Nutrition labelling on food packages has been voluntarily implemented by food companies since the beginning of the 20th century. By the end of the 20th century, both governments and non-governmental organizations began to implement different front-of-package (FOP) nutrition labelling systems. FOP nutrition labels encompass a specific element of nutrition labelling postulated to allow for quick decision making about the nutritional content or relative healthfulness of a product provided through its simple, easily viewable and interpretable format( Reference Feunekes, Gortemaker and Willems 1 , Reference Pomeranz 2 ). The policy objectives of FOP nutrition labelling are typically twofold: (i) to provide additional information to consumers to inform healthier food choices; and (ii) to encourage the industry to reformulate products towards healthier options. Recent reviews have summarized the implementation of nutrition labelling policies in general( Reference Hieke and Taylor 3 , Reference Kasapila and Shaarani 4 ). However, there has been an exponential rise in both government and private-sector FOP nutrition labelling policy that deserves specific attention( Reference Schermel, Emrich and Arcand 5 , 6 ).

While it has been argued that FOP nutrition labelling is a marketing, rather than a public health strategy( Reference Brownell and Koplan 7 ), the purpose of this editorial is to provide an update on the global policy environment regarding government-endorsed FOP nutrition labelling and to examine real-world evidence of policy implementation.

Notable global policy action

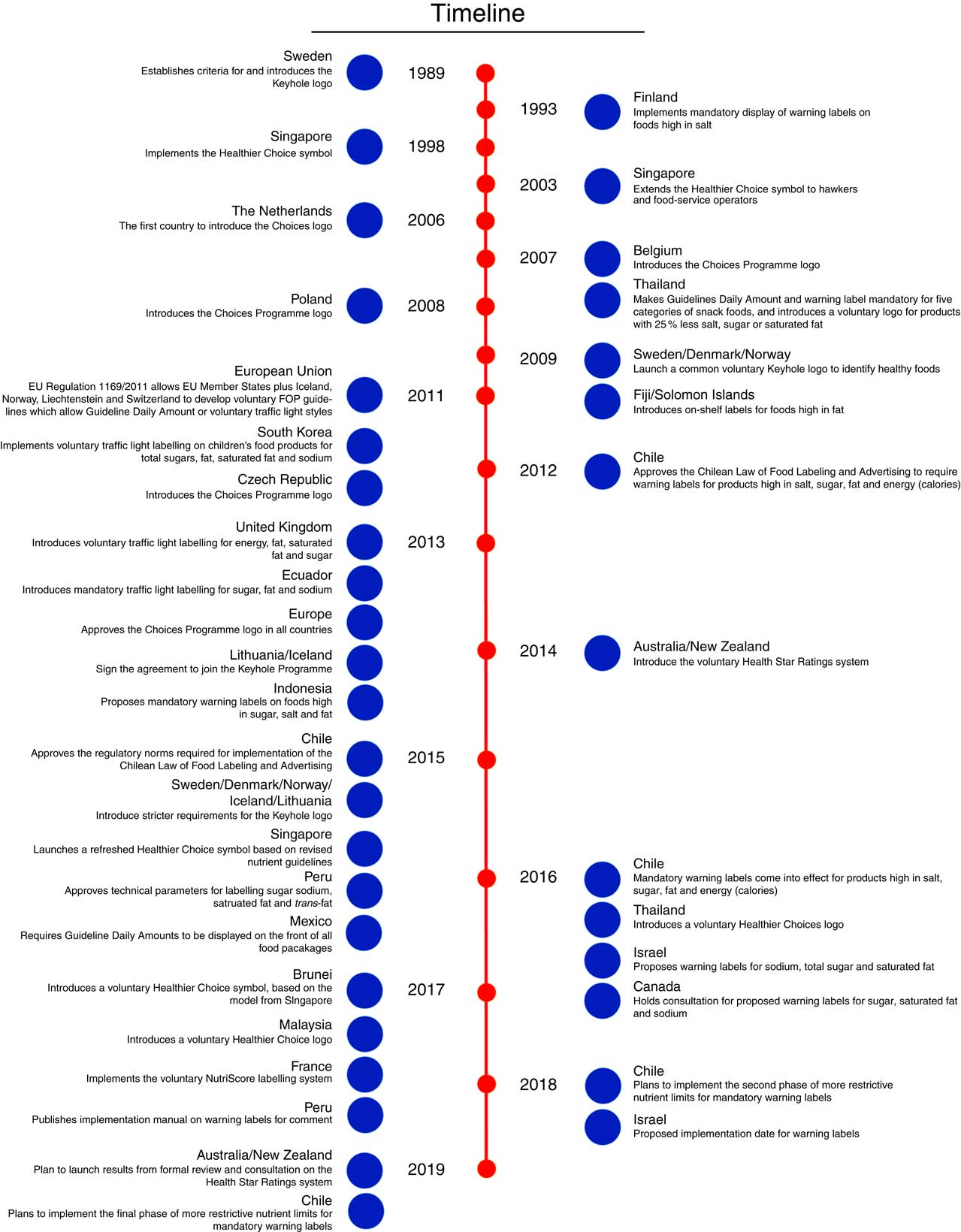

With the start of the 21st century, concomitant with the emerging global obesity epidemic and the greater abundance of ultra-processed foods in the marketplace( 8 , Reference Moodie, Stuckler and Monteiro 9 ), the number of both public and private FOP nutrition labelling initiatives has increased steadily( 10 ) (see Fig. 1 for a timeline of FOP policy implementation globally).

Fig. 1 (colour online) Timeline of front-of-package (FOP) nutrition labelling globally (adapted from the NOURISHING framework( 6 ) and other sources)

The WHO first proposed FOP nutrition labelling as a policy measure to improve diet and health in 2004( 11 ). Thereafter, the WHO has repeatedly sought to promote FOP nutrition labelling as part of a comprehensive policy response to the global epidemic of obesity and diet-related non-communicable diseases, including through the Global Action Plan for the Prevention and Control of Noncommunicable Diseases, the Commission on Ending Childhood Obesity, and specific FOP nutrition labelling workshops( 12 – 15 ). In 2012, the Institute of Medicine (now the National Academy of Medicine) published a comprehensive review on FOP nutrition labelling that issued the following recommendations regarding any FOP nutrition labelling evaluation scheme: (i) allow only four items (energy (calories), saturated fat, trans-fat, sodium, sugars); and (ii) keep the format simple, easy to interpret, integrated with other nutrition information and supported by communication( 16 ). In contrast, the WHO’s recommendations regarding FOP nutrition labelling are not specific regarding format, content and criteria of such labelling. Thus, unlike for back-of-package nutrition information panels and ingredients lists, there is currently no explicit international agreement for national mandatory FOP nutrition labelling in the current standards of the Codex Alimentarius Commission( 17 ).

The development of such a standard, however, is now under formal consideration by the Codex Committee on Food Labelling( 18 ). This is important as the World Trade Organization considers Codex standards when resolving trade disputes between states. Nutrition labelling requirements have been cited as ‘technical barriers’ to the trade of packaged food products across borders. For example, specific trade concerns have been raised at the World Trade Organization’s Technical Barriers to Trade Committee regarding FOP nutrition labelling schemes in Thailand, Chile, Indonesia, Peru and Ecuador( Reference Thow, Jones and Hawkes 19 ). These concerns are related to the consistency of proposed policies with international standards (i.e. their deviation from Codex Alimentarius guidelines) and the justification of such policies, supported by scientific evidence of effectiveness of the specific systems proposed compared with alternative approaches that aim to improve population nutrition with less impact on trade( Reference Thow, Jones and Hawkes 19 ).

Variation in front-of-package nutrition labelling schemes

Worldwide, FOP nutrition labelling has been implemented through government policies in a myriad of ways utilizing different terminology (see Table 1 for a list of commonly used terms in the FOP literature). A summary of the various FOP nutrition labelling schemes introduced globally can be found in Table 2.

Table 1 Terms used for various types of government-endorsed front-of-package nutrition labelling schemes

Table 2 Characteristics of the front-of-package (FOP) nutrition labeling schemes introduced globally

FOP nutrition labelling schemes vary in presentation (e.g. shape, colour, size), type of public health nutrition message (proscriptive, prescriptive or both) and nutrient focus (e.g. focus on ‘critical nutrients’ or inclusion of both positive and negative nutrients). To date, the most common ‘critical nutrients’ that have been included in FOP nutrition labelling schemes are sodium, fats (saturated, trans) and total sugars, as recommended in the Institute of Medicine report( 16 ). Some, but not all, of the FOP nutrition labelling schemes also include certain nutrient-rich components, such as fibre, whole grains, protein and/or fruits and vegetables. Below is provided a summary of various government-led FOP nutrition labelling schemes that have been implemented, divided by type, and how they vary.

Health logos

The first FOP nutrition labelling systems to be implemented were health logo systems. The Keyhole logo was the first logo system introduced in 1989, mainly in the Nordic European countries (Table 2). The Choices Programme logo is an international industry-led scheme that was later endorsed by some European governments. It was first introduced in the Netherlands in 2006, but received EU-wide approval in 2013. Several Asian countries based the development of their healthier choices logos on the Choices International system( 20 ). Unlike other systems, the Choices Programme includes trans-fatty acids and added sugar within its criteria. In some countries, such as Brunei, manufacturers must supply a food analysis report from an accredited food laboratory to the Choices Programme Committee before they can use the logo on their products. While logos have been widely introduced in a range of countries (Table 2), some research groups, like INFORMAS (International Network for Food and Obesity/non-communicable Diseases Research, Monitoring and Action Support), consider logos to be health claims rather than interpretive FOP nutrition labelling( Reference Rayner, Wood and Lawrence 21 ).

Traffic lights

Traffic light FOP nutrition labelling is named as such because it uses the typical traffic light colours (green, yellow/amber, red) to denote prescriptive and proscriptive nutrient contents, respectively. Traffic light FOP nutrition labelling has been relatively less popular and has been introduced by only three countries (the UK, Ecuador and South Korea), only one of which is mandatory (Ecuador; Table 2). The UK and South Korean FOP nutrition labelling systems include both total and saturated fat, compared with Ecuador that only includes total fat. While voluntary, the limits for total fat are more restrictive in the UK than in Ecuador, while the opposite occurs for total sugars (Table 2). Some early results from Ecuador show reductions in sales of some unhealthy food groups one year after implementation( Reference Díaz, Veliz and Rivas-Mariño 22 ). In South Korea, the traffic light FOP nutrition labelling system in place applies only for specific children’s foods (e.g. snacks)( 6 ).

Summary indicator front-of-package nutrition labelling

The first summary FOP nutrition labelling system that was developed was the Health Star Ratings by Food Standards Australia New Zealand. The Health Star Ratings system was implemented in 2014 in Australia and New Zealand on a voluntary basis, with products receiving from half a star up to 5 stars dependent on healthfulness defined by negative as well as positive components. Although implementation of the system is slow, with only 5 % of the packaged foods in New Zealand carrying Health Star Ratings as of 2016, there are some positive impacts on product reformulation when comparing products with stars and those without stars in the same product categories( Reference Mhurchu, Eyles and Choi 23 ). In 2017, France developed and implemented a similar voluntary system with five categories, using colour coding and letters (from A to E) that are used to summarize the healthfulness of products rather than a star-based system (Table 2)( Reference Julia, Peneau and Buscail 24 ).

Warning labels

Warning labels that denote foods that are high in certain critical nutrients are another type of FOP nutrition labelling system to be introduced into legislative frameworks. Finland was the first country introducing a warning label for excessive sodium content in some food products in the early 1990s( Reference Pietinen, Valsta and Hirvonen 25 , Reference Pietinen, Männistö and Valsta 26 ). In 2016, Chile was the first country to require ‘high in’ symbols for products that exceed limits for three critical nutrients (sodium, saturated fats, total sugars) and total energy (kilocalories). The same Chilean Law of Food Labelling and Advertising includes the prohibition of marketing foods that qualify for these FOP labels to children under 14 years old, as well as their sale on primary school premises( Reference Corvalán, Reyes and Garmendia 27 ). Canada, Israel and Peru are all in the process of developing a similar system( 28 – 30 ). In contrast to Chile, Canada is proposing to set limits per serving rather than per 100 g and does not include energy (Table 2)( 28 ). Additionally, FOP health warnings describing potential negative consequences of consuming categories of food, such as sugar-sweetened beverages, have been proposed in the USA, but have not been successfully implemented to date( Reference Popova 31 ).

Lessons learnt and recommendations for further research

The increased uptake of FOP nutrition labelling interventions implemented by governments shows both increasing political and societal acceptability of FOP nutrition labelling. The action by Codex in formally considering global guidelines for FOP nutrition labelling is also an important step forward. Global momentum is increasing for FOP nutrition labelling that inherently motivates countries to act, such as is the case for taxes on sugar-sweetened beverages( Reference Backholer, Blake and Vandevijvere 32 ). While the rate of policy implementation or consideration is concomitant with the increasing amount of research being conducted in this field, many knowledge gaps remain.

First, while it is well established that interpretive labels are more likely to have an impact on consumer understanding and behaviour than reductive systems alone, less is known about the relative effectiveness or superiority of the various types of interpretive FOP nutrition labelling systems( Reference Hawley, Roberto and Bragg 33 – Reference Cecchini and Warin 36 ). Consumer research on FOP nutrition labelling has largely examined health logos and traffic light symbols and, to a lesser extent, Health Star Ratings( Reference Volkova and Mhurchu 37 , Reference Arrúa, Curutchet and Rey 38 ). Given the recent introduction of ‘high in’ FOP nutrition labelling into the policy sphere, more research is needed to examine this labelling scheme, as most of this research is limited to South American contexts( Reference Volkova and Mhurchu 37 , Reference Arrúa, Machín and Curutchet 39 , Reference Cabrera, Machín and Arrúa 40 ). The various FOP nutrition labelling systems support different policy objectives. Therefore, evidence of the comparative impact of these systems on various outcomes, including consumer behaviour and industry reformulation, is warranted. The impact of FOP nutrition labelling systems on reformulation deserves more attention as early results from New Zealand show some positive impact for the Health Star Ratings( Reference Mhurchu, Eyles and Choi 23 ); however, the volume of evidence of the impact of government-initiated FOP nutrition labelling schemes on food reformulation is scarce( Reference Mhurchu, Eyles and Choi 23 , Reference Wyness, Butriss and Stanner 41 , Reference Mandle, Tugendhaft and Michalow 42 ). There is additional evidence, from voluntary FOP nutrition labelling programmes developed by non-governmental organizations, that FOP nutrition labelling has had positive impacts on the food supply( Reference Vyth, Steenhuis and Roodenburg 43 – Reference Ning, Mainvil and Thomson 45 ). Taken together, as more government-sponsored FOP nutrition labelling systems are implemented there is an evident need for more research on how these systems impact industry behaviour, which may subsequently impact consumer behaviour.

Second, limited literature has examined label characteristics that relate to salience, specifically the necessary size of labels, the colour of labels, or the placement of labels on food packages( Reference Cabrera, Machín and Arrúa 40 , Reference Becker, Bello and Sundar 46 ). Literature from tobacco warning labels has identified these as key characteristics that can influence consumer likelihood of noticing label information and the strength of message portrayed to consumers; this deserves additional attention in the packaged food field( Reference Hammond 47 ). The above characteristics are particularly important to policy makers in helping to establish detailed regulations for FOP nutrition labelling requirements.

Third, as previously mentioned above, the foundational concept of FOP nutrition labelling is the ability of these schemes to communicate information in a simple, understandable format to individuals with low literacy levels who face greater challenges understanding complex, numeric information often on the back of food packages. While the differential effect of FOP nutrition labelling along sociodemographic and literacy lines is starting to be incorporated into the literature( Reference Watson, Kelly and Hector 48 – Reference Kelly, Hughes and Chapman 50 ), there is still a lack of understanding of who benefits from FOP nutrition labelling policies and what these policies will do to existing health inequities. Recently, Backholer and colleagues have come up with a framework for doing so, and this deserves additional attention( Reference Backholer, Beauchamp and Ball 51 ).

Fourth, there is a lack of research that examines FOP nutrition labelling use in real-world settings, with most research being conducted in online environments( Reference Watson, Kelly and Hector 48 ). Online studies can provide insight into the impact of FOP nutrition labelling on consumer understanding and perceived willingness to pay or intent to purchase. Yet, the online setting is limited in its ability to require consumers to factor in issues known to influence purchasing habits significantly, such as the time dedicated to each purchasing decision, brand loyalty and taste preferences. Online research is also limited in its ability to capture how understanding and use of FOP nutrition labelling may change over time, or how supplemental education campaigns (by government, industry or both) may support consumer understanding. The paucity of evidence of the public health impacts, especially regarding the real-world impact on consumer purchases and dietary habits and industry actions, is largely indicative of the short amount of time that has lapsed since the government-sponsored creation and implementation of FOP nutrition labelling. Rigorous quasi-experimental studies with objective data such as sales data, and cross-country comparisons examining the FOP nutrition labelling policies implemented to date, have the potential to fill this evidence gap.

Finally, there are important policy decisions to be made regarding the implementation of voluntary government-endorsed FOP nutrition labelling policies (such as the Health Star Ratings in Australia and New Zealand) v. mandatory policies (such as those implemented in Chile and Ecuador, among others). Voluntary guidelines or schemes do not require labels on all packages, which may bias consumer perceptions towards products with labels that are equally, or potentially less, healthful than products with no labels, as has been demonstrated in previous research( Reference Talati, Pettigrew and Dixon 52 ). In addition, evidence to date suggests that the uptake of voluntary FOP nutrition labelling is slow, as demonstrated in New Zealand where only 5 % of products carry the Health Star Ratings( Reference Mhurchu, Eyles and Choi 23 ). Finally, decisions regarding mandatory or voluntary implementation may also influence the amount of opposition from industry with regard to FOP nutrition labelling policy. Preliminary evidence from Canada and Chile suggests that there is a high level of opposition to mandatory warning label policy( 53 , Reference Velasco 54 ). Similarly, while evidence from the EU suggests that voluntary schemes are more palatable to industry stakeholders and less likely to be lobbied, EU countries currently can only implement voluntary schemes by EU regulation( 55 ).

Conclusion

An increasing variety of FOP nutrition labelling systems have been implemented to date globally with two common goals: (i) to communicate complex information to consumers in an easily understood, standardized format, to guide, inform and shape consumer food choices and behaviours; and (ii) to stimulate industry reformulation. Few FOP nutrition labelling systems are currently mandatory and therefore evidence of the real-life impact of mandatory FOP nutrition labelling systems on consumer behaviour and industry reformulation is limited. The potential impact of FOP nutrition labelling on reducing nutrition inequalities is uncertain and it is therefore important to evaluate the ability of FOP nutrition labelling schemes to effectively communicate information to different target groups. The published studies to date that include voluntary FOP nutrition labelling suggest that the impact of FOP nutrition labelling on industry reformulation may have greater potential to affect all consumers, independent of sociodemographic characteristics, compared with impacts on consumer behaviour that are often influenced by sociodemographic characteristics. As most of the mandatory FOP nutrition labelling schemes have been implemented only over the past 5 years, it is anticipated that more scientific evidence will become available that will further accelerate the uptake of this important policy option on a global scale.