For example, the elevated risk of an undetected SA in the fourth year of service may reflect changes in family and life stressors, changes in probability of detection, and/or changes in career circumstances that affect willingness to disclose an SA, such as concern over how a SA will affect one's ability to re-enlist.

The current study has several limitations. First, the consent rate for administrative data linkage varied from a high of 90.9% to a low of 55.6% across survey samples. As with any kind of nonresponse, lower consent rates for administrative data linkage will bias results to the extent that the unadjusted determinants of non-consent are also determinants of having an undetected SA. We are unable to determine the extent to which this is the case or the effect it may have had on the representativeness of the findings, but we used best practices methods to address the issue through the propensity score weighting procedure described in the Method section. Second, the SAQ only assessed respondents’ age during the first and most recent SA. Therefore, we could not determine the timing of other attempts with respect to Army accession. Third, although respondents could report an undetected SA as having occurred at any time during their Army career, as previously noted, our survey sample did not include soldiers in their first 6 months of service, which may have resulted in an underestimation of the risk of undetected SA during that period given that early attrition from service is higher among those in psychological distress (Ireland et al., Reference Ireland, Kress and Frost2012; Larson, Highfill-McRoy, & Booth-Kewley, Reference Larson, Highfill-McRoy and Booth-Kewley2008). It is also true that during the initial months of service it may be more difficult to have an undetected SA because of the intensity of training and lack of individual time. Fourth, our cross-sectional survey did not lend itself to addressing questions about combat exposure among soldiers with an undetected SA, or whether combat exposure differs for soldiers with documented SAs v. undetected SAs. Deployment, like attrition from service, is a nonrandom event. Mental health problems are among the factors associated with decreased likelihood of deployment (Larson et al., Reference Larson, Highfill-McRoy and Booth-Kewley2008; Wilson et al., Reference Wilson, Jones, Fear, Hull, Hotopf, Wessely and Rona2009), which would influence, to an unknown degree, the likelihood that survey respondents would report both an undetected SA and combat exposure. Fifth, we do not have survey-linked administrative data prior to January 1, 2000, and therefore are unable to determine whether there is documentation of in-service SAs reported as occurring during that time, an issue that only affects the few respondents with a pre-2000 SA still serving during the 2011–2013 survey. Sixth, our data do not include access to provider notes which may have documented SAs that were not coded in respondents’ administrative medical records. Seventh, consistent with the C-SSRS, our assessment of SAs was conditional on having endorsed a history of suicide ideation, raising the possibility that the prevalence and incidence of undetected SAs would have been higher without that restriction in place. Eighth, although the U.S. military pays for treatment received at civilian medical facilities, some of the soldiers with an undetected SA may have chosen to pay out-of-pocket (or used non-military insurance) for treatment of SA-related injuries at a civilian facility, in which case the SA would not have been documented in Army/DoD administrative medical records. Nineth, SAQ responses, including information about SAs, are subject to selective reporting and recall bias. Lastly, our findings may not generalize to other populations.

Conclusions

The linkage of representative survey data and administrative medical records available in Army STARRS provides a unique opportunity to examine concordance between self-reported and medically documented SAs in active-duty soldiers. Our findings suggest that the annual incidence of SA among Regular Army enlisted soldiers is likely higher than indicated by previous studies which are based only on documented SAs (Ursano et al., Reference Ursano, Kessler, Stein, Naifeh, Aliaga, Fullerton and Heeringa2015b). Given that U.S. servicemembers have universal healthcare access, required medical examinations on at least an annual basis, and regularly complete mental health screenings, there is reason to believe that the rate of undetected SAs in the U.S. general population is substantially higher. Perhaps our findings will encourage examination of the incidence and impact of undetected SAs within other patient populations. The high prevalence of MH-Dx before undetected SAs suggests that barriers to disclosing the attempt did not preclude most of those soldiers from being identified in the mental healthcare system as needing care. Further study is needed to understand and increase help seeking before a SA. The number of undetected SAs may be reduced through interventions that promote willingness to disclose suicidal thoughts and behaviors not only to clinicians, but to partners, friends, peers, supervisors, and leaders, as well as education on how to respond and assist when someone asks for help. Additional interventions may be required to address the needs of soldiers with mental health problems who either do not perceive a need for help (Naifeh et al., Reference Naifeh, Colpe, Aliaga, Sampson, Heeringa, Stein and Kessler2016) or who feel isolated and believe they do not have close peers, family, or friends they can reach out to for support.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291724001028.

Acknowledgements

Team Acknowledgements

The Army STARRS Team consists of Co-Principal Investigators: Robert J. Ursano, MD (Uniformed Services University) and Murray B. Stein, MD, MPH (University of California San Diego and VA San Diego Healthcare System)

Site Principal Investigators: James Wagner, PhD (University of Michigan) and Ronald C. Kessler, PhD (Harvard Medical School)

Army scientific consultant/liaison: Kenneth Cox, MD, MPH (Office of the Assistant Secretary of the Army (Manpower and Reserve Affairs))

Other team members: Pablo A. Aliaga, MS (Uniformed Services University); David M. Benedek, MD (Uniformed Services University); Laura Campbell-Sills, PhD (University of California San Diego); Carol S. Fullerton, PhD (Uniformed Services University); Nancy Gebler, MA (University of Michigan); Meredith House, BA (University of Michigan); Paul E. Hurwitz, MPH (Uniformed Services University); Sonia Jain, PhD (University of California San Diego); Tzu-Cheg Kao, PhD (Uniformed Services University); Lisa Lewandowski-Romps, PhD (University of Michigan); Alex Luedtke, PhD (University of Washington and Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center); Holly Herberman Mash, PhD (Uniformed Services University); James A. Naifeh, PhD (Uniformed Services University); Matthew K. Nock, PhD (Harvard University); Nur Hani Zainal PhD (Harvard Medical School); Nancy A. Sampson, BA (Harvard Medical School); and Alan M. Zaslavsky, PhD (Harvard Medical School).

Funding statement

Army STARRS was sponsored by the Department of the Army and funded under cooperative agreement number |U01MH087981 (2009–2015) with the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH). Subsequently, STARRS-LS was sponsored and funded by the Department of Defense (USUHS grant number HU0001-15-2-0004).

Competing interests

In the past 3 years, Dr Kessler was a consultant for Datastat, Inc., Holmusk, RallyPoint Networks, Inc., and Sage Therapeutics. He has stock options in Mirah, PYM, and Roga Sciences. In the past 3 years Dr Stein received consulting income from Actelion, Acadia Pharmaceuticals, Aptinyx, atai Life Sciences, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bionomics, BioXcel Therapeutics, Clexio, EmpowerPharm, Engrail Therapeutics, GW Pharmaceuticals, Janssen, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, and Roche/Genentech. Dr Stein has stock options in Oxeia Biopharmaceuticals and EpiVario. He is paid for his editorial work on Depression and Anxiety (Editor-in-Chief), Biological Psychiatry (Deputy Editor), and UpToDate (Co-Editor-in-Chief for Psychiatry). All other authors report no financial relationships with commercial interests.

Disclaimers

The contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the NIMH, the Department of the Army, the Department of Defense, or the Department of Veteran Affairs.

The opinions and assertions expressed herein are those of the author(s) and do not reflect the official policy or position of the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences or the Department of Defense.

The contents of this publication are the sole responsibility of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views, opinions or policies of The Henry M. Jackson Foundation for the Advancement of Military Medicine, Inc. Mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government.

Ethical standards

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.