The WHO and UNICEF define timely initiation of breast-feeding (TIBF) as putting a newborn to breast within 1 h of birth and exclusive breast-feeding (EBF) as feeding infants only human milk through breast-feeding or expressed breast milk and no other liquids or solids, except for drops or syrups with nutritional supplements or medicine( 1 ). All infants should receive human milk within the first hour of birth, be exclusively breast-fed for the first 6 months and thereafter be introduced to nutritionally adequate and safe complementary foods with continued breast-feeding for at least 2 years( 2 , 3 ). Breast-feeding is one of the most cost-effective interventions that prevents maternal and newborn morbidity and mortality( 4 – Reference Patel, Bansal and Nimbalkar 7 ). For example, TIBF and EBF prevent 22 and 60 % of neonatal deaths, respectively( 2 , Reference Edmond, Zandoh and Quigley 8 , 9 ). Furthermore, EBF for a longer duration benefits child neurodevelopment and increases intelligence quotient( Reference Belfort 10 ).

Despite the aforementioned advantages, significantly low percentages of mothers initiate breast-feeding within the first hour of birth and maintain EBF for 6 months. Globally, 44 and 40 % of newborns are breast-fed within the first hour and breast-feed exclusively for 6 months, respectively( 4 , 11 ). In developing countries, the prevalence of TIBF ranges from 22·4 to 52·8 %( Reference Kitano, Nomura and Kido 12 – Reference Lande, Andersen and Baerug 18 ) and EBF prevalence ranges from 10·0 to 49·1 %( 11 , Reference Kitano, Nomura and Kido 12 , Reference Ludvigsson and Ludvigsson 13 , Reference Dennis 19 , Reference Hruschka, Sellen and Stein 20 ). In Ethiopia, based on our previous meta-analyses( Reference Habtewold, Mohammed and Endalamaw 21 ), the national prevalence of TIBF and EBF is 66·5 and 60·1 %, respectively.

Previous studies have identified several associated factors of TIBF and EBF, including maternal/caregiver’s age, newborn age and colostrum discarding( Reference Kitano, Nomura and Kido 12 – Reference Lande, Andersen and Baerug 18 , Reference Fisher, Hammarberg and Wynter 22 – Reference Kaneko, Kaneita and Yokoyama 25 ). Previous studies show that infant age and colostrum discarding have been associated with late initiation of breast-feeding and non-exclusive breast-feeding( Reference Senarath, Dibley and Agho 14 , Reference Victor, Baines and Agho 16 , Reference Nyanga, Musita and Otieno 26 – Reference Legesse, Demena and Mesfin 28 ). Regarding maternal/caregiver’s age, most of the reviewed literature reveals that older mothers practise TIBF( Reference Tarrant, Younger and Sheridan-Pereira 15 , Reference Victor, Baines and Agho 16 , Reference Dennis 19 , Reference Esteves, Daumas and Oliveira 24 ) and EBF( Reference Ludvigsson and Ludvigsson 13 , Reference Lande, Andersen and Baerug 18 , Reference Hruschka, Sellen and Stein 20 , Reference Fisher, Hammarberg and Wynter 22 , Reference Chye, Zain and Lim 29 ) at higher rates than young mothers, although the age cut-off value varies between studies. Another study( Reference Amin, Hablas and Al Qader 23 ) which measured age as a continuous variable also concluded that increased maternal age is positively associated with TIBF and EBF. On the contrary, some studies showed that increased maternal age was associated with delayed initiation of breast-feeding and non-exclusive breast-feeding( Reference Kitano, Nomura and Kido 12 , Reference Kaneko, Kaneita and Yokoyama 25 ). Furthermore, other studies showed absence of an association( Reference Meinzen-Derr, Guerrero and Altaye 17 , Reference Koosha, Hashemifesharaki and Mousavinasab 30 ). Taken together, inconsistencies persist and the association is inconclusive.

Hence, there is an urgent need to synthesize individual studies’ data to make a better conclusion on the association of maternal age, infant age and colostrum discarding with breast-feeding practice (i.e. TIBF and EBF). So far, several systematic reviews and meta-analyses have been conducted on TIBF and EBF( Reference Senarath, Dibley and Agho 14 , Reference Victor, Baines and Agho 16 , Reference Esteves, Daumas and Oliveira 24 , Reference Scott and Binns 31 – Reference Alebel, Dejenu and Mullu 33 ). In Ethiopia, there is a paucity of systematic review and meta-analysis with regard to associated factors of TIBF and EBF. The present meta-analyses and systematic review aimed to determine whether maternal/caregiver’s age, infant age and colostrum discharging affect TIBF and EBF in Ethiopia. We hypothesized that: (i) increased maternal age would be positively associated with breast-feeding practice due to accumulated experience; (ii) increased infant age would be negatively associated with EBF; and (iii) colostrum discarding would be negatively associated with breast-feeding practice.

Following international recommendations( 2 ), the Ethiopian Government has taken steps to improve infant and young child feeding practices. Several national nutritional strategies( 34 ), guidelines( 35 ) and nutrition programmes( 36 , 37 ) have been developed by Ministry of Health of Ethiopia since 2004. Likewise, the Health Sector Transformation Plan of Ethiopia( 38 ) has a target to increase EBF to 72 % by 2020. Furthermore, Ethiopia has recently started celebrating World Breastfeeding Week every year( 39 ). However, TIBF and EBF coverages are still below the very good rating of WHO, which is 90 % or above( 40 ). This can be attributed to several factors including colostrum discarding. It is also linked to infant as well as maternal/caregiver’s age( Reference Ludvigsson and Ludvigsson 13 – Reference Victor, Baines and Agho 16 , Reference Lande, Andersen and Baerug 18 – Reference Hruschka, Sellen and Stein 20 , Reference Fisher, Hammarberg and Wynter 22 – Reference Esteves, Daumas and Oliveira 24 , Reference Nyanga, Musita and Otieno 26 – Reference Chye, Zain and Lim 29 ). This meta-analysis information could be valuable to provide updated evidence to develop national guidelines and strategies, including on colostrum discarding.

Methods

Protocol registration and publication

The protocol has been registered with the University of York Centre for Reviews and Dissemination’s international prospective register of systematic reviews (PROSPERO; http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/display_record.asp?ID=CRD42017056768) and published( Reference Habtewold, Islam and Sharew 41 ).

Data source and search strategy

For all available publications, systematic searchs of PubMed, SCOPUS, EMBASE, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), Web of Science and WHO Global Health Library electronic databases was done. In addition, bibliographies of identified articles and grey literatures were hand-searched. A comprehensive search strategy was developed for each database in consultation with a medical information specialist (see online supplementary material, Supplemental File 1).

Eligibility criteria

All observational studies (cross-sectional, case–control, cohort, survey and surveillance reports) conducted in Ethiopia, published in English from 2000 to January 2018, were included. This period was selected because population demography changes over time and we wanted to include the latest evidences in the country. In addition, most of the published studies on the topic were conducted in this period. However, studies on preterm infants, infants in a neonatal intensive care unit or a special care baby unit, and low-birth-weight infants were excluded. Mothers or infants with HIV/AIDS were also excluded because health-care workers provide breast-feeding counselling and related interventions due to WHO recommendations on HIV and infant feeding. Consequently, the level of EBF in mothers or infants with HIV/AIDS may be higher and the associated factors may not be the same as those of HIV-uninfected mothers. Further, commentaries, anonymous reports, letters, duplicate studies, editorials, qualitative studies and citations without full text were excluded.

Study screening and selection

All studies obtained from databases and manual search were exported to EndNote citation manager. The title and abstract of all studies were screened by two reviewers (S.M.A. and T.D.H.) independently. Agreement between the reviewers, as measured by Cohen’s κ, was 0·76. Any disagreement was resolved by discussion. When consensus could not be reached, a third reviewer, who also had expertise in this area, approved the final list of retained studies. A full-text review was performed by two independent investigators (S.M.A. and T.D.H.).

Quality assessment and data extraction

The Newcastle–Ottawa Scale, which has good inter-rater reliability and validity, was used to assess the quality of studies and for potential publication bias( Reference Hartling, Hamm and Milne 42 , Reference Hootman, Driban and Sitler 43 ). The Newcastle–Ottawa Scale includes three categorical criteria with a maximum score of 9: a maximum of four stars are allotted for ‘selection’; a maximum of two stars are allotted for ‘comparability’; and a maximum of three stars are allotted for ‘outcome’. The quality of each study was rated using the following scoring algorithm: ≥7, ‘good’; 2–6, ‘fair’; and ≤1, ‘poor’( Reference McPheeters, Kripalani and Peterson 44 ). Only studies of ‘good’ quality were selected for the final review and analysis.

In addition, to define outcome measurements, the WHO infant and young child feeding practice guideline was strictly followed. TIBF was assessed by ‘since birth’, while EBF was assessed in one of the following ways: 24 h recall/seven repeated 24 h recalls/6-month recalling method/7 d self-recall/since birth dietary recall method. Based on previous systematic review reports( Reference Esteves, Daumas and Oliveira 24 , Reference Boccolini, Carvalho and Oliveira 45 , Reference Sharma and Byrne 46 ), maternal/caregiver’s age was dichotomized as ≥25 v. <25 years old whereas infant age was dichotomized as ≤3 v. 3–6 months. The Joanna Briggs Institute tool( Reference Munn, Tufanaru and Aromataris 47 ) was used to extract the following data: study area (region and place), method (design), population, number of mothers (calculated sample size and participated in actual study) and cross-tabulated data. Geographic regions were categorized based on the current Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia administrative structure. Discrepancies were resolved by consensus and cross-checking with the full text.

Statistical analysis

A weighted inverse-variance random-effects model meta-analyses was implemented. In addition, to illustrate the trend of evidence regarding the effect of newborn gender, antenatal clinic and postnatal clinic attendance on breast-feeding practices, a cumulative meta-analysis was done. Publication bias was assessed by visual inspection of the funnel plot and Egger’s regression test for funnel plot asymmetry using se as a predictor in a mixed-effects meta-regression model at P value threshold of ≤0·01( Reference Egger, Smith and Schneider 48 ). The Duval and Tweedie trim-and-fill method( Reference Duval and Tweedie 49 ) was used if we found an asymmetric funnel plot, which indicates publication bias. Cochran’s Q χ 2 test, τ 2 and I 2 statistics were used to test for heterogeneity, estimate the amount of total/residual heterogeneity and measure the variability attributed to heterogeneity, respectively( Reference Higgins and Thompson 50 ); for the current meta-analysis, we used a reference value of I 2>80 % to indicate substantial variability related to heterogeneity( Reference Habtewold, Islam and Sharew 41 ). Mixed-effects meta-regression analysis was done to identify possible sources of between-study heterogeneity. The data were analysed using ‘metaphor’ packages in R software version 3.2.1 for Windows( Reference Viechtbauer 51 ).

Data synthesis and reporting

We analysed the data in two groups of outcome measurements: TIBF and EBF. Results for each variable are shown using forest plots. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guideline was strictly followed (see online supplementary material, Supplemental File 2).

Minor changes from the published protocol

Before analysis was done, we made the following changes to our methods from the published protocol( Reference Habtewold, Islam and Sharew 41 ). We added the Joanna Briggs Institute tool( Reference Munn, Tufanaru and Aromataris 47 ) to extract the data. In addition, we used the Duval and Tweedie trim-and-fill method( Reference Duval and Tweedie 49 ) to manage publication bias. Furthermore, cumulative meta-analysis and mixed-effects meta-regression analysis were done to reveal the trend of evidence on each associated factor and to identify possible sources of between-study heterogeneity, respectively.

Result

Search results

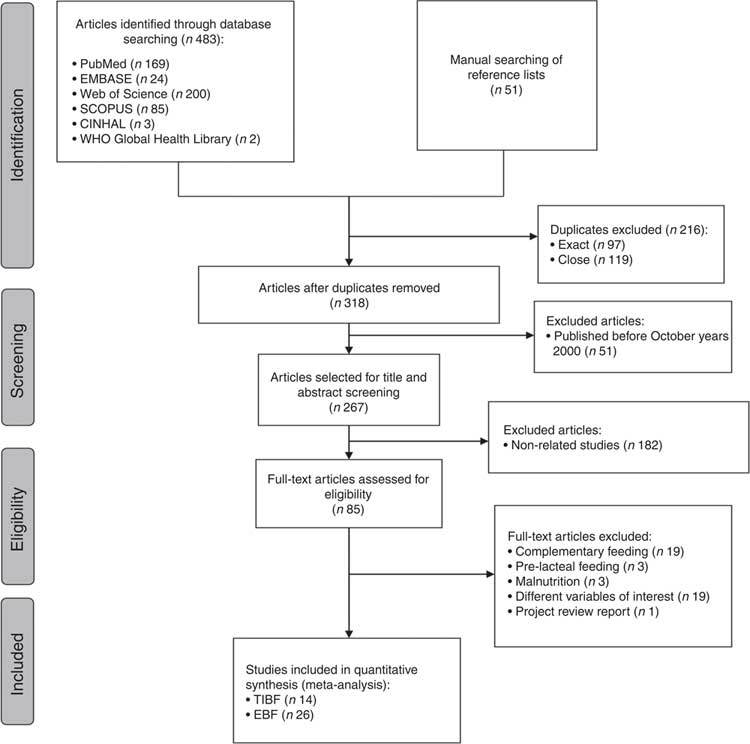

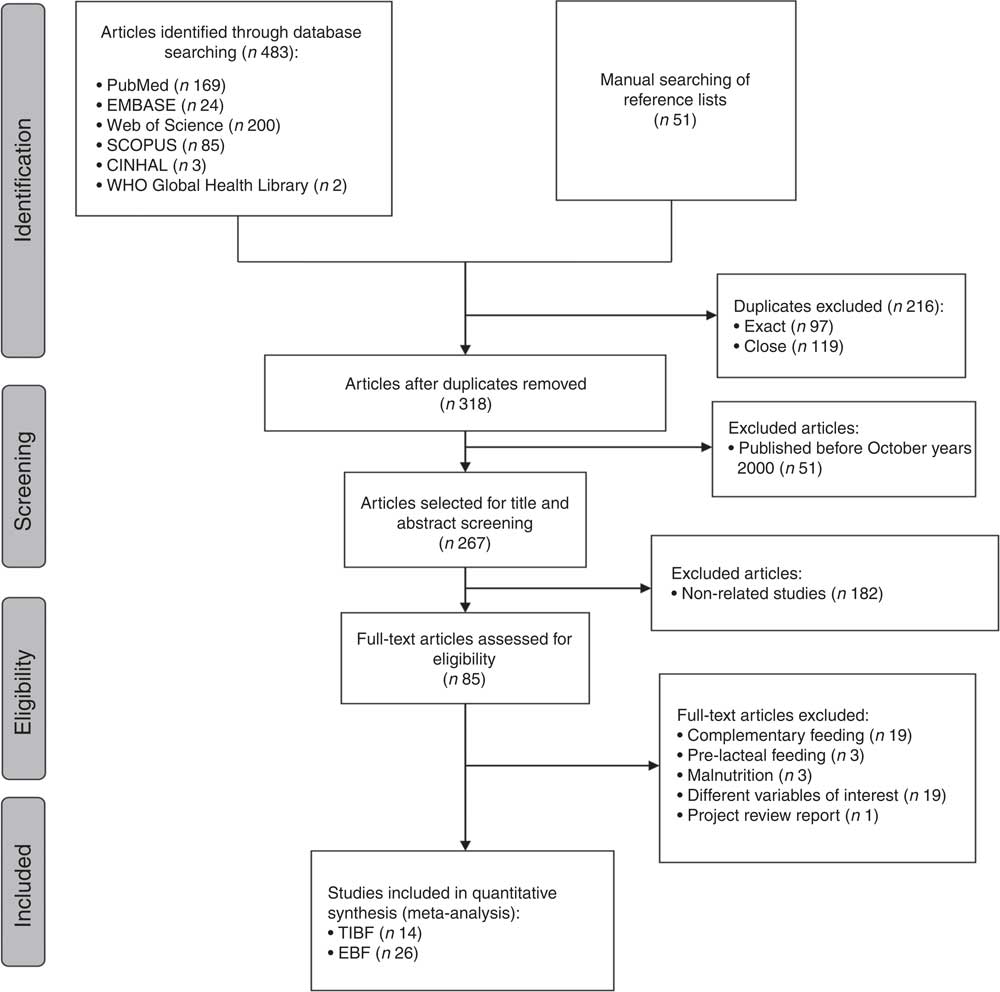

We obtained 169 articles from PubMed, twenty-four from EMBASE, 200 from Web of Science, eighty-five from SCOPUS and five from other (CINHAL and WHO Global Health Library) electronic database searching. Fifty-one additional articles were found through a manual search of reference lists of included articles. After removing duplicates and screening of titles and abstracts, the full texts of eighty-five studies were reviewed to assess eligibility. Forty-five articles were excluded after a full-text review due to several reasons: nineteen studies on complementary feeding, three on pre-lacteal feeding, three on malnutrition, nineteen with different variables of interest and one project review report. As a result, forty articles (i.e. fourteen studies on TIBF and twenty-six on EBF) fulfilled the inclusion criteria and were included in the meta-analyses. The PRISMA flow diagram of the literature screening and selection process is shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1 Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram of the literature screening and selection process for studies included in the present systematic review and meta-analysis on factors affecting timely initiation of breast-feeding (TIBF) and exclusive breast-feeding (EBF) in Ethiopia. Note ‘n’ in each stage represents the total number of studies that fulfilled a particular criterion

Study characteristics

Of the fourteen studies on TIBF, most were conducted in the Southern Nations, Nationalities and Peoples’ Region (SNNPR) and Oromia region. Regarding maternal/caregiver’s residence, six of the studies were conducted among urban dwellers (Table 1).

Table 1 Characteristics of studies included in the present systematic review and meta-analysis on factors affecting timely initiation of breast-feeding (TIBF) in Ethiopia

SNNPR, Southern Nations, Nationalities and Peoples’ Region.

The majority of the twenty-six studies on EBF were done in Amhara and SNNPR regions with eight and seven studies, respectively. Furthermore, two studies used nationally representative data of the Ethiopian Demographic and Health Survey (EDHS). Likewise, nearly half of the studies were conducted in urban residents (Table 2).

Table 2 Characteristics of studies included in the present systematic review and meta-analysis on factors affecting exclusive breast-feeding (EBF) in Ethiopia

SNNPR, Southern Nations, Nationalities and Peoples’ Region; EDHS, Ethiopian Demographic and Health Survey.

Timely initiation of breast-feeding

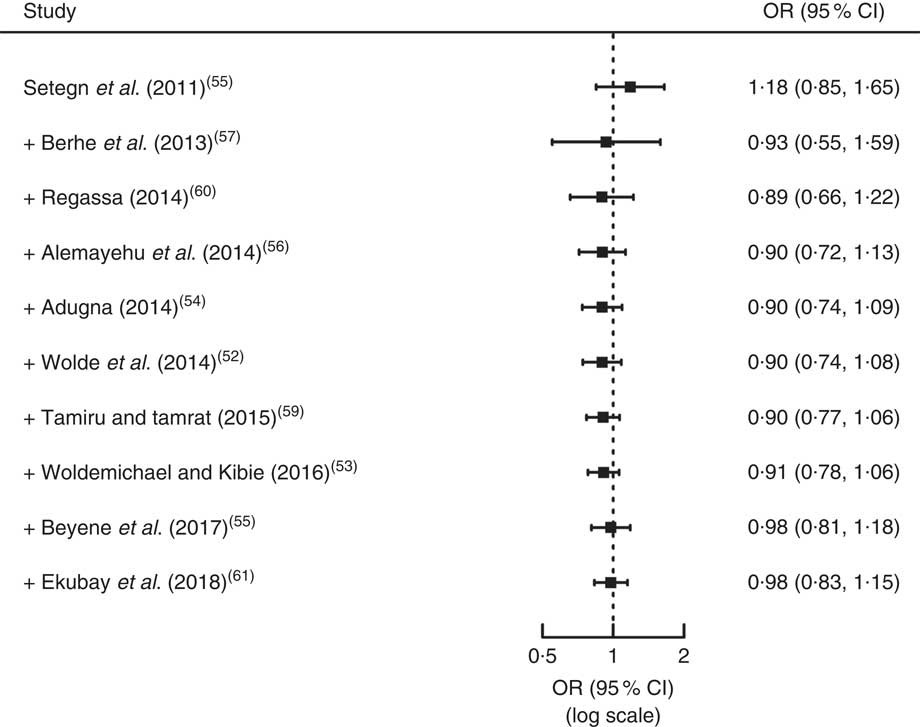

Among the fourteen studies, ten studies( Reference Wolde, Birhanu and Ejeta 52 – Reference Ekubay, Berhe and Yisma 61 ) reported the association between TIBF and maternal/caregiver’s age in 4963 mothers. The pooled OR of maternal/caregiver’s age was 0·98 (95 % CI 0·83, 1·15, P=0·78; Fig. 2). Although not statistically significant, mothers aged ≥25 years had 2 % lower chance of initiating breast-feeding within 1 h of birth compared with their younger counterparts. Egger’s regression test for funnel plot asymmetry was not significant (z=−0·40, P=0·69; see online supplementary material, Supplemental Fig. 1).

Fig. 2 Forest plot of ten studies on the association of maternal/caregiver’s age with timely initiation of breast-feeding (TIBF) in Ethiopia. The study-specific OR and 95 % CI are represented by the black square and horizontal line, respectively, with area of the square proportional to the specific-study weight to the overall meta-analysis. The centre of the black diamond represents the pooled OR and its width represents the pooled 95 % CI (LIBF, late initiation of breast-feeding; REM, random-effects model)

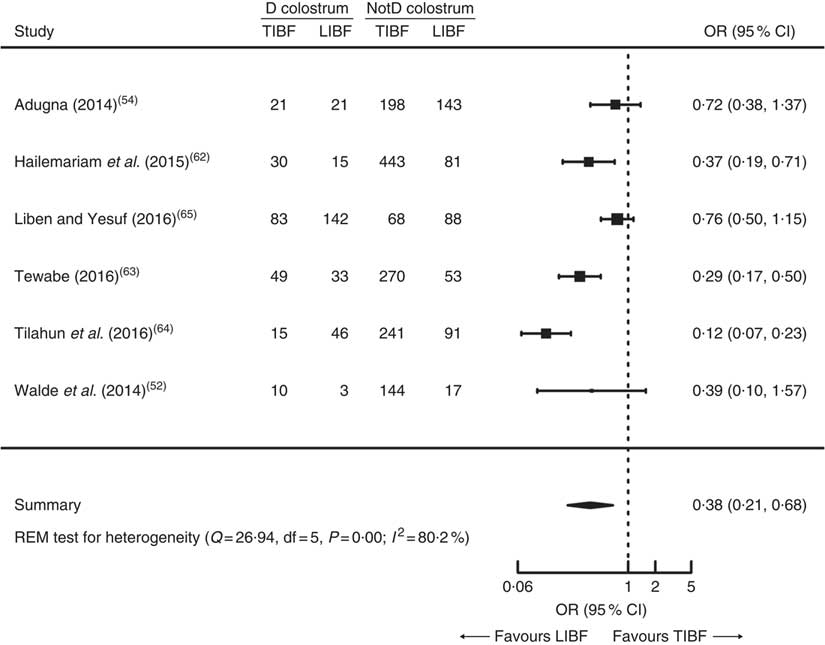

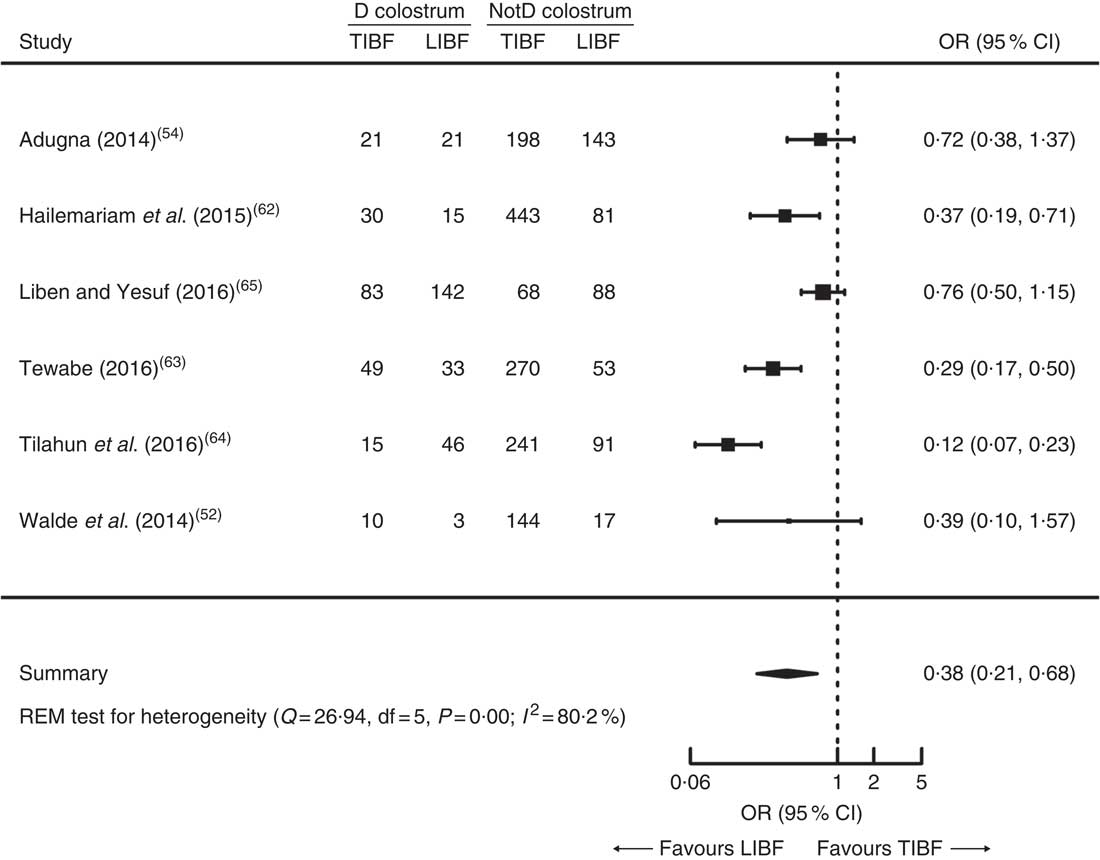

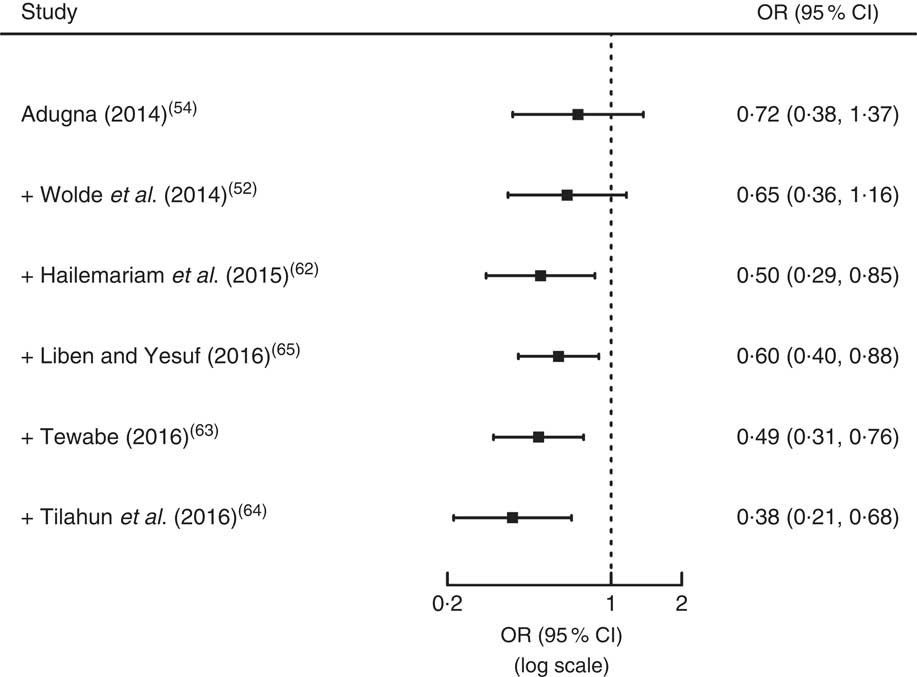

Likewise, six out of fourteen studies reported the association between TIBF and colostrum discarding in 2305 mothers( Reference Wolde, Birhanu and Ejeta 52 , Reference Adugna 54 , Reference Hailemariam, Adeba and Sufa 62 – Reference Liben and Yesuf 65 ). The pooled OR of colostrum discarding was found to be 0·38 (95 % CI 0·21, 0·68, P=0·001; Fig. 3). Compared with mothers who feed colostrum, mothers who discard colostrum had 62 % significantly lower chance of initiating breast-feeding within 1 h. Egger’s regression test for funnel plot asymmetry was not significant (z=−0·24, P=0·81; see online supplementary material, Supplemental Fig. 2).

Fig. 3 Forest plot of six studies on the association of colostrum discarding with timely initiation of breast-feeding (TIBF) in Ethiopia. The study-specific OR and 95 % CI are represented by the black square and horizontal line, respectively, with area of the square proportional to the specific-study weight to the overall meta-analysis. The centre of the black diamond represents the pooled OR and its width represents the pooled 95 % CI (D, discarding; NotD, not discarding; LIBF, late initiation of breast-feeding; REM, random-effects model)

Exclusive breast-feeding

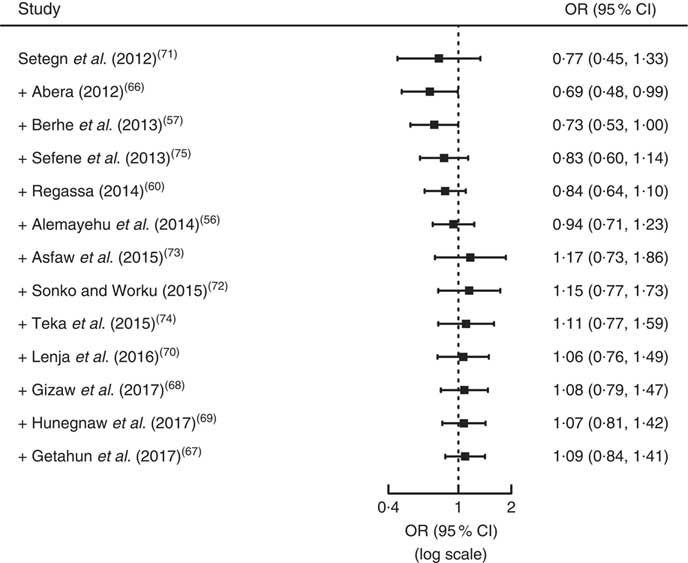

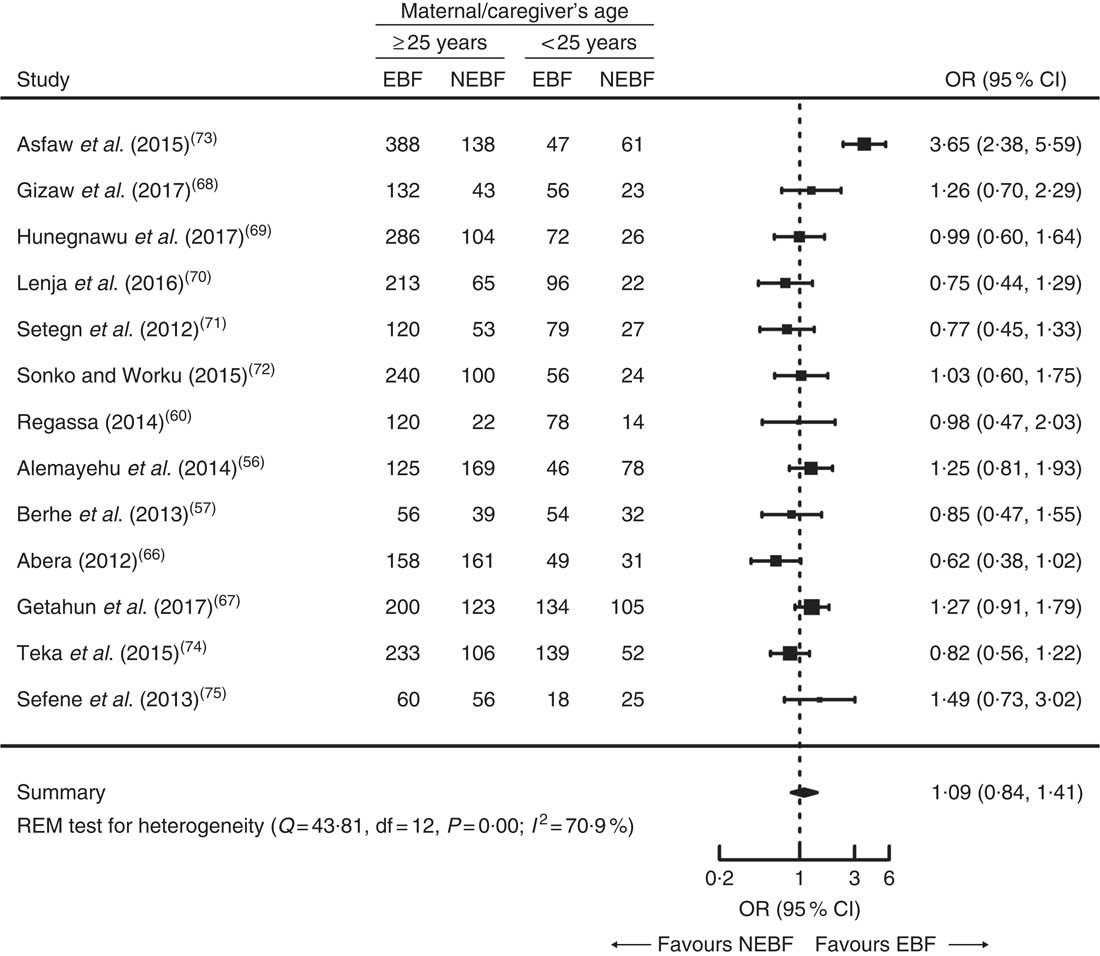

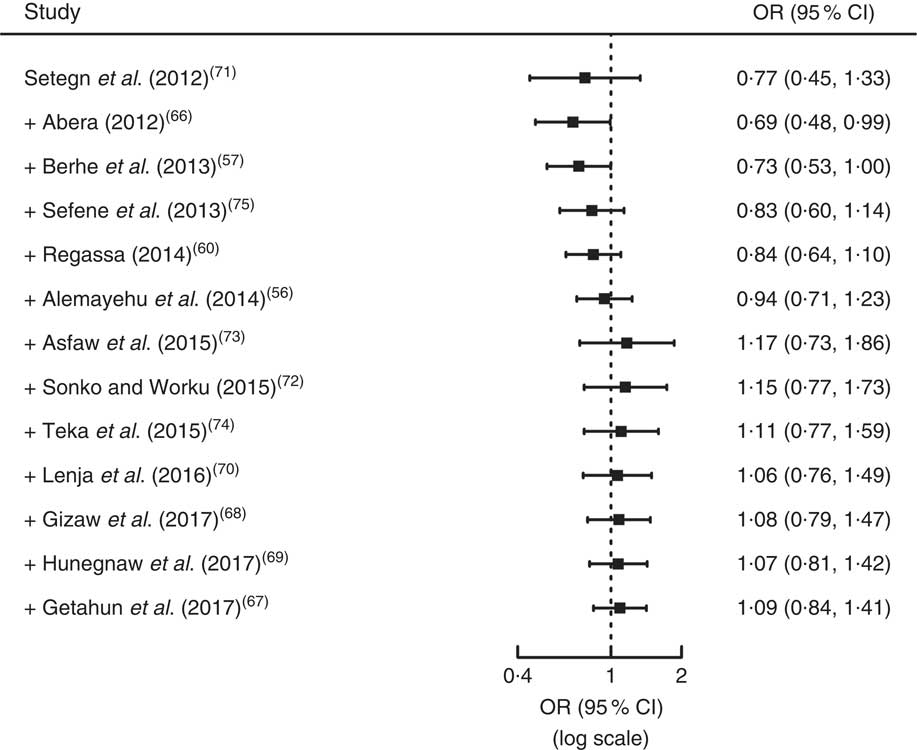

Thirteen studies( Reference Alemayehu, Abreha and Yebyo 56 , Reference Berhe, Mekonnen and Bayray 57 , Reference Regassa 60 , Reference Abera 66 – Reference Sefene, Birhanu and Awoke 75 ) involving 4929 individuals reported the association between EBF and maternal/caregiver’s age. As shown in Fig. 4, the pooled OR of maternal/caregiver’s age was 1·09 (95 % CI 0·84, 1·41, P=0·51). Mothers aged ≥25 years had 9 % higher chance of EBF during the first 6 months compared with mothers <25 years old; however, it was not statistically significant. Egger’s regression test for funnel plot asymmetry was not significant (z=−0·60, P=0·55; see online supplementary material, Supplemental Fig. 3).

Fig. 4 Forest plot of thirteen studies on the association of maternal/caregiver’s age with exclusive breast-feeding (EBF) in Ethiopia. The study-specific OR and 95 % CI are represented by the black square and horizontal line, respectively, with area of the square proportional to the specific-study weight to the overall meta-analysis. The centre of the black diamond represents the pooled OR and its width represents the pooled 95 % CI (NEBF, non-exclusive breast-feeding; REM, random-effects model)

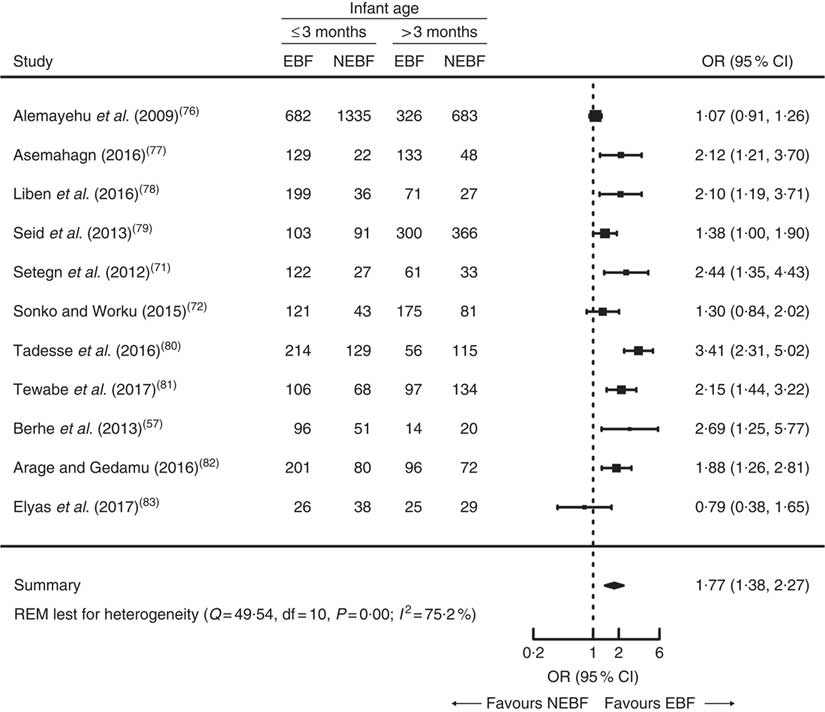

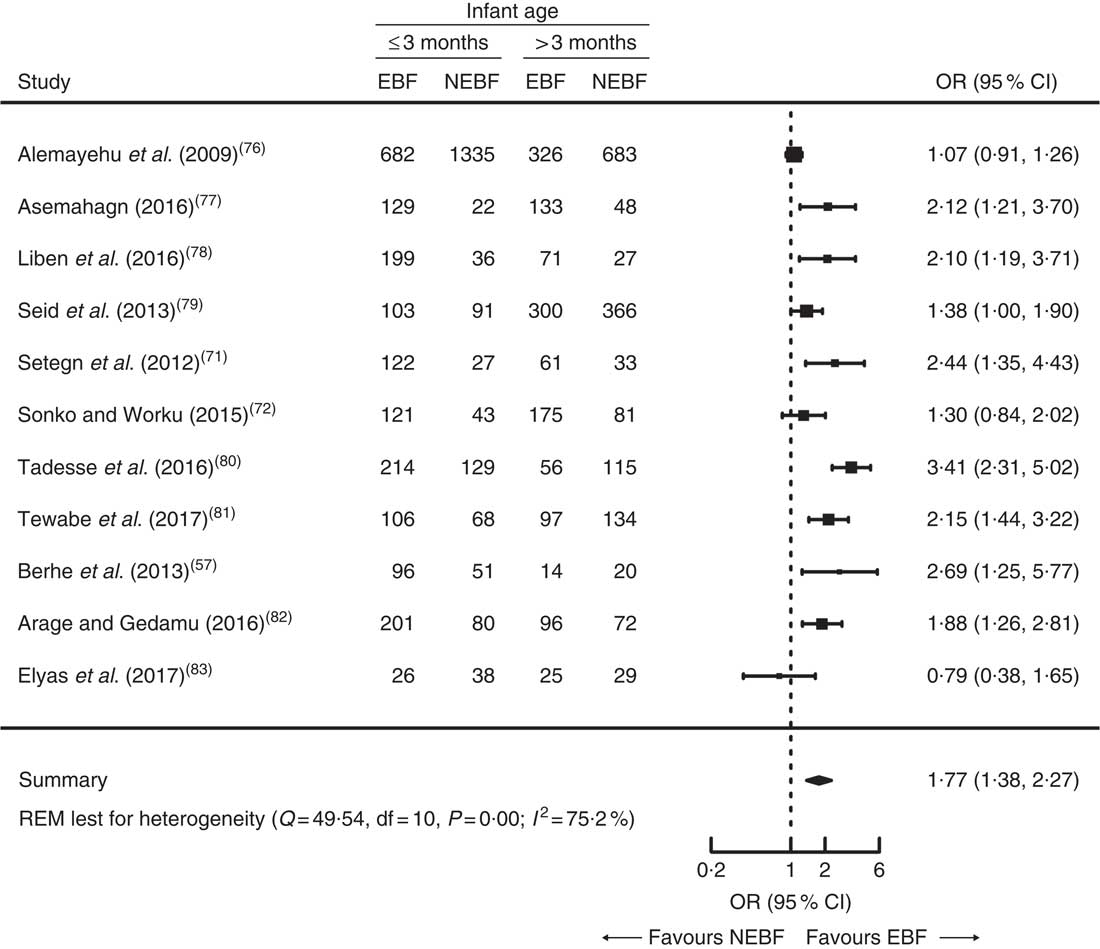

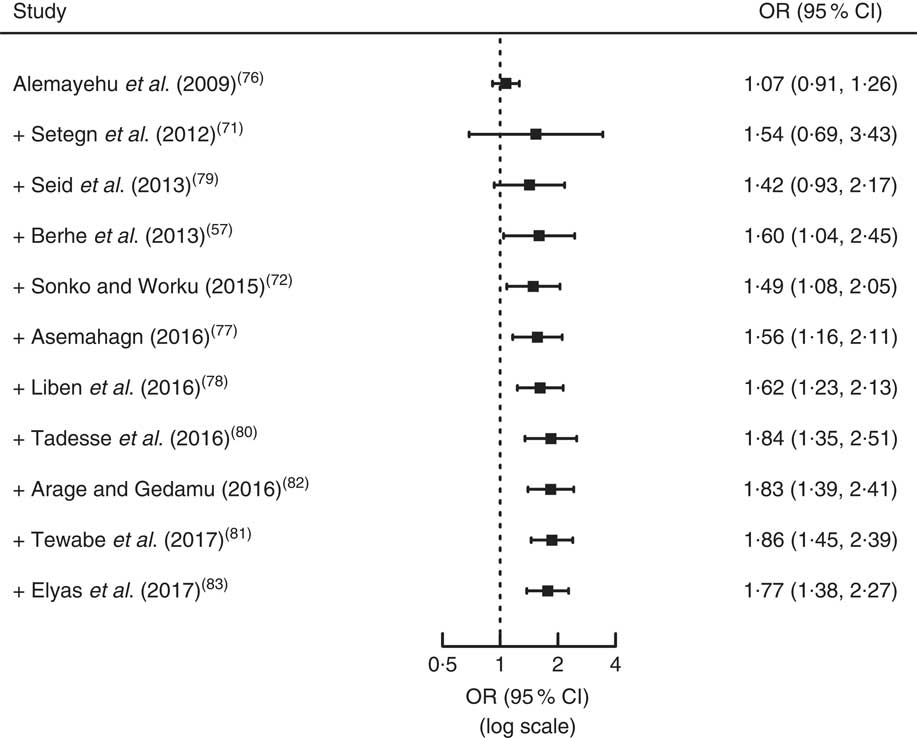

In addition, eleven( Reference Berhe, Mekonnen and Bayray 57 , Reference Setegn, Belachew and Gerbaba 71 , Reference Sonko and Worku 72 , Reference Alemayehu, Haidar and Habte 76 – Reference Elyas, Mekasha and Admasie 83 ) out of twenty-six studies reported the association between EBF and infant age with a total sample of 6881 mothers. The pooled OR of infant age was 1·77 (95 % CI 1·38, 2·27, P=0·001; Fig. 5). Children aged ≤3 months had 77 % statistically significant higher chance of being exclusively breast-fed compared with children >3 months old. Egger’s regression test for funnel plot asymmetry was not significant (z=0·82, P=0·41; see online supplementary material, Supplemental Fig. 4).

Fig. 5 Forest plot of eleven studies on the association of infant age with exclusive breast-feeding (EBF) in Ethiopia. The study-specific OR and 95 % CI are represented by the black square and horizontal line, respectively, with area of the square proportional to the specific-study weight to the overall meta-analysis. The centre of the black diamond represents the pooled OR and its width represents the pooled 95 % CI (NEBF, non-exclusive breast-feeding; REM, random effects model)

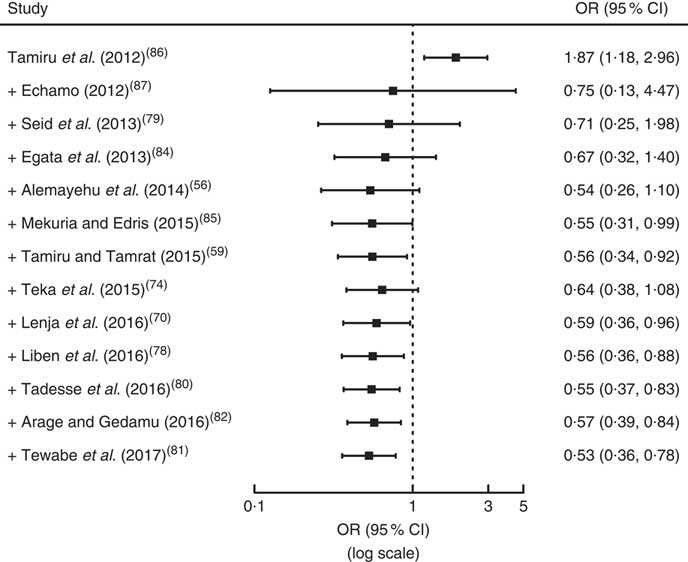

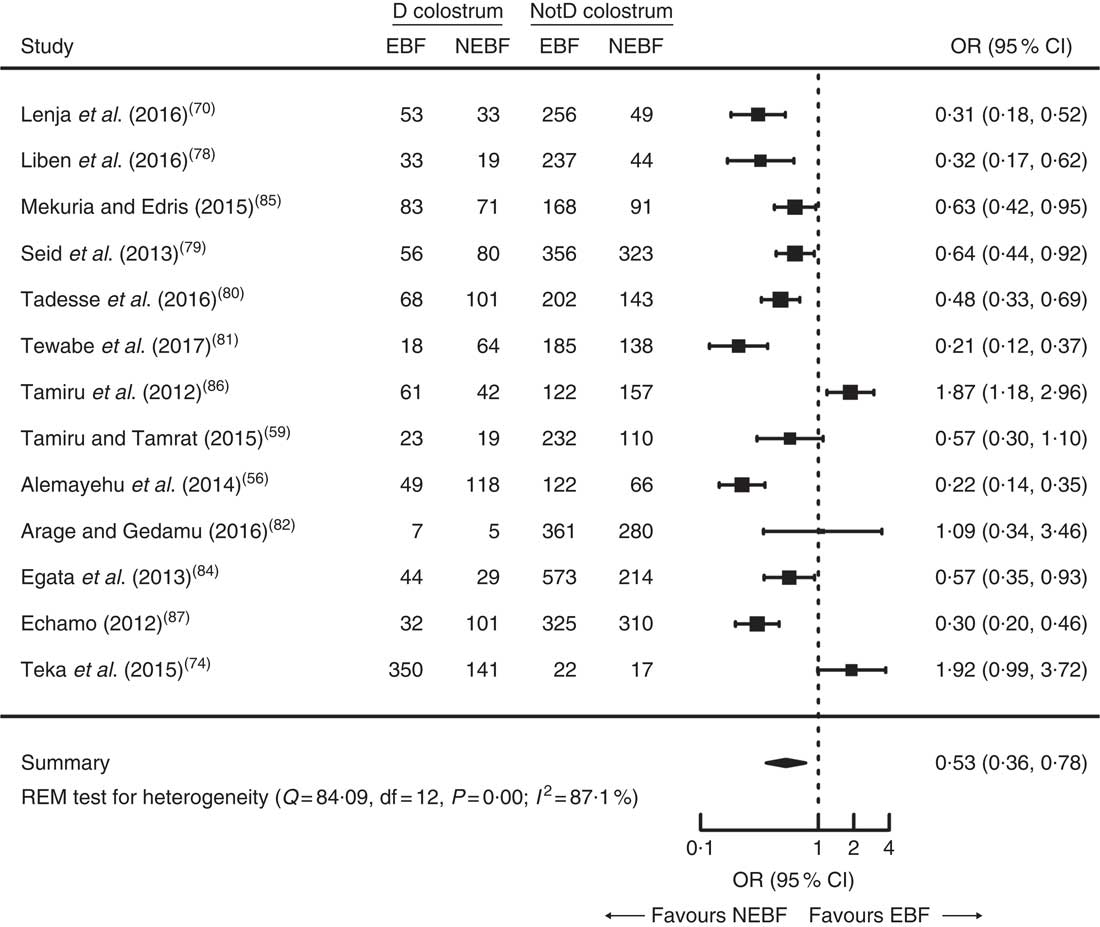

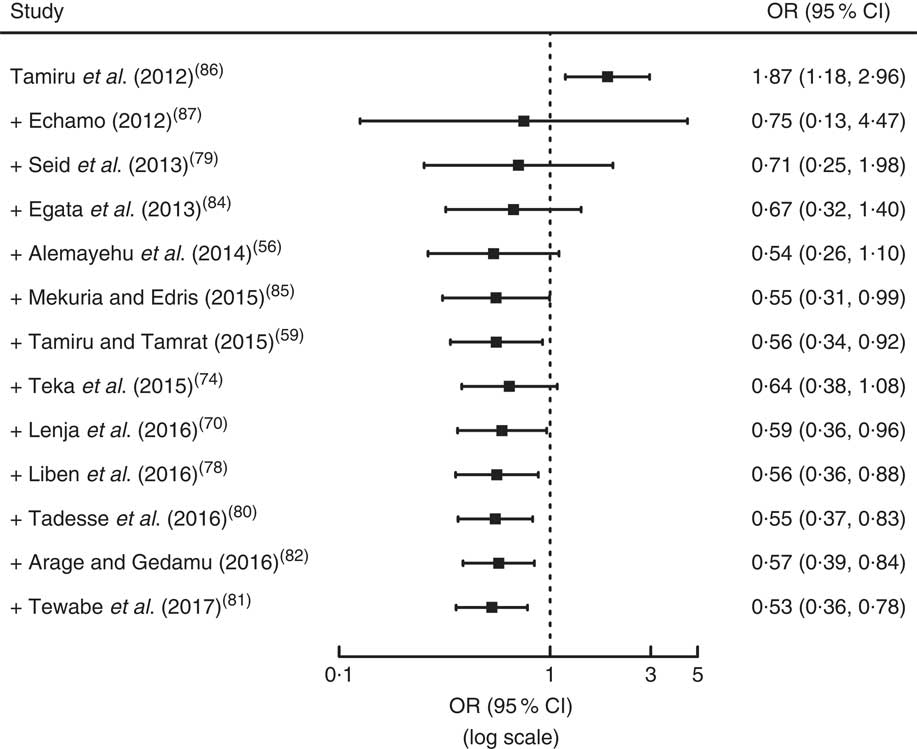

Finally, thirteen studies( Reference Alemayehu, Abreha and Yebyo 56 , Reference Tamiru and Tamrat 59 , Reference Lenja, Demissie and Yohannes 70 , Reference Teka, Assefa and Haileslassie 74 , Reference Liben, Gemechu and Adugnew 78 – Reference Arage and Gedamu 82 , Reference Egata, Berhane and Worku 84 – Reference Echamo 87 ) reported the association between EBF and colostrum discarding with a sample of 6803 mothers. As indicated in Fig. 6, the pooled OR of colostrum discarding was 0·53 (95 % CI 0·36, 0·78, P<0·001). Mothers who discard colostrum had 47 % statistically significant lower chance of EBF during the first 6 months compared with mothers who feed colostrum. Egger’s regression test for funnel plot asymmetry was not significant (z=0·84, P=0·40; see online supplementary material, Supplemental Fig. 5).

Fig. 6 Forest plot of thirteen studies on the association of discarding colostrum with exclusive breast-feeding (EBF) in Ethiopia. The study-specific OR and 95 % CI are represented by the black square and horizontal line, respectively, with area of the square proportional to the specific-study weight to the overall meta-analysis. The centre of the black diamond represents the pooled OR and its width represents the pooled 95 % CI (D, discarding; NotD, not discarding; NEBF, non-exclusive breast-feeding; REM, random-effects model)

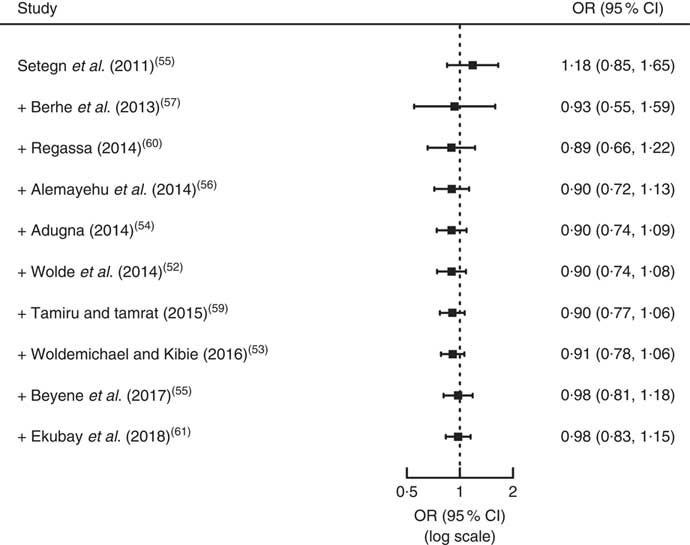

Cumulative meta-analysis

As illustrated in Fig. 7, the effect of increased maternal age on TIBF has been increasing slowly over time whereas the effect of discarding colostrum (Fig. 8) has been increasing dramatically. Similarly, the effect of maternal age (Fig. 9), discarding colostrum (Fig. 10) and infant age (Fig. 11) on EBF has been increasing.

Fig. 7 Forest plot showing the results from a cumulative meta-analysis of studies examining the effect of maternal age on timely initiation of breast-feeding in Ethiopia. The study-specific (first data point)/cumulative OR and 95 % CI are represented by the black square and horizontal line, respectively

Fig. 8 Forest plot showing the results from a cumulative meta-analysis of studies examining the effect of discarding colostrum on timely initiation of breast-feeding in Ethiopia. The study-specific (first data point)/cumulative OR and 95 % CI are represented by the black square and horizontal line, respectively

Fig. 9 Forest plot showing the results from a cumulative meta-analysis of studies examining the effect of maternal age on exclusive breast-feeding in Ethiopia. The study-specific (first data point)/cumulative OR and 95 % CI are represented by the black square and horizontal line, respectively

Fig. 10 Forest plot showing the results from a cumulative meta-analysis of studies examining the effect of discarding colostrum on exclusive breast-feeding in Ethiopia. The study-specific (first data point)/cumulative OR and 95 % CI are represented by the black square and horizontal line, respectively

Fig. 11 Forest plot showing the results from a cumulative meta-analysis of studies examining the effect of infant age on exclusive breast-feeding in Ethiopia. The study-specific (first data point)/cumulative OR and 95 % CI are represented by the black square and horizontal line, respectively

Meta-regression analysis

In studies reporting the association between TIBF and discarding colostrum, 95 % of the heterogeneity was due to variation in study area (region), residence of mothers, sample size and publication year. Based on the omnibus test, however, none of these factors influenced their association (QM=6·46, df=7, P=0·49; Table 3). In studies reporting the association between TIBF and maternal age, there was no statistically significant heterogeneity between studies (τ 2=2 %, Q=12·30, df=9, P=0·20); as a result, it is not relevant to investigate the possible reasons for heterogeneity.

Table 3 Meta-regression analysis to identify possible reasons for between-study heterogeneity in studies included in the present systematic review and meta-analysis on factors affecting timely initiation of breast-feeding (TIBF) and exclusive breast-feeding (EBF) in Ethiopia

SNNPR, Southern Nations, Nationalities and Peoples’ Region.

* Since we do not have a specific hypothesis, the reference category is selected arbitrarily.

† Residence is dropped from the model due to small sample size of included studies.

In EBF, 100·0, 88·2 and 51·1 % of the heterogeneity among studies reporting maternal age, infant age and discarding colostrum was due to variation in study area (region), residence of mothers, sample size and publication year, respectively. Based on the omnibus test, study area (region), publication year and sample size significantly influenced the association between maternal age and EBF practice (QM=42·27, df=9, P<0·001). Study area (region) and publication year also significantly influenced the association between infant age and EBF practice (QM=27·24, df=8, P=0·0006). Furthermore, residence and publication year significantly influenced the association between discarding colostrum and EBF (QM=16·66, df=8, P=0·03; Table 3).

Discussion

The present study examined the associations of TIBF and EBF with colostrum discarding, maternal/caregiver’s age and infant age. To our knowledge, our study is the first systematic review and meta-analysis on this topic in Ethiopia to date. The meta-analysis uncovered that colostrum discarding was significantly associated with TIBF but not maternal/caregiver’s age. On the other hand, colostrum discarding and infant age were found to be significantly associated with EBF but not maternal/caregiver’s age.

We found that mothers who discard colostrum had 62 % significantly lower chance of initiating breast-feeding within 1 h compared with mothers who feed colostrum to their child. This may be explained by the attempt of discarding colostrum to get white milk taking time, which therefore results in a delayed initiation of breast-feeding.

In the present meta-analysis, we found a statistically significant association between EBF and infant age. This finding confirmed our hypothesis and is consistent with a large body of evidence showing that increased infant age is negatively associated with EBF( Reference Senarath, Dibley and Agho 14 , Reference Victor, Baines and Agho 16 , Reference Nyanga, Musita and Otieno 26 , Reference Patel, Badhoniya and Khadse 27 , Reference Dorgham, Hafez and Kamhawy 88 , Reference Agho, Dibley and Odiase 89 ). This may be due to the fact that giving traditional postpartum care and support is common in Ethiopia immediately after birth, which may create opportunity for the mother to exclusively breast-feed the child. Since this traditional postpartum care and support decreases as the age of the infant increases, it may lead the mother to work outside. This may therefore force the mother to stop EBF. Evidence worldwide also agrees on the point that presence of social support is associated with better breast-feeding outcome( Reference Kanhadilok and McGrath 90 – Reference Kavle, LaCroix and Dau 93 ). Another possible reason is the workload and short maternity leave in Ethiopia, only two months postpartum until recently, which may influence the mother to withdraw EBF early. This hypothesis is supported by our previous meta-analyses( Reference Habtewold, Mohammed and Endalamaw 21 ), whereby maternal employment significantly lowered EBF, and other studies( Reference Balogun, Dagvadorj and Anigo 92 – Reference Ogbo, Eastwood and Page 95 ). Moreover, this could also be related to the short birth interval in Ethiopia.

We noted that colostrum discarding was significantly associated with EBF. The finding was in line with studies conducted in Nepal( Reference Chandrashekhar, Joshi and Binu 96 ) and Laos( Reference Barennes, Empis and Quang 97 ). This may be due to the fact that discarding colostrum leads to pre-lacteal feeding. In agreement with recent studies( Reference Radwan 98 – Reference Pandey, Tiwari and Senarath 103 ), maternal/caregiver’s age was not significantly associated with either EBF or TIBF. This is against our hypothesis and disproves the notion that older mothers have better breast-feeding experience than young mothers that helps them to practise optimal TIBF and EBF. However, there is robust evidence that, if supported, all reproductive-age mothers can maintain optimal TIBF and EBF equally( Reference Patel, Badhoniya and Khadse 27 , Reference Pereira-Santos, Santana and Oliveira 94 , Reference Perera, Ranathunga and Fernando 104 ). Therefore, the discrepancy may be due to the following reasons: (i) most studies used maternal age rather than age at first birth; (ii) different studies have used different age categories; and (iii) breast-feeding is not age dependent or can be confounded by innate maternal behaviour.

The present meta-analyses study has several implications. It provided evidence on breast-feeding practice and its associated factors in an Ethiopian context, which can be useful for cross-country/cross-cultural comparison and for breast-feeding improvement initiatives in Ethiopia. The present study provides an overview of up-to-date evidence for nutritionists and public health professionals. The findings also indicate emphasis should be given for all age groups of mothers/caregivers during breast-feeding intervention. Furthermore, the study points out that colostrum discarding and associated beliefs should be considered during designing breast-feeding interventions.

The association was estimated in a large sample size and recent and nationally representative studies were included. In addition, the present systematic review and meta-analysis was conducted based on a registered and published protocol, and guidelines for the Meta-analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) were strictly followed. The study has also several limitations. First, some studies were excluded because of the difference in age category. Second, almost all included studies were observational, which hinders inference of causality. Third, even though we used broad search strategies, the possibility of missing relevant studies cannot be fully exempted. Fourth, based on the conventional methods of statistical testing, a few analyses suffered from high levels of between-study heterogeneity. The cause of the heterogeneity was carefully explored and may be due to differences in study area; therefore, the result should be interpreted with caution.

Conclusion

In conclusion, colostrum discarding was a possible barrier for both TIBF and EBF. Additionally, increased infant age was found to be a risk factor for non-EBF. However, maternal/caregiver’s age was not a determinant factor for both TIBF and EBF. Interventions targeted on increasing the rate of TIBF and EBF should give special focus on colostrum discarding. In addition, future research is required to identify other factors affecting duration of EBF in Ethiopia. Further investigation is also required to assess the effect of age at first birth.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: The authors’ special gratitude goes to Sjoukje van der Werf (University of Groningen, the Netherlands) for her support developing the search strings and Balewgizie Sileshi (University of Groningen, the Netherlands) for his support during title and abstract screening. Financial support: This study received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors. Conflict of interest: None declared. Authorship: T.D.H. and S.M.A. conceived of and designed the study. T.D.H. developed syntax for searching databases and analysed the data. T.D.H. and S.M.A. wrote and revised the manuscript. All authors read the submitted manuscript and gave final approval. Ethics of human subject participation: Not applicable.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980019000314