People often distort interpretation of information surrounding them(Reference Coutts, Gruman, Schneider, Gruman and Coutts1). This could waste social resources and reduce quality of life in individuals to offset dissatisfaction with distorted information, and the same is true of the perception of body image(Reference Nayir, Uskun and Yürekli2,Reference Baker, Blanchard and Lobera3) . Many studies have reported mental distress and poor quality of life in obese or underweight people(Reference Pimenta, Bertrand and Mograbi4–Reference Hassan, Joshi and Madhavan6). However, if quality of life is reduced by distorted cognition regarding the body even in those who are not obese or underweight, it could be considered another social harm caused by body image.

Body image refers to how one perceives, feels and thinks about one’s body(Reference Grogan7,Reference Muth and Cash8) . Body image disturbance is defined as the distortion of perception, behaviour or cognition related to physical appearance(Reference Posavac and Posavac9). Body image disturbance is becoming a social problem, particularly in developed societies, including Western countries, and is related to mental health outcomes(Reference Pimenta, Sánchez-Villegas and Bes-Rastrollo10) including depression, eating disorders such as anorexia nervosa or bulimia nervosa, and body dysmorphia(Reference Dunkley and Grilo11–Reference Veale, Kinderman and Riley15). Of course, body image disturbance does not only have a negative effect on weight or health. For example, overweight adolescents were associated with less weight gain in the future if their weight was viewed as normal(Reference Sonneville, Thurston and Milliren16). Body image and its disturbance have multidimensional components including perceptual, cognitive, affective and behavioural factors(Reference Vocks, Legenbauer and Rüddel17).

Various authors have demonstrated the role of gender in body image and suggested that sociocultural pressure on women to achieve an unrealistic body image can be related to dissatisfaction(Reference Bordo18–Reference Thompson, Heinberg and Altabe20) and undesirable health behaviours such as eating disorders(Reference Benveniste, Lecouteur and Hepworth21–Reference Shroff and Thompson24), cosmetic surgery(Reference Davis25–Reference Slevec and Tiggemann27) and smoking(Reference King, Matacin and White28–Reference Croghan, Bronars and Patten30). In contrast, the context of body image-related research involving men differs from that of women, with its short history and a lack of admiration for thin body shapes because of men’s affinity for muscular bodies(Reference Grogan7,Reference Pope, Pope and Phillips31,32) . One study suggested that a gender stereotype of physical attractiveness could be influenced by mental status(Reference Barber33). While self-esteem is an important predictor of body image, the difference in self-esteem between men and women cannot account for the relationships between gender and body image(Reference Jackson, Sullivan and Rostker34,Reference Kearney-Cooke35) . However, despite the large volume of research conducted to examine body image, few studies have explored body image perception in men and women in detail(Reference Brennan, Lalonde and Bain36). While gender differences have been reported in other studies, they did not control for socio-economic status(Reference Crawford and Campbell37,Reference Ziebland, Thorogood and Fuller38) , and the study populations were limited to young adults(Reference Gross, Gary and Browne39).

Complex and multidimensional dynamics operate to form body image, and various factors, such as gender, ethnicity, culture, age and the state of the body and mind, are related to body image(Reference Grogan7,Reference Muth and Cash8,Reference Cash and Smolak40) . While relatively little is known about the relation between marital status and body image disturbance, it was reported that while men’s marital status was unrelated to their perceived weight status, married women were more likely to perceive themselves as overweight than unmarried women(Reference Klos and Sobal41). On the other hand, it was reported that while marital status had no significant effect on weight perception for men, women who had never been married were more likely to perceive themselves as heavier weight than those married and living with a partner(Reference Boo42). Several studies have reported that area of residence is related to body image(Reference Luo, Parish and Laumann43–Reference Petroski, Pelegrini and Glaner45). Women had stronger body image concerns if they were living in coastal areas(Reference Luo, Parish and Laumann43). For adolescents, the prevalence of body image dissatisfaction was high among adolescents from small-sized municipalities(Reference Fidelix, Silva and Pelegrini44). On the other hand, when comparing body image dissatisfaction between rural and urban, both areas were similar: a high prevalence of body image dissatisfaction was observed among adolescents from rural and urban areas(Reference Petroski, Pelegrini and Glaner45).

In the current study, in relation to body image disturbance, we compared body weight misperception between men and women and explored factors related to body weight misperception between genders in the general population. Weight misperception is the over- or underestimation of one’s weight. Unlike most previous studies(Reference Sirirassamee, Phoolsawat and Limkhunthammo46–Reference Shin and Nam51) that compared body weight perception and obesity and categorised them as over-, under- or correct estimation, to measure body weight misperception, the current study subdivided weight misperception levels into five categories by matching them to actual weight levels, because, for example, in the case of overestimation, there is a difference between people of a healthy weight who perceive themselves as overweight and underweight people who perceive themselves as being of a healthy weight.

Methods

Participants

We used data from the Seventh Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES VII, 2016–2018). As data up to 2017 were refined and available at the time of the study, we analysed 2016/2017 data from the KNHANES VII. These surveys have been conducted periodically by the Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention since 1998 to assess health and nutritional status in the general Korean population. The KNHANES consists of four parts: the Health Interview Survey, Health Behavior Survey, Health Examination Survey and Nutrition Survey. The data for each year of the KNHANES VII were collected via a cross-sectional and nationally representative survey using a multistage, stratified sampling design. After providing informed consent, participants completed an extensive interview and underwent assessment in a mobile examination centre. The health interview and health examination are performed by trained medical staff and interviewers. The nutrition survey is conducted at participants’ homes 1 week after the health interview. The KNHANES VII was approved by the institutional review board at the Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Detailed information about the KNHANES is provided elsewhere(Reference Kweon, Kim and Jang52). The KNHANES VII data for 2016/2017 include information regarding 16 277 individuals (8832 families from 384 sectors based on region and housing). After the exclusion of those aged ≤18 years, 12 900 participants were included in the study.

Assessment

Objective weight status was determined using BMI (underweight: <18·5 kg/m2, healthy weight: 18·5–24·9 kg/m2 and overweight: ≥25 kg/m2). The weight was measured using a digital weight scale (measurement interval: 0·1 kg) according to the Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s examination survey guidelines. Those under 10 years of age should be zeroed in with a 0·5 kg correction weight, and those over 10 years of age should be worn with a disposable examination gown before zeroing in. With personal belongings (glass, mobile phone, accessory, locker key, etc.) are not worn, standing barefoot on the tread plate, keeping the eyes forward and the arms down naturally on both sides, and while breathing in, the measurement is conducted up to one decimal place (0·1 kg).

To measure self-perceived body image in terms of body weight, participants’ perceptions of their weight were assessed via the following items: ‘How would you describe your weight?’ with possible responses of ‘very underweight’, ‘a little underweight’, ‘healthy weight’, ‘a little overweight’ and ‘very overweight’. To compare objective and self-perceived weight status, responses of ‘very underweight’ and ‘a little underweight’ were categorised as ‘underweight’, and ‘a little overweight’ and ‘very overweight’ were categorised as ‘overweight’. Participants were placed into five groups according to body image perception and objective weight status as follows: perceiving oneself as being of a healthy weight despite being underweight, perceiving oneself as being of a healthy weight despite being overweight, self-perception concordant with objective weight status, perceiving oneself as underweight despite being of a healthy weight and perceiving oneself as overweight despite being of a healthy weight.

Household income and educational level were classified into four categories. Marital status was classified as married, widowed, divorced or unmarried. Subjective health status was assessed using the item, ‘How do you usually think about your health status?’ Participants chose one of five categories: very unhealthy, unhealthy, medium, healthy and very healthy. In the data analysis, responses of very healthy and healthy were categorised as ‘good health’, and very unhealthy and unhealthy were categorised as ‘poor health’. Therefore, we used three categories: good health, medium and poor health. Stress perception was assessed using the item, ‘How much stress do you experience in your daily life?’ The presence of depression was assessed using the item, ‘Have you ever been diagnosed with depression by a doctor?’ Participants were asked questions regarding their physical activity levels during a normal week. To identify moderate physical activity, participants were asked the following: ‘Do you usually engage in moderate physical activity for at least 10 minutes (e.g., fast walking, jogging, weight training, golf, dance sports, pilates, or any other activity that causes a slight increase in breathing or heart rate)?’

Statistical methods

Pearson’s χ 2 test was performed to identify significant associations between various variables and body weight misperception. Multinomial logistic regression was performed to determine which factors were independently associated with the body weight misperception. Variables with a significance level of P < 0·1 in the bivariate analysis were entered into the model. The variables put into the final model of multinomial logistic regression for men include age, marital status, household income, education, residence, subjective health perception, stress perception and physical activity. In the case of women, depression, a variable that was not significant in univariate analysis in men, was added to the model in addition to the above variables.

The analysis was performed using SPSS version 16(53).

Results

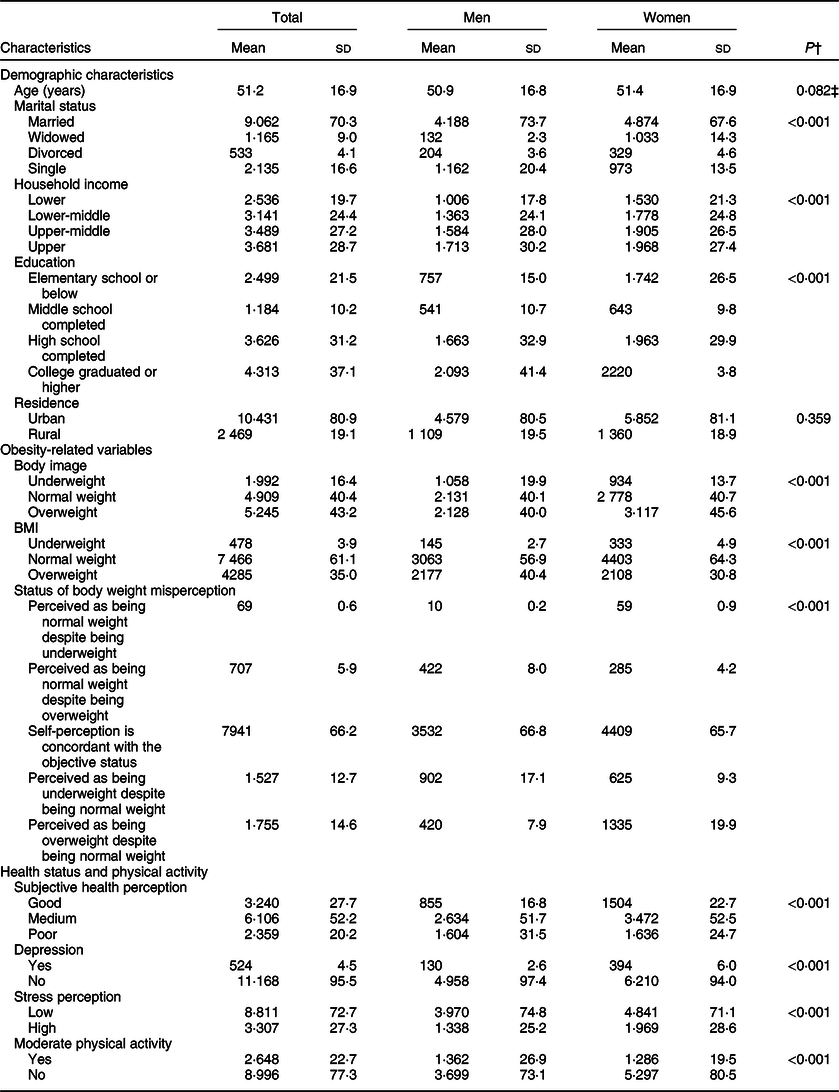

Table 1 shows the participants’ socio-demographic characteristics. In total, 16·4, 40·4 and 43·2 % of participants perceived themselves as underweight, a healthy weight and overweight, respectively. In contrast, based on BMI measurement, 3·9, 61·1, 35·0 % of participants were underweight, a healthy weight, and overweight, respectively. When we grouped the participants according to agreement between body image perception and objective weight status, the proportions of participants in the groups were as follows: perceiving oneself as being of a healthy weight despite being underweight (0·6 %), perceiving oneself as being of a healthy weight despite being overweight (5·9 %), self-perception concordant with objective weight status (66·2 %), perceiving oneself as being underweight despite being of a healthy weight (12·7 %) and perceiving oneself as being overweight despite being of a healthy weight (14·6 %). In addition, 20·2 % of participants perceived their health status as poor, and 27·3 % believed that they experienced high levels of stress. Moreover, 4·5 % of participants had been diagnosed with depression, and 22·7 % engaged in regular physical activity. Comparisons between men and women showed higher rates of bereavement, lower household income and lower levels of education for women than men. Both the proportion of those who thought they were underweight and the proportion of those who were actually overweight were higher in men. The proportions of men who perceived themselves as underweight despite being of a healthy weight were higher relative to those of women. In contrast, the proportions of women who perceived themselves as overweight despite being of a healthy weight were higher relative to those of men. Subjective health status was slightly better in women, but depression and stress perception rates were slightly higher in women. The percentage of people practicing regular physical activity was slightly higher in men.

Table 1 Characteristics of the sample*

* Data are given as numbers (valid percent), unless otherwise specified.

† P values were determined using χ 2 tests.

‡ P value was determined using Student’s t test.

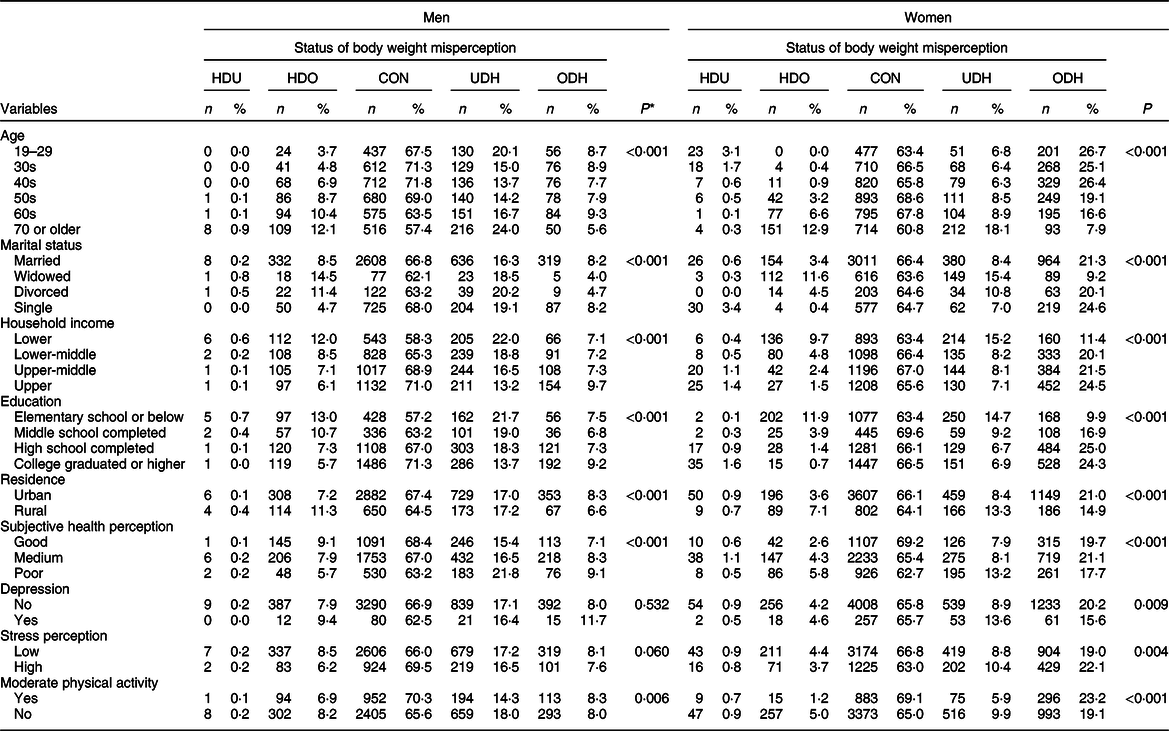

Table 2 shows the results of the univariate analysis of associations between various factors and body weight misperception according to gender. Regarding the association between age and body image, the proportion of men or women who perceived themselves as being of a healthy weight despite being overweight increased as their age increased. The proportion of women who perceived themselves as overweight despite being of a healthy weight decreased as their age increased.

Table 2 Association between various factors and body weight misperception by gender

HDU, perceiving oneself as being of a healthy weight despite being underweight; HDO, perceiving oneself as being of a healthy weight despite being overweight; CON, self-perception concordant with objective weight status; UDH, perceiving oneself as underweight despite being of a healthy weight; ODH, perceiving oneself as overweight despite being of a healthy weight.

* P values were determined using χ 2 tests.

Concerning the association between marital status and body image, the proportion of men or women who perceived themselves as being of a healthy weight despite being overweight was highest among those who were widowed.

Regarding the association between household income and body image, the proportions of men whose self-perception was concordant with their objective weight status and perceived themselves as overweight despite being of a healthy weight increased as their household income increased.

Concerning the association between education and body image, the proportions of men or women who perceived themselves as being of a healthy weight despite being overweight and as being underweight despite being of a healthy weight decreased as their educational levels increased.

Regarding the association between residence and body image, the proportion of men or women living in rural areas who perceived themselves as being of a healthy weight despite being overweight was higher relative to that of men living in urban areas. The proportion of women living in urban areas who perceived themselves as overweight despite being of a healthy weight was higher relative to that of women living in rural areas.

Regarding the association between subjective health perception and body image, the proportions of men or women whose self-perception was concordant with their objective weight status increased as their subjective health levels increased. In contrast, the proportion of men or women who perceived themselves as underweight despite being of a healthy weight decreased as their subjective health levels increased.

Concerning the association between depression and body image, the proportion of women who perceived themselves as underweight despite being of a healthy weight was higher in those with depression, relative to that of women without depression. The proportion of women who perceived themselves as overweight despite being of a healthy weight was higher in those without depression, relative to that of women with depression.

Regarding the association between physical activity and body image, the proportion of men or women who engaged in regular physical activity and whose self-perception was concordant with their objective weight status was higher relative to that of those who did not engage in regular physical activity.

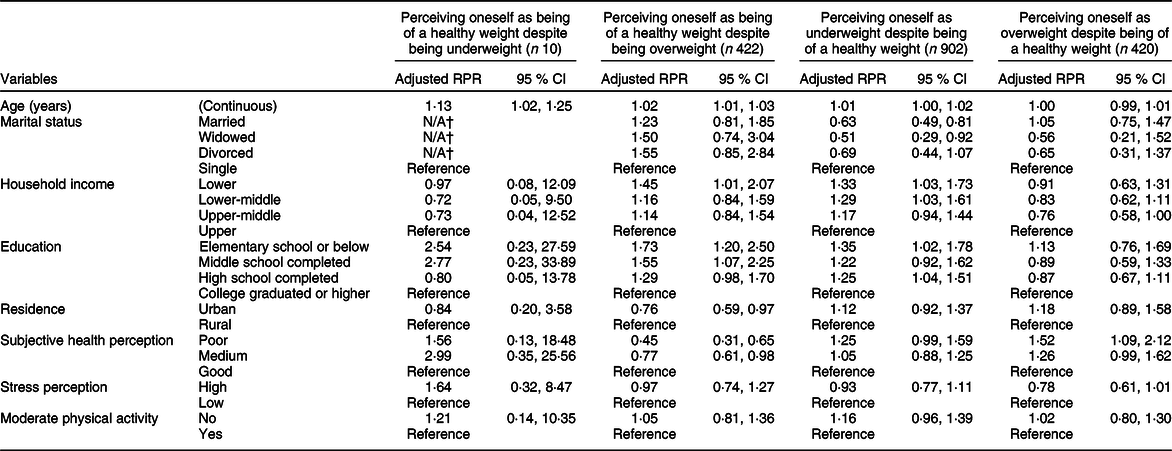

Table 3 shows the results of the multinomial logistic regression analysis of factors associated with body weight misperception in men. Every 1-year increase in age increased the relative prevalence ratios (RPR) of participants perceiving themselves as being of a healthy weight despite being underweight by 1·13 (95 % CI 1·02, 1·25).

Table 3 Multinomial logistic regression results examining factors associated with body weight misperception in men*

RPR, relative prevalence ratios; N/A, not available.

* ‘Self-perception is concordant with the objective status’ is the reference category.

† Due to the reason that the number of single men in the category ‘Perceived as being normal weight despite being underweight’ is zero.

Each 1-year increase in age increased the RPR of participants perceiving themselves as being of a healthy weight despite being overweight by 1·02 (95 % CI 1·01, 1·03). Men whose household income levels were low were 1·45 times more likely to perceive themselves as being of a healthy weight despite being overweight relative to those whose household income levels were high (95 % CI 1·01, 2·07). A lower educational level was a predictive factor for participants perceiving themselves as being of a healthy weight despite being overweight (1·73 times more likely for elementary school or below, 1·55 times more likely for middle school). Men who lived in urban areas (RPR = 0·76, 95 % CI 0·59, 0·97) and had poor (RPR =0·45, 95 % CI 0·31, 0·65) or medium (RPR = 0·77, 95 % CI 0·61, 0·98) perceived subjective health were less likely to perceive themselves as being of a healthy weight despite being overweight.

Men who were married (RPR = 0·63, 95 % CI 0·49, 0·81) or widowed (RPR = 0·51, 95 % CI 0·29, 0·92) were least likely to perceive themselves as underweight despite being of a healthy weight. Men whose household income levels were low (RPR = 1·33, 95 % CI 1·03, 1·73) or in the lower-middle range (RPR = 1·29, 95 % CI 1·03, 1·61) and whose educational level was low (elementary school or below (RPR = 1·35, 95 % CI 1·02, 1·78), high school (RPR = 1·25, 95 % CI 1·04, 1·51)) were most likely to perceive themselves as underweight despite being of a healthy weight. Men whose perceived subjective health was poor were most likely to perceive themselves as overweight despite being of a healthy weight.

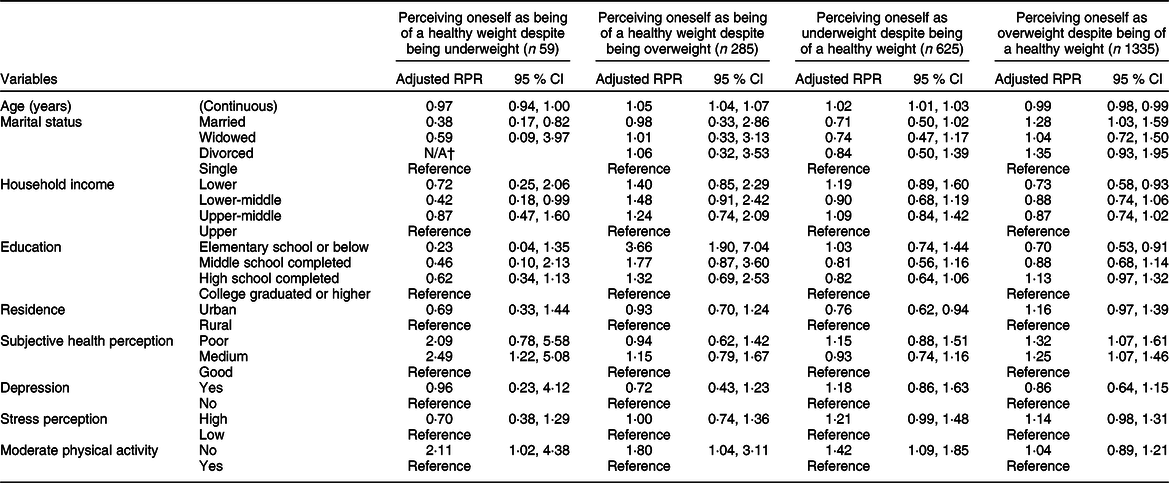

Women whose household income levels were in the lower-middle range were less likely to perceive themselves as being of a healthy weight despite being underweight relative to those whose household income levels were high (RPR = 0·42, 95 % CI 0·18, 0·99; Table 4). Women whose subjective health status was medium were 2·49 times more likely to perceive themselves as being of a healthy weight despite being underweight than those whose subjective health status was good.

Table 4 Multinomial logistic regression results examining factors associated with body weight misperception in women*

RPR, relative prevalence ratios; N/A, not available.

* ‘Self-perception is concordant with the objective status’ is the reference category.

† Due to the reason that the number of divorced women in the category ‘Perceived as being normal weight despite being underweight’ is zero.

As in men, every 1-year increase in age increased the RPR of participants perceiving themselves as being of a healthy weight despite being overweight by 1·05 (95 % CI 1·04, 1·07). A lower educational level was a predictive factor for participants perceiving themselves as being of a healthy weight despite being overweight. However, only the RPR for ‘elementary school or below’ was statistically significant (RPR = 3·66, 95 % CI 1·90, 7·04). Women who engaged in regular physical activity were 1·80 times more likely to perceive themselves as being of a healthy weight despite being overweight than those who did not engage in regular physical activity.

Every 1-year increase in age increased the RPR of participants perceiving themselves as underweight despite being of a healthy weight by 1·02 (95 % CI 1·01, 1·03). Living in an urban area decreased the RPR of participants perceiving themselves as underweight despite being of a healthy weight by 0·76 (95 % CI 0·62, 0·94). Women who engaged in regular physical activity were 1·42 times more likely to perceive themselves as being of a healthy weight despite being overweight relative to those who did not engage in regular physical activity. Unlike in other body image categories, age operated in opposite direction for perceiving as being overweight despite being of a healthy weight. Every 1-year increase in age decreased the RPR of participants perceiving themselves as overweight despite being of a healthy weight by 0·99 (95 % CI 0·98, 0·99). Married women were 1·28 times more likely than single women to perceive themselves as overweight despite being of a healthy weight. Women whose household income levels were low (RPR = 0·73, 95 % CI 0·58, 0·93) and whose educational level was elementary school or below (RPR = 0·70, 95 % CI 0·53, 0·91) were least likely to perceive themselves as overweight despite being of a healthy weight. In contrast, women whose subjective health status was poor (RPR = 1·32, 95 % CI 1·07, 1·61) or medium (RPR = 1·25, 95 % CI 1·07, 1·46) were less likely to perceive themselves as overweight despite being of a healthy weight than those whose subjective health status was good.

Discussion

The current study aimed to explore factors related to body weight misperception in men and women and demonstrated significant implications for addressing health problems originating from body image. The tendency towards over- or underestimation was the same as that observed in previous studies(Reference Steenhuis, Bos and Mayer54). Regarding gender differences in factors related to body weight misperception, only a few factors were common in both men and women (age and education for participants perceiving themselves as being of a healthy weight despite being overweight; subjective health perception for participants perceiving themselves as overweight despite being of a healthy weight). In previous studies involving Koreans, men tended to underestimate their weight and women tended to overestimate(Reference Jang, Ahn and Jeon55,Reference Noh, Kwon and Yang56) . These results are consistent with the results of univariate analysis in our study.

The results indicated that people’s perception of themselves as being of a healthy weight despite being underweight could cause problems such as failure to take action because they believe that they are of a healthy weight despite weakness and decreased muscle, particularly in older men(Reference Bernstein and Munoz57). In women, higher economic status, poorer subjective health status and lack of physical activity were related to this unhealthy perception. In women whose income levels are high, it is possible that the subjective standard for ideal body weight has decreased, prioritising a lower body weight(Reference Bainbridge58). This could be problematic, in that even though their health status is not good and the fact that they are underweight could be related to poor health status, they could fail to consider their body weight a sign of abnormal health status and take no action(Reference Barrett-Connor, Edelstein and Corey-Bloom59,Reference Park, Lee and Han60) .

Even though relations between social class and body image are unclear because of the inconsistent or conflicting findings(Reference Grogan7,Reference Kashubeck-West, Huang and Liu61) , our study found that, unlike men, the subjective yardstick for healthy weight tends to be biased towards slim body shape in women. In relation to social class and body image, psychology studies have found that body shape ideals are very similar in people of different social classes in affluent Western cultures(Reference Grogan7).

As a reason for this result, it can be inferred that women in the higher social class have stronger peer pressure on slim bodies as there are more slim women in their social class than in the lower social class(Reference Moore, Stunkard and Srole62). In the randomised experimental study to investigate the impact of peer pressure to be thin on young women, it was found that exposure to peer pressure to be thin resulted in greater body dissatisfaction(Reference Stice, Maxfield and Wells63). For adolescents, a prospective study identified the impact of peer pressure on body dissatisfaction(Reference Helfert and Warschburger64).

Because the perception of body size varies depending on the culture, so the results of the current study may be limited in generalisation. For example, in the Middle East and North Africa or Sub-Saharan African regions, it was found that there were regions in which overweight women were optimistic about being overweight and even thought that overweight women were more beautiful(Reference Draper, Davidowitz and Goedecke65–Reference Holdsworth, Gartner and Landais67). On the other hand, in a study of Tunisian women in North Africa, a region closer to the continental Europe, it was reported that Tunisian women did not prefer larger body sizes in spite of the Arab-Muslim culture in which large body sizes for women are seen as desirable and associated with female beauty(Reference Tlili, Mahjoub and Lefèvre68).

In the scoping review to explore the associations between physical activity, sport and body image, it was found that participation in physical activity and sport was related to less negative and more positive body image(Reference Sabiston, Pila and Vani69). In our study, only women have shown the same results. In the study to explore the theoretical model on the mediation of body image and physical self-concept in adolescents, authors suggested that physical activity can help individuals to achieve a positive self-concept and promote psychological well-being through the improvement of physical perceptions and body satisfaction(Reference Fernández-Bustos, Infantes-Paniagua and Cuevas70).

Perceiving oneself as being of a healthy weight despite being overweight could lead to failure to attempt to control one’s body weight, remaining overweight(Reference Robinson71). Recently, there have been studies that have made health professionals agonise over the health implications of body weight misperception. Contrary to commonly held thoughts, weight misperception among youth who were overweight or obese predicted lower future weight gain(Reference Sonneville, Thurston and Milliren16). In some studies that analysed longitudinal data, participants who perceived their weight status as being overweight were at an increased risk of subsequent weight gain(Reference Robinson, Hunger and Daly72,Reference Robinson, Sutin and Daly73) . As a psychological explanation for this phenomenon, identifying oneself as overweight may act independently of BMI to contribute to unhealthy profiles of physiological functioning and impaired health over time(Reference Daly, Robinson and Sutin74). Even in a systematic review of the relationship between weight status perceptions and weight loss attempts, strategies, behaviours and outcomes, it was found that individuals who perceive their weight status as overweight are more likely to report attempting weight loss but over time gain more weight(Reference Haynes, Kersbergen and Sutin75). In a previous study involving Koreans, subjects with overestimated body image had lower OR for physical activity(Reference Chun, Ryu and Park76). Therefore, it is conceivable that it cannot be guaranteed that correct body perception will necessarily lead to desirable health behaviours. In particular, it suggests that careful intervention on the psychological state of an individual as well as demographic and sociological aspects may be necessary in health interventions for those who perceive that they are overweight.

In the current study, low socio-demographic status (i.e., household income, educational level and residence) and good subjective health status were related to this unhealthy perception in men. The reason for the finding that good subjective health status was related to misperception in men could have occurred because they were less tolerant of their weight as they were in good subjective health. In women, older age, lower educational level and lack of physical activity were related to this kind of misperception. Previous studies have reported that older age(Reference Bhanji, Khuwaja and Siddiqui77,Reference Amaro-Rivera and Carbone78) , male sex(Reference Choi, Bender and Arai79), low educational level(Reference Choi, Bender and Arai79) and living below the poverty line(Reference Amaro-Rivera and Carbone78) were associated with this kind of body image misperception.

Perceiving oneself as underweight despite being of a healthy weight could prompt efforts to increase body weight, resulting in excess weight. In the current study, men who were single, of lower economic status and with lower educational levels were more vulnerable to this unhealthy perception. In women, older age, living in a rural area and lack of physical activity increased the likelihood of this kind of misperception.

Perceiving oneself as overweight despite being of a healthy weight has been associated with some eating disorders(Reference Farrell, Lee and Shafran80,Reference McCabe, McFarlane and Polivy81) , unnecessary weight loss attempts(Reference Kim and Lee82) and higher risk of weight gain(Reference Haynes, Kersbergen and Sutin75). In the current study, men who perceived their health as poor were more vulnerable to this unhealthy perception. In women, younger age, being married, higher socio-economic status, higher educational levels and poor perceived health were predictors of this kind of misperception. The reason for this phenomenon could be that being married, economically stable and highly educated could be a favourable socio-economic condition for the pursuit of a slimmer body despite healthy weight. The result of our study is accordance with the previous study in which married women perceived themselves as overweight than unmarried women(Reference Klos and Sobal41). Age(Reference Park, Cho and Choi83), poorer subjective health perception(Reference Park, Cho and Choi83) and ethnicity (white)(Reference Schieman, Pudrovska and Eccles84,Reference Bhuiyan, Gustat and Srinivasan85) were previously associated with this kind of misperception. In relation to ethnicity, the comparison between white and black is predominant in most studies, so further research is needed on the relationship between body weight perception and ethnicity.

Overall, disadvantageous socio-economic status was considered a predictor of participants’ misperceptions of themselves as being of a healthy weight despite being overweight and as underweight despite being of a healthy weight, mainly in men. In contrast, favourable socio-economic status was considered a predictor of participants’ misperception of themselves as being of a healthy weight despite being underweight and as overweight despite being of a healthy weight, mainly in women. Living in an urban area was an independent predictor of men’s misperception of themselves as being of a healthy weight despite being overweight and women’s misperception of themselves as underweight despite being of a healthy weight. Physical inactivity was a predictor of most misperceptions in women. However, psychological variables, such as stress perception and depression, were not significant predictors of misperception in the current study.

The current study had the following strengths. It was reliable in that interpretation involved representative samples. In addition, the sample size was sufficient to make it possible to analyse by gender. Further, the independent meanings of variables were reviewed in men and women by analysing them using relatively diverse aspects of demographic and sociological variables. However, the study had the following weaknesses. First, because the data were not from a study designed solely for the subject matter in the study, it was inevitable that the types of variable available were limited. In particular, it is regrettable that sociological variables, such as social networks, social support and social pressure, and in-depth psychological variables could not be examined. Second, since the current study is a cross-sectional study, there are limitations in discussing the causal relationship between variables such as subjective health status, stress and physical activity and body weight misperception. Third, in the category of ‘Perceiving oneself as being of a healthy weight despite being underweight’, the multivariate analysis showed a very wide CI, taking a distant range from 1 (especially in men). This is presumed to be due to the relatively small number of samples in the category of ‘Perceiving oneself as being of a healthy weight despite being underweight’. As a result, there is a possibility that the weakened statistical power caused some statistically significant results to be insignificant.

The results of the current study suggest that there are significant differences in factors related to various types of body image misperception between men and women. These differences appeared not only in socio-demographic variables but also in subjective health perception and physical activity. As there have been reports that the effect on the health of body image misperception is not one-sided, tailored approaches may be needed, focusing on the fact that weight-related problems also do not have a uniform pattern between men and women. The problem related to body image should be regarded as a multidimensional issue in which misperception types, related factors and gender are intertwined.

Acknowledgements

Financial support: None. Conflict of interest: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest. Authorship: K.P. designed the study and S.Y.K. and K.P. conceived the analysis question and conducted the analysis. S.Y.K. and K.P. critically revised the manuscript content. All authors were involved in the writing of the manuscript at draft and approved the final version. Ethics of human subject participation: All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The survey, KNHANES VII, was approved by the institutional review board at the Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Informed consent: Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.