Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM), which refers to carbohydrate intolerance with the onset or first recognition during pregnancy(Reference Rani and Begum1,Reference Ben-Haroush, Yogev and Hod2) , may increase the risk of maternal and perinatal complications. In pregnant women, it is associated with hypertension, preeclampsia, increased operative intervention and future diabetes(Reference Rani and Begum1,Reference Damm, Houshmand-Oeregaard and Kelstrup3,Reference Nilsson4) . The perinatal complications include macrosomia, diabetes, metabolic syndrome and subsequent childhood and adolescent obesity(Reference Rani and Begum1,Reference Damm, Houshmand-Oeregaard and Kelstrup3,Reference Nilsson4) .

The prevalence of GDM ranges from 2 to 20 % worldwide, and it was reported to be up to 19·7 % in Beijing(Reference Zhu, Yang and Wang5). The wide prevalence of GDM had caused an economic burden of about $5·59 billion in 2015 at Chinese national level(Reference Xu, Dainelli and Yu6), which has already become an important public health problem. Determining the risk factors of GDM could help us to diagnose GDM at an early stage, so that we can take preventive measures against GDM to mitigate the GDM burden for individuals, local communities and healthcare systems.

The aetiology of GDM is complicated as it was involved in multiple factors including genetic and environmental factors. Genome-wide association studies and candidate gene profiling have revealed the association between GDM and variants on several genes that are related to insulin secretion, insulin resistance, lipid and glucose metabolism and other pathways(Reference Teler, Tarnowski and Safranow7–Reference Kwak, Kim and Cho10). Glucokinase gene (GCK), one of the candidates for GDM, locates on 7p13 and encodes a glucokinase which is the main glucose-phosphorylating enzyme expressed only in the pancreatic beta cell and liver(Reference Shaat, Karlsson and Lernmark11,Reference Chiu, Go and Aoki12) . Mutations on GCK that altered enzyme activity are associated with HbA1c levels, fasting glucose concentrations and GDM(Reference Tam, Ho and Wang13). The GCK rs4607517 polymorphism may alter a signalling characteristic of insulin secretion such as pulsatility. This change led to insulin resistance and impaired fasting glucose(Reference Muller, Piaggi and Hoffman14,Reference Hong, Chung and Cho15) . However, recent investigations showed that the association between rs4607517 and GDM is inconsistent across studies, especially among Chinese population(Reference Mao, Li and Gao16,Reference Wang, Nie and Li17) . Some confounding factors such as lifestyles may have impacts on the effect of this polymorphism on GDM.

Dietary behaviours, such as high intake of sugar-sweetened beverages, fried foods and animal fat before or/and during pregnancy, had been linked to GDM(Reference Zhang, Rawal and Chong18–Reference Belzer, Smulian and Lu20). A high amount of sugar had been directly linked to impaired pancreatic beta cell function in humans(Reference Davis, Ventura and Weigensberg21). Eventually, the pancreatic beta cell response may fail to produce sufficient insulin to maintain normoglycaemia(Reference Maki, Nieman and Schild22). The interactions between gene and environmental exposures (such as dietary and physical activity behaviours) may be important in the aetiology of GDM(Reference Kurbasic, Poveda and Chen23). Both the GCK rs4607517 polymorphism and sweets consumption are associated with pancreatic beta cell function. Yet whether the effect of GCK polymorphism on GDM is conditional on the consumption of sweet foods (gene–environment interaction) is still unknown.

Here, we conducted a case–control study among 1015 Chinese pregnant women (562 GDM cases and 453 controls) to identify the association between the GCK rs4607517 polymorphism and GDM and to evaluate the interaction between sweets consumption and GCK rs4607517 polymorphism on GDM.

Methods

Study design and participants

This case–control study was conducted among 1015 Chinese women, which was described previously(Reference Ao, Wang and Wang24). In brief, the pregnant women aged 20–49 years and at 24–28 gestation weeks were recruited consecutively from the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology of Peking University First Affiliated Hospital in Beijing from May 2012 to November 2013. The exclusion criteria for subjects were as follows: women who had pre-existing diabetes, or abnormal result in a glucose screening test before the 24th week of gestation, or multiple gestations or maternal diseases such as hypertension, endocrine disorders and hepatic diseases; women with incomplete medical information and who had decided to give birth at another hospital; women who were unable or unwilling to get involved in the study(Reference Ao, Wang and Wang24,Reference Wang, Wang and Ao25) . Ultimately, 562 cases and 453 controls were enrolled in this study.

All pregnant women were screened for GDM at 24–28 gestation weeks with a 75-g, 2-h oral glucose tolerance test after overnight fast, according to the criteria established by the Ministry of Health of China in 2011(Reference Yang26). The GDM was diagnosed if one or more plasma glucose levels met or exceeded the thresholds as follows: fasting plasma glucose 5·1 mmol/l, 1-h plasma glucose 10·0 mmol/l or 2-h plasma glucose 8·5 mmol/l. The controls were pregnant women having normal glucose tolerant, which was identified by the oral glucose tolerance test at 24–28 gestation weeks.

Questionnaires

The clinical and biochemical data were collected from the hospital computer database by the trained medical record abstractors, which included self-reported pre-pregnancy weight and height measured at the first prenatal visit. The pre-pregnancy BMI was calculated as pre-pregnancy weight in kilogram divided by height in meter squared.

Pregnant women were recruited into the study as soon as their GDM status was determined. Lifestyle behaviours investigation was performed before the women with GDM participated in exercise and diet intervention. Women completed a lifestyle behaviours questionnaire which was modified for the purposes of our study based on the standardised self-report questionnaire used in the China Chronic Disease and Risk Factor Surveillance(Reference Meng, Huang and Cheng27,Reference Li, Zhang and Jiang28) . The frequencies of lifestyle behaviours during the last 3 weeks before pregnancy were reported. Consumption of sweets (such as ice cream, cakes, pies, chocolate and biscuits) was divided into two categories by average consumption: <once/week and ≥once/week. Consumption of other foods was divided into two categories by the median of average consumption: vegetables and fruits (<3950 g/week and ≥3950 g/week); meat such as beef, pork, chicken and lamb (<700 g/week and ≥700 g/week); staple foods such as noodles, steamed bun and rice (<1400 g/week and ≥1400 g/week); fried foods such as fried potatoes, fried chicken, fried fish, donuts and snack chips (<once/week and ≥once/week). Sedentary behaviour time (total sitting time/d) was also divided into two categories based on the median (50th percentile): <3·5 h/week and ≥ 3·5 h/d.

Genotyping

Genomic DNA was extracted from peripheral blood samples by salting-out procedure. A detailed account on the genotyping procedures has been reported previously(Reference Ao, Wang and Wang24). Briefly, genotyping of the rs4607517 polymorphism was carried out with Sequenom’s MassARRAY platform (Agena) according to the manufacturer’s instructions(Reference Gabriel, Ziaugra and Tabbaa29). The genotyping success rate for the rs4607517 polymorphism on the platform exceeded 98 %. Negative controls and two samples were placed in duplicate on each run, to ensure correct genotyping.

Statistical analyses

The distribution of quantitative or categorical variables in both GDM and control groups is expressed as mean ± sd or number (frequency), and the differences between two groups were tested by t test or χ 2 test, respectively. The χ 2 test was also used to determine whether the Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium of rs4607517 existed among the controls. Logistic regression was performed under the additive genetic model to evaluate the association between the rs4607517 polymorphism and the risk of GDM. Then, the stratified analyses by sweets consumption (<1/week; ≥1/week) were conducted to test the interaction between rs4607517 and sweets consumption. OR are presented with 95 % CI. A two-sided P value <0·05 was considered to be statistically significant. The statistical analyses were performed with SPSS version 18.0 (SPSS Inc.).

Results

General characteristics of the study population

The general characteristics of the GDM patients and controls are shown in Table 1. The women with GDM were older and had greater pre-pregnancy BMI than the controls.

Table 1 General characteristics of participants*

GDM, gestational diabetes mellitus.

* P values were calculated by t tests or χ 2 tests.

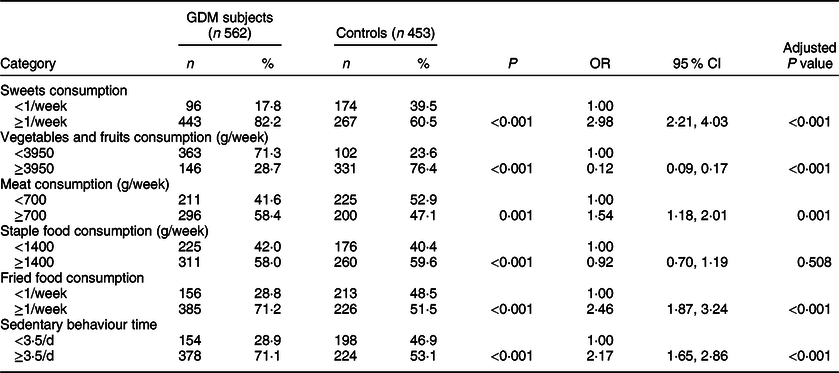

By logistic regression analysis, comparing with less sweets consumption (<1/week), higher sweets consumption before pregnancy (≥1/week) was associated with the increased risk of GDM (OR 2·98, 95 % CI 2·21, 4·03; P < 0·001), after adjusting for age and pre-pregnancy BMI. The similar association was also found between GDM and vegetables and fruits consumption, meat consumption, fried food consumption or sedentary behaviour time (Table 2).

Table 2 Food consumption and sedentary behaviour time of participants

GDM, gestational diabetes mellitus.

* P values were calculated by χ 2 tests. OR and adjusted P values for food consumption and sedentary behaviour time were calculated by logistic regression adjusted for age and pre-pregnancy BMI.

Association of rs4607517 with gestational diabetes mellitus

No deviation from Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium was observed for rs4607517 in the control group (P = 0·796). The genotype frequencies in the GDM subjects and controls are presented in Table 3. The rs4607517 A allele was significantly associated with GDM after adjusting for age, pre-pregnancy BMI, fruits and vegetables consumption, meat consumption, staple food consumption, fried food consumption and sedentary behaviour time under additive genetic model (OR 1·35, 95 % CI 1·03, 1·77; P = 0·028).

Table 3 Genotype frequencies of rs4607517 and its OR for gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM)

* Adjusted for age, pre-pregnancy BMI, fruits and vegetables consumption, meat consumption, staple food consumption, fried food consumption and sedentary behaviour time under additive genetic model.

Interaction between rs4607517 and sweets consumption on gestational diabetes mellitus

In the subgroups with different sweets consumption, we only found that the A allele of rs4607517 was associated with GDM in women with sweets consumption ≥1/week (OR 1·61, 95 % CI 1·17, 2·21; P = 0·003; Table 4). Furthermore, we tested the interaction term between rs4607517 and sweets consumption in the logistic regression model including age, pre-pregnancy BMI, fruits and vegetables consumption, meat consumption, staple food consumption, fried food consumption, sedentary behaviour time, rs4607517, sweet consumption and rs4607517 × sweet consumption as independent variables. Sweet consumption and the A allele of the GCK rs4607517 polymorphism had significant interaction with GDM (OR 2·84, 95 % CI 1·39, 5·81; P = 0·004). None of the interactions between other food consumption or sedentary behaviour time and the GCK rs4607517 polymorphism on GDM was statistically significant (P for interaction > 0·05 for all interaction tests, Table 5).

Table 4 Interaction between the glucokinase gene (GCK) rs4607517 polymorphism and sweets consumption on gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM)

Bold values were considered to be statistically significant. (1) In the subgroups with different sweets consumption, we only found the A-allele of rs4607517 was associated with GDM in women with sweets consumption ≥1 per week (P = 0·003). (2) Sweet consumption and the A-allele of the GCK rs4607517 polymorphism had significant interaction with GDM (P = 0·003). (3) In the subgroups with different meat consumption, we only found the A-allele of rs4607517 was associated with GDM in women with meat consumption <700 g/week (P = 0·011). However, none of the interactions between other food consumption or sedentary behavior time and the GCK rs4607517 polymorphism on GDM were statistically significant.

* OR with 95 % CI and P value of rs4607517 were estimated with logistic regression analysis in each behavioural level under additive genetic model adjusted for age, pre-pregnancy BMI, fruits and vegetables consumption, meat consumption, staple food consumption, fried food consumption and sedentary behaviour time.

† OR with 95 % CI and P value of rs4607517 × sweets consumption were estimated with logistic regression analysis under additive genetic model adjusted for age, pre-pregnancy BMI, fruits and vegetables consumption, meat consumption, staple food consumption, fried food consumption and sedentary behaviour time.

Table 5 Interaction between the glucokinase gene rs4607517 polymorphism and food consumption on gestational diabetes mellitus

Bold values were considered to be statistically significant. (1) In the subgroups with different sweets consumption, we only found the A-allele of rs4607517 was associated with GDM in women with sweets consumption ≥1 per week (P = 0·003). (2) Sweet consumption and the A-allele of the GCK rs4607517 polymorphism had significant interaction with GDM (P = 0·003). (3) In the subgroups with different meat consumption, we only found the A-allele of rs4607517 was associated with GDM in women with meat consumption <700 g/week(P = 0·011). However, none of the interactions between other food consumption or sedentary behavior time and the GCK rs4607517 polymorphism on GDM were statistically significant.

* OR with 95 % CI and P value of rs4607517 were estimated with logistic regression analysis in each behavioural level under additive genetic model adjusted for age and pre-pregnancy BMI.

† OR with 95 % CI and P value of rs4607517 were estimated with logistic regression analysis in each behavioural level under additive genetic model adjusted for age, pre-pregnancy BMI, other food consumption and sedentary behaviour time.

‡ OR with 95 % CI and P value of rs4607517 × food consumption were estimated with logistic regression analysis under additive genetic model adjusted for age, pre-pregnancy BMI, other food consumption and sedentary behaviour time.

Discussion

In the current study, we found that the GCK rs4607517 polymorphism was associated with the risk of GDM. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study reporting the interaction between the GCK rs4607517 polymorphism and sweets consumption on GDM.

The GCK gene encodes a member of the hexokinase family proteins. Hexokinase phosphorylate glucose produces glucose-6-phosphate, the first step in most glucose metabolism pathways. The use of multiple promoters and alternative splicing of this gene result in distinct protein isoforms that exhibit tissue-specific expression in the pancreas and liver(Reference Mahmoodi, Zarei and Rezaeian30). In pancreas, this enzyme plays a role in glucose-stimulated insulin secretion(Reference Ohn, Kwak and Cho31), while in liver, this enzyme is important in glucose uptake and conversion to glycogen. Previous studies have shown that mutations on GCK that altered enzyme activity reduced glucose-stimulated insulin secretion and increased the risk of GDM(Reference Shaat, Karlsson and Lernmark11,Reference Hong, Chung and Cho15,Reference Mao, Li and Gao16,Reference Han, Cui and Chen32) . Accordingly, in the current study, the GCK rs4607517 polymorphism was associated with the increased risk of GDM. However, a previous study showed that the GCK rs4607517 polymorphism has not significant association with GDM in pregnant Chinese women after adjusting for age and pre-pregnancy BMI(Reference Wang, Nie and Li17). This was probably due to some confounding factors such as lifestyle factors, other than ethnicity, modify the effect of this polymorphism(Reference Song, Song and Wang33).

The current study found that the sweets consumption before pregnancy was associated with GDM. Previous studies showed that high amount of sugar had association with impaired pancreatic beta cell function in humans(Reference Davis, Ventura and Weigensberg21,Reference Maki, Nieman and Schild22,Reference Lana, Rodríguezartalejo and Lopezgarcia34) , such that greater consumption of sugar-sweetened product (710 ml non-diet soda and 108 g non-dairy pudding) resulted in the decline of liquid meal tolerance test disposition index, suggesting that the pancreatic beta cell has response (relative to insulin sensitivity) to deteriorated(Reference Maki, Nieman and Schild22). The detailed molecular mechanism remains unclear and speculative, but may involve in oxidative stress and inflammation which can cause pancreatic beta cell dysfunction(Reference Noel, Fernandes and Rodrigo35–Reference Joseph37). Further investigations should be conducted to clarify the relationships among sweet consumption, oxidative stress, inflammation and GDM. Moreover, that sweets consumption before pregnancy contributed to the pancreatic beta cell dysfunction may have a deleterious effect during pregnancy, suggesting that it is a risk factor for GDM(Reference Zhang, Schulze and Solomon38). Normal pregnancy is characterised by profound metabolic stresses on glucose homoeostasis including insulin resistance, especially in the late pregnancy (mainly third trimester). In women with sweets consumption (≥once/week) before pregnancy, beta cell dysfunction may worsen further during pregnancy when the insulin resistance of pregnancy is partially additive and this could increase the risk of GDM(Reference Zhang, Schulze and Solomon38,Reference Mccurdy and Friedman39) .

Both the GCK rs4607517 polymorphism and high amount of sugar have been reported to be associated with decreased beta cell function(Reference Hong, Chung and Cho15,Reference Davis, Ventura and Weigensberg21) , suggesting that they may have interactions accounting for the risk of GDM. It should be noticed that we observed strong interaction between the GCK rs4607517 polymorphism and habitual intake of sweets before pregnancy on the risk of GDM. The rs4607517 A allele was significantly associated with higher risk of GDM only in women with sweets consumption ≥1/week. This suggested that women with the rs4607517 A allele had a higher risk of GDM if they also had a habitual consumption of sweet foods. There was no significant association between GCK rs4607517 and GDM in women with sweets consumption less than once per week. Common variations in GCK including rs4607517 are associated with a modest effect on carbohydrate oxidation, fasting glucose and fasting insulin, leading to diabetes(Reference Muller, Piaggi and Hoffman14,Reference McKeown, Dashti and Ma40) . These may make an individual with GCK rs4607517 A allele more susceptible to the harmful effects of a poor diet such as habitual sweets consumption(Reference Prasad and Groop41). According to another study, following up 4106 participants with normal glucose tolerance for 10 years, the GCK rs4607517 polymorphism was significantly associated with progression to prediabetes leading to beta cell dysfunction in response to progressive decline in insulin sensitivity. The environmental factors including increased energy intake may have important roles in the pronounced decrease in insulin sensitivity soon before development of diabetes among the progressors to diabetes(Reference Ohn, Kwak and Cho42). A large meta-analysis of six discovery and five replication cohorts observed a suggestive interaction between sugar-sweetened beverage intake with GCK rs4607517 polymorphism only in women for fasting insulin(Reference McKeown, Dashti and Ma40). However, the mechanism of GCK–environment interaction effect is not well understood and awaits future functional studies in liver or pancreatic biopsy tissues.

The study findings suggested that lifestyle interventions introduced before pregnancy have the potential in preventing GDM. Thus, it is important for women with the GCK rs4607517 A allele who plan to have a child to consider strict control of sweets consumption before pregnant for preventing GDM.

There were some limitations in the current study. First, assessment with simple FFQ was lack of information such as the portion size. Further investigation should be conducted with more information in dietary intake. Second, the reported interactions may be confounded by other lifestyle factors such as food intake during pregnancy, which was not available in the current study. Third, GDM patients and controls were selected at a third-tier hospital of Beijing which may not be representative of the general population in China(Reference Ao, Wang and Wang24). Fourth, case–control study is not as powerful as other types of study in confirming a causal relationship. However, the case–control study design is suitable for clarifying the association.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the case–control study demonstrated that the GCK rs4607517 polymorphism was associated with GDM in Chinese women. In particular, we for the first time reported the interaction between the GCK rs4607517 polymorphism and sweets consumption on GDM. These results provided novel evidence for risk assessment and personalised prevention of GDM. Future large-scaled population studies are needed to confirm the interaction between the GCK polymorphism and sweets consumption on the development of GDM.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: The authors thank all the participants for their contribution to the study. Financial support: The current research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors. Conflict of interest: The authors declare no duality of interest associated with this manuscript. Authorship: H.-J.W. and H.-X.Y. were responsible for the conception and design of the study. D.A. collected the data including genotypes. D.A. and Q.Z. conducted the statistical analyses. D.A. wrote the first draft of the paper, which was critically revised by H.-J.W. and H.-X.Y. All authors contributed to interpretation of the findings. The final manuscript was approved by all authors. Ethics of human subject participation: The current study was conducted according to the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki, and all procedures involving study participants were approved by the Peking University Biomedical Ethics Committee (IRB00001052-12043). Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects.