Household food insecurity or a household’s inability to provide adequate and proper nutritious food due to lack of money and resources(Reference Coleman-Jensen, Matthew and Christian1) has been identified as a national public health problem in the USA(Reference Drennen, Coleman and de Cuba2,Reference Nord3) . According to a recent 2018 report by the US Department of Agriculture, more than 37 million adults lived in food-insecure households(Reference Coleman-Jensen, Matthew and Christian1). The report also noted that 11·1 % of US households were food insecure during the past year, with 4·3 % experiencing very low food security(Reference Coleman-Jensen, Matthew and Christian1). Prevalence of household food insecurity among young children in the USA is a significant concern as the lack of nutritious food among infants, toddlers and preschoolers has been linked to developmental and behavioural problems, hospitalisation and poor health outcomes later in life(Reference Gundersen and Ziliak4–Reference Schmeer and Piperata6). Moreover, the periods of infancy, toddlerhood and preschool are critical developmental phases for brain development(Reference Dubois, Dehaene-Lambertz and Kulikova7,Reference Zhang, Shi and Wei8) . Thus, the lack of access to nutritious food during these crucial developmental phases can have adverse long-term effects on child development and overall well-being(Reference Drennen, Coleman and de Cuba2).

Although infants and young children may be disproportionately affected by household food insecurity(Reference Coleman-Jensen, Matthew and Christian1), few studies in the USA have examined household food insecurity among this population. Notably, prior studies on household food insecurity among children aged 0–5 years have been conducted abroad in countries such as Bangladesh(Reference Ahmed, Mahfuz and Ireen9), Ghana and Malawi(Reference Adams, Vosti and Ayifah10), India and Ethiopia(Reference Petrikova11), the Democratic Republic of the Congo(Reference Mukuku, Mutombo and Kamona12), Uganda(Reference Kikafunda, Agaba and Bambona13) and Mexico(Reference Sánchez-Pérez, Hernán and Ríos-González14). Prior studies from the USA have primarily examined household food insecurity among children aged 0–17 years(Reference Schmeer and Piperata6,Reference Iriart, Boursaw and Rodrigues15,Reference Jackson, Chilton and Johnson16) .

Factors such as low socioeconomic status(Reference Schmeer and Piperata6,Reference Adams, Hoffmann and Rosenberg17–Reference Johnson and Markowitz19) , racial or ethnic minority status(Reference Rose and Bodor20) and poor caregiver mental or physical health(Reference King21) have been linked to household food insecurity among children and adolescents in the USA. Findings regarding the association between receipt of welfare assistance and household food insecurity are mixed, with some studies showing cash or food assistance to be associated with a higher risk of household food insecurity(Reference King21). In contrast, others have found that receipt of cash or food assistance decreases the risk of household food insecurity(Reference Mabli and Worthington22,Reference Nord23) . The Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) is the largest federal nutrition assistance program in the USA and aims to reduce hunger and improve the health and well-being of low-income individuals and families(24). Recently, Fernald and Gosliner(Reference Fernald and Gosliner25) reviewed the literature on receipt of welfare benefits and household food insecurity and noted that although receipt of SNAP benefits was associated with lower odds of household food insecurity, more than half of households that received SNAP benefits remained food insecure. This may suggest that persistent household food insecurity may be a consequence of the most at-risk households self-selecting into SNAP benefits or that SNAP benefits are insufficient to lift households out of food insecurity(Reference Seligman and Berkowitz26).

Adverse childhood experiences (ACE), which typically include emotional, physical or sexual abuse during childhood, living with a caregiver who has a substance use disorder or mental health issues or parental divorce, among others(Reference Dube, Felitti and Dong27), have also gained the attention of researchers, policymakers and practitioners. Exposure to ACE during the first 18 years of life is known to have a long-term negative impact on child outcomes such as development(Reference Sun, Knowles and Patel28), physical health(Reference Hughes, Bellis and Hardcastle29), depression and anxiety(Reference Chapman, Whitfield and Felitti30–Reference Larkin, Felitti and Anda32), suicidal behaviours(Reference Baiden, Stewart and Fallon33), alcohol, tobacco and illicit substance use(Reference Traube, James and Zhang34) and risky sexual behaviours(Reference Dube, Felitti and Dong27,Reference Anda, Felitti and Bremner35–Reference Noll, Haralson and Butler37) .

There is a burgeoning number of studies that have found ACE to be closely linked to household food insecurity(Reference Jackson, Chilton and Johnson16,Reference Chilton, Knowles and Rabinowich38) . For instance, Jackson and colleagues(Reference Jackson, Chilton and Johnson16) examined the association between ACE and household food insecurity among children aged 0 to 17 years using data from the 2016 National Survey of Children’s Health (NSCH). They found that compared with children with no ACE, children with three or more ACE had 8·14 times higher risk of experiencing moderate-to-severe food insecurity. Previous studies with adult samples have also found social and emotional support to be a protective factor against ACE and its impact on health and mental health outcomes(Reference LaBrenz, Dell and Fong39). Yet, as with general studies on household food insecurity, little is known about the association between ACE and household food insecurity among infants and young children in the USA. A systematic review by Shanker et al.(Reference Shankar, Chung and Frank5) found only three prior studies on household food insecurity among infants and toddlers. Although two of these studies(Reference Hernandez and Jacknowitz40,Reference Zaslow, Bronte-Tinkew and Capps41) used data from the US, neither took into account the effect of ACE in understanding household food insecurity outcomes. Given the impact of both ACE and household food insecurity across the lifespan and the particular vulnerability of infants and young children to poor nutrition and health outcomes(Reference Baiden, Boateng and Dako-Gyeke42), it is important to understand this association and potential protective factors that could help build resilience.

Theoretical framework

Recent advances in developmental neurobiology have enhanced our understanding of the impact of early childhood adversity on developmental outcomes(Reference Insana, Banihashemi and Herringa43). Notably, a developmental neurobiological perspective recognises that chronic stress or chronic exposure to adversity during the first years of life can disrupt normal brain development, leading to dysregulation and asynchronous brain development(Reference Perry44). Specific to household food insecurity, deficits in nutrition during these first years of life can result in long-term negative outcomes such as behavioural abnormalities, poor learning outcomes and decreased attention span. As a result, some experts have termed the ‘first 1000 d’ as a golden age of opportunity to establish optimal nutrition(Reference Cusick and Georgieff45). Therefore, it is crucial to understand the association between ACE and household food insecurity among infants and toddlers, as well as possible risk or protective factors to better address food insecurity during the first few years of life. Such an understanding could help to provide a stable base for child development.

Objectives and hypotheses

Studies examining household food insecurity tend to rely on children of school-going age(Reference Schmeer and Piperata6,Reference Jackson, Chilton and Johnson16,Reference Huang and King18,Reference Mabli and Worthington22,Reference Howard46) , thereby masking important developmental differences in young children’s experiences of household food insecurity. This study sought to address the gap in the literature by examining the association between ACE and household food insecurity among children aged 0–5 years in the USA. Based on prior literature, we hypothesised the following: (1) there will be a positive association between ACE and household food insecurity, (2) higher socioeconomic status will decrease the risk of household food insecurity and (3) perceived parental emotional or social support will decrease the risk of household food insecurity.

Data and methods

Data source and participants

The data used in this study came from the 2016–2017 NSCH conducted by the US Census Bureau on behalf of the US Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration and Maternal and Child Health Bureau. Additional support in measuring household food insecurity among children was provided by the US Department of Agriculture. Detailed information about the NSCH, including the objectives, methodology and sampling procedure, is provided in its methodology report(47). In brief, the NSCH is a representative national survey designed to (1) estimate national and state-level prevalence for a variety of child and family health measures, (2) generate information about children, families, schools and neighbourhoods to help guide policymakers, advocates and researchers and (3) provide baseline estimates for federal and state performance measures, Healthy People 2020 objectives and state-level needs assessments. The 2016–2017 NSCH covers topics such as demographic, health and functional status, health care access and utilisation, early childhood (0–5 years) issues, issues specific to middle childhood and adolescence (6–17 years), family functioning, parental health status and family and neighbourhood and community characteristics. The 2016–2017 NSCH covered children aged 0–17 years who live in households nationally and in each state. There were a total of 71 811 (weighted n 73 387 211) children and adolescents in the 2016–2017 NSCH. The overall weighted response rate was 40·7 % for 2016 and 37·4 % for 2017. The analyses presented in this study are restricted to children aged 0–5 years with valid data on the outcome and explanatory variables. This resulted in an analytic sample size of 17 543. The 2016–2017 NSCH data have been de-identified and are publicly available; hence, no institutional review board approval was required.

Variables

Outcome variable

The outcome variable investigated in this study was household food insecurity and was measured as a nominal variable. In the 2016–2017 NSCH, primary caregivers were asked: which of these statements best describes the food situation in your household in the past 12 months? With the following response options ‘1 = we could always afford to eat good nutritious meals’, ‘2 = we could always afford enough to eat but not always the kinds of food we should eat’, ‘3 = sometimes we could not afford enough to eat’ and ‘4 = often we could not afford enough to eat’. Following the recommendation of past studies(Reference Jackson, Chilton and Johnson16,Reference Bocquier, Vieux and Lioret48–Reference Leung, Williams and Villamor51) , respondents who indicated that they could sometimes or often not afford enough to eat were considered as experiencing moderate-to-severe food insecurity and were coded as 2. Respondents who indicated that they could always afford enough to eat but not always the kinds of nutritious food were considered as experiencing mild food insecurity and were coded as 1. Respondents who indicated that they could always afford to eat good nutritious meals were considered food secure and were coded 0. The item used in measuring household food insecurity in this study was closely related to the 18-item Household Food Security Survey Module developed by the US Department of Agriculture(Reference Leung and Villamor50–Reference Alaimo, Olson and Frongillo52).

Explanatory variable

The main explanatory variable examined in this study was ACE score. The ACE measure was based solely on primary caregiver reports. Primary caregivers were asked ‘to the best of your knowledge, has this child EVER experienced any of the following?’: (1) a parent or caregiver divorced or separated, (2) a parent or caregiver died, (3) a parent or caregiver served time in jail, (4) saw or heard parents or adults slap, hit, kick punch one another in the home, (5) was a victim of violence or witnessed violence in the neighbourhood, (6) lived with anyone who was mentally ill, suicidal or severely depressed, (7) lived with anyone who had a problem with alcohol or drugs and (8) treated or judged unfairly due to race/ethnicity. Primary caregivers were asked to indicate yes = 1 if the child ever experienced this form of adversity and no = 0 if the child had not experienced this form of adversity. These measures of ACE have been used in previous studies to understand the link between ACE and maternal and child health outcomes(Reference Jackson, Chilton and Johnson16,Reference Crouch, Radcliff and Hung53,Reference LaBrenz, Panisch and Lawson54) . A count measure of ACE score was then created by summing each item to arrive at the total number of ACE experienced. Scores ranged from 0 to 8, with higher scores indicating more ACE. Due to the non-normal distribution of scores on ACE, scores of 2 or more were combined into one category and treated as an ordinal variable in the analysis (0, 1 and ≥2).

Other covariates examined in this study included primary caregiver’s level of education, poverty level, receipt of cash or food assistance, emotional support, self-rated physical health of the primary caregiver and mental/emotional health of the primary caregiver. Primary caregiver’s level of education was coded into ‘0 = High school or less’, ‘1 = Some college or technical school’ and ‘2 = College degree or higher’. Household poverty/income level was measured based on the federal poverty level (FPL) and was coded into the following categories ‘0 = 0–99 % FPL’, ‘1 = 100–199 % FPL’ ‘2 = 200–399 % FPL’ and ‘3 = 400 % or above FPL’. Receipt of food or cash assistance was measured as a composite measure based on responses to the following four survey items that ask about whether someone in the child’s family received: (1) benefits from the Woman, Infants, and Children (WIC) Program, (2) cash assistance from government welfare programme, (3) Food Stamps or SNAP benefits or (4) free or reduced-cost breakfasts or lunches at school during the past 12 months. Primary caregiver’s physical health status was coded into ‘0 = good’ v. ‘1 = poor’. Similarly, primary caregiver’s mental/emotional health status was coded into ‘0 = good’ v. ‘1 = poor’. Lastly, a measure of caregiver emotional support was included as a binary variable. Respondents who answered yes to the question ‘During the past 12 months, was there someone that you could turn to for day-to-day emotional support with parenting or raising children?’ were coded 1; otherwise, they were coded 0.

Demographic variables

The study controlled for the following demographic variables, age of child and caregiver, sex of child, immigration status of child and race/ethnicity. Both child’s age and caregivers age were measured in years as a continuous variable. Sex of child was coded as ‘0 = male’ and ‘1 = female’. Children born in the USA were coded 0, whereas children born outside the US were coded 1. Lastly, race/ethnicity as coded into ‘0 = non-Hispanic White’, ‘1 = non-Hispanic Black’, ‘2 = Hispanic’ and ‘3 = Other race/ethnicity’.

Data analyses

Data were analysed using descriptive, bivariate and multivariate analytic techniques. First, the general distribution of all the variables included in the analysis was examined using percentages for categorical variables and mean and sd for continuous variables. Second, bivariate associations between household food insecurity and the categorical variables were examined using Pearson χ 2 test of association. The main analysis involved the use of multinomial logistic regression to examine the association between ACE and household food insecurity while controlling for the effects of child and caregiver/parent’s characteristics and other covariates. We opted for multinomial logistic regression, given that the outcome variable (household food insecurity) was measured as a nominal variable with more than two categories (i.e. food-secure, mild food insecurity and moderate-to-severe food insecurity). Relative risk ratios (RRR) were reported together with their 95 % CI. Variables were considered significant if the P value was <0·05. Stata’s ‘svy’ command was used to account for the weighting and complex survey design employed by the NSCH. All analyses were performed using Stata version 14.

Results

Distribution of adverse childhood experiences

Table 1 shows the general distribution of ACE. Of the 17 543 respondents, 83·7 % experienced no ACE, 11·3 % experienced one ACE and 5 % experienced two or more ACE. The most prevalent types of ACE were parental separation/divorce (9·3 %), living with someone who was mentally ill, suicidal or severely depressed (4 %), living with someone who had a problem with alcohol or drugs (3·5 %) and having a parent or guardian who had served time in jail (2·8 %). The prevalence of other types of ACE was less than 2 %.

Table 1 Distribution of adverse childhood experiences (ACE) (n 17 543)

Sample characteristics

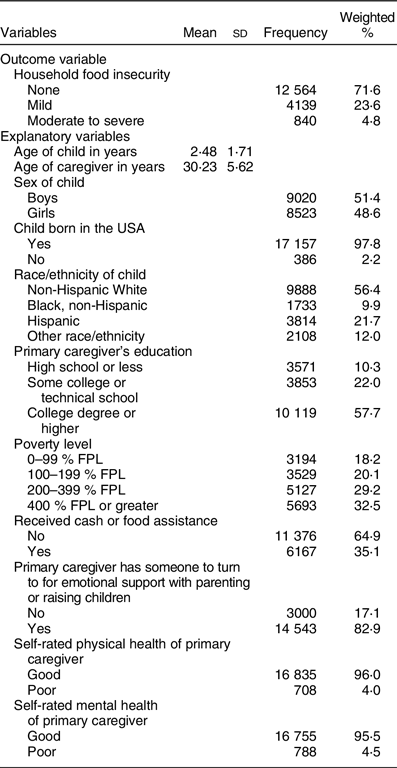

Table 2 shows the general distribution of the variables examined in this study. About one in twenty (4·8 %) children experienced moderate-to-severe food insecurity, 23·6 % experienced mild food insecurity and 71·6 % were food secure. The average age of children in this sample was 2·48 (sd 1·71 years), and the average age of caregivers was 30·23 (sd 5·62 years). Slighty more than half of the children were boys (51·4 %) and <3 % were born outside the USA. More than half (56·4 %) of the children were non-Hispanic White, 9·9 % were non-Hispanic Black, 21·7 % were Hispanic and 12 % identified as ‘Other’ race/ethnicity. Regarding caregivers, most had a college degree or higher (57·7 %), 22 % had some college or technical education and 10·3 % had high school or less education. With respect to poverty level, 18·2 % of children lived in households with income below the federal poverty level. More than a third of the children (35·1 %) lived in households that received cash or food assistance. About five in six caregivers (82·9 %) had someone to turn to for emotional support with parenting or raising children. A little over 4 % of caregivers rated their mental/emotional health to be poor and 4 % rated their physical health to be poor.

Table 2 Sample characteristics (n 17 543)

FPL, federal poverty level.

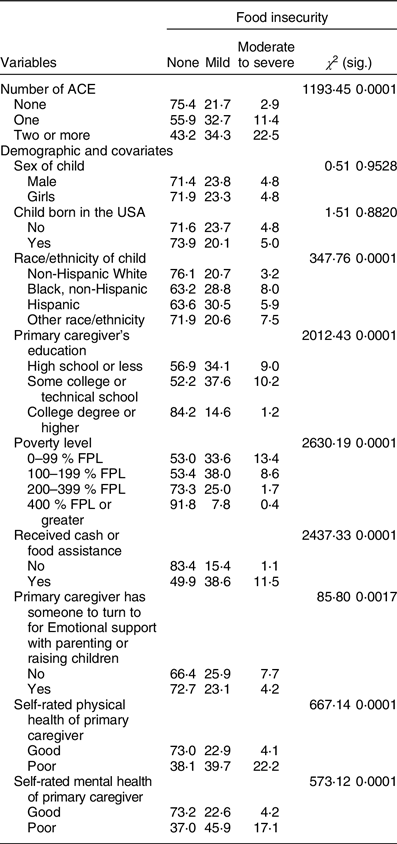

Bivariate association between food insecurity and categorical variables

As shown in Table 3, a significant bivariate association was observed between household food insecurity and a number of categorical variables. About one in four children (22·5 %) who had two or more ACE compared with 11·4 % of children who had one ACE, and 2·9 % of children who had no ACE experienced moderate-to-severe food insecurity (χ 2(4) = 1193·45, P < 0·0001). One in ten children whose primary caregivers had some college or technical education compared with 9 % of children whose primary caregivers had high school or less education, and 1·2 % of children whose primary caregivers had college education of higher experienced moderate-to-severe food insecurity (χ 2(4) = 2012·43, P < 0·0001). Poverty level was inversely associated with household food insecurity (χ 2(6) = 2630·19, P < 0·0001). The proportion of children that experienced moderate-to-severe food insecurity was greater if their primary caregiver received cash/food assistance or had poor physical, mental or emotional health. Children whose primary caregivers had someone they could turn to for emotional support with parenting or raising children were less likely to experience moderate-to-severe food insecurity.

Table 3 Bivariate association between food insecurity and categorical variables (n 17 543)

ACE, adverse childhood experiences; FPL, federal poverty level.

Multinomial logistic regression examining the association between adverse childhood experience and household food insecurity

Table 4 shows the multinomial logistic regression results examining the association between ACE and household food insecurity while adjusting for the effects of other factors. Compared with children with no ACE, among children with two or more ACE, the risk of mild food insecurity was 1·5 times higher (RRR = 1·50, P < 0·001, 95 % CI 1·24, 1·81), and the risk of moderate-to-severe food insecurity was nearly four times higher (RRR = 3·96, P < 0·001, 95 % CI 3·01, 5·20) both when compared with children who were food secure. Among children with one ACE, the risk of mild food insecurity was 1·43 times higher (RRR = 1·43, P < 0·001, 95 % CI 1·25, 1·63), and the risk of moderate-to-severe food insecurity was 2·33 times higher (RRR = 2·33, P < 0·001, 95 % CI 1·84, 2·95) both when compared with children who were food secure. Each additional year increase in caregiver’s age decreased the risk of mild food insecurity (RRR = 0·98, P < 0·001, 95 % CI 0·97, 0·98) and moderate-to-severe food insecurity (RRR = 0·98, P < 0·05, 95 % CI 0·96, 1·00) by a factor of 2 %. The risk of moderate-to-severe food insecurity was higher among children with primary caregivers who had some college or technical school education (RRR = 1·38, P < 0·01, 95 % CI 1·10, 1·74), received food or cash assistance (RRR = 5·47, P < 0·001, 95 % CI 4·29, 6·99), perceived their physical health (RRR = 3·08, P < 0·001, 95 % CI 2·24, 4·24) or mental health to be poor (RRR = 3·09, P < 0·001, 95 % CI 2·28, 4·19). A similar pattern of results was obtained when comparing mild food insecure households to food-secure households. However, the risk of moderate-to-severe food insecurity was lower for children with a primary caregiver who had a college degree or higher, living in high-income households or with a primary caregiver who had someone to turn to for emotional support with parenting or raising children.

Table 4 Multinomial logistic regression results predicting food insecurity among children under 5 (n 17 543)

RRR, relative risk ratios; FPL, federal poverty level; ACE, adverse childhood experiences.

Model pseudo R square = 0.1909.

Discussion

This study examined the association between ACE and household food insecurity among a nationally representative sample of children aged 0–5 years. Approximately 4·8 % of children experienced moderate-to-severe household food insecurity and 23·6 % experienced mild food insecurity, while 35·1 % received cash or food assistance. The finding that 4·8 % of children aged 0–5 years experienced moderate-to-severe food insecurity is consistent with a national report by Coleman-Jensen et al.(Reference Coleman-Jensen, Matthew and Christian1) who found that 4·3 % of US households experienced very low food insecurity in 2018. Consistent with prior literature on older individuals(Reference Jackson, Chilton and Johnson16,Reference Sun, Knowles and Patel28) , ACE were associated with household food insecurity. Notably, children with one ACE had greater risk of mild food insecurity and moderate-to-severe food insecurity when compared with children with no ACE. Moreover, the risk of mild food insecurity among children with two or more ACE was 2·33 times higher and that of moderate-to-severe food insecurity was 3·96 times higher when compared with children with no ACE. Indeed, the strength of the association between ACE and household food insecurity among children ages 0–5 years might indicates a particularly detrimental impact of adversity exposure for this population. Also consistent with prior literature(Reference Schmeer and Piperata6) and our second hypothesis, higher socioeconomic status was negatively associated with household food insecurity. Contrary to prior findings(Reference Rose and Bodor20), this study found no association between child demographic characteristics and household food insecurity.

After adjusting for the effect of ACE and socioeconomic factors, receipt of cash or food assistance, parental emotional support and parental physical or mental health were linked to household food insecurity. It is possible recipients of food or cash assistance may have higher rates of food insecurity prior to program enrollment. Prior research has found that up to 56·5 % of households classified as having low food security participate in cash or food assistance programmes(Reference Coleman-Jensen, Matthew and Christian1). Notably, outcomes associated with ACE in prior literature, such as poor parental mental and physical health, were also indicative of food insecurity. This is consistent with previous research among samples of older children(Reference King21).

Results from this study also supported our third hypothesis that parental emotional support would be negatively associated with food insecurity. Prior literature has also found social or emotional support to be a protective factor against ACE and their impact(Reference LaBrenz, Panisch and Lawson54). Thus, providers that work with families of young children might utilise interventions that increase social and emotional support networks to build protective factors and resilience, especially among those at-risk of ACE exposure.

Limitations

There are some limitations to this study. First, the data are cross-sectional; hence, causality cannot be established; only an association can be concluded. It is possible that some children may have experienced household food insecurity before they experience childhood adversity. It is also possible that the experience of household food insecurity could lead to certain types of adversities, such as family violence(Reference Jackson, Lynch and Helton55). A study that followed infants and toddlers would help establish the link between ACE and household food insecurity and determine whether there is a bi-directional association between ACE and household food insecurity among children aged 0–5 years. Second, given the young age of children in this sample, it is likely that ACE score might increase as they age. As a result, ACE score was grouped as 0, 1 and 2+, given that children aged 0–5 years had not had as much time to potentially be exposed to adverse experiences. Third, we were unable to determine the duration of household food insecurity. This is an important avenue for future research. Finally, while prior literature focused largely on the impact of household food insecurity on future outcomes, the cross-sectional nature of the data did not permit the research team to observe the long-term impacts of household food insecurity or food security as a possible moderator between ACE and other long-term outcomes such as externalising behaviours, internalising behaviours, physical health problems or health risk behaviours.

Conclusion

ACE were found to be associated with household food insecurity for children aged 0–5 years. Given the critical period of development during the first few years of life, it is crucial to prevent ACE and household food insecurity, as well as provide early intervention in cases of adversity exposure. This can help to mitigate the negative impact of ACE and food insecurity on child development. Consistent with prior literature that has found social support to mitigate the impact of ACE on long-term outcomes(Reference Von Cheong, Sinnott and Dahly56), the findings of this study suggest that social support may also be a protective factor against household food insecurity. Therefore, future research could examine specific early interventions to build social and emotional support networks among families with young children who are at-risk for ACE or household food insecurity. Additionally, future studies could quantitatively examine the association between ACE across the life course to include generational patterns on current household food insecurity. A recent qualitative study found intergenerational disadvantage and adversities were linked to household food insecurity for at least three generations(Reference Chilton, Knowles and Bloom57). Such an investigation could shed light on needed long-term support efforts from public assistance programmes such as SNAP to address generational family adversity and food insecurity. Furthermore, future research could longitudinally examine the impact of food or cash assistance programmes on household food insecurity over time. This could allow researchers to better understand the long-term implications and benefits of food and cash assistance among low-income families.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: This paper is based on public data from the National Survey of Children’s Health (NSCH) conducted by the US Census Bureau on behalf of the US Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration and Maternal and Child Health Bureau. The views and opinions expressed in this paper are those of the authors. Dr. Baiden had full access to all of the data and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Financial support: None. Conflict of interest: None. Authorship: P.B conceived of the initial idea, designed the study, analysed, interpreted the findings and wrote the first draft of the manuscript; C.L. contributed to the interpretation of the data and wrote part of the discussion; S.T. contributed to writing the literature review and wrote part of the discussion; G.A. contributed to writing the literature review and wrote part of the discussion and B.H. contributed to writing part of the discussion. All authors contributed significantly to the interpretation of the findings, the writing of the manuscript and approval of the final version. Ethics of human subject participation: Data for this study have been de-identified and are publicly available; hence, no institutional review board approval was required.