Children with special healthcare needs (SHCN) are children aged 0–17 years who ‘have or are at increased risk for chronic physical, developmental, behavioral or emotional conditions and who also require health and related services of a type or amount beyond that required by children generally’(Reference McPherson, Arango and Fox1). Families including children with SHCN experience multiple economic hardships(Reference Shattuck and Parish2,Reference Parish, Shattuck and Rose3) and disproportionately drive healthcare utilisation and spending among children(Reference Newacheck and Kim4). Broadly, elevated hardships in this population appear to be driven primarily by the added direct (e.g. co-pays and co-insurance, equipment, support services) and indirect (i.e. time demands and associated opportunity loss) costs of addressing various healthcare and related needs(Reference Shattuck and Parish2,Reference Parish, Shattuck and Rose3) .

Food-related hardships, in particular, are associated with poor health outcomes(Reference Gundersen and Ziliak5) and increased healthcare utilisation(Reference Tarasuk, Cheng and de Oliveira6) generally, but evidence among children with SHCN is limited. Preliminary evidence from studies in focused geographic areas suggests children with SHCN are more likely to experience household food insecurity, and household food insecurity may affect healthcare outcomes in this population(Reference Adams, Hoffmann and Rosenberg7–Reference Sonik, Parish and Ghosh9). A study of 2-year-old children in Oregon has found that SHCN status is associated with 2·6–2·9 times the odds of experiencing household food insecurity(Reference Adams, Hoffmann and Rosenberg7). In another study among children with SHCN in a single urban area, household food insecurity was associated with nearly twice the odds of having unmet healthcare needs, although associations with emergency department utilisation and hospital admissions were not statistically significant(Reference Fuller, Brown and Grado8). In a national sample, children with disabilities (a group related to but distinct from children with SHCN) faced an elevated burden of household food insecurity(Reference Sonik, Parish and Ghosh9). More broadly, experiences of household food insecurity among children – regardless of SHCN status – is associated with poorer outcomes on general and specific health indicators(Reference Gundersen and Ziliak5,Reference Cook, Frank and Levenson10) , as well as greater odds of being hospitalised(Reference Cook, Frank and Levenson10).

Despite these findings, neither the prevalence of food-related hardships nor the relationship between such hardships and health or healthcare outcomes has been reported among children with SHCN in a nationally representative sample. The National Research Council concluded that there was a dearth of robust evidence on the correlates, causes and consequences of food-related hardships for children with disabilities(11). We sought to provide evidence on these topics using the nationally representative National Survey of Children’s Health, which includes a measure of household food insufficiency (we note here that household food insufficiency is a conceptually narrower measure of food-related hardship than household food insecurity, as the latter incorporates both experiencing food insufficiency and concerns related to the potential risks of experiencing food insufficiency)(Reference Scott and Wehler12). We hypothesised that (1) children with SHCN would be more likely than children without SHCN to experience household food insufficiency; (2) household food insufficiency would be associated with worse health status and greater emergency healthcare utilisation among all children; and (3) the association between household food insufficiency and both health status and emergency healthcare utilisation would be stronger among children with SHCN compared to children without SHCN.

Methods

Data

We analysed pooled data from the 2016 and 2017 iterations of the nationally representative National Survey of Children’s Health, which were the first survey versions to measure household food insufficiency. The surveys were conceptualised by the Health Resources and Services Administration’s Maternal and Child Health Bureau and administered by the US Census Bureau(13). Starting in 2016, the survey combined elements from the previously separate National Survey of Children’s Health and National Survey of Children with Special Healthcare Needs(13). Randomly selected households were contacted by mail and invited to participate in the survey if there were any children <18 years of age present (if multiple children were present, one was randomly selected, with the exception that younger children and children with SCHN were oversampled)(13). Participants then completed surveys online or via mail, depending on their preference. Probability weights were calculated such that the sample would be representative of non-institutionalised 0–17-year-old children in the United States(13). The weighted response rates were 40·7 % in 2016 and 37·4 % in 2017, with respective sample sizes of 50 212 and 21 599 (total n 71 811).

Measures

SHCN status was determined using a validated screener(Reference Bethell, Read and Stein14). The screener utilises five items that ask about a child’s need or use of medicine; greater-than-average need or use of medical/mental healthcare or educational services; limitations regarding abilities common to other children the same age; need for specialised therapy; and emotional, developmental or behavioural problems that require treatment or counselling. If an affirmative response is noted for any of these items – and if a parent or guardian notes that the affirmative reply is due to an underlying condition expected to last at least a year – then the child is identified as having SHCN. In total, there were 16 304 children with SHCN (weighted, 18·8 %) and 55 507 children without SHCN (weighted, 81·2 %) in the sample.

Dependent variables

Household food insufficiency was measured using a single item, which asked whether the respondent could afford the food they needed over the previous year. There were four potential responses: ‘we (i.e. the respondent and others in their household) could always afford to eat good nutritious meals’; ‘we could always afford enough to eat but not always the kinds of food we should eat’; ‘sometimes we could not afford enough to eat’ and ‘often we could not afford enough to eat’. Having any of the latter three responses to this measure has been associated with measurably worse health outcomes(Reference Gregory and Coleman-Jensen15), and so we used a dichotomised version of this variable in our multivariate models that distinguished between no household food insufficiency and any household food insufficiency.

Parents could report a child’s health status as excellent, very good, good, fair or poor. For adults, dichotomising this measure as good or better v. fair or poor is associated with mortality(Reference McGee, Liao and Cao16). However, the most appropriate dichotomisation for children was not assessed. In our multivariate models, we dichotomised this variable as excellent v. less-than-excellent for two reasons: first, this dichotomisation was the most strongly correlated with emergency healthcare utilisation, indicating a greater predictive value for healthcare outcomes; and second, there was a relatively low prevalence of children with fair or poor health.

Finally, we defined emergency healthcare utilisation as having visited a hospital emergency room once or more in the previous year. This variable was derived from an item asking if a child had visited the emergency room ‘never’, ‘1 time’ or ‘≥2 times’ in the past 12 months.

Covariates

We utilised demographic covariates, including age, gender, race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, non-Hispanic other or Hispanic) and income in relation to the federal poverty level. Participation in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP, formerly the Food Stamp Program) at any time in the previous year was also measured. However, given the endogeneity concerns with assessing the effects of SNAP(Reference Kreider, Pepper and Gundersen17), we did not include this measure in our final models (sensitivity analyses including this variable did not alter findings). Participation in the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants and Children and school lunch programmes were not relevant for all age groups and were excluded. Finally, we included measures of whether or not someone smoked inside the child’s home, whether or not the child had health insurance for all of the previous year and whether or not the child had any unmet medical or mental healthcare needs in the previous year, given strong associations between these factors and health and healthcare outcomes.

Analyses

We first conducted bivariate comparisons of children with and without SHCN on demographic variables and other covariates. We made similar comparisons on each of the dependent variables. We also conducted sub-analyses for children in households with income <200 % of the federal poverty level as a sensitivity analysis to assess whether results were primarily driven by the lower income that households with children with SHCN are known to have(Reference Shattuck and Parish2,Reference Parish, Shattuck and Rose3) . Finally, we estimated multivariate logistic regression models for each dependent variable (again including sub-analyses with low-income households). Our models adjusted for all covariates except for SNAP participation as described above. In models with child’s health status and emergency healthcare utilisation as dependent variables, we also included interactions between household food insufficiency status and SHCN status. Also, in the models with emergency healthcare utilisation as the dependent variable, we included health status as an additional covariate. Given the limitations regarding the interpretation of interaction terms in logistic regression models, we also calculated marginal predicted probabilities to assess the average effects of SHCN status, household food insufficiency and their interaction. We used Stata (version 15.1) for all analyses, and all analyses utilised weights provided by the survey.

Results

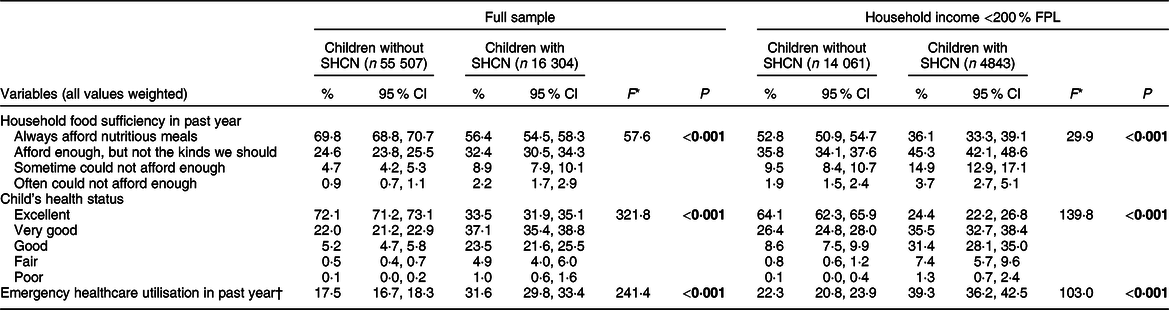

Descriptive comparisons of children with and without SHCN are presented in Tables 1 and 2. Children with SHCN were about 2 years older on average than children without SHCN (Table 1). Children with SHCN were more likely to be boys, be non-Hispanic black, be non-Hispanic generally, live in a low-income household, live in a household receiving SNAP benefits, have unmet medical or mental healthcare needs (despite being slightly more likely to have health insurance) and live in a household where smoking occurred (Table 1). Additionally, children with SHCN were more likely to live in a household experiencing any level of food insufficiency, to have less-than-excellent health status and to have any emergency healthcare utilisation, in both the entire sample and among a subsample of children living in households with income <200 % of the federal poverty level (Table 2).

Table 1 Demographic characteristics of children with and without special healthcare needs (SHCN) in pooled data from the 2016 and 2017 National Survey of Children’s Health

FPL, federal poverty level (United States); SNAP, Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program.

Bold values represent P-value, if P < 0.05.

* Stata (version 15.1) utilises design-based F-tests for weighted comparisons.

† Any participation in the past year indicated receipt.

‡ Health insurance coverage for all of the past year indicated insured status.

§ Having any unmet medical or mental healthcare needs in the past year indicated an unmet care need.

‖ If someone living in the child’s household used cigarettes, cigars or pipe tobacco and smoked inside the home, then ‘smoking in house’ was indicated.

Table 2 Household food insufficiency, child’s health status and emergency healthcare utilisation by special healthcare needs (SHCN) status and income in pooled data from the 2016 and 2017 National Survey of Children’s Health

FPL, federal poverty level (United States).

Bold values represent P-value, if P < 0.05.

* Stata (version 15.1) utilises design-based F-tests for weighted comparisons.

† One or more visits to a hospital emergency room indicated utilisation of emergency healthcare.

Raw results from weighted logistic regression models using both all children and only those in households with income <200 % of the federal poverty level are presented in Table 3. Marginal predicted probabilities stemming from these models are presented in Table 4 to facilitate interpretation of regression results. Utilising these probabilities, we found SHCN status was associated with a 31·7 % increase in the probability of exposure to any household food insufficiency (from 30·8 % (95 % CI 29·9, 31·7) to 40·6 % (95 % CI 38·8, 42·3); Table 4). Household food insufficiency was associated with an 18·5 % decrease in the probability of having excellent health status among children without SHCN (from 76·9 % (95 % CI 75·7, 78·1) to 62·7 % (95 % CI 60·9, 64·4)), as compared to a 36·7 % decrease among children with SHCN (from 41·1 % (95 % CI 39·2, 42·9) to 26·0 % (95 % CI 23·6, 28·3); Table 4). Finally, household food insufficiency was associated with a 19·3 % increase in the probability of having any emergency healthcare utilisation among children without SHCN (from 16·8 % (95 % CI (15·6, 17·9)) to 20·0 % (95 % CI 18·6, 21·3)), as compared to a 16·5 % increase among children with SHCN (from 26·6 % (95 % CI 24·7, 28·5) to 31·0 % (95 % CI 27·8, 34·2); Table 4). Relative values from models that were restricted to children living in households with income <200 % of the federal poverty level were similar.

Table 3 Weighted logistic regression models for household food insufficiency, excellent child’s health status and emergency healthcare utilisation

FPL, federal poverty level; SHCN, special healthcare needs; FI, household food insufficiency.

† Constant term omitted from table.

‡ Any FI indicated any response other than that the household ‘could always afford to eat good nutritious meals’ over the past year.

§ SCHN × FI indicated an interaction between SHCN status and the presence of any FI.

‖ Health insurance coverage for all of the past year indicated insured status.

¶ Having any unmet medical or mental healthcare needs in the past year indicated an unmet care need.

†† If someone living in the child’s household used cigarettes, cigars or pipe tobacco and smoked inside the home, then ‘smoking in house’ was indicated.

*P < 0·05; **P < 0·01; ***P < 0·001; Bold values represent P-value, if P < 0.05.

Table 4 Marginal predicted probabilities* derived from weighted logistic regression models for household food insufficiency, excellent child’s health status and emergency healthcare utilisation

FPL, federal poverty level; SHCN, special healthcare needs; FI, household food insufficiency.

* Predicted probabilities were calculated using the margins command in Stata (version 15.1).

† Any FI indicated any response other than that the household ‘could always afford to eat good nutritious meals’ over the past year.

Discussion

In a nationally representative sample, and compared to other children, we found that children with SHCN have elevated risks of exposure to household food insufficiency, less-than-excellent health status and emergency healthcare utilisation, all despite being slightly more likely to have health insurance coverage. We also found that exposure to household food insufficiency was associated with a greater reduction in the probability of experiencing excellent health among children with SHCN v. children without SHCN. Associations between household food insufficiency and increased emergency healthcare utilisation were similar in both groups, suggesting SHCN status and household food insufficiency are independent risk factors for increased healthcare utilisation. This in itself is notable: the independent nature of these risk factors means that the elevated levels of exposure to household food insufficiency among children with SHCN are more troubling than they would be if SHCN status subsumed some or all of the effects of household food insufficiency on emergency healthcare utilisation (i.e. through a negative interaction). The presence of such an interaction was plausible given the much greater baseline levels of emergency healthcare utilisation among children with SHCN, but it was not found here. Further, our finding that household food insufficiency was associated with a significantly increased likelihood of emergency healthcare use among children with SHCN differed from a prior study that suggested no such association (although that prior study was limited to a single city)(Reference Fuller, Brown and Grado8).

The parent-reported nature of the data in the National Survey of Children’s Health utilised here was a limitation. Consequently, social stigmas related to health conditions and economic hardships may have led to underreporting of these phenomena. Also, the generalisability of the survey to children in households with parents who are immigrants and/or do not speak English has been questioned(Reference Warden, Yun and Semere18), potentially leading to undercounts of groups with heightened social vulnerabilities(Reference Rubio, Grineki and Morales19). Such misclassifications and under-representations, however, would have conservatively biased the results by making the relevant comparison groups appear more similar than they were. Additionally, the household food insufficiency measure in the survey was not as broad or nuanced as common measures of household food insecurity, which capture concerns about having adequate amounts of culturally acceptable food while the measure used here does not(Reference Scott and Wehler12). Potential assessments of experiences of food-related hardships that did not rise to the level of directly experiencing household food insufficiency were thus not possible. It is possible that these less severe food-related hardships are more common and less stigmatised, leading to a greater statistical power and more accurate data for comparisons using such a measure. However, given that a prior study using a more robust household food insecurity measure has found that child disability status was associated with food-related hardships (similar to our findings here)(Reference Sonik, Parish and Ghosh9), it is unlikely that using such a measure would have qualitatively altered our results.

Our findings are quite troubling. Children with SHCN represent a vulnerable population requiring public policy interventions. Some children with SCHN also have specialised nutritional needs that can specifically add to the expenditure on food, further increasing the risk of household food insufficiency specifically(Reference Marjerisson, Cummings and Glanville20). SHCN status is defined by a greater need for healthcare services, but – consistent with prior findings(Reference Shattuck and Parish2,Reference Parish, Shattuck and Rose3) – we found this population to have elevated social vulnerabilities despite mostly having health insurance coverage. While health insurance coverage is surely important, particularly given the elevated medical expenses and out-of-pocket expenditures incurred by families raising children with SHCN(Reference Shattuck and Parish2,Reference Parish, Shattuck and Rose3) , this finding suggests that policy solutions beyond the healthcare system may be needed. Moreover, the social ill examined here – household food insufficiency – was associated with risks to these children’s health and healthcare outcomes over and above the risks caused by their underlying conditions directly. A deleterious cycle is possible if a child with SHCN’s baseline need for healthcare services increases vulnerability to household food insufficiency in such a way that worsens nutrition and health and then further increases the child’s need for healthcare services. We were unable to explore such cycles given the cross-sectional nature of the data, but future longitudinal studies should examine this possibility (including the role of hardships such as household food insufficiency in increasing the likelihood of developing SHCN such as type 2 diabetes in the first place). Regardless, successful interventions will need to account for the potential of such cycles and the complex relationships between social ills and health-related needs among children with SHCN.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: None. Financial support: This research was supported in part by the US Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service. The findings and conclusions of this publication are those of the authors and should not be construed to represent any official USDA or U.S. Government determination or policy. Dr. Sonik was also supported by grant number R03HS026317 from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Conflict of interest: None. Authorship: R.A.S., A.C.-J. and S.L.P. formulated research questions and designed research; R.A.S. analysed the data; R.A.S., A.C.-J. and S.L.P. wrote the article; R.A.S. had primary responsibility for final content; R.A.S., A.C.-J. and S.L.P. interpreted the findings. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. Ethics of human subject participation: Only de-identified secondary data were used and the project was deemed to meet the criteria for Exemption 4.