Over the past few decades, childhood overweight has emerged as an important public health problem worldwide(Reference Branca, Nikogosian and Lobstein1–Reference Ogden, Carroll, Curtin, McDowell, Tabak and Flegal3). In the USA the prevalence of obesity (BMI ≥ 95th percentile) in 6- to 11-year-old children has increased from 4·2 % in the 1960s to 18·8 % in 2004(Reference Ogden, Carroll, Curtin, McDowell, Tabak and Flegal3, Reference Ogden, Flegal, Carroll and Johnson4). Although in most European countries the prevalences are somewhat lower, there have also been dramatic increases over the past few decades(Reference Branca, Nikogosian and Lobstein1). Recently, however, several countries including France, Italy and Sweden have reported a stabilization or a decrease in the prevalence of childhood overweight(Reference Peneau, Salanave and Maillard-Teyssier5–Reference Salanave, Peneau, Rolland-Cachera, Hercberg and Castetbon9).

In 2002, the first nationally representative study determining the prevalence of childhood overweight and obesity in Switzerland reported that almost 20 % of primary-school children were overweight and of those over 6 % were obese(Reference Zimmermann, Gubeli, Puntener and Molinari10). Compared with regional data from the 1960s and the 1980s, these numbers represented more than a fivefold increase for the overall overweight prevalence(Reference Zimmermann, Gubeli, Puntener and Molinari10).

Since the publication of these data, awareness of the problem in Switzerland has increased and different programmes and initiatives have been launched in order to combat childhood overweight. Therefore the aim of the present follow-up study was to monitor the development of the childhood overweight prevalence and to determine whether the situation has changed over the examined period of 5 years. In addition, the prevalence of underweight was assessed for both time points in order to see whether a change in the prevalence of overweight also affects the rate of underweight.

Subjects and methods

Subjects

For both 2002 and 2007, a probability-proportional-to-size cluster sampling based on current census data was used to obtain a representative national sample of 2500 Swiss children aged 6–13 years. This sample size represents about one in 250 children in this age group in Switzerland (Swiss Federal Department of Statistics, personal communication). The country was divided into five regions: south (Italian language), north-east (German language), north-west (German language), central east (German language) and west (French language). Furthermore, all communities were grouped into strata by population size: <10 000, between 10 000 and 100 000, and >100 000 inhabitants. By stratified random selection, sixty schools were identified across Switzerland; the stratification scheme has been described in more detail previously(Reference Zimmermann, Gubeli, Puntener and Molinari10). After acceptance of participation of the schools, three or four classes (depending on class sizes) were randomly selected from each school and all students from those classrooms were invited to participate. The average number of participants per school was forty-five students in 2002 and thirty-eight students in 2007, but it varied according to class sizes and response rate. The data from the study conducted in 2002 have been published elsewhere(Reference Zimmermann, Gubeli, Puntener and Molinari10, Reference Zimmermann, Gubeli, Puntener and Molinari11).

Ethical approval for both studies was obtained from the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology, Zurich, Switzerland. Written informed consent was obtained from all parents or guardians of the participating children and oral assent was obtained from the children.

Methods

Before the measurements, which took place over the entire school day, the subjects removed their shoes or slippers as well as pullovers, emptied their pockets and wore only light indoor clothing. Height and weight were measured using standard anthropometric techniques(12). Body weight was measured to the nearest 0·1 kg using a digital scale (BF 18; Breuer, Ulm, Germany) calibrated with standard weights. Height was measured to the nearest 0·1 cm using a portable stadiometer (Seca 214; Seca Medizinische Waagen und Messsysteme, Hamburg, Germany). BMI was calculated as weight divided by the square of height (kg/m2). All measurements were done by the same two trained investigators at each time point; however, the investigators were not the same in 2002 and 2007.

All heads of the schools participating in the study were given a questionnaire to fill out asking about measures taken with regard to increasing physical activity and/or improving nutrition during the past 5 years.

Statistical analysis

To define underweight, overweight and obesity, the 5th, 85th and 95th BMI-for-age reference percentiles of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention were used(Reference Ogden, Kuczmarski, Flegal, Mei, Guo, Wei, Grummer-Strawn, Curtin, Roche and Johnson13); these have previously been validated in Swiss primary-school children(Reference Zimmermann, Gubeli, Puntener and Molinari11). Statistical analysis was performed using SPLUS® 8·0 Enterprise Developer (Insightful Corporation, Seattle, WA, USA), SPSS for Windows version 16 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) as well as Microsoft® Excel 2003 (Microsoft Corp., Redmond, WA, USA) software packages. The χ 2 test was used to check for significant differences between prevalences at the two time points and the z test to check for significant differences between means in 2002 and 2007. The level of significance was set at 0·05.

To analyse for geographic differences, the five clusters that had been used for the sampling (described in detail above) were applied. For demographic differences, the strata by population size (also explained above) were used.

Results

Basic characteristics of the subjects in both study groups are displayed in Table 1. In the 2002 study, fifty-seven schools accepted to participate in the study; in these schools, 3414 children and their parents were invited to take part in the measurements and 2672 accepted. At the day of measurement sixty-four were absent, which resulted in an overall participation rate of 76·4 %. After excluding subjects with incomplete data as well as a small number of children aged below 6 or above 13 years, a total of 2431 subjects remained, which consisted of 1196 boys (mean age 9·8 (se 0·05) years) and 1235 girls (mean age 9·8 (se 0·05) years).

Table 1 Basic characteristics of the national samples of Swiss children in 2002 and 2007

*Mean values were significantly different from those in 2002 (z test): P < 0·05.

In 2007, at the sixty schools which accepted to participate in the study, 3188 children and their parents were invited to take part in the examinations. Of these, 2395 accepted to participate, but eighty-five were absent at the day of measurement. The overall response rate was 72·5 %. After excluding eighty-eight subjects who were either below 6 years of age or above 13 years of age, 2222 children remained. The final sample consisted of 1083 boys (mean age 10·0 (se 0·05) years) and 1139 girls (mean age 10·0 (se 0·05) years).

Detailed results on the prevalences of overweight and obesity in 2002 have been published elsewhere(Reference Zimmermann, Gubeli, Puntener and Molinari10, Reference Zimmermann, Gubeli, Puntener and Molinari11). The prevalences of underweight (<5th percentile), overweight (≥85th and <95th percentile) and obesity (≥95th percentile) by age in 2007 are given in Table 2. The prevalences of underweight, overweight and obesity did not differ significantly between the different age groups. There was no significant gender difference for underweight and overweight children, but the prevalence of obese boys was significantly higher than the prevalence of obese girls (P < 0·05).

Table 2 The prevalence of underweight, overweight and obesity in a national sample of Swiss children in the year 2007 by age, using the CDC BMI reference criteria

CDC, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

CDC BMI reference criteriaReference Ogden, Kuczmarski, Flegal, Mei, Guo, Wei, Grummer-Strawn, Curtin, Roche and Johnson(13): underweight, BMI-for-age <5th percentile; overweight, BMI-for-age ≥85th and <95th percentile; obese, BMI-for-age ≥95th percentile.

None of the prevalences were significantly different between the age groups as assessed by the χ 2 test.

*Mean value was significantly different from that of boys: P < 0·05.

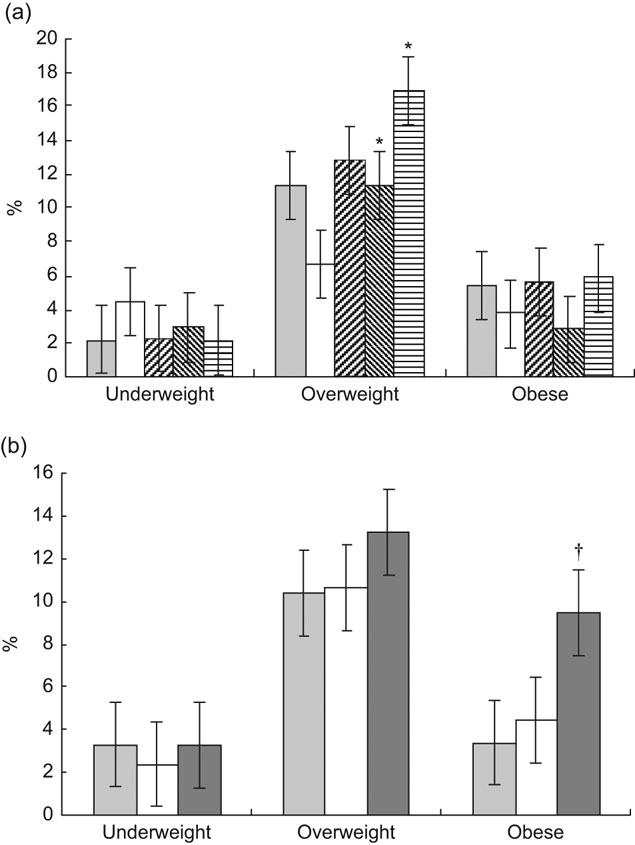

The geographic and demographic differences in underweight, overweight and obesity in 2007 are displayed in Fig. 1. In the study from 2002, no significant geographic or demographic differences had been observed(Reference Zimmermann, Gubeli, Puntener and Molinari10). In 2007, however, the prevalence of overweight was highest in the southern region, but the difference reached significance only compared with the central eastern region (P = 0·03). The prevalence of overweight was significantly higher in the north-western region compared with the central eastern region (P = 0·03). The geographic differences in the prevalences of underweight or obesity were not significant. The prevalences of both overweight and obesity were higher in communities with a population above 100 000 compared with the two smaller categories, but only the difference for obesity prevalence was statistically significant (P < 0·05).

Fig. 1 (a) Geographic (![]() , west;

, west; ![]() , central east;

, central east; ![]() , north-west;

, north-west; ![]() , north-east;

, north-east; ![]() , south) and (b) demographic (

, south) and (b) demographic (![]() , <10 000 inhabitants;

, <10 000 inhabitants; ![]() , 10 000–100 000 inhabitants;

, 10 000–100 000 inhabitants; ![]() , >100 000 inhabitants) differences in the prevalences of underweight, overweight and obesity in a national sample of 6- to 13-year-old children (n 2222) in Switzerland in 2007, with standard errors represented by vertical bars. *Prevalence was significantly different from that in the central eastern region (P < 0·05); †prevalence was significantly different from that in the smaller communities (P < 0·05)

, >100 000 inhabitants) differences in the prevalences of underweight, overweight and obesity in a national sample of 6- to 13-year-old children (n 2222) in Switzerland in 2007, with standard errors represented by vertical bars. *Prevalence was significantly different from that in the central eastern region (P < 0·05); †prevalence was significantly different from that in the smaller communities (P < 0·05)

The prevalences of underweight, overweight and obesity for both time points are displayed in Table 3. The prevalence of underweight has not changed significantly over the 5 years, but the prevalences of overweight and obesity have decreased. For boys, the decrease in overweight was not significant (P = 0·37), but for girls it was (P < 0·01). For obesity, the decrease was significant in both boys (P = 0·049) and girls (P < 0·01).

Table 3 Prevalence of underweight, overweight and obesity in children in Switzerland in the national studies from 2002 and 2007 by sex using the CDC BMI reference criteria

CDC, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

CDC BMI reference criteriaReference Ogden, Kuczmarski, Flegal, Mei, Guo, Wei, Grummer-Strawn, Curtin, Roche and Johnson(13): underweight, BMI-for-age <5th percentile; overweight, BMI-for-age ≥85th and <95th percentile; obese, BMI-for-age ≥95th percentile; overweight + obesity, all children with BMI-for-age ≥85th percentile.

*Mean values were significantly different from those in 2002 (z test): P < 0·05.

About 60 % of the schools responded to the questionnaire about measures being taken to reduce overweight and obesity. Of these, 83 % said they had initiated a programme emphasizing physical activity and 75 % said they had taken action to encourage healthy eating. The actions taken varied widely; from very basic information (such as advising children to walk or cycle to school and bring healthy snacks to school) to more extensive projects lasting weeks or the entire school year.

Discussion

Compared with the national study conducted in the year 2002(Reference Zimmermann, Gubeli, Puntener and Molinari10, Reference Zimmermann, Gubeli, Puntener and Molinari11), the present data from 2007 show a decrease in the prevalence of overweight and obesity in both boys and girls. Even though the difference is significant in all but overweight boys, we have to be careful with the interpretation. The procedure for the selection of the schools asked to participate in the study was the same as for the 2002 study, only using more recent census data provided by the Federal Statistical Office. Further, it was ensured in both studies that the sampling scheme was followed very closely. In 2007 it was possible to recruit the appropriate number of schools from each cluster and stratum, while in 2002 three schools were missing. However, those three missing schools were all in different regions and did not represent the same demographic stratum either. Thus, the two samples should be comparable. Although the mean age of the children studied in 2007 was statistically significantly greater than the children studied in 2002, the mean difference was small (0·2 years) and is unlikely to be relevant for the outcomes of the study, particularly because the prevalences were calculated based on age-specific cut-off points. This difference is likely due to the fact that the sampling period was slightly longer in 2007 compared with 2002. The response rate of the children in 2007 was 73 %, slightly below the response rate of 2002 (76 %). These 3 % would most probably not influence the result greatly if the children who declined participation were equally distributed over the whole range of body weight; whether this is the case is difficult to judge. Public awareness of the problem of childhood obesity has increased over the past 5 years and this may have caused more parents to consent for their children to participate or, alternatively, may have led some to exclude their overweight children to avoid stigmatization.

Up to 2003, all European countries where data were available had shown increasing prevalences of childhood overweight(Reference Branca, Nikogosian and Lobstein1). However, recent reports from several European countries(Reference Peneau, Salanave and Maillard-Teyssier5–Reference Salanave, Peneau, Rolland-Cachera, Hercberg and Castetbon9) and the USA(Reference Ogden, Carroll and Flegal14) show that childhood obesity prevalences may be levelling off or decreasing slightly over the past few years. In two studies in French children – one sample between 6 and 15 years of age, the other between 7 and 9 years – a stabilization of childhood overweight was observed between 1998 and 2006 and 2000 and 2007, respectively, with a higher prevalence remaining in disadvantaged groups(Reference Peneau, Salanave and Maillard-Teyssier5, Reference Salanave, Peneau, Rolland-Cachera, Hercberg and Castetbon9). Similar trends of stabilization were found in a study analysing data between 1999 and 2003 in 10-year-old children in Stockholm County, Sweden(Reference Sundblom, Petzold, Rasmussen, Callmer and Lissner7); while in Göteborg, Sweden, similar to our study, the prevalence of overweight decreased in 10-year-old girls and was stable in 10-year-old boys between 2000–1 and 2004–5(Reference Sjoberg, Lissner, Albertsson-Wikland and Marild6).

Compared with 2002, in 2007 we found significant differences in the rates of childhood obesity when comparing communities with populations below and above 100 000 inhabitants. In general, comparing the answers received from the schools with regard to measures taken to combat overweight or obesity, we could not discern differences between those from different sized communities. However, it is possible that programmes to increase physical activity have had a bigger impact in more rural areas where children likely have more opportunity to move and play outside, compared with the bigger cities. None of the recent studies reporting a stabilization or decrease in the prevalence of childhood obesity(Reference Peneau, Salanave and Maillard-Teyssier5–Reference Salanave, Peneau, Rolland-Cachera, Hercberg and Castetbon9, Reference Ogden, Carroll and Flegal14) have analysed their data for demographic changes. The French and one of the Swedish studies(Reference Peneau, Salanave and Maillard-Teyssier5, Reference Sundblom, Petzold, Rasmussen, Callmer and Lissner7, Reference Salanave, Peneau, Rolland-Cachera, Hercberg and Castetbon9) reported that lower socio-economic groups showed a higher overweight prevalence and the US study(Reference Ogden, Carroll and Flegal14) reported ethnic differences in adiposity. However, we do not have information on either socio-economic or ethnic differences in our sample.

The reported change in paediatric obesity is likely due to an increasing awareness of the public health importance of this topic over the past few years. As a result, a whole range of programmes and projects has been designed and conducted to counteract the alarming increase shown. Although most programmes were rather small and either school- or community-based and not conducted nationwide, it may well be that the accumulation of all these programmes has resulted in an overall decrease or at least a stabilization of the prevalence of overweight and obesity in children in Switzerland.

It would go beyond the aim of the present paper to review all the programmes and projects that have been conducted in Switzerland in the past few years; however, a short overview of a selection is given hereafter. First, there are several different clinics as well as other organizations that offer in- or outpatient treatment programmes for obese children and adolescents. Moreover, an important player in the field of overweight prevention and intervention in Switzerland is Suisse Balance, a nationwide initiative financed through the Federal Office of Public Health and the foundation ‘Gesundheitsförderung Schweiz’, which on its part is sponsored by the cantons of Switzerland as well as different insurance companies. Suisse Balance supports projects and initiatives to promote a healthy lifestyle, more physical activity and well-balanced nutrition. Several projects concentrating on nutrition and physical activity in children have already been launched and some even completed (www.suissebalance.ch). A wide variety of other, mostly smaller programmes and projects is ongoing. A variety of such projects can be found on the website of the ‘Schweizerische Netzwerk gesundheitsfördernder Schulen’ (http://www.gesunde-schulen.ch/html/projektbrowser.html).

Judging from the questionnaires returned from the participating schools, where over 80 % reported emphasizing physical activity and 75 % healthy eating, the motivation of the schools to do something seems to be rather high. However, as those were all small programmes not conducted under scientific supervision, almost none of them have been validated with respect to their actual impact on the children’s weight. We cannot therefore prove any causal effect of these programmes on the decrease in overweight and obesity shown. Further, as the aim of many of the programmes was to change the children’s behaviour over the long term in a way that promotes physical activity and/or teaches the children about a healthy diet, it is even more difficult to evaluate the effect in numbers over a rather short time period. In France, the stabilization of the prevalence of childhood obesity observed in 2006 and 2007, respectively, followed the launch of a Nutrition and Health National Programme established by the government(Reference Peneau, Salanave and Maillard-Teyssier5, Reference Salanave, Peneau, Rolland-Cachera, Hercberg and Castetbon9); however, even there it is not possible to prove a causal relationship between this programme and the stabilization. Similar to Switzerland, no national or regional programme aiming at a reduction in childhood obesity preceded the stabilization of the situation in Sweden, but the increased public awareness of the problem since publication of earlier results is mentioned as a possible factor(Reference Sjoberg, Lissner, Albertsson-Wikland and Marild6).

Another potentially important factor to control childhood obesity, besides the action being taken by schools and communities, is the relatively strict regulation of Swiss television advertising to children and adolescents. The Swiss Radio and Television Law has included regulations for the protection of children and adolescents from advertising since 1991. However, in the beginning those regulations were not very specific. Since 1997, any advertisement which plays on the credulity of children or the lack of experience of adolescents is prohibited. Since the beginning of 2007, it is now no longer allowed to interrupt children’s television programmes by commercials. However, these regulations are not likely to be responsible for the current improvement in the childhood overweight prevalence unless it is assumed that the changes made in 1997 only showed their effects more than 5 years later. But even in general programming, no more than 15 % of daily airtime can be used for advertisements. This limits children’s exposure to advertising for energy-dense foods, which in the USA has been shown to be a risk factor for weight gain(Reference Coon and Tucker15).

Thus, considerable action has been taken in order to combat overweight and obesity in Swiss schoolchildren; this may have contributed to our findings of a lower prevalence. Our findings suggest the increasing prevalence of childhood overweight and obesity in Switzerland until 2002 may be coming under control, although nearly one in six children remains overweight or obese. Thus, treatment programmes should continue to focus on severely obese children and try to reach as many of them as possible, while prevention programmes should focus on the general population. Monitoring and evaluation of the programmes introduced in Switzerland should help to determine which approaches are most effective. However, it seems to be essential to combine healthy eating with increased physical activity in enjoyable ways so that children continue to follow them in their daily routines after they finish school.

Acknowledgements

The study was financed by the Swiss Federal Office of Public Health. None of the authors had personal or financial conflict of interests regarding the current paper. Each of the authors contributed to the study design and data analysis. Data collection was done by I.A., R.S.A. and M.K. The first draft of the paper was written by I.A. and edited by the other authors. The authors would like to thank the teachers and children at the participating schools for their cooperation.