Socio-economic status (SES) is a complex issue characterized by income, education, occupation, marital status and residence status(Reference Metcalf, Scragg and Davis1–Reference Dastgiri, Mahdavi, TuTunchi and Faramarzi3). Although a positive energy balance over a prolonged period is essential for the development of obesity, it is crucial to understand how individual and socio-economic factors may lead to an energy imbalance. SES has been identified as an important factor associated with obesity, particularly in women, because SES influences an individual’s access to resources, knowledge of nutrition and physical activity(Reference Sobal4).

Many studies have documented the higher rates of obesity and overweight among low-SES groups(Reference Mokdad, Serdula, Dietz, Bowman, Marks and Koplan5, Reference Sobal and Stunkard6). The relationship between SES and obesity may vary in industrialized and developing countries(Reference Wang, Monteiro and Popkin7, Reference Popkin, Conde, Hou and Monteiro8). However, other factors, such as parity in women, have been positively associated with weight gain(Reference Wolf, Sobal, Olson, Frongillo and Williamson9–Reference Kim, Stein and Martorell11).

The Islamic Republic of Iran has undergone increasing changes in the prevalence of obesity in recent decades(Reference Azizi, Allahverdian, Mirmiran, Rahmani and Mohammadi12–Reference Azadbakht, Mirmiran, Shiva and Azizi14). The prevalence is reported to be 22–40 % in urban regions and 16–26 % in rural regions of Tehran (Iran’s capital city)(Reference Rashidi, Mohammadpour-Ahranjani, Vafa and Karandish15). One of the provinces in south-east Iran is Sistan and Baluchestan. In the past, as a result of tradition, some men in this region did not like outside employment and education for their wives. Today, this attitude has changed because of improving social thoughts. Also, higher education is now provided by many governmental and private universities and colleges. Therefore, the number of women who enter into higher education is increasing. This has caused educated women to pay more attention to their body shape than before. Moreover, the average number of children born to Sistan and Baluchestan women is still higher than in other regions of Iran(Reference Jamshidbygi16). In this regard, the aim of the present study was to determine the effects of educational level, parity, physical activity and marital status on BMI, waist:hip ratio (WHR) and waist circumference (WC) in a group of Iranian women. The present findings may be applied to target future interventions and research.

Methods

Study subjects

The present study considers cross-sectional data from Sistan and Baluchestan Province in Iran collected between August 2004 and September 2006. This province is located in south-east Iran and contains eight cities. Women who attended two health clinics in two locations in Zahedan were selected. These centres have subjects referred from different parts of Sistan and Baluchestan Province with low, middle and high socio-economic groups. The selected clinics belonged to the public sector, so the samples could be representative of women in this province. The subjects were 888 women all of whom were visited by a single nutritionist. Data collected for each subject included age, weight, height, waist and hip circumferences, marital status, level of education, reproductive history and physical activity. The subjects gave verbal consent for participation in this study.

Anthropometric measurements

BMI was calculated as weight in kilograms divided by the square of height in metres. Waist and hip circumferences were measured during the clinical visit with the subject standing relaxed and in underclothes only. WC was measured at the horizontal point between the costal margin and iliac crest that yielded the minimum measurement. Hip circumference was measured at the horizontal level around the buttocks that yielded the maximum measurement. Then WHR was calculated as the waist circumference divided by the hip circumference. All measurements were done by a trained staff and the instruments were calibrated regularly during the work.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

All participants were originally from different parts of Sistan and Baluchestan Province and had lived there for at least 5 years previously. All subjects were more than 20 years old. The subjects had no metabolic illness, as judged by blood and urine analyses, and none were on a diet or medication. Pregnant women and those who were divorced, separated or widowed were excluded from the study. Based on WHO standards for BMI (underweight, BMI < 18·5 kg/m2; normal weight, BMI = 18·5–24·9 kg/m2; overweight, BMI = 25·0–29·9 kg/m2; obese, BMI ≥ 30·0 kg/m2)(17), women with BMI between 25·0 and 39·9 kg/m2 were included in the study. Also, Pakistani and Afghan immigrant women were excluded from the study (this province is located at the border with Pakistan and Afghanistan).

Variables

Most commonly used variables to measure SES are education, income and occupational status((Reference Metcalf, Scragg and Davis1, Reference Yu, Nissinen, Vartiainen, Hu, Tian and Guo2). Of course, each of these parameters has its own strengths and limitations. Some researchers have used educational level as an indication of SES(Reference Yu, Nissinen, Vartiainen, Song, Guo and Tian18–Reference Schröder, Rohlfs, Schmelz and Marrugat20). In the current study we used education level for the following reasons: (i) education is less affected by a subject’s body weight, whereas her income might be affected; (ii) education is more comparable across time than income or occupation; and (iii) some subjects did not indicate their actual income.

On the basis of education, subjects were classified into three categories: illiterate or low literacy (no education or education completed at <8 years of schooling), intermediary and high school (education completed at between 8 and 12 years of schooling or subsequent non-university studies), and university graduates.

Physical exercise was defined as exercising for at least 20 min and outside professional activity (never, less than once a week, at least once a week). Parity was defined as the number of live births and stillbirths of each woman. Marital status comprised two groups: living single and married.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS/PC) statistical software package version 13 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The results are presented as mean with standard deviation or proportion. Analyses of covariance were used to determine the relationship of BMI, WHR, WC and parity with educational level, controlling for age. We conducted multiple linear regression analyses and examined the relationship between BMI, WHR and WC as dependent variables and age, education and parity as independent variables. Logistic regression analyses were used to find the associations between obesity as binary dependent variable and educational level, parity, marital status and physical activity as independent variables. OR and 95 % CI were also estimated, and P < 0·05 was considered to indicate significance.

Results

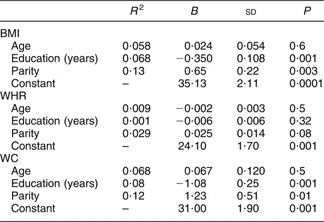

The mean age, BMI, WHR, WC, education level and parity of the participants were 33·2 (sd 9·6) years, 33·5 (sd 5·8) kg/m2, 0·98 (sd 2·20), 101·2 (sd 14·6) cm, 11·3 (sd 4·0) years and 2·8 (sd 2·1), respectively. Of the women, 750 (84·5 %) and 138 (15·5 %) were married and single, respectively (Table 1). In the present study, most subjects (85 %) reported no physical activity, 13 % stated it was less than once a week and 2 % at least once a week. After controlling for age, comparison of measured variables revealed a significant inverse relationship of education level with BMI, WC and parity. There was no significant correlation between educational level and WHR. Therefore women with higher education level had lower BMI, WC and parity (Table 2). Multiple linear regression analyses were conducted separately with BMI, WHR and WC as dependent variables and age, level of education and parity as independent variables. We found a significant negative association of BMI and WC with education level and a significant positive association of BMI and WC with parity. There was no meaningful relationship between WHR and the mentioned variables (Table 3).

Table 1 Sociodemographic characteristics and anthropometric measures of participants: Iranian women, Sistan and Baluchestan Province (n 888)

WHR, waist:hip ratio; WC, waist circumference.

Table 2 Comparison of measured variables in three levels of education controlling for age: Iranian women, Sistan and Baluchestan Province

WHR, waist:hip ratio; WC, waist circumference.

*Comparison between Group 1 and Group 2.

†Comparison between Group 1 and Group 3.

‡Comparison between Group 2 and Group 3.

Table 3 Results of multiple linear regression models (BMI, WHR and WC as dependent variables and age, education and parity as independent variables): Iranian women, Sistan and Baluchestan Province

WHR, waist:hip ratio; WC, waist circumference.

Finally, logistic regression model analyses between BMI and the other variables were performed. The data are presented in Table 4.

Table 4 Results of logistic regression models (dependent variable is obesity: BMI < 30 kg/m2 = 0, BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2 = 1): Iranian women, Sistan and Baluchestan Province

WHR, waist:ratio; WC, waist circumference.

Discussion

The primary objective of the present study was to examine the relationships between SES and BMI, WHR and WC in a group of Iranian women living in Sistan and Baluchestan Province. Our findings suggest that social-economic factors play an important role in associations with obesity. We conclude that educational level, marital status and parity have significant associations with BMI and WC in Iranian women.

Much of the trend towards increased body size among women in Sistan and Baluchestan Province has been attributed to the processes of economic modernization and socio-economic change. Some studies have shown that environmental factors can affect people’s energy intake and expenditure(Reference Hill, Wyatt, Reed and Peters21). Women could be most significantly affected by the revolution in food preparation because they have the greatest opportunity to take advantage of the technical changes. These facilities will cause more sedentary lifestyles in women(Reference Gates, Brehm, Hutton, Singler and Poeppelman22).

In the present study there was a powerful inverse relationship between level of education and obesity in women. These correlations were highest in illiterate or low literacy women and lowest in ones who were graduates from universities or colleges. The same finding is supported by other studies(Reference Dastgiri, Mahdavi, TuTunchi and Faramarzi3, Reference Moreira and Padrao23), although there are some contrasting data on this issue(Reference Du, Lu, Zhai and Popkin24, Reference Al-Nuaim, Bamgboye, al-Rubeaan and al-Mazrou25). In Iran, women of high educational level have more employment than those with less education, which could explain the increased effect of educational level on obesity. A relationship between BMI and unemployment has also been shown to exist in women(Reference Sarlio-Lähteenkorva and Lahelma26). However, the greater frequency of perceived overweight in women with high educational level could lead them to go on weight-reducing diets or take other measures to lose weight in larger proportions than women with an elementary level of education(Reference Levy and Heaton27, Reference Serdula, Collins, Willianson, Anda, Pamuk and Byers28). It should also be noted that more highly qualified women have greater access to weight-reducing treatments as these carry a certain cost. Since our analysis is based on cross-sectional data, further studies are needed to clarify it.

We also observed remarkable differences in parity and obesity among women in the present study. Reproduction is considered an important determinant of weight gain during a woman’s life. This factor has been related with the social gradient in obesity in women because weight gained during pregnancy is not lost completely at term(Reference Noppa and Bengtsson29). Some research shows that women with lower age and social level have more children(Reference Wamala, Wolk and Orth-Gomér30). This fact may be important in explaining the social differences in obesity among women. BMI has been shown to increase with the number of pregnancies(Reference Rissanen, Heliovaara, Knekt, Reunanen and Aromaa31). Our data revealed similar findings.

Moreover, physical activity is reported as a determinant of body weight in some studies(Reference Croff, Strogatz, James, Keenan, Ammerman, Mararcher and Haines32). Regular physical activity helps reduce the risk of heart disease(Reference Fransson, de Faire, Ahlbom, Reuterwall, Hallqvist and Alfredsson33, Reference Corrado, Migliore, Basso and Thiene34), control mild hypertension(Reference Hayashi, Ohshige and Tochikubo35), modify blood lipids(Reference Mbalilaki, Hellenius, Masesa, Hostmark, Sundquist and Stromme36, Reference Adamu, Sani and Abdu37) and protect against the onset of osteoporosis in women(Reference Jamsa, Vainionpaa, Korpelainen, Vihriala and Leppaluoto38). One of the most striking characteristics of our study was the low level of physical activity reported by most of the participants. In this region of Iran, women do not have much access to sporting activities, and physical activity is restricted to housework. Traditionally, some of them consider obesity to be a sign of good health and beauty, an attitude that may contribute to the current situation.

Marital status represents another social dimension. The present study showed that married women gain more weight than single women. In Iran, marriage usually changes women’s attitude to life. They prefer to spend more time with their family and less think about their own body shape. However, intensive investigation is needed in Iran to conclude better results.

Conclusions

The present study revealed that lack of exercise, multiple pregnancies, marital status and education are some of the possible explanations for obesity among women residing in Sistan and Baluchestan Province. Obesity prevention should be a relevant topic on the public health agenda in developing countries such as Iran. Without developing effective strategies to modify the current situation, it is likely that the obesity epidemic will continue in the future.

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of interest: There is no conflict of interest.

Source of funding: The Medical Faculty of Zahedan University of Medical Sciences funded the research.

Author contributions: M.S. was project manager and designer of the research; T.S. collaborated in writing the paper and collecting data; H.A. collaborated in analysing the data.

Acknowledgement: Our thanks go to all who participated actively in this project. We are thankful to the Research Center for Children and Adolescents Health for their invaluable help.