Nuts are nutritious and provide several health benefits(Reference Afshin, Micha and Khatibzadeh1–Reference Nishi, Viguiliouk and Blanco Mejia5), but intake remains low, partly due to concerns among consumers and health professionals about their high energy content contributing to weight gain(Reference Brown, Tey and Gray6–Reference Pawlak, London and Colby14). However, such concerns are not supported by scientific evidence(Reference Nishi, Viguiliouk and Blanco Mejia5,Reference Akhlaghi, Ghobadi and Zare15,Reference Guarneiri and Cooper16) . The lack of association between nut intake and body weight may be partially explained by their lower-than-expected (up to 30 % lower) metabolisable energy due to incomplete fat absorption(Reference Nikodijevic, Probst and Tan17). Therefore, strategies that address these misconceptions, such as informing consumers of metabolisable energy of nuts, may promote nut consumption.

In Australia, nutrition information on packaged food and beverage products is regulated by Food Standards Australia New Zealand and can be presented as nutrition information panels (NIP) and front-of-pack (FOP) labels, among other elements(18). Currently, in Australia and other countries such as the USA and the European Union, the energy values on labels must be determined using Atwater factors (17 kJ/g of carbohydrate and protein, 37 kJ/g of lipid and 29 kJ/g of alcohol)(19–Reference Roberts and Flaherman21). However, this provides an estimation of the energy content and may not represent metabolisable energy, or the energy that is absorbed by the body during digestion. While some countries such as the USA allow the analysed energy content in NIP to be up to 20 % above the labelled energy value(22), there is currently no allowable margin of error for reporting energy content in NIP in Australia(20). Therefore, the inclusion of nut metabolisable energy in NIP and FOP labels should be explored in Australia.

However, limited research explores perceptions of nut metabolisable energy labelling and the potential impact on nut consumption. We previously conducted an online survey to investigate perceptions of communicating metabolisable energy of nuts on nutrition labels (Nikodijevic et al., in press(Reference Nikodijevic, Probst and Tan23)). This current study aimed to expand on the survey findings by qualitatively exploring perceptions among consumers and stakeholders.

Methods

Study design, researcher position and reflexivity

A qualitative study design utilising focus groups and key informant interviews was conducted among nut consumers and stakeholders. Online focus groups and interviews explored the perceptions of nuts and nut butters, barriers to intake and nutrition labelling.

Thematic analysis of the data was inductive and reflexive, and the study’s underpinnings draw on constructs of the knowledge-to-action framework(Reference Field, Booth and Ilott24). The knowledge-to-action framework consists of two cycles: knowledge creation and an action cycle. It details a structured approach that translates knowledge to practice. This framework was chosen to explore how knowledge about nut metabolisable energy may influence consumer behaviour among a diverse range of participants, including consumers, health professionals and nut growers. Concepts explored what participants thought about the energy content of nuts, if they were aware of their lower metabolisable energy and whether nut metabolisable energy would have a perceived impact on nut consumption.

All authors were accredited practising dietitians with varying levels of experience in academia and clinical practice and were included in the research team due to their experience in nut research, energy balance, nutrition labelling and qualitative research. The moderator (C.J.N) was a PhD candidate at the time of the study, with previous nut-related research experience, and had experience in providing nutritional care to consumers in a clinical context. Throughout the study, the authors discussed their positions and how they may influence data collection and analysis. Reflexive practice was used to identify and manage potential biases that may arise due to the authors’ positions. The moderator kept notes throughout the data collection and analysis phases. Discussions between the moderator and observer (E.P.N, C.M or S.A) occurred following each session to debrief and reflect on the conduct and results of sessions, which helped improve future sessions (such as by rewording questions).

Participant recruitment

Participants were recruited via email from respondents to the prior online survey in 2023 who were interested in a focus group or interview (Nikodijevic et al., in press(Reference Nikodijevic, Probst and Tan23)). Survey respondents were recruited using social media, e-newsletters and community flyers distributed in the Illawarra region of New South Wales and the main University of Wollongong campus. Eligible respondents needed to be living in Australia and be aged 18 years or older. The design of the online survey is detailed elsewhere (Nikodijevic et al., in press(Reference Nikodijevic, Probst and Tan23)). Briefly, consumers included in this study had no formal nutrition training, while stakeholders had formal nutrition training and were working as a dietitian, nutrition professional, nutrition and food science researcher, public health professional, food industry professional, food regulator or nut grower. As an incentive, a prize draw to win one of five $50 supermarket vouchers was established. Ethics approval was obtained from the University of Wollongong Health and Medical Human Research Ethics Committee (2022/341). All participants provided written informed consent prior to participation. No participants refused to participate in or dropped out of this study.

Data collection

All focus groups and key informant interviews were conducted online using Zoom (version 5.17.5; https://zoom.us). Focus groups included two to four participants per group, while key informant interviews were conducted one-on-one. The allocation of participants to the focus groups or interviews was based on participant availability. A demographic questionnaire collected information about age, gender, education, employment status and geographical area of residence, as well as profession, highest qualification, years working in current role and geographical area of work for stakeholder participants.

Focus groups and interviews were conducted by one moderator (C.J.N., woman), and one observer (E.P.N., C.M. or S.A., all women) present where possible. The moderator was the primary investigator and a novice qualitative researcher, while E.P.N. had prior experience in qualitative research and focus group methodology. The remaining two observers (C.M. and S.A.) were novice qualitative researchers. The moderator and observers were trained dietitians with 2–15 years’ of experience. The questions followed a semi-structured approach, with follow-up questions asked as appropriate (see online supplementary material, Supplemental Material 1). Questions were pilot-tested with a group of four consumers and modified according to feedback. As outlined by Krueger and Casey(Reference Krueger and Casey25), each session began with an introduction to the process. Participants were informed in advance of the topics of the session. No repeat interviews were carried out.

Questions were developed by the authors. Briefly, the questions explored nut intake (consumers only), perceptions of nuts and nut butters, current target for nut intake, barriers to nut intake (consumers only), relationship with body weight, metabolisable energy of nuts and the perceived impact this has on consumption and nutrition labelling (using the mock packaging slides). Additionally, for stakeholders, how nut intake is recommended or promoted was also explored. The term ‘metabolisable energy’ was defined as the amount of energy our body can absorb when we eat food prior to the respective questions. Participants were then asked if the lower metabolisable energy of nuts would impact consumption or product choice. Participants were shown examples of mock packaging for plain nuts, a nut butter and a nut-containing breakfast cereal, with either Atwater or metabolisable energy displayed (see online supplementary material, Supplemental Material 2). A metabolisable energy value of 10 % lower than Atwater energy was displayed in packaging for plain nuts and nut butters to reflect the difference in metabolisable energy based on nut types and form (ranging from 5 % to 26 % lower than Atwater). The breakfast cereal example showed a metabolisable energy of 1 % lower than Atwater to reflect the small proportion of nuts within the product. Finally, participants were shown examples of nutrition labelling (see online supplementary material, Supplemental Material 2) and asked to choose their preference and/or suggest other ideas.

All focus groups and interviews were recorded using Zoom and transcribed using Otter Pro (version 3.45.1-240308; https://otter.ai) software. Data cleaning consisted of source data verifying the transcripts to ensure verbatim transcription and accuracy(Reference Houston, Probst and Humphries26). The primary investigator (C.J.N.) compared the Otter transcripts to the respective Zoom recordings (the source data). Data cleaning provided a first opportunity for data immersion and to record initial thoughts, as recommended by Braun and Clarke(Reference Braun and Clarke27).

Data analysis

All investigators were Accredited Practising Dietitians, with two (E.P.N. and Y.C.P., both women) having previous experience in qualitative research, while the remaining (S.Y.T. [man] and C.J.N. [woman]) were novices. Three investigators (E.P.N, Y.C.P. and S.Y.T.) hold a PhD in nutrition and dietetics and worked in academia at the time of the study. The final investigator (C.J.N.) previously obtained a Bachelor degree in nutrition and dietetics and was undertaking a PhD at the time of the study. Inductive, reflexive thematic analysis of the transcripts was conducted by the primary investigator (C.J.N.) as outlined by Braun and Clarke(Reference Braun and Clarke27). In line with the recommendations of Braun and Clarke(Reference Braun and Clarke28), data saturation was not consistent with reflexive thematic analysis and checks were not implemented in this study. Coding was reflexive and systematic to increase robustness during this stage. Codes were stored and managed using NVivo software (release 1.7.1, https://lumivero.com/products/nvivo/) and were gathered to form potential themes. A second researcher (E.P.N.) independently generated codes and themes for two transcripts, which were discussed with the primary investigator before the primary investigator (C.J.N.) coded the remaining transcripts. A coding tree was developed using NVivo and themes were finalised and agreed upon by all investigators through discussion. Quotes are presented to demonstrate each theme, deidentified and labelled according to stakeholder group (e.g. DIET for nutritionist/dietitian), participant age (e.g. 4655 for 46–55 years), gender (e.g. F for female/woman) and number (e.g. DIET4655F1). This study is reported according to the COnsolidated criteria for REporting Qualitative research (COREQ) checklist(Reference Tong, Sainsbury and Craig29), provided in see online supplementary material, Supplemental Material 3.

Results

Participant demographics

Four focus groups and nine key informant interviews were conducted with twenty participants. Fifteen (75 %) were female/women and twelve participants (60 %) were aged 26–45 years. Focus group duration varied 44–54 min, while interviews ran 25–44 min. Forty percent of participants were consumers, and the remainder were key stakeholders (Table 1).

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of participants (focus group, n 11; key informant interview, n 9)

NA, not applicable.

Bold font clearly shows the n numbers, as opposed to %.

* n 8 consumer participants across two focus groups and one interview.

† n 12 stakeholder participants across two focus groups and eight interviews.

‡ At the time of demographic questionnaire development, the gender question was phrased ‘What is your gender?’ and options were ‘Male’, ‘Female’, ‘Non-binary’ and ‘I prefer to self-describe (please specify)’. We acknowledge that ‘male’ and ‘female’ are not terminology used to describe gender and research in health sciences is evolving to recognise correct terminology.

§ Gender abbreviated for deidentified participant labels, e.g. male/man abbreviated to ‘M’.

|| Age range abbreviated for deidentified participant labels, e.g. 18–25 years abbreviated to ‘1825’.

¶ Participant category abbreviated for deidentified labels: ‘Consumer’ abbreviated to ‘CONS’, ‘Nutrition/dietetics’ abbreviated to ‘DIET’, ‘Public health’ abbreviated to ‘PH’, ‘Food industry’ abbreviated to ‘IND’, ‘Food regulation’ not abbreviated due to lack of participants, ‘Nut growing’ abbreviated to ‘NUTG’.

** Participants were instructed to select all options that apply for employment status.

Themes

Five major themes were generated and are discussed below. Illustrative quotes for each theme are presented in Tables 2–6. To allow for comparison between the participant groups, the consumer perspective and stakeholder perspective are presented within each theme.

Table 2. Theme 1: knowledge of nuts varies among consumers and stakeholders, and nuts are perceived to be both healthy and unhealthy

Table 3. Theme 2: nuts are versatile in the diet, yet nut intake is low

Table 4. Theme 3: consumers perceive over-eating nuts will lead to weight gain, while stakeholders highlight the importance of considering the whole dietary pattern

Table 5. Theme 4: nutrition labelling is confusing for consumers and needs to be transparent and positively framed, if used

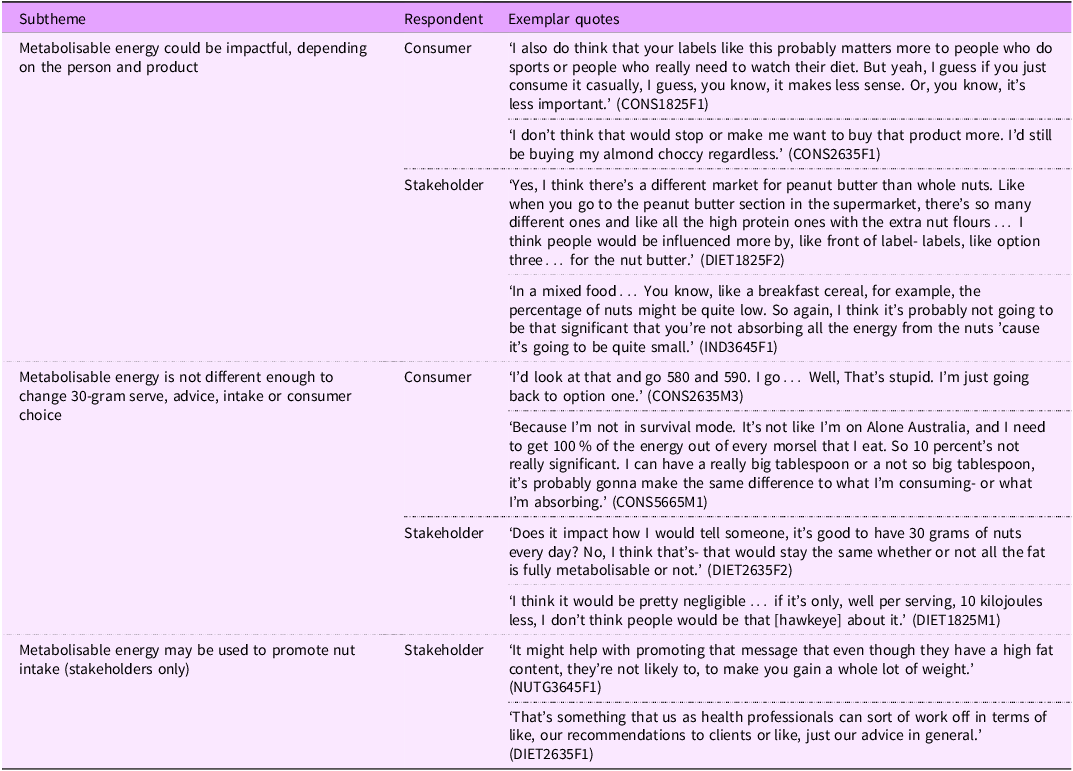

Table 6. Theme 5: knowing nut metabolisable energy will have limited perceived impact on nut consumption and advice

Theme 1: Knowledge of nuts varies, and the healthfulness of nuts is conditional on use and preparation

Consumer perspective

Consumers demonstrated a basic understanding of nuts, including identifying nuts and nut butters and some nutrients they provide. Consumers acknowledged that nuts can be a healthy food, but also believed that there were less healthy nuts, depending on the nut type and how they were processed. For example, raw, organic or unprocessed nuts were viewed as healthier than nuts that were salted or flavoured or processed into nut butters (Table 2). When questioned about the serving size of nuts, most reported ‘a handful’ as appropriate. When participants were informed that for many foods, the human body is unable to digest and absorb all of the energy contained, consumers thought the amount of available energy from nuts varied from about half to all of the energy.

Stakeholder perspective

Compared with the consumer group, stakeholders demonstrated a higher level of knowledge regarding nuts. A variety of stakeholder types were able to identify key nutrients and relationships between nut intake and health. Stakeholders believed that nuts can be included in a healthy pattern of eating and thought of nuts and nut butters as convenient and versatile foods. However, stakeholders made similar comments to consumers regarding the processing of nuts, emphasising raw, unsalted nuts for consumption as opposed to highly processed nuts or nut-containing discretionary products (Table 2). They correctly identified ‘30 grams per day’ as the recommended serve size and frequency for nut consumption, though many noted that ‘a handful’ or a ‘quarter cup’ was an easier message. The term ‘metabolisable energy’ was familiar to stakeholders, and most believed that the metabolisable energy of nuts was less than 100 %. Some recalled learning this information and noted that the high fibre content contributes to the accessibility of fats.

Theme 2: Nuts are versatile in the diet; intake is low

Consumer perspective

Many consumers acknowledged that nuts can be included in the diet in a variety of ways. Consumers believed nuts were a tasty food and that this was an enabler to intake. Other enablers included prioritising a healthy diet and choosing more affordable nut types and products. Some intended but failed to include a handful of nuts every day in their diet, despite nuts being a versatile food and easy to eat more than one handful in one sitting (Table 3). The most common barriers to nut intake were the fat content and the potential for weight gain. Consumers were aware of the high fat and kilojoule content of nuts, and this combined with their ‘more-ish’ (i.e. palatable) nature caused concern for weight gain. The high cost of some nuts was also a barrier; however, consumers acknowledged price variations, and some affordable options were available. Other barriers to regular nut intake included disliking the taste, not being allowed in their children’s school, not being in the habit of buying or eating nuts, not common to the participant’s culture, having a busy lifestyle that restricts snack occasions and a preference for larger meals as opposed one handful of nuts.

Stakeholder perspective

Like the consumer group, stakeholders also perceived nuts to be a versatile food in the diet. Nuts were viewed as a convenient snack option, as well as being incorporated into products. Stakeholders reported that the 30-gram recommendation is achievable; however, due to the variety of foods in a diet, it’s unlikely that consumers choose nuts every day. Stakeholders also reported that taste, choosing more affordable nut types and having discretionary income were other enablers for consumers. Although some believed that nuts were easy for consumers to eat, many agreed that nuts are ‘under-consumed’ and most consumers do not eat 30 grams per day (Table 3). Probable barriers were similar to those reported by consumers, including the perceived high cost and the belief that nuts are unhealthy or lead to weight gain. However, stakeholders also identified a range of other potential barriers to intake, such as disliking the taste, being allergic to nuts, having poor dentition, nuts being forgotten or viewed as a boring food and consumers not being in the habit of buying or eating nuts, or not aware of how to add nuts to the diet.

Theme 3: consumers perceive over-eating nuts leads to weight gain, while stakeholders consider the whole dietary pattern

Consumer perspective

Consumers emphasised the importance of portion control. They believed that small amounts of nuts were considered healthy, and a 30-gram portion of nuts would not affect their body weight. However, consumers acknowledged that nuts are palatable and easy to over-eat, and too many nuts would contribute to weight gain. Eating more than one handful of nuts per sitting was perceived to be ‘overdoing it’ due to the high-fat content. Consumers also noted that people who wish to maintain or lose body weight should limit their nut intake. Some recalled past weight gain that they believed their nut intake had contributed to (Table 4).

Stakeholder perspective

Stakeholders shared similar perceptions to consumers regarding the importance of portioning. It was perceived that the current recommendation of 30 grams of nuts per day would not cause weight gain and may be included by those who wish to maintain their body weight. Reasons for not contributing to weight gain were that nuts help to regulate appetite and that not all of the fats within nuts are absorbed by the body. Nut consumption above the recommendation of 30 grams per day could cause some weight gain (Table 4). One key distinction in opinions was stakeholders’ comments about the need to consider the whole diet, rather than focusing on one food. All reported that body weight is influenced by the overall diet, rather than a single food. The whole diet and lifestyle of an individual need to be evaluated when considering the impact of nuts on body weight.

Theme 4: Nutrition labelling is confusing for consumers and needs to be transparent and positively framed, if used

Consumer perspective

Some consumers report checking NIP for specific nutrients, though others stated that they do not look at the NIP. For those that use NIP, the nutrients that would usually be checked included protein, fats, sugars, Na and energy. For FOP labels, consumers felt these were sometimes used as a marketing trick by the food manufacturer, rather than being a reliable source of nutrition information (Table 5). When asked about their preferences for metabolisable energy of nuts on nutrition labels, consumers liked both NIP and FOP if the information was clearly presented and positively framed (for example, the FOP statement ‘Your body absorbs only 80 % of the energy from nuts!’ was perceived to have a positive tone, as opposed to ‘Your body cannot absorb all of the energy from nuts!’). Most liked seeing the metabolisable energy (as opposed to Atwater energy) in NIP, but preferred both values, with the label explicitly stating which was which. Some were confused by two energy values. For metabolisable energy presented in FOP labels, consumers liked FOP labels that were honest and trustworthy, with a positive tone. It was evident that displaying metabolisable energy on nutrition labels was supported if it was planned for all packaged food and beverage products, not just nuts. Consumers highlighted the importance of being clear and consistent among all food products to avoid confusion about either nuts or energy content. Following this, consumers believed that it may be confusing to display the metabolisable energy of nuts on labels, due to the complex concept making nutrition labels more confusing to read. Consumers were informed that the metabolisable energy differs by nut type, and this was one concern for labelling. Further, displaying percentages in FOP labels was criticised because it meant that consumers would need to calculate the new energy value, and it was confusing whether the NIP had already taken the percentage reduction into account. Furthermore, some consumers stated that metabolisable energy labelling, whether via NIP or FOPs, would not influence which product they chose nor how many nuts they consume. Consumers noted that metabolisable energy labelling may be more useful for other health-conscious people, rather than themselves.

Stakeholder perspective

Many stakeholders believed that consumers typically do not read NIP and would be more likely to be influenced by an FOP label (Table 5). There were varied responses regarding whether consumers would prefer products that show the metabolisable energy of nuts. Some acknowledged that health- or weight-conscious consumers may be more attracted to products showing a lower energy content, but this would not be important for all consumers. Others believed that consumers would prefer products with more energy, especially considering the use and understanding of the term ‘energy’ rather than ‘kilojoules’. Either way, showing metabolisable energy on labels was perceived to be more meaningful for consumers. Stakeholders agreed that nutrition information presented on labels needs to be clear and positively framed. Most thought that nutrition labels are a source of confusion for consumers and emphasised the need to present simple messages that consumers would understand. However, like consumers, stakeholders were more supportive of presenting metabolisable energy on all food products, not nuts alone. Given the perception that nutrition labels are already confusing for consumers, stakeholders reported that consistency in energy labelling is key. Presenting nut metabolisable energy exclusively on nutrition labels was not entirely convincing, and other strategies were suggested. Stakeholders, including dietitians, food industry professionals, public health professionals and nut growers, thought that dietitians could discuss nut metabolisable energy with consumers during consults, or that an education campaign (such as social media) might be more effective. Most were wary of the feasibility of changing nutrition labels and noted that it would be time-consuming and expensive. The complexity of metabolisable energy as a concept was also highlighted, given that it differs by both nut type and by person. Therefore, it was perceived that nutrition labelling may not be the best route to communicate the metabolisable energy of nuts.

Theme 5: Knowing nut metabolisable energy will have limited perceived impact on nut consumption and advice and is dependent on the individual and product

Consumer perspective

Consumers reported that metabolisable energy of nuts could be useful information for some people, even if participants personally would not be influenced by it. People who are conscious about their weight or health may be interested in metabolisable energy and, therefore, choose products that present a lower energy content. The consensus was that preferences for displaying metabolisable energy on nutrition labels is dependent on the individual, rather than for everybody (Table 6). In addition, preferences for displaying metabolisable energy differed by product type. Bags of plain nuts, which may contain one single nut type or several types, were perceived as suitable. For nut butters (where the metabolisable energy is higher than for whole nuts) and products that contain small amounts of nuts, such as a breakfast cereal, presenting the metabolisable energy was perceived to be less helpful. Consumers reported that metabolisable energy labelling could be useful for individual nuts (not multi-ingredient foods), but ideally, energy labelling should be consistent among all food and beverage products.

Stakeholder perspective

Again, it was agreed that the metabolisable energy of nuts may be helpful for some consumers, but not all. Consumers who are health conscious or interested in nutrition were perceived to be more likely to check labels and be influenced by a lower energy value. Stakeholders also believed that metabolisable energy might be more influential for consumers depending on the type of product. Different varieties of peanut butters (such as an extra crunchy butter, or a high protein butter with added nut flours) may benefit from an FOP label showing the metabolisable energy and encourage consumers to purchase. For multi-ingredient foods that contain few nuts, it would be less impactful (Table 6). Many did not believe that consumers would increase their nut intake because of metabolisable energy labelling or think that the recommended 30 grams per day should change. Few had concerns about metabolisable energy encouraging people to ‘over-eat’ nuts (more than 30 g) or increasing their intake of other energy-dense foods. Some reported that the lower metabolisable energy could be useful in promoting nut intake and dispelling the weight gain myth. They agreed that understanding the metabolisable energy of nuts may be useful to health-conscious consumers, but product type (such as whole nuts v. a multi-ingredient product) should be considered. Stakeholders reported that energy labelling must be consistent among all packaged products to prevent confusion.

Discussion

Our study has provided insights into consumer and stakeholder perceptions of energy labelling for nut products. Knowledge of nuts and perceptions around their healthfulness varied. Consuming excess amounts of nuts was perceived to contribute to weight gain; however, stakeholders emphasised the importance of the whole dietary pattern. Presenting the metabolisable energy of nuts on nutrition labels was confusing at times, and participants expressed a need for nutrition labels to be transparent, positively framed and consistent across food groups. In addition, knowing the metabolisable energy of nuts has little perceived impact on nut intake and advice regarding consumption. Overall, these findings suggest that including the metabolisable energy of nuts in nutrition labels may not be a straightforward solution in resolving concerns regarding the impact of nut consumption on body weight, hence other strategies may be needed.

Many participants reported that a small handful of nuts daily is unlikely to contribute to weight gain. However, the importance of portion control was emphasised, with regular intake exceeding 30 g perceived to increase body weight. The high fat and kilojoule content of nuts was a barrier to intake for consumers. Surveys conducted in New Zealand, the United States and Australia have reported consumer concerns regarding the effect of nut consumption on body weight(Reference Pawlak, Colby and Herring11,Reference Yong, Gray and Chisholm13,Reference Pawlak, London and Colby14,Reference Tran30) . These surveys did not specify the portion size of nuts when exploring perceptions relating to weight gain. In comparison, in this study, consumers and stakeholders agree that nuts generally would not impact body weight, if eaten in the recommended 30-gram portion. However, due to the methods in our study, participants were able to expand on their answers and provide reasons why they felt this way, including the importance of not over-eating nuts, which may explain the differences between the previous surveys and our study. The impact of an individual’s diet and lifestyle was also highlighted by stakeholders, overruling the impact of a single food on body weight.

Relevant nutrition information can be relayed to consumers through several methods, such as nutrition consultations, public health messaging and nutrition labels on food packaging. Stakeholder participants in our study believed that consumers do not typically read NIP but may instead be influenced by FOP labels. This contrasted with use reported by consumers, who stated checking NIP on packaged products to review certain nutrient contents, such as sugar, Na or saturated fat. When comparing NIP and FOP labels, consumers had a preference for NIP and viewed FOP labels as a marketing trick. This finding aligns with previous research in Australia and New Zealand, which found FOP labels including claims were often viewed as untrustworthy, whereas NIP were trusted by consumers(31). Taken together with the results of our study, the findings suggest that displaying the metabolisable energy of nuts may be more effective when shown in the NIP as opposed to using FOP claims, in turn aligning with consumers’ trust in nutrition information. Despite consumers generally preferring NIP to communicate metabolisable energy, some liked the concept of using an FOP label alongside an updated NIP to gain attention. Stakeholders agreed that FOP labels could be enticing. A study from 2023 reported that FOP labels that use colour and clearly identify if a product is healthy were useful in assisting consumers to choose healthier options compared to more complex labels(Reference Pettigrew, Jongenelis and Jones32). In our study, some participants viewed the hypothetical FOP labels as a warning or criticism of their body being unable to absorb energy, which dissuaded product choice. The interpretation of these hypothetical labels contributes to the preference for clear, positively framed labels, which may encourage consumers to purchase nuts and nut products, thereby supporting nut intake in line with dietary guidelines.

In addition to considering the individual consumer, the type of product was influential in participants’ preferences for nut metabolisable energy labelling. Consumers and stakeholders agreed that displaying the metabolisable energy of nuts on packaged whole nuts would be appropriate. Since the hypothetical labels were specific to nuts, they were considered transparent and not misleading. However, most participants reported that showing the metabolisable energy on multi-ingredient products would be misleading and unhelpful. Consumers and stakeholders queried the metabolisable energy of other foods, and this explains their preference for nut metabolisable energy labelling for whole nuts only and not for multi-ingredient food products (where metabolisable energy of other ingredients is not known). The complexity of products appears to relate to preferences for nut metabolisable energy labelling, where the more complex a product (multi-ingredient foods or nut butters with added sugars and oils), the less appropriate it becomes to display metabolisable energy of nuts. This differs from another Australian study which found that consumers prefer FOP labels on complex, multi-ingredient products(Reference Thompson, McMahon and Watson33).

The complexity of metabolisable energy as a concept led some participants to reject nut metabolisable energy labelling as a potential strategy to increase nut intake. While participants reported an understanding of metabolisable energy, both groups believed that many consumers would be confused by the hypothetical labels. Hence, metabolisable energy is a complex concept, and labelling may not offer a simple strategy for promoting or increasing nut intake. Consumers and stakeholders commented on the minimal difference between metabolisable energy and the current energy value and did not perceive it to be substantial enough to influence purchasing choice, nor intake. However, in a recent secondary analysis of 2011–12 NNPAS dietary data, there was a significant difference of up to 77 kJ between estimations of energy intake coming from nut intake (11·8 g) using Atwater factors and metabolisable energy(Reference Nikodijevic, Probst and Tan34). While this was statistically significant, the clinical significance of the estimated energy intake from nuts using metabolisable energy must be considered for a 30-gram portion. In the current study, stakeholders believed that many consumers do not use nutrition labels and, as a result, this would not be an effective strategy to increase nut consumption. Furthermore, stakeholders reported that changing nutrition labels is unlikely to be feasible since it is a time-consuming and complex process, and a consistent approach to labelling is required. For these reasons, nutrition labels may not be a straightforward approach, and other strategies should be considered to promote nut consumption.

There are several strengths of our study. A variety of perspectives were captured, including Australian nut consumers, nutrition experts, industry professionals, public health professionals and nut growers. Focus groups and interviews produce data which contribute to a deeper understanding of perceptions compared to quantitative methods, such as a survey. However, some limitations also exist. Participants were recruited from an online survey and were mostly young, educated females, likely interested in either nuts or nutrition. Therefore, the findings of our study may not be generalisable to Australian consumers and stakeholders. While there was diversity in the stakeholder group in terms of profession, only one nut grower participated, and none of the stakeholders worked in food regulation. Further, the small number of public health, food industry and nut grower participants did not allow for meaningful comparison between stakeholder types. Following data collection, member checking was not performed. Implementing both focus group and individual interview methods may have affected responses. For example, one-on-one interview participants did not have the opportunity to consider other perspectives and participate in group discussions. Additionally, some focus groups consisted of only two participants which may have limited discussion among participants. Finally, focus groups are subject to social desirability bias, where participants report ‘socially acceptable’ responses which may not reflect their real-life behaviours or perceptions.

Conclusion

Perceptions of presenting nut metabolisable energy on nutrition labels were multi-layered, suggesting displaying these values may not be a straightforward solution to resolving concerns regarding the impact of nut consumption on body weight. Of note, consistency in nutrition labelling across products is desired, and if using labels to communicate nut metabolisable energy, they should be clear and positively framed. Therefore, randomised controlled trials examining the impact of different labelling elements, and different nut types and nut-containing products are needed to investigate the precise impact of displaying metabolisable energy on consumer food choice and nut intake. Moreover, changing the macronutrient contents (such as fat content) in NIP to reflect metabolisable energy may be explored in future studies.

Supplementary material

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S136898002510058X

Acknowledgements

The authors thank additional research observers Chiara Miglioretto and Shoroog Allogmanny for observations of focus groups and interviews and the University of Wollongong for providing supermarket vouchers.

Financial support

This work was supported by Nuts for Life and Horticulture Innovation Australia Limited (via a matching PhD scholarship which is equally funded by the University of Wollongong and Nuts for Life). Nuts for Life had no role in the design, analysis or writing of this article. This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflicts of interests

C.J.N. receives a matching PhD scholarship which is equally funded by the University of Wollongong and Nuts for Life. Y.C.P. has been previously involved in clinical trials funded by and received funding from the California Walnut Commission, received funding and research support from the Almond Board of Australia, California Walnut Commission and Nuts for Life. S.Y.T. was previously involved in clinical studies that were funded by the Almond Board of California, International Nut and Dried Fruit Council and the California Walnut Commission. E.P.N. has previously received research funding from Nuts for Life, the California Walnut Commission and the International Nut and Dried Fruit Council.

Authorship

C.J.N., Y.C.P, S.Y.T. and E.P.N. formulated the research question and designed the study; C.J.N. conducted the research; C.J.N. and E.P.N. analysed the data; S.Y.T. and Y.C.P. provided insights into the interpretation of the analysed data; C.J.N. drafted the manuscript and Y.C.P., S.Y.T. and E.P.N. provided critical revision of the manuscript.

Ethics of human subject participation

This study was conducted according to the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki, and all procedures involving research study participants were approved by the University of Wollongong Health and Medical Human Research Ethics Committee (2022/341). Written and verbal informed consent was obtained from all subjects/patients. Verbal consent was witnessed and formally recorded.