The study of nutrition and food intake is an acknowledged topic in adolescent health. In the last few years a range of studies have suggested that also meal habits are related to adolescents’ health. Infrequent meal consumption among adolescents is associated with poor diet, overweight and an inability to concentrate in school( Reference Toschke, Kuchenhoff and Koletzko 1 – 11 ). Most of these studies have looked at breakfast consumption while only a few studies have included frequency of other meals( Reference Toschke, Kuchenhoff and Koletzko 1 , Reference Storey, Hanning and Lambraki 2 , Reference Pedersen, Meilstrup and Holstein 4 , Reference Koletzko and Toschke 6 , Reference Sjöberg, Hallberg and Höglund 8 , 11 ). Infrequent lunch consumption is common among adolescents in many countries( Reference Sjöberg, Hallberg and Höglund 8 , Reference Dubuisson, Lioret and Dufour 12 – 17 ) and lunch consumption among adolescents is of interest, given that lunch frequency in adolescence predicts lunch frequency in adulthood( Reference Pedersen, Holstein and Flachs 18 ). Like other health behaviours, infrequent lunch consumption may be more common among specific sociodemographic groups. To adequately address these issues it is important to understand the social patterning of lunch habits. Since most adolescents spend most of their day – including lunch time – at school, the school setting may be an important component in understanding the social patterning of lunch habits.

Few studies have investigated the association between sociodemographic factors and lunch frequency. Those that have been conducted have had variable findings. Among Swedish 14–15-year-olds, no gender or socio-economic differences (measured by an area-level measure of socio-economic position) in lunch frequency was found( Reference Höglund, Samuelson and Mark 19 ). Another study of 15–16-year-olds in Sweden found no differences in lunch frequency by gender, parental education or ethnic background( Reference Sjöberg, Hallberg and Höglund 8 ). A Chinese study among 12–14-year-olds found no differences in lunch frequency by family affluence( Reference Shi, Lien and Kumar 13 ). Abudayya et al. found no age differences in lunch frequency among 12–15-year-olds living in Gaza, but low lunch frequency was more common among boys and adolescents of mothers with low educational levels( Reference Abudayya, Stigum and Shi 14 ). We have not identified any studies on lunch frequency and family structure, but frequent breakfast consumption appears to be more prevalent in two-parent families( Reference Vereecken, Dupuy and Rasmussen 20 – Reference Levin, Kirby and Currie 23 ). In Denmark, there are no gender differences in lunch frequency among adolescents, but lunch frequency appears to decline with increasing age( Reference Pedersen, Meilstrup and Holstein 4 ).

In many countries, adolescents eat lunch at, or near, school, and the school thereby constitutes an important setting for promoting lunch consumption. Still, only a few studies have examined the association between characteristics of the school setting and healthy eating( Reference Story, Nanney and Schwartz 24 – Reference Krølner, Due and Rasmussen 26 ) and the literature on school characteristics and lunch, specifically, is limited. Within the school setting the clustering of students in school classes may also be relevant as students here may be strongly influenced by their classmates’ behaviour, attitudes and beliefs about lunch. This influence could be particularly strong in school systems with stable structures of students belonging to the same school classes throughout ten years of school life. To our knowledge, there have been no studies examining explanatory factors for school or school class differences in student lunch frequency. Neumark-Sztainer et al. found that a school policy allowing students to leave school during lunch breaks was positively associated with lunch consumption at fast-food restaurants( Reference Neumark-Sztainer, French and Hannan 27 ), but it remains unknown if such policies are associated with the overall frequency of lunch consumption. Some studies have found that the provision of lunch at school appears to influence adolescents’ dietary intake( Reference Raulio, Roos and Prättälä 28 , Reference Condon, Crepinsek and Fox 29 ), but no studies have investigated whether availability of a school food stand/canteen influences whether or not students eat lunch. The presence of an adult in the home has been found to be associated with a greater likelihood of eating a healthy lunch( Reference Young and Fors 30 ) but we have not found studies that examine if adult presence during lunch breaks is associated with frequency of lunch consumption. Also, too little time scheduled for lunch breaks at schools may influence lunch frequency as adolescents spend their lunch break on many other activities than eating (e.g. playing football, hanging out with friends, talking and participating in social interactions)( Reference Getlinger, Laughlin and Bell 31 ). Further, availability of a refrigerator for storage of packed lunches may promote lunch frequency. Finally, it is unknown whether predictors of lunch frequency vary by gender and age.

Ecological theory proposes that health behaviours are influenced by several contextual levels such as individual factors (e.g. sociodemographic factors), meso-level factors such as school and family settings, and macro-level factors such as country-level policies( Reference Story, Neumark-Sztainer and French 32 – Reference Golden and Earp 34 ). It has been suggested that these levels may modify the effect of each other( Reference Kremers, de Bruijn and Visscher 35 , Reference Brug, Kremers and Lenthe 36 ). The aim of the present study was therefore to identify sociodemographic and school-level factors that may influence lunch consumption among adolescents. Specifically, the research questions included:

-

1. Does lunch frequency among adolescents vary between schools and between school classes within schools?

-

2. Are individual sociodemographic factors and characteristics of the school associated with lunch frequency?

-

3. Are any observed associations between characteristics of the school and lunch frequency modified by the gender or age of the students?

Methods

The Danish school setting

All Danish children are entitled to schooling at Danish public primary and lower secondary schools. This schooling includes a one-year pre-school class followed by nine years of primary and lower secondary school. Private schools exist where approximately 85 % of the expenses are paid for by the local government and the remaining part is paid for by the parents. Every school in Denmark is governed by a board. The board is elected by and composed of parents of the students within the school. The school headmaster participates in the board meetings but is not a board member. Students usually stay in the same school class throughout the ten years of schooling( 37 ). There is no national provision of school meals. Students are expected to bring a packed lunch from home or buy lunch from the school food stand or canteen, if available. The difference between a food stand and canteen differs from school to school, but a canteen often has a wider selection of food than a food stand and it is possible for the students to sit and eat at the canteen. Approximately 60 % of 11−14-year-old students in Denmark bring a packed lunch from home and this packed lunch often consists of rye bread with cold cuts( Reference Pedersen, Holstein and Flachs 18 ). In the present study most of the students ate their lunch in their classroom (86 %). In some instances, the teacher was present during the lunch break, eating his or her own lunch meal.

Study design and study population

We used Danish data from the international cross-sectional study ‘Health Behaviour in School-aged Children’ (HBSC)( Reference Currie, Nic and Godeau 38 ). Data collection is conducted every fourth year among students aged 11, 13 and 15 years (in Denmark, equivalent to 5th, 7th and 9th grade, respectively) in a random sample of schools (i.e. cluster sampling). The students completed the self-administered, internationally standardised and anonymous HBSC questionnaire at school( Reference Roberts, Freeman and Samdal 39 ). In 2010 the Danish sample included 137 schools, of which seventy-three agreed to participate. The reason for non-participation was almost always that the school had recently participated in a similar survey and did not want to invest time in yet another study. We do not suspect that this non-participation pattern resulted in selection bias. Within these seventy-three schools, sixty-nine headmasters completed a questionnaire about the school setting, response rate 69/73=94·5 %. The participating schools comprised 5704 students in 302 classes. Of these, 4985 students in 280 participating classes were present on the day of data collection, and 4922 students submitted a satisfactorily answered questionnaire (fifteen did not fill out the questionnaire, thirty-eight did not indicate gender and ten were subjectively evaluated as unserious). The response rate was 86·3 % (4922/5704). The mean ages of the participants in grade 5, 7 and 9 were 11·8 (sd 0·4) years, 13·6 (sd 0·3) years and 15·8 (sd 0·4) years, respectively.

The study was conducted according to the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki. In Denmark there is no formal agency that grants ethical approval of school-based surveys. We received study approval from the school headmaster, the parents’ school board and the students’ council in each of the participating schools. The students received oral and written information that participation was voluntary and anonymous.

Measurements

Dependent variable: lunch frequency

In the literature the definition of lunch consumption varies( Reference Pedersen, Meilstrup and Holstein 4 , Reference Sjöberg, Hallberg and Höglund 8 , Reference Shi, Lien and Kumar 13 , Reference Abudayya, Stigum and Shi 14 , Reference Höglund, Samuelson and Mark 19 ) and terms such as lunch pattern, skipping lunch and regularity of lunch are used across the literature. Based on the inconsistent terminology and definitions applied in the literature, we have chosen to use the term ‘lunch frequency’, which best describes our measure. Furthermore, in the present study, we applied the approach that lunch frequency can still be defined as frequent despite occasionally being skipped.

Lunch frequency was measured by a frequency question on weekdays that is part of the Danish HBSC questionnaire. We dichotomized the variable and defined low lunch frequency as consuming lunch on fewer than four out of five weekdays (Table 1). Sensitivity analyses involving cut-off points defined by two and four weekdays or less, respectively, were conducted. These showed no changes in the directions of association. The lunch frequency item has been validated in a Danish validation study against 24 h recall measures among 11–15-year-olds, demonstrating 84 % agreement and κ=0·54 for the dichotomized variable (TP Pedersen, BE Holstein, B Laursen et al., unpublished results, available upon request). Also, the measure of lunch frequency was included in a larger qualitative validation study of meal habits where the face and content validity of the lunch frequency item were tested among students in three age groups (11-, 13- and 15-year-olds). In total we conducted twenty gender-divided focus group discussions at five schools with two to five students in each group. The objective was to learn about the students’ perceptions and experiences of the measure immediately after they had answered the questionnaire; further, to understand how they understood the concepts breakfast, lunch and evening meal. We found high face validity with regard to lunch as the students found it easy to answer the item and the term lunch was a generally used concept. Only a few students found it difficult to define the term lunch. To clarify the content validity the students were asked about the concept of a proper meal in the middle of the day. Especially the youngest had trouble defining a ‘proper meal’ but they mentioned both healthy and unhealthy foods and good tasting and defined lunch as their packed lunch or something that made them full. Further, it had to be ‘proper food’. The study also revealed that the understanding of a meal and meal norms differs by migration status and family culture (CA Johnson and TP Pedersen, unpublished results, available upon request).

Table 1 Item wording, response keys and categorization used in the analyses

Individual level: sociodemographic variables

We included gender, age group, socio-economic position, migration status and family structure in the analyses. Grade (5th, 7th and 9th) was used as a proxy for age as the age variation within grades in Denmark is small. Socio-economic position was measured by family occupational social class. Most students are able to report their parents’ occupation in a valid way( Reference Lien, Friestad and Klepp 40 ). Students’ responses to items about parent occupation were coded into family social class by the research staff and categorized into high, medium and low family social class. We followed the definitions of social class applied by the Danish National Institute of Social Research, which is almost identical to the UK Registrar General’s classification( Reference Hansen 41 , Reference Galobardes, Shaw and Lawlor 42 ). Migration status was assessed by self-report and students were classified as natives, descendants of immigrants and immigrants based on their responses to items assessing their own and their parents’ birth countries. Students’ family structure was described as traditional family (living with two biological parents), single parent, reconstructed family (living with mother and stepfather or with father and stepmother) and other family types (e.g. foster homes; Table 1).

School level: school characteristics variables

Six school characteristics variables were included: (i) school rules that allow students to leave school during lunch break separately in the three age groups (yes/no); (ii) availability of a canteen (yes/no); (iii) availability of school food stand (yes/no); (iv) length of lunch break (asked separately in the three age groups and categorized as less than 15 min v. more than 15 min); (v) presence of an adult during lunch breaks (asked separately in the three age groups and categorized into never/seldom v. always/most of the time); and (vi) availability of a refrigerator for storage of packed lunch (asked separately in the three age groups and categorized into no (‘no’; ‘yes, in a few classes’) v. yes (‘yes, in all classes’; ‘yes, in some classes’; Table 1).

Statistical analyses

All analyses were conducted using the statistical software package SAS version 9·3 and accounted for the clustering of the data. In the descriptive analysis, proportions and χ 2 tests of significance were used to examine sociodemographic (gender, age group, family social class, migration and family structure) differences in lunch frequency. The mean proportion of students with low lunch frequency was generated for each school. Multilevel logistic regression models were generated to study the associations between low lunch frequency and individual-level and school-level variables. We specified three-level models (students nested within classes nested within schools) using PROC GLIMMIX. We used a four-step analytical strategy. First, a pure random-effect model was used to estimate the variation in low lunch frequency between schools and between school classes within the same school. In the second step, individual-level sociodemographic variables were included to investigate their associations with low lunch frequency and to examine how much of the between-school variance in low lunch frequency was explained by the student composition of schools. In the third step we included the school characteristics variables and controlled for sociodemographic variables. Finally, we tested modification by means of testing for cross-level interaction between the school-level variables and gender and age group. We included interaction terms in the model one at a time. Interaction terms with P<0·1 were explored in detail by examining the joint effect, i.e. the combined effect of two variables( Reference Musert, Jager and Zoccali 43 ). By including the combined effect it is possible to compare the different combinations of the two variables with a common reference category whereby it is possible to identify protective combinations( Reference Vandenbroucke, von Elm and Altman 44 ). The model fit (i.e. dispersion parameter) of all the models ranged between 0·95 and 0·98, which indicate that the model fitted the data. The final full model fit was 0·98.

To examine the variation in low lunch frequency between school and school classes, the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) was calculated for school level and school class level as a measure of the correlation between observations within schools and between classes within a school. The ICC was calculated for low lunch frequency among students within different classes as

![]() $${\mathop{\rm ICC}\nolimits} _{\rm{school}} =\sigma _{3}^{2} /(\sigma _{3}^{2} {\plus}\sigma _{2}^{2} {\plus}\sigma _{1}^{2} )$$

and the ICC for students within the same class and school was calculated as

$${\mathop{\rm ICC}\nolimits} _{\rm{school}} =\sigma _{3}^{2} /(\sigma _{3}^{2} {\plus}\sigma _{2}^{2} {\plus}\sigma _{1}^{2} )$$

and the ICC for students within the same class and school was calculated as

![]() $${\mathop{\rm ICC}\nolimits} _{\rm {school\ {\rm class}}} =(\sigma _{3}^{2} {\plus}\sigma _{2}^{2} )/(\sigma _{3}^{2} {\plus}\sigma _{2}^{2} {\plus}\sigma _{1}^{2} )$$

(

Reference Rabe-Hesketh and Skrondal

45

), where

$${\mathop{\rm ICC}\nolimits} _{\rm {school\ {\rm class}}} =(\sigma _{3}^{2} {\plus}\sigma _{2}^{2} )/(\sigma _{3}^{2} {\plus}\sigma _{2}^{2} {\plus}\sigma _{1}^{2} )$$

(

Reference Rabe-Hesketh and Skrondal

45

), where

![]() $\sigma _{3}^{2} $

is the variance between schools,

$\sigma _{3}^{2} $

is the variance between schools,

![]() $\sigma _{2}^{2} $

is the variance between school classes, and

$\sigma _{2}^{2} $

is the variance between school classes, and

![]() $\sigma _{1}^{2} $

is the variance between individuals and approximated due to use of a logit scale as

$\sigma _{1}^{2} $

is the variance between individuals and approximated due to use of a logit scale as

![]() $\sigma _{1}^{2} =\pi ^{2} /3=3\!\cdot\!29$

(

Reference Merlo, Chaix and Ohlsson

46

).

$\sigma _{1}^{2} =\pi ^{2} /3=3\!\cdot\!29$

(

Reference Merlo, Chaix and Ohlsson

46

).

In the initial analyses, family social class, family structure and migration status were included separately in the analyses. The direction of the estimates for the association between low lunch frequency and family social class, family structure and migration status, respectively, did not change. In the analyses including family social class and family structure, missing values were kept as a separate category. The analyses were run with and without missing as a separate category and the estimates did not change much; in the final analyses missing were kept as a separate category for the two variables to avoid losing observations and power.

Results

Descriptive results

Nearly one-quarter of students had low lunch frequency and this was more common among boys than girls (P=0·011; Table 2). The proportion of students with low lunch frequency increased with age group (P<0·001). Low lunch frequency was more common among students from medium and low family social class (P<0·001), among descendants of immigrants and immigrants (P=0·002), and among students from single parent and reconstructed families (P<0·001).

Table 2 Age-specific distribution of sociodemographic variables and the proportion of students with low lunch frequency, Danish arm of the Health Behaviour in School-Aged Children study 2010

* Low lunch frequency defined as eating lunch on less than four days per week.

At the school level we found that there were no schools that allowed 11-year-olds to leave school during breaks. Among schools with 13- and 15-year-olds, 23 % and 40 %, respectively, permitted leaving the school during lunchtime (Table 3). The proportion of 13-year-olds with low lunch frequency at schools that permitted leaving school was 26·0 %, and this was significantly higher compared with schools not allowing students to leave school (19·3 %; P<0·001). Among 15-year-olds the difference between the two categories of schools was not significant. The proportion of schools that had more than 15 min allocated for lunch breaks was higher in the schools with younger students. The proportion of students with low lunch frequency was similar for both lunch break duration categories and for all three age groups. Likewise, having an adult present at lunch breaks was common among 11-years-olds (88 %) but uncommon among 15-year-olds (28 %). The proportion of 11-year-olds with low lunch frequency at schools that seldom had an adult present was 31·0 %, and this was significantly higher compared with schools where an adult was present during lunch breaks (19·5 %; P<0·001). We found the same pattern among the 13- and 15-year-olds although the differences were not significant among the 15-year-olds. Access to a refrigerator in class was also most common among the schools with 11-year-olds (73·9 %) and less common in schools with older students. The proportion of students with low lunch frequency did not differ significantly between schools with and without refrigerators available. A school food stand was available in more than half of the schools, while a canteen was not that common (11·6 %). The proportion of students with low lunch frequency did not differ significantly between schools with and without a school food stand and canteen available.

Table 3 Age-specific school characteristics variables (n and %) and proportion with low lunch frequency (mean and 95 % CI), Danish arm of the Health Behaviour in School-Aged Children study 2010

The variable ‘availability of school food stand/canteen (yes/no)’ was not asked age-specific but for the entire school and the distribution was as follows. Canteen: no, n 60 (87·0 %); yes, n 8 (11·6 %); missing, n 1 (1·5 %); mean proportion with low lunch frequency: no, 20·3 (95 % CI 17·9, 22·7) %; yes, 27·6 (95 % CI 20·4, 34·8) %; missing, 0·0 %. School food stand: no, n 28 (40·6 %); yes, n 40 (58·0 %); missing, n 1 (1·5 %); mean proportion with low lunch frequency: no, 20·2 (95 % CI 16·4, 24·0) %; yes, 21·8 (95 % CI 18·8, 24·8) %; missing, 0·0 %.

Multilevel analyses

In the initial random-effect model the between-school variance in low lunch frequency was small (ICCschool=1·0 %), whereas a larger school class-level variance in low lunch frequency was identified (ICCschool class=5·7 %). Inclusion of individual-level sociodemographic factors showed that most of the class-level variance in low lunch frequency was due to individual-level variables, i.e. the composition of students in the classes (ICCschool class=3·1 %). In the full model, which also included the school-level variables, the calculated ICC values were small (ICCschool=0·4 %, ICCschool class=2·1 %; Table 4).

Table 4 Sociodemographic and school effects on low lunch frequency: results from multilevel logistic regression analyses, Danish arm of the Health Behaviour in School-Aged Children study 2010

ICC, intraclass correlation coefficient.

In the sociodemographic model, all sociodemographic variables were associated with low lunch frequency (Table 4). In the full model, there were two school-level variables with significant associations with low lunch frequency. Students attending schools with a canteen were significantly more likely to have low lunch frequency. Likewise, limited adult presence during lunch was significantly associated with low lunch frequency.

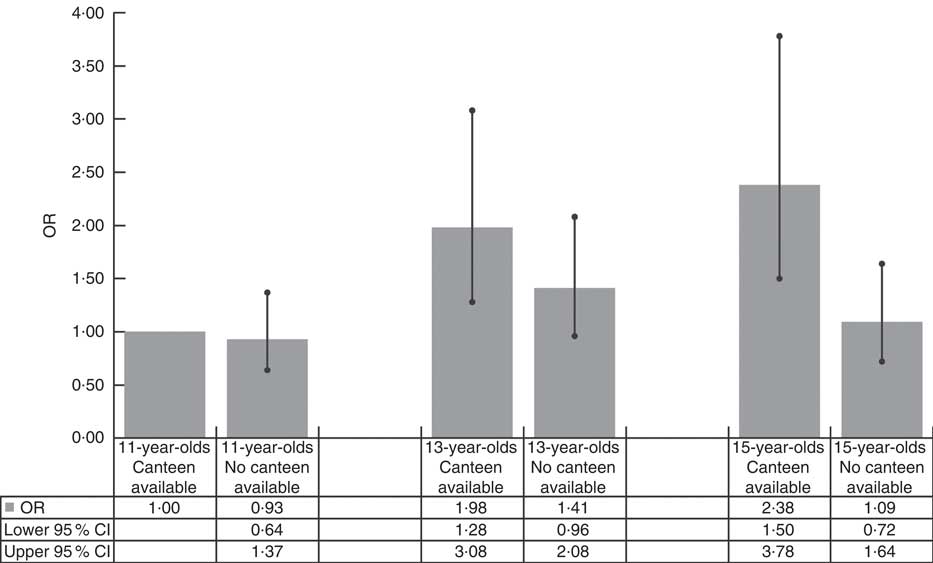

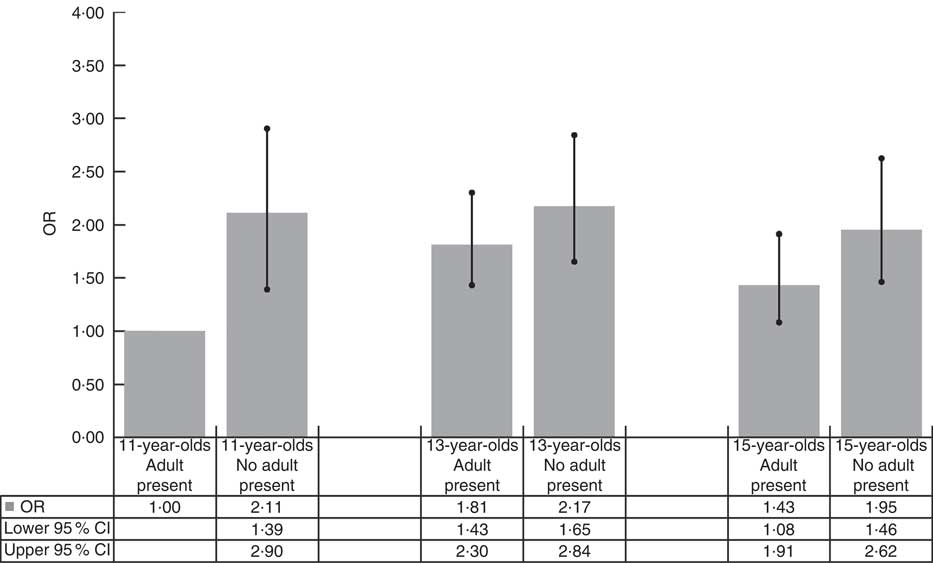

Finally, there were significant cross-level interactions between availability of canteen and age group (P=0·019) and an adult present and age group (P=0·089; Table 4). Figures 1 and 2 illustrate the significant interaction terms by analyses with a joint reference category. An increased risk of low lunch frequency was observed among both 13- and 15-year-olds in schools with canteens, whereas there were no differences in lunch frequency for 11-year-olds (Fig. 1). In contrast, the presence of an adult appeared to act as a protective factor for low lunch frequency among 11-year-olds, but not among the older students (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1 Odds ratios (and 95 % confidence intervals, represented by vertical bars) for low lunch frequency by combinations of age group and availability of a canteen, adjusted for sociodemographic variables, Danish arm of the Health Behaviour in School-Aged Children study 2010

Fig. 2 Odds ratios (and 95 % confidence intervals, represented by vertical bars) for low lunch frequency by combinations of age group and adult present, adjusted for sociodemographic variables, Danish arm of the Health Behaviour in School-Aged Children study 2010

Discussion

The present study has four key findings. First, we found little variation in low lunch frequency between schools and between classes within schools. Second, lunch frequency was associated with adolescents’ sociodemographic background. We found higher odds for low lunch frequency among boys, 13- and 15-year-olds, medium and low family social class, descendants of immigrants, and single parent and reconstructed families. Third, the presence of an adult during lunch breaks appeared to promote frequent lunch consumption while the opposite was observed for availability of a canteen. Fourth, these associations appeared to vary between older and younger students.

In the present study we found that most of the variation in lunch consumption was attributable to variables at the individual level. We have not been able to identify studies that have investigated school- and class-level variation in lunch consumption. With regard to low breakfast frequency, one study found a class-level variation among Danish 14–16-year-olds (school class ICC=3·2 %)( Reference Johansen, Rasmussen and Madsen 47 ). However, since breakfast is commonly consumed at home and lunch is commonly consumed at school, it is difficult to compare the results.

Our finding with regard to boys having low lunch frequency more often than girls is consistent with findings from Gaza( Reference Abudayya, Stigum and Shi 14 ), but not with previous studies in Denmark or Sweden( Reference Pedersen, Meilstrup and Holstein 4 , Reference Höglund, Samuelson and Mark 19 ). Our finding that lunch frequency decreases with age is consistent with previous studies in Denmark( Reference Pedersen, Meilstrup and Holstein 4 ), but not with the study from Gaza( Reference Abudayya, Stigum and Shi 14 ). Our results showed that low socio-economic position was associated with low lunch frequency and this finding is consistent with one previous study( Reference Abudayya, Stigum and Shi 14 ), but other studies have not identified such social patterns( Reference Sjöberg, Hallberg and Höglund 8 , Reference Shi, Lien and Kumar 13 , Reference Höglund, Samuelson and Mark 19 ). Our finding that descendants of immigrants more often have low lunch frequency than the majority population is not comparable with any existing studies, since no study to our knowledge has examined lunch frequency among descendants of immigrants. Sjöberg et al. found no ethnic differences (one Nordic parent v. others) in lunch consumption among Swedish 15–16-year-olds( Reference Sjöberg, Hallberg and Höglund 8 ). Our results showed that adolescents from single parent and reconstructed families had higher odds of low lunch frequency compared with adolescents from traditional families. We have not identified any studies investigating this association, but similar findings exist for low breakfast frequency( Reference Vereecken, Dupuy and Rasmussen 20 – Reference Levin, Kirby and Currie 23 ). The clear associations with several sociodemographic factors and adolescents’ lunch frequency indicate that adolescents’ living conditions may influence their frequency of lunch.

To our knowledge, the present study is one of the first to investigate how school characteristics are associated with students’ lunch frequency. The presence of an adult, which is likely to be a teacher or another pedagogical employee at the school during lunch break, appears to promote frequent lunch consumption. However, the cross-level interactions and joint effect analyses suggest that having an adult present at lunchtime may be most important for lunch frequency among younger students. Young and Fors found that the presence of an adult at home promoted a healthy lunch( Reference Young and Fors 30 ), which corresponds to our finding. In line with Bandura’s social learning theory( Reference Bandura 48 ), a common feature for the two different settings may be that adolescents learn behaviour by observing others, for instance an adult eating his or her own lunch during the lunch break. The presence of a teacher may assure a calm atmosphere where the adolescents can eat in peace but we have no data to support such an interpretation. Our finding that availability of a canteen promoted low lunch frequency was unexpected. Cross-level interactions and joint effect analyses suggested that the effect of school canteens on lunch consumption may be most detrimental for older (13–15-year-olds) students. However, our measure of availability did not account for other factors that may influence lunch consumption, such as supply, price, variety and quality of the food offered in canteen. Our findings may reflect that the choice of food in the canteen is too limited in which case some students might replace their lunch with snacks from the canteen. They may not consider such snacks to constitute a meal and thereby they report having skipped lunch( Reference Park, Sappenfield and Huang 49 ). The finding might also reflect that parents of students at schools with no canteen may be more aware of providing a packed lunch from home. Consistent with our findings, Krølner et al. found that availability of fruit and vegetables at schools did not promote student fruit and vegetable consumption( Reference Krølner, Due and Rasmussen 26 ). School policies such as allowing students to leave school during school hours, total time available for lunch and availability of refrigerators in classrooms did not show any significant associations with lunch frequency. To our knowledge, these aspects of the school environment have not been previously examined with regard to lunch consumption.

Comparing conclusions across studies is difficult due to differences in country settings. This is also the case for the present study, where meal culture and norms may differ significantly. Such cultural differences may contribute in part to the described differences between the findings of the present study and previous findings.

Strengths and limitations

The main strengths of the present study are the inclusion of a large, nationally representative sample of adolescents with data from two sources: the school headmaster and the students. The response rates within the participating schools were high at both the school and student level. Initial pilot studies suggested that the measurement of lunch frequency was valid.

There are a few limitations to consider, though, in interpreting our findings. The response rate in the participating schools was high but the risk of selection bias cannot be neglected. If the students who did not answer the questionnaire are more likely to come from low-resource families and also more likely to skip lunch, then we have underestimated the associations between the sociodemographic factors and lunch frequency.

We suspect that use of information from the school headmaster may result in some information bias as they may not be informed in details, for example about the presence of an adult during lunch breaks. Teachers may provide an alternative information source for future collection of school- and school class-level data.

There may have been other individual-level factors related to adolescent lunch consumption, but they were beyond the scope of the current study. Specifically, low lunch frequency and meal skipping have been associated with overweight( Reference Toschke, Kuchenhoff and Koletzko 1 , Reference Koletzko and Toschke 6 ), dieting( Reference Neumark-Sztainer and Story 50 ), snacking( Reference Savige, Macfarlane and Ball 51 ), irregular breakfast consumption( Reference Sjöberg, Hallberg and Höglund 8 , Reference Tin, Ho and Mak 52 ) and media use( Reference Custers and Van den Bulck 53 , Reference Van den Bulck and Eggermont 54 ), and also family-related measures e.g. parents’ lunch habits and the family values related to eating could be considered( Reference Pearson, Williams and Crawford 55 , Reference Burgess-Champoux, Larson and Neumark-Sztainer 56 ).

Implications

From a public health perspective it is important to focus on adolescents’ lunch frequency as meal frequencies may influence the health and well-being of adolescents( Reference Toschke, Kuchenhoff and Koletzko 1 – Reference Koletzko and Toschke 6 , Reference Sjöberg, Hallberg and Höglund 8 , 11 ). Our results highlight the importance of considering students’ sociodemographic circumstances when promoting lunch frequency, e.g. free lunch for students at school. Provision of lunch meals at school has been shown to improve the quality of students’ dietary intake( Reference Raulio, Roos and Prättälä 28 , Reference Condon, Crepinsek and Fox 29 ). The current study is based on natural variations in school-level characteristics and controlled interventions introducing more variation are needed to identify the school characteristics most relevant for promoting frequent lunch consumption among adolescents. Although difficult to manage in practice, the present study indicates that the influence of school-level characteristics on adolescents’ lunch frequency depends on individual-level sociodemographic factors.

The present study identifies consistent associations between sociodemographic factors and adolescent lunch frequency. To understand the mechanisms underlying these observations, additional qualitative and quantitative studies are needed. Further, there is a need for more studies examining the predictors and consequences of low lunch frequency in longitudinal designs. These should combine information on both lunch frequency and quality of the lunch eaten. Future research should include more refined variables to explain more of the association between the school setting and low lunch frequency. Further, the measure of availability of lunch should be developed to include food offered, quality and price of food. Other school setting factors that might influence adolescents’ lunch frequency could be characteristics of the eating environment at the school. A nice and pleasant eating environment may encourage adolescents to eat lunch. Also it would be interesting to include explanatory factors at the school class level. Denmark is an obvious setting to study school class influence since students generally attend the same school class during their entire school period. Relevant class-level variables would be physical amenities and direct measures of perceptions of lunch consumption in the class.

The ecological model also includes the social setting and we propose that future research adopts this model in order to provide a better understanding of adolescents’ lunch habits. In the present study we have no measure of the social setting, e.g. whether the participants’ friends and parents eat lunch. Other studies have found that meal skipping is associated with parental and friends’ meal skipping and that adolescents who skip breakfast are more friend-oriented than adult-oriented( Reference Pearson, Biddle and Gorely 21 , Reference Johansen, Rasmussen and Madsen 47 , Reference Pearson, Williams and Crawford 55 , Reference Bruening, Eisenberg and MacLehose 57 ). In future studies it would be interesting to include friend- and family-related measures and to explore if the school setting modifies the influence of the family setting.

Conclusion

The variation in adolescent lunch frequency is mainly attributable to factors at the individual level. Low lunch frequency is more common among boys, students from medium and low family social class, descendants of immigrants, students living in single parent or reconstructed families, and among the older students. In the school setting, the presence of an adult during lunch breaks promotes frequent lunch consumption while availability of a canteen does not promote frequent lunch consumption. The effect of the school setting factors varies in different age groups.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: The authors thank the Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC) for use of data. The international coordinator is Professor Candace Currie from the University of St Andrews and the international data bank manager is Professor Oddrun Samdal from the University of Bergen. Danish Principal Investigators are Professor Pernille Due and Associated Professor Mette Rasmussen from the National Institute of Public Health. Financial support: This work was supported by the Nordea Foundation (grant number 02-2011-0122). The Nordea Foundation had no role in the design, analysis or writing of this article. Conflict of interest: None. Authorship: T.P.P., B.E.H. and M.R. contributed to the planning of research questions and analytical strategy. Data analyses were conducted by T.P.P. T.P.P. drafted the manuscript with critical input and interpretations from B.E.H., R.K., A.K.E., T.S.J., A.K.A., J.U., S.A.M., D.N.-S. and M.R. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. Ethics of human subject participation: This study was conducted according to the principles of informed consent, with oral and written information for the participants that participation was voluntary and completely anonymous. It was conducted according to the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki Ethical and approval was not required. In Denmark, there is no agency for approval of non-invasive studies such as questionnaire-based studies in the general population. Because there is no such agency, we asked for approval by the school headmasters and school boards.