Social ecological models of health suggest that community food environments must be structured to support healthy eating behaviours to effectively prevent chronic disease( Reference Brownson, Haire-Joshu and Luke 1 – Reference Frieden 4 ). However, a growing body of research has documented disparities in access to healthy foods throughout the USA( Reference Larson, Story and Nelson 5 , Reference Caspi, Sorensen and Subramanian 6 ). Neighbourhoods with predominantly low-income and racial and ethnic minority residents tend to have limited access to retailers of healthier food options, such as full-service supermarkets( Reference Moore and Diez Roux 7 , Reference Zenk, Schulz and Israel 8 ), and are instead disproportionately served by retailers of energy-dense processed foods, including fast-food outlets( Reference Fleischhacker, Evenson and Rodriguez 9 ).

A growing focus on increasing access to healthy foods by opening new retailers in underserved communities is reflected in both national public health objectives and large-scale healthy food financing initiatives. For example, Healthy People 2020 includes an objective to increase the proportion of Americans who have access to a food outlet that sells foods recommended by federal dietary guidelines(10). In 2010, the US Departments of Agriculture, Treasury, and Health and Human Services announced the Healthy Food Financing Initiative, which funds the development of new retailers of healthy foods in underserved communities throughout the country( 11 ). Additional public–private partnerships, such as the Pennsylvania Fresh Food Financing Initiative, the New York Fresh Retail Expansion to Support Health (FRESH) programme, the California FreshWorks Fund and the New Orleans Fresh Food Retailer Initiative( 12 – 15 ), are emerging as models for improving local food environments. Among other activities, these initiatives incentivize the development of supermarkets and grocery stores in limited-access neighbourhoods through zoning reforms, loans and grants.

Introducing new retailers of healthy foods into limited-access communities is an intuitively appealing intervention strategy, and although multiple evaluations of such initiatives have been published, no known systematic reviews have synthesized this body of research. The present systematic review aims to answer the following research questions:

-

1. What types of retailers of fruits and vegetables have been evaluated and in what settings?

-

2. What methods have been used to evaluate these initiatives?

-

3. To what extent have these initiatives impacted fruit and vegetable consumption among adults?

Fruit and vegetable consumption among adults was identified as the outcome of interest because this was a commonly used outcome in relevant studies, as well as the broader epidemiological literature( Reference Caspi, Sorensen and Subramanian 6 ).

Methods

References were retrieved from MEDLINE, EMBASE and Web of Science databases from inception through November 2015 using a search strategy adapted from a previous systematic review about spatial access to food retailers and diet( Reference Caspi, Sorensen and Subramanian 6 ). English-language references that contained at least one keyword related to the following three domains were retrieved: (i) food retailers (food retail*, food store*, food outlet*, grocer*, supermarket*, farmers market*, farm stand); (ii) the environment (access*, availab*, afford*, environment*, loca*, neighborhood*, neighbourhood*, communit*, urban, or rural); and (iii) diet (diet, fruit*, vegetable*, nutriti*, consum*, intake).

Two investigators (R.C.W. and I.G.R.) identified candidate articles by independently reviewing the titles of all references for eligibility, referring to the abstracts for additional details when a decision could not be made based on the title alone. References were excluded if they: (i) were not about the general topic area of access to healthy foods as a determinant of dietary behaviour; (ii) were not about an initiative intended to increase access to healthy foods; or (iii) were not about the introduction of a new retailer of healthy foods into a community. Additional references were identified by hand-searching the bibliographies of the candidate articles and entering their bibliographic information into Google Scholar to identify more recent articles that had cited them.

Once the pool of candidate articles was finalized, all were reviewed in full text. In instances in which multiple publications resulted from the same parent study (e.g. a baseline paper describing the retailer and one or more outcome evaluations), we grouped articles by parent study and determined eligibility at the study level. Studies were excluded if they were found to meet the exclusion criteria described previously, if the evaluation did not include change in fruit and vegetable consumption as an outcome, or if it focused exclusively on dietary change among children. Studies that focused exclusively on children were excluded because the causal mechanism through which the opening of a new retailer of healthy foods would impact diet was expected to differ for this group.

The data abstraction form was developed based on the Transparent Reporting of Evaluations with Nonrandomized Designs (TREND) statement and piloted with a sample of articles. Two investigators (R.C.W. and I.G.R.) independently abstracted the following information from all articles included in the review: bibliographic information, key characteristics of the retailer described in the article (e.g. type, location, date opened, setting, population served, etc.), the methods used to evaluate the retailer (e.g. sampling methods, sample size, data collection procedures, outcome measures, etc.) and its impact on fruit and vegetable consumption; discrepancies were resolved by consensus. For studies that used repeated measures designs, mean differences in fruit and vegetable consumption were the principal summary measure. Nine corresponding authors were contacted by email for additional information about the methods or results (89 % response rate).

Studies were the unit of analysis for the present review. Due to the heterogeneity in methods used, meta-analysis was not possible. Analysis involved organizing studies according to the type of evaluation design used and using descriptive statistics, including frequencies and percentages, to describe the types of retailers that were assessed, the methods used to evaluate them and change in fruit and vegetable consumption. In many cases, the number of references exceeds the number of studies because multiple publications resulted from individual studies.

Results

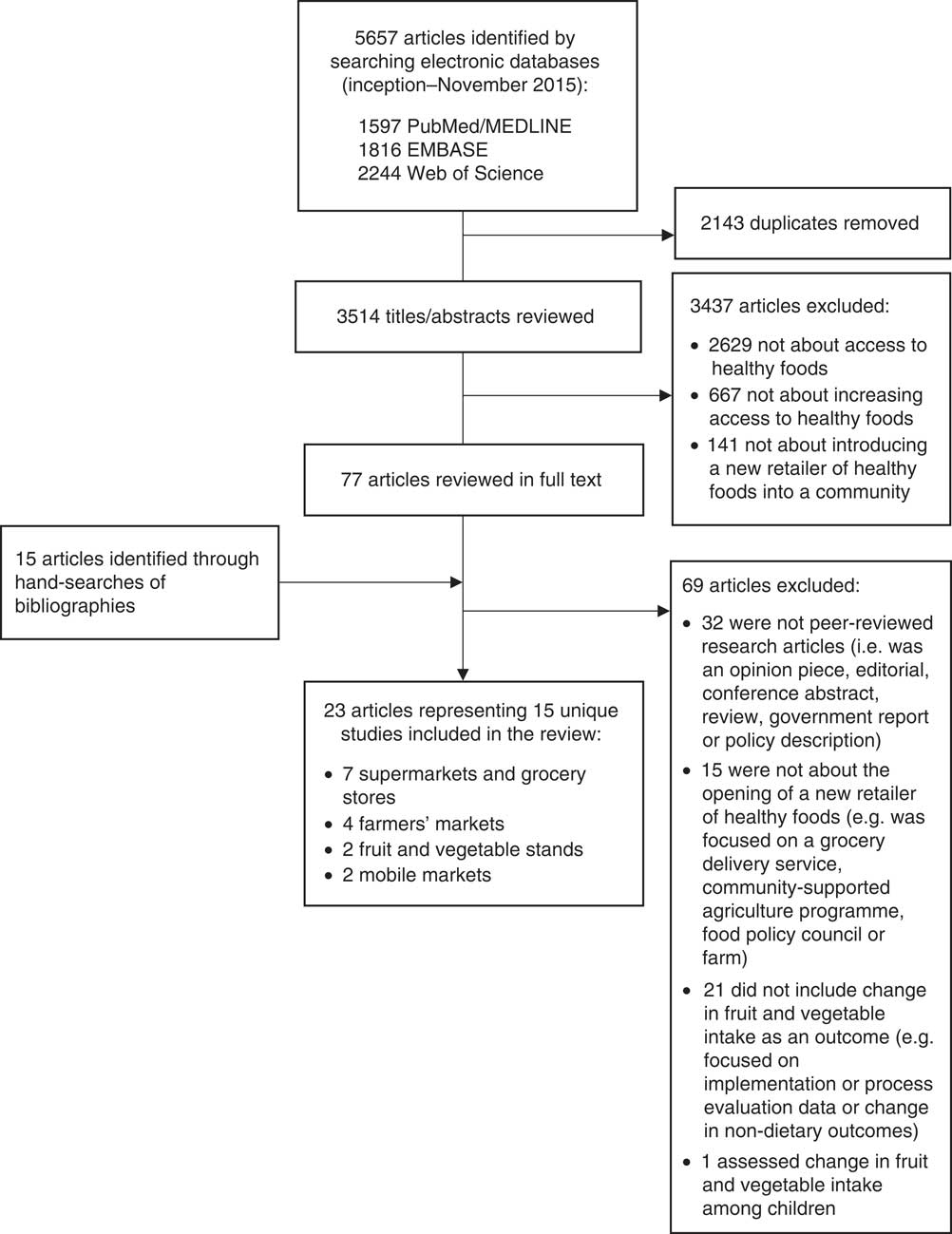

Of the 5657 references retrieved through keyword searches, 3514 were unique articles and 3437 were excluded based on the title/abstract review (Fig. 1). The remaining seventy-seven candidate articles and fifteen additional articles identified through hand-searching were reviewed in full text to assess eligibility. Of these, sixty-nine articles were excluded. The most common reasons for exclusion were that the article was not a peer-reviewed original research article (i.e. was an opinion piece, editorial, letter to the editor, conference abstract, review, government report or policy description; n 32); was not about the opening of a new retailer of healthy foods (e.g. was focused on a grocery delivery service, community-supported agriculture programme, food policy council or farm; n 15); or did not assess change in fruit and vegetable consumption among adults as part of the evaluation (n 22). The twenty-two articles in this latter category commonly reported implementation or process evaluation data (e.g. sales volume, demographic characteristics of shoppers, satisfaction with the retailer, etc.) or changes to other non-dietary outcomes (e.g. customers’ shopping patterns, access to healthy foods, etc.). The present review focuses on the remaining twenty-three articles, which represented fifteen unique studies.

Fig. 1 Flow diagram depicting article selection for inclusion in the present systematic review on the dietary impact of introducing new retailers of fruits and vegetables into a community

Description of retailers and settings

As shown in Fig. 1, the types of retailers assessed included supermarkets and grocery stores (n 7)( Reference Cummins, Findlay and Higgins 16 – Reference Sadler, Gilliland and Arku 30 ), farmers’ markets (n 4)( Reference Freedman 31 – Reference Payet, Gilles and Howat 34 ), fruit and vegetable stands or markets (n 2)( Reference Woodruff, Coleman and Hermstad 35 , Reference Evans, Jennings and Smiley 36 ), and mobile markets (n 2)( Reference Abusabha, Namjoshi and Klein 37 , Reference Jennings, Cassidy and Winters 38 ). Supermarkets and grocery stores tended to be subsidized through public–private partnerships, including the Healthy Food Financing Initiative (n 2)( Reference Cummins, Flint and Matthews 19 , Reference Dubowitz, Ghosh-Dastidar and Cohen 22 , Reference Dubowitz, Ncube and Leuschner 23 ) and the New York Food Retail Expansion to Support Health (FRESH) initiative (n 1)( Reference Elbel, Mijanovich and Kiszko 20 , Reference Elbel, Moran and Dixon 21 ), or were aligned with broader corporate initiatives to promote economic development or open supermarkets in deprived areas (n 2)( Reference Wrigley, Warm and Margetts 24 – Reference Gill and Rudkin 27 , Reference Sadler, Gilliland and Arku 29 , Reference Sadler, Gilliland and Arku 30 ). The smaller retailers, such as farmers’ markets, fruit and vegetable stands or markets, and mobile markets, tended to report community involvement in planning or operating the retailer, including having a community advisory board, collaborating with other local organization to implement the retailer, or that the project used a community-based participatory approach (n 7)( Reference Freedman 31 – Reference Evans, Jennings and Smiley 36 , Reference Jennings, Cassidy and Winters 38 ).

Most of the retailers were located in low-income and/or economically deprived communities (n 13)( Reference Cummins, Findlay and Higgins 16 – Reference Sadler, Gilliland and Arku 30 , Reference Freedman, Choi and Hurley 32 , Reference Ruelas, Iverson and Kiekel 33 , Reference Woodruff, Coleman and Hermstad 35 – Reference Jennings, Cassidy and Winters 38 ) that had limited access to healthy foods (n 12)( Reference Cummins, Findlay and Higgins 16 – Reference Freedman 31 , Reference Ruelas, Iverson and Kiekel 33 – Reference Evans, Jennings and Smiley 36 ) in the USA (n 11)( Reference Cummins, Flint and Matthews 19 – Reference Dubowitz, Ncube and Leuschner 23 , Reference Wang, MacLeod and Steadman 28 – Reference Ruelas, Iverson and Kiekel 33 , Reference Woodruff, Coleman and Hermstad 35 – Reference Abusabha, Namjoshi and Klein 37 ), the UK (n 3)( Reference Cummins, Findlay and Higgins 16 – Reference Cummins, Petticrew and Higgins 18 , Reference Wrigley, Warm and Margetts 24 – Reference Gill and Rudkin 27 , Reference Jennings, Cassidy and Winters 38 ) or Australia (n 1)( Reference Payet, Gilles and Howat 34 ). Many studies also described the communities in which the new retailer opened as comprised of predominantly racial or ethnic minority residents (n 7)( Reference Cummins, Flint and Matthews 19 – Reference Dubowitz, Ncube and Leuschner 23 , Reference Sadler, Gilliland and Arku 29 – Reference Ruelas, Iverson and Kiekel 33 ). Most retailers were located in general community settings (n 11)( Reference Cummins, Findlay and Higgins 16 – Reference Freedman 31 , Reference Ruelas, Iverson and Kiekel 33 , Reference Payet, Gilles and Howat 34 , Reference Jennings, Cassidy and Winters 38 ), although some farmers’ markets, fruit and vegetable stands, and mobile markets operated at local community organizations (n 3)( Reference Woodruff, Coleman and Hermstad 35 – Reference Abusabha, Namjoshi and Klein 37 ), residential housing complexes (n 2)( Reference Woodruff, Coleman and Hermstad 35 , Reference Abusabha, Namjoshi and Klein 37 ) and health centres (n 1)( Reference Freedman, Choi and Hurley 32 ).

Evaluation methods

A variety of methods were used to evaluate the impact of the retailer on fruit and vegetable intake. Retailers were evaluated using post-test only designs (n 4)( Reference Wang, MacLeod and Steadman 28 , Reference Ruelas, Iverson and Kiekel 33 – Reference Woodruff, Coleman and Hermstad 35 ), repeated cross-sectional designs (n 4)( Reference Elbel, Mijanovich and Kiszko 20 , Reference Elbel, Moran and Dixon 21 , Reference Sadler, Gilliland and Arku 29 – Reference Freedman 31 , Reference Jennings, Cassidy and Winters 38 ) and repeated measures designs (n 7; Table 1)( Reference Cummins, Findlay and Higgins 16 – Reference Cummins, Flint and Matthews 19 , Reference Dubowitz, Ghosh-Dastidar and Cohen 22 – Reference Gill and Rudkin 27 , Reference Freedman, Choi and Hurley 32 , Reference Evans, Jennings and Smiley 36 , Reference Abusabha, Namjoshi and Klein 37 ). Studies assessed the impact of the retailer on fruit and vegetable consumption approximately six months (n 7)( Reference Wrigley, Warm and Margetts 24 – Reference Wang, MacLeod and Steadman 28 , Reference Freedman 31 , Reference Freedman, Choi and Hurley 32 , Reference Woodruff, Coleman and Hermstad 35 – Reference Abusabha, Namjoshi and Klein 37 ), one year (n 5)( Reference Cummins, Findlay and Higgins 16 – Reference Dubowitz, Ncube and Leuschner 23 , Reference Sadler, Gilliland and Arku 29 , Reference Sadler, Gilliland and Arku 30 ) or two years (n 2)( Reference Ruelas, Iverson and Kiekel 33 , Reference Jennings, Cassidy and Winters 38 ) after the retailer opened, or at multiple follow-up intervals( Reference Ruelas, Iverson and Kiekel 33 ).

Table 1 Methodological summary of evaluations of the opening of a retailer of healthy foods on fruit and vegetable intake among adults (N 15)

NR, not reported; BRFSS, Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System; NCI FVS, National Cancer Institute Fruit and Vegetable Intake Screener.

* Calculated by hand using information provided in the article.

Eight studies used convenience sampling( Reference Elbel, Mijanovich and Kiszko 20 , Reference Elbel, Moran and Dixon 21 , Reference Wang, MacLeod and Steadman 28 , Reference Freedman 31 , Reference Ruelas, Iverson and Kiekel 33 – Reference Woodruff, Coleman and Hermstad 35 , Reference Abusabha, Namjoshi and Klein 37 , Reference Jennings, Cassidy and Winters 38 ) and six used probability sampling methods( Reference Cummins, Findlay and Higgins 16 – Reference Cummins, Flint and Matthews 19 , Reference Dubowitz, Ghosh-Dastidar and Cohen 22 , Reference Dubowitz, Ncube and Leuschner 23 , Reference Sadler, Gilliland and Arku 29 , Reference Sadler, Gilliland and Arku 30 , Reference Freedman, Choi and Hurley 32 , Reference Evans, Jennings and Smiley 36 ). The sampling method could not be determined for one study( Reference Wrigley, Warm and Margetts 24 – Reference Gill and Rudkin 27 ). Six studies sampled shoppers at the new retailer( Reference Freedman 31 , Reference Ruelas, Iverson and Kiekel 33 – Reference Woodruff, Coleman and Hermstad 35 , Reference Abusabha, Namjoshi and Klein 37 , Reference Jennings, Cassidy and Winters 38 ) and three sampled residents of the neighbourhood where the new retailer opened( Reference Wrigley, Warm and Margetts 24 – Reference Wang, MacLeod and Steadman 28 , Reference Evans, Jennings and Smiley 36 ). An additional five studies sampled from both residents of the neighbourhood where the new retailer opened and a comparison neighbourhood that did not receive a new retailer( Reference Cummins, Findlay and Higgins 16 – Reference Dubowitz, Ncube and Leuschner 23 , Reference Sadler, Gilliland and Arku 29 , Reference Sadler, Gilliland and Arku 30 ). One study sampled patients at a health clinic where the retailer was located( Reference Freedman, Choi and Hurley 32 ). Sample sizes ranged widely.

Outcome measures included retrospective items asking participants to what extent their fruit and vegetable intake changed over time (n 4)( Reference Wang, MacLeod and Steadman 28 , Reference Ruelas, Iverson and Kiekel 33 – Reference Woodruff, Coleman and Hermstad 35 ), two-item screeners assessing usual daily intake of fruits and vegetables (n 3)( Reference Cummins, Flint and Matthews 19 , Reference Freedman 31 , Reference Jennings, Cassidy and Winters 38 ), brief fruit and vegetable intake screeners or FFQ (n 6)( Reference Cummins, Findlay and Higgins 16 – Reference Cummins, Petticrew and Higgins 18 , Reference Elbel, Mijanovich and Kiszko 20 , Reference Elbel, Moran and Dixon 21 , Reference Sadler, Gilliland and Arku 29 , Reference Sadler, Gilliland and Arku 30 , Reference Freedman, Choi and Hurley 32 , Reference Evans, Jennings and Smiley 36 , Reference Abusabha, Namjoshi and Klein 37 ), or dietary recalls (n 3)( Reference Elbel, Mijanovich and Kiszko 20 – Reference Gill and Rudkin 27 ). One study used multiple methods of assessing fruit and vegetable intake( Reference Elbel, Mijanovich and Kiszko 20 , Reference Elbel, Moran and Dixon 21 ).

Post-test only designs

Methodological overview

Four studies used post-test only designs to assess the dietary impact of the new retailer (Table 1). In these studies, cross-sectional surveys were administered to participants four months to two-and-a-half years after the opening of the retailer( Reference Wang, MacLeod and Steadman 28 , Reference Ruelas, Iverson and Kiekel 33 – Reference Woodruff, Coleman and Hermstad 35 ). All studies focused on dietary change among a convenience sample of adults who were either shoppers at the retailer( Reference Ruelas, Iverson and Kiekel 33 – Reference Woodruff, Coleman and Hermstad 35 ) or lived in the neighbourhood where the new retailer opened for business( Reference Wang, MacLeod and Steadman 28 ). All of these studies used a retrospective approach to measure change in fruit and vegetable intake by asking participants to report changes in fruit or vegetable consumption as a result of shopping at the retailer( Reference Ruelas, Iverson and Kiekel 33 – Reference Woodruff, Coleman and Hermstad 35 ) or generally within the past year( Reference Wang, MacLeod and Steadman 28 ).

Change in fruit and vegetable intake

Of the studies that surveyed shoppers at the retailer, most respondents reported that they were eating more fruits and/or vegetables at the time of the survey( Reference Ruelas, Iverson and Kiekel 33 – Reference Woodruff, Coleman and Hermstad 35 ). For example, of 100 shoppers at a farmers’ market in Carnarvon, Western Australia who were surveyed approximately two-and-a-half years after its opening, 71 % reported that they were eating more fruits and vegetables since they started shopping there( Reference Payet, Gilles and Howat 34 ). A survey of 100 returning customers who were surveyed approximately four months after the opening of a fruit and vegetable stand in Cobb County, Georgia, USA reported that they were eating more vegetables (65 %) and fruit (55 %) as a result of the market( Reference Woodruff, Coleman and Hermstad 35 ). Another survey administered to shoppers at two farmers’ markets in Los Angeles, California, USA between five months and two years after the markets opened reported that 97–98 % agreed or strongly agreed that they were eating more fruits and vegetables as a result of the market( Reference Ruelas, Iverson and Kiekel 33 ). By contrast, the one study that assessed the impact of a new grocery store that opened in an unnamed city in California, USA on the dietary behaviours of residents of the neighbourhood where it opened (regardless of whether participants shopped there) found smaller changes in fruit and vegetable consumption. Relatively few respondents who lived 3·2 km (2 miles) from the new grocery store reported increased vegetable (10·3 %) or fruit (9 %, n 73) consumption over the previous year( Reference Wang, MacLeod and Steadman 28 ).

Repeated cross-sectional designs

Methodological overview

Four studies used repeated cross-sectional surveys at baseline and follow-up to assess the dietary impact of the new retailer (Table 1). Two studies used a convenience sample of market shoppers( Reference Freedman 31 , Reference Jennings, Cassidy and Winters 38 ); one used a random sample of households with landlines located within 2000 m of the store site and a nearby comparison neighbourhood( Reference Sadler, Gilliland and Arku 29 , Reference Sadler, Gilliland and Arku 30 ); and another recruited participants from busy intersections in the neighbourhood where the retailer opened, as well as a nearby comparison neighbourhood( Reference Elbel, Mijanovich and Kiszko 20 , Reference Elbel, Moran and Dixon 21 ). Measurement approaches included using a two-item fruit and vegetable intake screener( Reference Freedman 31 , Reference Jennings, Cassidy and Winters 38 ); the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) screener( Reference Sadler, Gilliland and Arku 29 , Reference Sadler, Gilliland and Arku 30 ); or a combination of a brief screener and a single 24 h dietary recall( Reference Elbel, Mijanovich and Kiszko 20 , Reference Elbel, Moran and Dixon 21 ).

Change in fruit and vegetable intake

Results from studies in this category were difficult to summarize due to the heterogeneity in methodological approaches. For example, one evaluation of a farmers’ market in Nashville, Tennessee, USA found that shoppers sampled at 1- and 2-month follow-ups reported higher levels of fruit and vegetable consumption relative to a different sample of shoppers sampled at baseline( Reference Freedman 31 ). However, these results were reported graphically, and no estimates of mean intake were presented to quantify the difference in mean intake between the samples over time( Reference Freedman 31 ). A different study of a convenience sample of shoppers at a mobile market in the UK found that those sampled at follow-up reported higher mean fruit and vegetable intake at follow-up than the baseline sample (mean difference=1·16 portions, 95 % CI 0·83, 1·48, P<0·0001)( Reference Jennings, Cassidy and Winters 38 ).

Two studies assessed community-level dietary change among residents of the neighbourhood that received the new retailer relative to those who lived in a comparison neighbourhood( Reference Elbel, Mijanovich and Kiszko 20 , Reference Elbel, Moran and Dixon 21 , Reference Sadler, Gilliland and Arku 29 , Reference Sadler, Gilliland and Arku 30 ). One of these studies conducted telephone surveys before and 12 months after a grocery store opened in Flint, Michigan, USA among a random sample of households located within 2000 m of the new store and those located in a comparison neighbourhood. That study found that mean intake of fruits and vegetables was the same among the baseline and follow-up samples in the intervention neighbourhood (mean intake=2·6 servings/d among samples at both time points), although mean intake was higher among the comparison neighbourhood residents in the follow-up sample relative to the baseline sample (mean intake=2·5 servings/d at baseline, mean intake=2·9 servings/d at follow-up)( Reference Sadler, Gilliland and Arku 29 , Reference Sadler, Gilliland and Arku 30 ). Information about the precision and statistical significance of these estimates is unavailable.

Another study conducted surveys among adults recruited from busy intersections located in a neighbourhood that received a new supermarket and a comparison neighbourhood in the Bronx, New York City, USA( Reference Elbel, Mijanovich and Kiszko 20 , Reference Elbel, Moran and Dixon 21 ). Surveys were administered at baseline, 1–5 months and 13–17 months after the supermarket opened, and included two different methods of assessing fruit and vegetable intake. Results from the brief fruit and vegetable intake screener indicated among both intervention and comparison neighbourhood residents that mean fruit and vegetable intake was highest at baseline relative to either follow-up time point (e.g. mean change in vegetable consumption=−0·1 daily servings among intervention neighbourhood sample v. 0·0 among comparison neighbourhood sample). Results from the 24 h dietary recalls showed a different pattern of higher fruit and vegetable consumption at follow-up relative to baseline in both groups, although greater improvements among those sampled from the comparison community (e.g. mean change in vegetable consumption of 0·21 daily servings among intervention neighbourhood sample v. 0·58 daily servings among comparison neighbourhood sample)( Reference Elbel, Mijanovich and Kiszko 20 , Reference Elbel, Moran and Dixon 21 ).

Repeated measures designs

Methodological overview

Seven studies used repeated measures to assess the dietary impact of the new retailer (Table 1). All of these studies collected data from participants at baseline and at either one (n 6)( Reference Cummins, Findlay and Higgins 16 – Reference Cummins, Flint and Matthews 19 , Reference Dubowitz, Ghosh-Dastidar and Cohen 22 – Reference Wrigley, Warm and Margetts 26 , Reference Evans, Jennings and Smiley 36 , Reference Abusabha, Namjoshi and Klein 37 ) or two (n 1)( Reference Freedman, Choi and Hurley 32 ) follow-up time points. The majority of these studies used probability sampling methods to recruit participants( Reference Cummins, Findlay and Higgins 16 – Reference Cummins, Flint and Matthews 19 , Reference Dubowitz, Ghosh-Dastidar and Cohen 22 , Reference Dubowitz, Ncube and Leuschner 23 , Reference Freedman, Choi and Hurley 32 , Reference Evans, Jennings and Smiley 36 ), although one used convenience sampling methods( Reference Abusabha, Namjoshi and Klein 37 ) and the approach used by another could not be determined( Reference Wrigley, Warm and Margetts 24 – Reference Gill and Rudkin 27 ). One study recruited shoppers at the new retailer( Reference Abusabha, Namjoshi and Klein 37 ), two recruited residents of the neighbourhood where the new retailer opened( Reference Wrigley, Warm and Margetts 24 – Reference Wrigley, Warm and Margetts 26 , Reference Evans, Jennings and Smiley 36 ) and three recruited residents of both the intervention neighbourhood and a nearby comparison neighbourhood( Reference Cummins, Findlay and Higgins 16 – Reference Cummins, Flint and Matthews 19 , Reference Dubowitz, Ghosh-Dastidar and Cohen 22 , Reference Dubowitz, Ncube and Leuschner 23 ). One study recruited patients from the clinic where the new retailer opened for business( Reference Freedman, Choi and Hurley 32 ). Studies in this category measured change in fruit and vegetable consumption using a two-item screener asking about usual intake of fruits and vegetables per day (n 1)( Reference Cummins, Flint and Matthews 19 ), brief screeners or FFQ (e.g. BRFSS( Reference Abusabha, Namjoshi and Klein 37 ), the National Cancer Institute Fruit and Vegetable Screener( Reference Freedman, Choi and Hurley 32 , Reference Evans, Jennings and Smiley 36 ) or the Block Food Frequency Questionnaire( Reference Cummins, Findlay and Higgins 16 – Reference Cummins, Petticrew and Higgins 18 ); n 4), a 7 d food diary (n 1)( Reference Wrigley, Warm and Margetts 24 – Reference Wrigley, Warm and Margetts 26 ) or multiple 24 h dietary recalls (n 1)( Reference Dubowitz, Ghosh-Dastidar and Cohen 22 , Reference Dubowitz, Ncube and Leuschner 23 ).

Change in fruit and vegetable intake

With one exception( Reference Cummins, Flint and Matthews 19 ), all studies in this category reported mean within-person change in fruit and vegetable intake from baseline to follow-up. Depending on the sampling strategy used, these results could be presented in three ways: (i) change in fruit and vegetable intake among shoppers at the new retailer; (ii) change in fruit and vegetable intake among residents of the neighbourhood where the new retailer opened; or (iii) the differencein-differences comparing mean change in fruit and vegetable intake among residents of the intervention v. comparison neighbourhood (Table 2).

Table 2 Effect sizes of the impact of the opening of a new retailer of healthy foods on within-person change in fruit and vegetable consumption among adults (n 6)

BRFSS, Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System; NCI FVS, National Cancer Institute Fruit and Vegetable Intake Screener; NR, not reported.

* Result was calculated by hand based on information provided in the article.

Of the five studies that reported change in fruit and vegetable intake among shoppers at the new retailer, most reported modest, albeit not always statistically significant, increases in mean intake (n 4)( Reference Wrigley, Warm and Margetts 24 – Reference Wrigley, Warm and Margetts 26 , Reference Freedman, Choi and Hurley 32 , Reference Abusabha, Namjoshi and Klein 37 ), although one study reported a small decrease( Reference Dubowitz, Ghosh-Dastidar and Cohen 22 , Reference Dubowitz, Ncube and Leuschner 23 ). For example, one study of forty-three shoppers at a mobile market in Troy, New York, USA reported a statistically insignificant 0·45-serving increase in daily fruit and vegetable intake six months after the market expanded its route to serve additional stops (95 % CI −0·23, 1·14)( Reference Abusabha, Namjoshi and Klein 37 ). Another study of forty-one diabetic adults who shopped at a farmers’ market in a health clinic in rural South Carolina, USA reported a statistically insignificant 0·54-serving increase in fruit and vegetable intake five months after it opened (95 % CI −1·14, 2·23)( Reference Freedman, Choi and Hurley 32 ). Another study of 276 shoppers at a new supermarket in Leeds, UK reported a statistically significant 0·23-portion increase in fruit and vegetable intake six to seven months after it opened (P=0·034)( Reference Wrigley, Warm and Margetts 24 – Reference Gill and Rudkin 27 ). However, a study of 368 shoppers at a new supermarket in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA reported a statistically insignificant −0·32-serving decrease in intake seven to fourteen months after it opened( Reference Dubowitz, Ghosh-Dastidar and Cohen 22 , Reference Dubowitz, Ncube and Leuschner 23 ).

Results were less consistent among the four studies that assessed change in intake among residents of the neighbourhood where the new retailer opened for business. For example, one study of 615 residents found essentially no change in fruit and vegetable consumption six to seven months after the opening of a new supermarket in their neighbourhood in Leeds, UK (mean difference=0·04 portions/d)( Reference Wrigley, Warm and Margetts 24 – Reference Gill and Rudkin 27 ). However, two studies found evidence of modest, but not statistically significant, increases in fruit and vegetable intake. The first reported a statistically insignificant 0·42-serving increase in daily intake among a probability sample of sixty-one adults who lived within 0·8 km (0·5) miles of a new fruit and vegetable stand in Austin, Texas, USA two months after it opened( Reference Evans, Jennings and Smiley 36 ). The other study found a 0·29-portion increase among a probability sample of 191 adults who were the main food shoppers for their homes and lived in a Glasgow, UK neighbourhood where a new supermarket was opened at 11-month follow-up (P=0·07)( Reference Cummins, Findlay and Higgins 16 – Reference Cummins, Petticrew and Higgins 18 ). In contrast to these results, a study that included a probability sample of 571 adults living in a neighbourhood in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA where a new supermarket opened, reported a statistically significant 0·27-serving decrease in fruit and vegetable consumption at 6-month follow-up (se=0·08, P<0·001)( Reference Dubowitz, Ghosh-Dastidar and Cohen 22 , Reference Dubowitz, Ncube and Leuschner 23 ).

Two studies reported difference-in-differences comparing change among residents of the neighbourhood where the new retailer opened, relative to change among residents in a comparison neighbourhood. These studies evaluated supermarket openings in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, USA( Reference Dubowitz, Ghosh-Dastidar and Cohen 22 , Reference Dubowitz, Ncube and Leuschner 23 ) and Glasgow, UK( Reference Cummins, Findlay and Higgins 16 – Reference Cummins, Petticrew and Higgins 18 ). In both instances, results were the opposite of what was expected and indicated either greater increases in fruit and vegetable intake among the comparison neighbourhood residents (difference-in-differences=−0·15)( Reference Cummins, Findlay and Higgins 16 – Reference Cummins, Petticrew and Higgins 18 ) or smaller decreases in fruit and vegetable intake among comparison neighbourhood residents (difference-in-differences=−0·14)( Reference Dubowitz, Ghosh-Dastidar and Cohen 22 , Reference Dubowitz, Ncube and Leuschner 23 ).

Discussion

Most studies included in the present review focused on recent openings of healthy food retailers in low-income communities with limited access to healthy foods. The methodological approaches to evaluating these initiatives, including the research designs, sampling approaches, follow-up intervals and outcome measures, varied widely. Although all study designs were limited in their ability to causally attribute any observed change in fruit and vegetable consumption to the opening of the retailer itself, evaluations of supermarket and grocery store openings tended to use more rigorous study designs (e.g. two-group repeated measure or repeated cross-sectional designs with larger representative samples), while evaluations of farmers’ markets, fruit and vegetable stands, and mobile markets tended to use weaker designs (e.g. post-test only designs with smaller convenience samples).

Across study types, results suggest that the dietary impact of the new retailer may be greatest among adults who choose to shop there. For example, three out of four repeated measures studies of shoppers at the new retailer found modest increases in fruit and vegetable consumption, ranging from 0·23 to 0·54 daily servings at 6–12 months follow-up( Reference Wrigley, Warm and Margetts 24 – Reference Gill and Rudkin 27 , Reference Freedman, Choi and Hurley 32 , Reference Abusabha, Namjoshi and Klein 37 ). Although most of these effect sizes did not reach statistical significance, two reported small sample sizes, calling into question whether they were powered to detect dietary change of this magnitude. These effect sizes are similar in magnitude to those reported by a systematic review of behavioural interventions to increase fruit and vegetable intake( Reference Ammerman, Lindquist and Lohr 39 ), and prior research has documented that even small increases in fruit and vegetable intake may be related to reductions in energy density( Reference Williams, Roe and Rolls 40 ). Additionally, results from all three post-test only designs that surveyed shoppers at the new retailer found that relatively high proportions of shoppers reported they were eating more fruits and vegetables since starting to shop there (55–98 %)( Reference Ruelas, Iverson and Kiekel 33 – Reference Woodruff, Coleman and Hermstad 35 ).

The impact of the opening of a new retailer on fruit and vegetable consumption among the broader community of residents of the neighbourhood where the retailer opened was less clear. Studies that used either repeated measures or repeated cross-sectional designs found no evidence of change( Reference Wrigley, Warm and Margetts 24 – Reference Gill and Rudkin 27 , Reference Sadler, Gilliland and Arku 29 , Reference Sadler, Gilliland and Arku 30 ), modest increases( Reference Cummins, Findlay and Higgins 16 – Reference Cummins, Petticrew and Higgins 18 , Reference Elbel, Mijanovich and Kiszko 20 , Reference Elbel, Moran and Dixon 21 , Reference Wang, MacLeod and Steadman 28 , Reference Evans, Jennings and Smiley 36 ) or decreases( Reference Elbel, Mijanovich and Kiszko 20 – Reference Dubowitz, Ncube and Leuschner 23 ) in fruit and vegetable consumption. The variability in results may be explained in part by the heterogeneity in methodological approaches used, including eligibility criteria and methods used to sample intervention neighbourhood residents. Those that also sampled from a comparison neighbourhood were unable to detect a significant difference in mean change in fruit and vegetable consumption between the two groups.

We are limited in our ability to comment on differential dietary impact by retailer type due to the methodological heterogeneity among studies included in the present review. However, evaluations of one category of retailer – supermarkets – tended to have the most methodological consistency, with four out of five studies employing a repeated measures design. These studies found mixed results regarding the impact of the new retailer on fruit and vegetable consumption among shoppers( Reference Dubowitz, Ghosh-Dastidar and Cohen 22 – Reference Gill and Rudkin 27 ), residents of the intervention community( Reference Cummins, Findlay and Higgins 16 – Reference Cummins, Petticrew and Higgins 18 , Reference Dubowitz, Ghosh-Dastidar and Cohen 22 – Reference Gill and Rudkin 27 ), and differences between residents of intervention and comparison communities( Reference Cummins, Findlay and Higgins 16 – Reference Cummins, Petticrew and Higgins 18 , Reference Dubowitz, Ghosh-Dastidar and Cohen 22 , Reference Dubowitz, Ncube and Leuschner 23 ). Although previous reviews have documented systematic disparities in access to supermarkets among many neighbourhoods throughout the USA( Reference Larson, Story and Nelson 5 ), research regarding the causal links between access to supermarkets and improved dietary intake is inconclusive( Reference Caspi, Sorensen and Subramanian 6 ). In the light of the large-scale initiatives focused on policy, systems and environmental changes to improve community retail food environments, many of which focus on introducing supermarkets into low-income communities, more rigorous research with greater methodological consistency is needed regarding the impact of supermarkets on dietary behaviour( 12 – 15 , Reference Bunnell, O’Neil and Soler 41 ).

A strength of the present review is that it is the first to our knowledge to summarize the state of scientific knowledge regarding the potential dietary impact of opening new retailers of healthy foods within a community. Limitations of the review include potential publication bias and incomplete retrieval of relevant articles from the keyword search strategy. Additionally, most studies evaluated the dietary impact of the opening of new retailers within low-income neighbourhoods with limited access to healthy foods in the USA. The extent to which these findings would generalize to other geographic contexts (e.g. developing countries, non-Western contexts, etc.) is unknown. Additionally, the review focused exclusively on the impact of these retailers on fruit and vegetable intake among adults. The impact on fruit and vegetable intake among children or on other outcomes relevant to dietary behaviour or chronic disease prevention remains unknown. Many articles that were considered for( Reference Larsen and Gilliland 42 , Reference Lucan, Maroko and Shanker 43 ) or included in the present review( Reference Elbel, Mijanovich and Kiszko 20 – Reference Dubowitz, Ncube and Leuschner 23 ), or have been published since( Reference Chrisinger 44 – Reference Zhang, Laraia and Mujahid 46 ), assessed other outcomes of interest, including area-level access to healthy foods, change in other dietary behaviours (e.g. change in total energy intake, dietary quality, consumption of specific food groups) or BMI. These may be outcomes of potential interest for future reviews.

Results from the present review suggest that opening a new retailer of healthy foods in limited-access communities may be an appropriate strategy to improve short-term fruit and vegetable intake among adults who choose to shop there, although more research is needed to confirm these findings and to understand the potential impact of this approach on the broader community and/or over longer periods of time. Interventions that focus on other structural interventions, such as improving the in-store environments of existing retailers, may be a more appropriate strategy for improving population-level dietary behaviour( Reference Escaron, Meinen and Nitzke 47 , Reference Liberato, Bailie and Brimblecombe 48 ). Limitations of this body of research include a reliance on pre-experimental or quasi-experimental designs with limited ability to establish causality, potentially underpowered studies reliant on small sample sizes, and the use of a range of outcome measures and follow-up intervals that prevents meta-analytic synthesis of results. Recommendations for future research include designing adequately powered studies that are methodologically aligned with those of previous work, to facilitate comparisons and summary of these initiatives and strengthen the evidence base regarding this potential dietary impact of this approach to improving community food environments.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: The authors acknowledge with gratitude the contributions of Michael Goodman, MD, MPH for his assistance with developing the protocol for this review. The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Financial support: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors. Conflict of interest: None. Authorship: R.C.W. designed the study, performed the study search, abstracted and analysed the data, and prepared the manuscript. I.G.R. abstracted the data and assisted with the preparation of the manuscript. D.M.H., J.A.G., M.K., R.H. and M.C.K. provided oversight of the project and assisted with the preparation of the manuscript. Ethics of human subject participation: Not applicable.