The importance of nutrition in health and well-being is strongly recognised across the world(1). People in almost every region of the world could benefit from rebalancing their diets to eat optimal amounts of various foods and nutrients, according to the Global Burden of Disease study, where trends in consumption of fifteen dietary factors were tracked from 1990 to 2017 in 195 countries(Reference Afshin, Sur and Fay2,Reference Forouhi and Unwin3) . Globally, one in five deaths is associated with poor diet, which contributes to a number of chronic diseases(Reference Afshin, Sur and Fay2). Poor diet is responsible for more deaths than any other risk factor(Reference Afshin, Sur and Fay2). Leading dietary risk factors are high sodium intake and low intake of healthy foods, such as whole grains, fruits, nuts and seeds, and vegetables(Reference Afshin, Sur and Fay2). It is now recognised that dietary modification can be more effective than medication for the management of many chronic diseases(Reference Knowler, Barrett-Connor and Fowler4) and has the potential to significantly improve biomarkers associated with chronic disease(Reference Coppell, Kataoka and Williams5). Small changes in weight and biomarkers at a population level can have a large impact on the burden of disease of populations(6). It is therefore not surprising that a healthy diet is a highly recommended feature of chronic disease prevention and management(7,8) .

An important strategy to support healthy eating in populations is to advocate for healthy eating through health-care services(Reference Green9). Primary care has been identified as an ideal setting to help patients have a healthy diet(10,Reference Harris, Fanaian and Jayasinghe11) . Primary-care physicians (PCP) are ideally placed to provide nutrition care to patients as they represent the initial point of contact within the health-care system(12) and their nutrition care is held in high regard by patients(Reference Ball, Johnson and Desbrow13). Within consultations, nutrition care is defined as any practice that aims to improve the dietary intake of a patient to improve health outcomes and can include nutrition assessment, nutrition advice or nutrition counselling(Reference Ball, Hughes and Leveritt14,Reference Cash, Desbrow and Leveritt15) . As a generalist doctor, PCP have a gatekeeper role for nutrition that requires confidence in nutrition care, including appropriate nutrition knowledge, skills and attitudes to counsel patients about their diet and recognise when there is a need to refer on to other health professionals, such as dietitians, for more specialised nutrition care(16).

There have been enduring claims since the 1980s that PCP provide inadequate nutrition care to patients(Reference Levine, Wigren and Chapman17–Reference Buttriss21), with minimal clear gains over recent times. It is currently estimated that nutrition care occurs in less than 7 % of consultations(Reference Britt, Miller and Henderson22) and less than 37 % of people with a poor diet remember ever discussing nutrition in a consultation with a PCP(Reference Harris, Fanaian and Jayasinghe11). Several barriers that prevent PCP from providing nutrition care are well recognised, including lack of nutrition education(Reference Levine, Wigren and Chapman17,Reference Kushner18,Reference Hiddink, Hautvast and Van Woerkum23) , subsequent perceived lack of nutrition knowledge, low confidence and self-efficacy in nutrition(Reference Ball, Hughes and Leveritt14,Reference Levine, Wigren and Chapman17,Reference Kushner18,Reference Hiddink, Hautvast and Van Woerkum23,Reference Hopper and Barker24) and a perceived lack of time in consultations(Reference Ball, Hughes and Leveritt14,Reference Kushner18,Reference Hiddink, Hautvast and Van Woerkum23,Reference Wynn, Trudeau and Taunton25) . A new way of examining this problem is needed to overcome these barriers and better inform strategies for supporting PCP to provide nutrition care and address the research gap in this area.

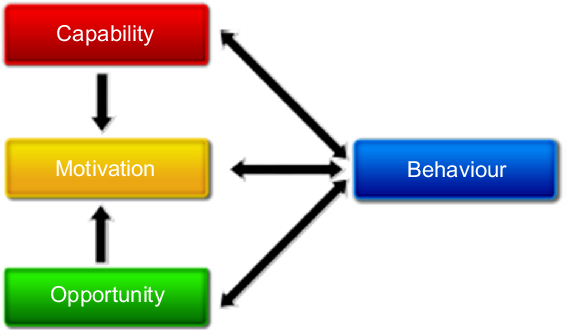

Guidelines for interventions that aim to modify how health professionals provide care include utilising theories that attempt to explain their behaviours(Reference Craig, Dieppe and Macintyre26). One such theory is the COM-B model(Reference Michie, van Stralen and West27), which proposes that the target behaviour (to provide nutrition care) is influenced by one’s capability to perform the task (knowledge and skills), motivation to perform the task and opportunity to perform the task, including factors that lie outside the control of the individual (see Fig. 1)(Reference Michie, van Stralen and West27). This is an important model for population health as it can be applied at the level of health professionals and therefore influence their actions with patients and subsequent health outcomes. Better understanding of the problem using the lens of this theory has the potential to inform novel strategies to support PCP to provide nutrition care. Higher rates of nutrition care have the potential to make significant positive impacts at a population health level(Reference Ball, Lee and Ambrosini28). The present integrative review critically synthesises literature that has investigated nutrition care provided by PCP. It uses the COM-B framework as a lens for interpreting the current status of the problem and provides new insights into how PCP can be supported to provide nutrition care that meets the needs of their patients and the broader population.

Fig. 1 The COM-B system – a framework for understanding the behaviour of health professionals, including primary-care physicians. (From Michie et al.(Reference Michie, van Stralen and West27))

Methods

Overview

An integrative review synthesises a diverse range of qualitative and quantitative literature to provide a comprehensive understanding of a phenomenon of interest(Reference Whittemore and Knafl29). While the diversity and inclusivity of integrative reviews allow for a rich understanding of the topic, data analysis is made more complex(Reference Whittemore and Knafl29,Reference Whittemore30) . Therefore, to ensure a rigorous review process in the present integrative review, the five steps outlined by review guidelines were utilised(Reference Whittemore and Knafl29): problem identification, literature search, data evaluation, data analysis and presentation.

Problem and inclusion criteria

The present integrative review examined the enduring problem of inadequate nutrition care provided by PCP. From this problem, the review questions were developed using the SPIDER tool (Sample, Phenomenon of interest, Design, Evaluation and Research type)(Reference Cooke, Smith and Booth31). Studies and papers were included if: (i) the study involved PCP or gathered data on PCP, including their international equivalents such as general practitioners, family doctors and family physicians; (ii) the study examined any aspect of PCP nutrition knowledge, skills and/or confidence in providing nutrition care; and (iii) the study was empirical, full text, in English and published between 2012 and 2018. This time period was chosen as the most recent synthesis of literature came from the 2012 International Heelsum workshop(Reference van Weel, Roberts and De Maeseneer32). The International Heelsum Collaboration on Nutrition in Primary Care was a group of medical, behavioural, communication, epidemiological and nutrition experts who met six times in conference workshop format between the mid-1990s and 2012. The overarching aim of the Heelsum workshops was to advocate for research and advancements that assist general practitioners to appropriately incorporate nutrition concepts during consultations with patients(Reference van Weel, Hiddink and Truswell33). Studies that focused solely on medical students and their nutrition education were excluded in the present review and will be published elsewhere.

Literature search

A systematic literature search was conducted between May and July 2018. The literature search included computerised searches, ancestry searching and journal hand-searching to ensure all eligible studies were included(Reference Whittemore and Knafl29). A health librarian assisted with the computer-based search of MEDLINE, PubMed, Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) and Scopus. Medical subject headings were used in the execution of PubMed and MEDLINE database searches. Search terms related to PCP included ‘primary care physician’, or ‘family doctor’, ‘general practitioner’ or ‘family physician’. Search terms for the topic of interest included ‘nutrition’, ‘knowledge’, ‘competence’, ‘skills’, ‘confidence’, ‘nutrition care’, ‘nutrition advice’ or ‘nutrition education’. Google Scholar was used to obtain additional articles identified by journal hand-searching. All databases’ search results were imported into EndNote prior to screening.

Data extraction and evaluation

One investigator (J.C.) screened the title and abstract of all 805 studies initially identified through the search using the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Studies that appeared to meet the inclusion criteria based on their title and abstract were retrieved for further review. A total of thirty-five studies were included from the initial screen. Two investigators (J.C. and L.B.) independently assessed the full texts using the inclusion and exclusion criteria to establish a final number of included studies. Any discrepancies were discussed prior to excluding studies and a third reviewer (G.J.H.) was used if consensus was not reached following a short discussion. Studies excluded were coded based on the exclusion criteria. Data were extracted by J.C. using a table developed by the research team. Data extracted included author, year, country, aim, research design, sample, participants, and key or relevant findings. To ensure accuracy, one investigator (L.B.) cross-checked the extracted data using the full text of each included study.

Critical appraisal of the data was conducted by two independent investigators (J.C. and L.B.) using the Mixed Methods Appraisal tool (MMAT), version 2011(Reference Pace, Pluye and Bartlett34). The MMAT allows for simultaneous evaluation of all empirical literature: qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods studies(Reference Pluye, Gagnon and Griffiths35), making it appropriate for an integrative review. The tool involves four questions which are answered as ‘yes’, ‘no’ or ‘unclear’, resulting in an overall score ranging from 0 to 4. This tool has been shown to be efficient (15 min per study), user-friendly and has high intraclass correlation(Reference Pace, Pluye and Bartlett34). Agreement was reached on nearly all (>90 %) of the appraisal items. Where scores differed, discrepancies were resolved through discussion.

Data analysis

The present integrative review included both qualitative and quantitative studies, which were analysed thematically using meta-synthesis, an integrative interpretation of results to offer a novel finding(Reference Michie, van Stralen and West27,Reference Whittemore30) .

Results

Descriptive findings

The study selection process is described in Fig. 2. Out of 805 possible studies, sixteen met the inclusion criteria and were included in the review (Table 1). The studies were mostly descriptive surveys (n 12)(Reference Khandelwal, Zemore and Hemmerling36–Reference Bleich, Bennett and Gudzune47), as well as two descriptive designs that used video observations(Reference Laidlaw, McHale and Locke48,Reference Pollak, Coffman and Alexander49) , one qualitative focus group study(Reference Crowley, Ball and McGill50) and one intervention study(Reference Fitzpatrick, Dickins and Avery51). Participant numbers for all studies ranged from three to 4074; most were between forty-seven and 1136 with the exception of one larger study(Reference Gorig, Mayer and Bock43). All studies were published between the years 2012 and 2018. Studies were mostly conducted in the USA (n 6), Europe (n 4), the UK (n 1), the Middle East (n 1), Australia (n 2) and New Zealand (n 2). Of the four European studies, one was conducted in the Netherlands, one in Germany, one in Denmark and one in Croatia. The study from the Middle East was from Lebanon.

Fig. 2 Overview of study selection for the present integrative review examining literature on nutrition care provided by primary-care physicians from 2012 to 2018

Table 1 Description of studies (n 16) included in the present integrative review examining literature on nutrition care provided by primary-care physicians from 2012 to 2018

IM, internal medicine; PCP, primary-care physician; c-RT, cluster randomised trial; GPR, general practice registrar; FM, family medicine; OB/GYN, obstetrics and gynaecology; MI, motivational interviewing.

† Quality score ranges from meeting none of the four criteria (0) to meeting all criteria (****).

The methodological quality of the studies ranged from 0 (lowest quality) to 4 (highest quality) out of 4, with many studies scoring 2(Reference Pluye, Gagnon and Griffiths35). Three studies scored 0 for methodological quality(Reference Hseiki, Osman and El-Jarrah38,Reference Nowson and O’Connell41,Reference Pollak, Coffman and Alexander49) . The most common limitations of the studies were that the measurement tool did not have established validity and the response rate was low, increasing the likely presence of response bias.

Meta-synthesis

Three themes were developed in line with the COM-B framework: (i) PCP capability to provide nutrition care; (ii) PCP motivation to provide nutrition care; and (iii) PCP opportunity to provide nutrition care.

Primary-care physicians’ capability to provide nutrition care

All of the studies were based on the premise that it is essential for PCP to be capable of providing nutrition care in order to meet the needs of patients and the population. PCP capability to provide nutrition care was specifically referred to in some studies as a prerequisite for competent nutrition care(Reference Smith, Seeholzer and Gullett42,Reference Crowley, Ball and McGill50) , and strongly connected with motivation and opportunity to provide nutrition care(Reference Gorig, Mayer and Bock43,Reference Bleich, Bennett and Gudzune47) . PCP in two studies stated that nutrition capability should encompass the biological, social, economic, cultural and spiritual aspects of food and nutrition due to their relevance and importance to patients(Reference Bleich, Bennett and Gudzune47,Reference Crowley, Ball and McGill50) .

No consensus method exists for assessing PCP capability (including knowledge or skills). It is therefore not surprising that no study objectively assessed PCP knowledge. Rather, studies chose to investigate PCP perceptions of their own nutrition capability (usually framed as ‘knowledge’ or ‘skills’). The PCP in most of these studies reported their capability as inadequate(Reference Hseiki, Osman and El-Jarrah38,Reference Crowley, Ball and Wall40,Reference Bleich, Bennett and Gudzune47,Reference Pollak, Coffman and Alexander49) . For example, one study reported a mean counselling knowledge score on a 0–100 scale of 50·8 (sd 15·6)(Reference Pollak, Coffman and Alexander49). However, one study reported good-to-very-good nutrition knowledge(Reference Hseiki, Osman and El-Jarrah38). The consistent explanation given for PCP perceived lack of nutrition capability was inadequate nutrition education received during medical training(Reference Khandelwal, Zemore and Hemmerling36,Reference Hseiki, Osman and El-Jarrah38–Reference Crowley, Ball and Wall40) . Low levels of nutrition capability meant that doctors felt they were unable to advise patients on the essential role of nutrition in the cause, prevention and treatment of disease in an evidence-based manner(Reference Hseiki, Osman and El-Jarrah38,Reference Nowson and O’Connell41) .

PCP with greater self-efficacy in nutrition were more likely to report providing nutrition care(Reference van Dillen, Hiddink and Woerkum46). Furthermore, PCP perceptions of their nutrition capability were higher in more experienced PCP(Reference Bleich, Bennett and Gudzune47,Reference Pollak, Coffman and Alexander49) but did not seem to be affected by age or gender(Reference Hseiki, Osman and El-Jarrah38). Having a personal interest in nutrition(Reference Dumic, Miskulin and Licanin37,Reference Hseiki, Osman and El-Jarrah38,Reference Gorig, Mayer and Bock43) and having healthy personal eating habits(Reference Hung, Keenan and Fang45) also appeared to influence PCP perception of their nutrition capability. Nutrition topics currently in the media reportedly provided a ready means of increasing nutrition knowledge(Reference Hseiki, Osman and El-Jarrah38) as did association with other health-care professionals, such as dietitians(Reference Crowley, Ball and McGill50). Several studies demonstrated that PCP requested further training in nutrition to incorporate and reinforce current nutrition recommendations into practice(Reference Crowley, O’Connell and Kavka39,Reference Smith, Seeholzer and Gullett42,Reference Hung, Keenan and Fang45,Reference Bleich, Bennett and Gudzune47) . Many PCP stated they wished they had received more nutrition education while at medical school(Reference Bleich, Bennett and Gudzune47), during PCP training(Reference Bleich, Bennett and Gudzune47) and in continuing education sessions(Reference Crowley, O’Connell and Kavka39) to address their self-perceived low nutrition capability(Reference Crowley, O’Connell and Kavka39,Reference Smith, Seeholzer and Gullett42,Reference Hung, Keenan and Fang45,Reference Bleich, Bennett and Gudzune47) . One study rejected the suggestion of further training in nutrition care which appeared to be influenced by a low motivation for this aspect of care(Reference Crowley, Ball and McGill50).

Primary-care physicians’ motivation to provide nutrition care

In three studies, PCP expressed a genuine interest in nutrition and appeared motivated to provide nutrition care(Reference Dumic, Miskulin and Licanin37,Reference Crowley, O’Connell and Kavka39,Reference Crowley, Ball and Wall40) . However, some participants in other studies demonstrated low motivation to provide nutrition care(Reference Khandelwal, Zemore and Hemmerling36,Reference Crowley, Ball and McGill50) . Poor motivation to provide nutrition care seemed to be more pronounced in participants who had graduated from medical school several years ago compared with new graduates(Reference Crowley, Ball and Wall40,Reference Bleich, Bennett and Gudzune47) and participants who felt they had previously been unsuccessful in supporting patients to improve their diet(Reference Gorig, Mayer and Bock43,Reference Bleich, Bennett and Gudzune47) . PCP clearly showed low motivation to provide nutrition care when they felt they lacked nutrition capability(Reference Gorig, Mayer and Bock43,Reference Bleich, Bennett and Gudzune47) . However, additional training in topics such as motivational interviewing seemed to increase motivation to provide nutrition care(Reference Pollak, Coffman and Alexander49). In two studies, the authors interpreted PCP low motivation for nutrition care as a key factor contributing to the evidence–practice gap(Reference Hseiki, Osman and El-Jarrah38,Reference Crowley, O’Connell and Kavka39) .

Factors that influenced PCP motivation for nutrition care were explored in several studies. PCP with a personal interest in nutrition and its effects on health reported drawing on this motivation when including nutrition care in consultations(Reference Dumic, Miskulin and Licanin37). Similarly, PCP with healthy lifestyle habits reported providing nutrition care regularly in practice(Reference van Dillen, Hiddink and Woerkum46,Reference Fitzpatrick, Dickins and Avery51) . For some PCP, their motivation was influenced by medical educators who acted as role models for them when they were students(Reference Khandelwal, Zemore and Hemmerling36). One study examined the motivation for nutrition care among family medicine residents as well as internal medicine residents and obstetrics and gynaecology residents(Reference Smith, Seeholzer and Gullett42). Family medicine residents demonstrated greater motivation and perceived norms to provide nutrition care compared with internal medicine and obstetrics and gynaecology residents(Reference Smith, Seeholzer and Gullett42).

The priority that PCP placed on nutrition care was investiged in some studies as a proxy for motivation. One study used video observations of PCP providing nutrition care to overweight patients and found that PCP spent more time discussing nutrition with female patients and heavier patients(Reference Pollak, Coffman and Alexander49). That study contrasted with another that examined consultations with adults and found that PCP prioritised nutrition care for male patients over female patients(Reference Rohde, Hessner and Lous44). In the same study, younger female PCP (≤48 years) and older male PCP (>57 years) reported it was more important to recommend lipid-lowering medication to male rather than female overweight patients (P = 0·01)(Reference Rohde, Hessner and Lous44). In contrast, younger male PCP (≤56 years) reported it was more important to recommend weight loss for overweight males compared with females (71·4 v. 54·8 %, P = 0·004)(Reference Rohde, Hessner and Lous44). Collectively, these studies highlight that PCP motivation for nutrition care can differ based on characteristics of patients as well as their own characteristics.

Primary-care physicians’ opportunity to provide nutrition care

PCP opportunity to provide nutrition care encompassed all factors identified in the studies that were seen to be beyond the control of PCP. Several studies identified that the health-care system in the country of study did not provide payment to PCP for nutrition care(Reference Hseiki, Osman and El-Jarrah38,Reference Gorig, Mayer and Bock43,Reference Fitzpatrick, Dickins and Avery51) . Understandably, the lack of financial recognition for nutrition care often meant that PCP felt there was insufficient time to include this practice in consultations(Reference Gorig, Mayer and Bock43,Reference Crowley, Ball and McGill50) . One study acknowledged that PCP were more likely to provide nutrition care to patients with private medical insurance, which may be related to the ability to be remunerated for this practice(Reference Gorig, Mayer and Bock43). Two studies identified practice-based changes that could facilitate opportunity to provide nutrition care, including having access to scales that accommodate obese patients and having prompts in the electronic patient-management system to record weight and give recommendations for nutrition and physical activity(Reference Bleich, Bennett and Gudzune47,Reference Fitzpatrick, Dickins and Avery51) .

Studies often reported that PCP could have greater opportunity to provide nutrition care if there were changes at governmental and professional organisational levels. Suggested changes at government level involved creating health policies that required additional primary prevention and health promotion initiatives(Reference Dumic, Miskulin and Licanin37). Similarly, suggested changes at a professional level included having mandatory nutrition training for PCP(Reference Dumic, Miskulin and Licanin37,Reference Bleich, Bennett and Gudzune47) . An example provided of a professional-level change was the introduction of a nutrition syllabus into the Royal New Zealand College of General Practitioners’ training programme in 2012(12). Additionally, one study suggested that greater access to professional development opportunities was required in order for PCP to develop their capability in nutrition care(Reference Crowley, O’Connell and Kavka39).

Discussion

We have used the COM-B framework as a lens for interpreting the problem of PCP inadequate provision of nutrition care to patients. The analysis has added insights to our understanding of a fundamental problem that is preventing health-care services from supporting healthy eating in populations. The COM-B model(Reference Michie, van Stralen and West27) proposes that PCP behaviour in providing nutrition care is predominantly influenced by three interrelated factors: capability, motivation and opportunity (see Fig. 1). Ideally, strategies to address the problem need to impact all three areas of the COM-B model simultaneously. Therefore, we discuss three issues: (i) increasing PCP capability to provide nutrition care; (ii) increasing PCP motivation to provide nutrition care; and (iii) increasing PCP opportunity to provide nutrition care.

Increasing primary-care physicians’ capability to provide nutrition care

Most studies reported that PCP have inadequate capability to provide nutrition care to patients(Reference Hseiki, Osman and El-Jarrah38,Reference Crowley, Ball and Wall40,Reference Bleich, Bennett and Gudzune47,Reference Pollak, Coffman and Alexander49) because they have not had enough nutrition education during medical training(Reference Khandelwal, Zemore and Hemmerling36,Reference Hseiki, Osman and El-Jarrah38–Reference Crowley, Ball and Wall40) and have only experienced limited opportunities for continuing professional development(Reference Bleich, Bennett and Gudzune47,Reference Pollak, Coffman and Alexander49) . These findings concur with earlier studies that describe a lack of nutrition education during medical training(Reference Levine, Wigren and Chapman17,Reference Kushner18,Reference Hiddink, Hautvast and Van Woerkum23) and postgraduate training(Reference Vetter, Herring and Sood52,Reference Jay, Gillespie and Tavinder53) and poor recognition of the role of PCP in improving the health of populations(Reference Truswell54). The need to include education in public health and the environmental determinants of well-being, such as diet and lifestyle, as core elements in medical practice for graduates to deal with these fundamental elements of clinical practice and public health in medical training has previously been recognised(55) and reiterated in subsequent versions(56). Attempts to improve this situation have included: a physician nutrition specialist providing effective nutrition education within a residency programme(Reference Lazarus, Weinsier and Boker57); brief counselling, tailored messages and strategies(Reference Glanz59); the use of the 5 A’s model for stage-based counselling, cooking classes, demonstration kitchens, supermarket tours, computer-based automated telephone counselling and follow-up(Reference Glanz59); nutrition modules for general practice vocational training(Reference Maiburg, Hiddink and van’t Hof60); and a minimal intervention strategy to address overweight and obesity in adult primary-care patients(Reference Fransen, Hiddink and Koelen61). The Heelsum workshops addressed topics such as nutritional attitudes and practices of PCP(Reference Truswell54), effective nutrition interactions between family doctors and patients(Reference Truswell62,Reference Truswell63) , nutritional guidance of family doctors(Reference Truswell, Hiddink and Blom64,Reference Truswell65) , empowering family doctors and patients in nutrition communication(Reference Truswell, Hiddink and van Binsbergen66,Reference Truswell67) , creating supportive environments for nutrition guidance(Reference Truswell, Hiddink and van Weel68,Reference Truswell and Hiddink69) and weight management(Reference Truswell and Hiddink69,Reference van Weel, Hiddink and van Binsbergen70) . Further public health initiatives may still be required to overcome the ‘problem’ of low levels of nutrition care by PCP, such as international goals for the integration of nutrition into health services and for population receipt of nutrition care.

Some of the reviewed studies suggested that having mandatory nutrition training for PCP would drive PCP to provide nutrition care(Reference Crowley, O’Connell and Kavka39,Reference Pollak, Coffman and Alexander49) . Other literature supports this suggestion(Reference Glanz59,Reference Truswell62,Reference Hautvast, Hiddink and Truswell71) . In one US study that assessed the state of nutrition education through the eyes of students, residents and physicians, it was reported that nutrition education was poorly integrated into the curriculum and that nutrition counselling was rarely witnessed by students during shadowing experiences; what was observed was often outdated or incorrect(Reference Danek, Berlin and Waite72). The residents perceived that they were ill-prepared to offer nutrition counselling and desired further training in behavioural counselling to increase their confidence in educating patients, and the physicians did not remember having any extensive training in nutrition(Reference Danek, Berlin and Waite72). Despite the inclusion of nutrition education in the PCP curriculum, general practitioner trainees in the Netherlands have requested more teaching in nutrition education and the majority of general practitioner trainees (75 %) and PCP (80 %) with less than 3 years’ experience want to learn when and to whom they should refer patients and sources of reliable, evidence-based nutrition information(Reference van Dam-Nolen73). Others note the need for programme educators to be enthusiastic about their subject and incorporate experiential learning into programmes(Reference Gramlich, Olstad and Nasser74). Clearly, there is need for guaranteed nutrition education in PCP training to ensure that PCP develop skills and confidence to provide nutrition care for personal and population health.

Increasing primary-care physicians’ motivation to provide nutrition care

The studies in the present review highlight that many factors influence PCP motivation to provide nutrition care. These factors include: PCP characteristics and those of their patients related to gender and medical conditions(Reference Rohde, Hessner and Lous44,Reference Pollak, Coffman and Alexander49) ; personal interest in nutrition(Reference Dumic, Miskulin and Licanin37,Reference Crowley, O’Connell and Kavka39,Reference Crowley, Ball and Wall40) ; years since completion of medical school(Reference Crowley, Ball and Wall40,Reference Bleich, Bennett and Gudzune47) ; previous unsuccessful attempts in supporting patients to improve their eating habits(Reference Gorig, Mayer and Bock43,Reference Bleich, Bennett and Gudzune47) ; medical educators acting as role models for PCP as a student(Reference Khandelwal, Zemore and Hemmerling36); and training in motivational interviewing(Reference Pollak, Coffman and Alexander49). Evidence exists that PCP nutrition guidance practices are not only determined by barriers(Reference Kushner18,Reference Mihalynuk, Coombs and Rosenfield20,Reference Glanz59,Reference Maiburg, Hiddink and van’t Hof60,Reference Truswell62,Reference Hautvast, Hiddink and Truswell71,Reference Henry, Ogle and Snellman75–Reference Visser, Hiddink and Koelen83) but also by driving forces, self-efficacy factors and nutritional attitudes and beliefs(Reference Mihalynuk, Coombs and Rosenfield20,Reference Britt, Miller and Henderson22,Reference van Weel, Hiddink and Truswell33,Reference Truswell54,Reference Glanz59,Reference Maiburg, Hiddink and van’t Hof60,Reference Truswell, Hiddink and Blom64,Reference Truswell, Hiddink and van Binsbergen66,Reference Truswell, Hiddink and van Weel68,Reference van Weel, Hiddink and van Binsbergen70,Reference Hautvast, Hiddink and Truswell71,Reference Hiddink78–Reference van Weel84) . In the studies reviewed, having a personal interest in nutrition(Reference Dumic, Miskulin and Licanin37,Reference Hseiki, Osman and El-Jarrah38,Reference Gorig, Mayer and Bock43) , having healthy personal eating habits(Reference Hung, Keenan and Fang45) and being a more experienced PCP(Reference Bleich, Bennett and Gudzune47,Reference Pollak, Coffman and Alexander49) appeared to increase PCP perception of their nutrition capability and motivation to provide nutrition care(Reference Dumic, Miskulin and Licanin37,Reference Crowley, O’Connell and Kavka39,Reference Crowley, Ball and Wall40) . Early literature established that physicians with better personal health habits have more positive attitudes towards counselling(Reference Wells, Lewis and Leake85). More recent literature has endorsed that PCP personal interest in nutrition and its effects on health impact positively on nutrition guidance practices(Reference Maiburg, Hiddink and van’t Hof60,Reference Hiddink, Hautvast and Van Woerkum76–Reference Hiddink78,Reference Hiddink and Hautvast82,Reference Visser, Hiddink and Koelen83,Reference Spencer, Frank and Elon86) . This suggests that training in personal health behaviours could be key to integrating nutrition into undergraduate and PCP training to increase PCP interest and confidence to provide nutrition care. Initially, this confidence may only include patient health, and can then be extended to community, regional and global levels to address public health nutrition(Reference Kushner, Graham and Hegazi87,Reference Devries, Willett and Bonow88) .

Increasing primary-care physicians’ opportunity to provide nutrition care

Several factors beyond the control of PCP that impact the provision of nutrition care were identified in the reviewed studies. PCP perceived greater opportunity to provide nutrition care if changes were made at governmental and professional organisation levels, such as mandatory nutrition training and creating health policies that required additional primary prevention and health promotion initiatives to improve public health outcomes(Reference Dumic, Miskulin and Licanin37,Reference Crowley, O’Connell and Kavka39) . The scope of policy changes in prevention and health promotion initiatives could make nutrition a central focus of health care(Reference Kris-Etherton, Akabas and Douglas89,Reference Willett, Rockstrom and Loken90) . Internationally, efforts have been made to strengthen accountability in nutrition for progress in reducing malnutrition(Reference Haddad, Achadi and Bendech91). Additionally, many countries now have policies that focus on prevention and health promotion to support population health, such as the recent Dutch National Prevention Agreement that addressed prevention (and stopping) of smoking, overweight and alcohol abuse for the entire Dutch population and also aimed to strengthen and speed up the prevention programmes(92). Professional organisations for PCP also provide policy. The Royal New Zealand College of General Practitioners’ policy for obesity acknowledges that PCP are ideally placed to identify and manage patients at risk of obesity, related to most New Zealanders visiting a general practitioner annually and many general practitioners forming ongoing relationships with their patients(93). Previously, the Heelsum workshops discussed the problems, opportunities and future possibilities of nutrition guidance by family doctors in a changing world(Reference Truswell, Hiddink and Blom64) and made recommendations that both family doctors and patients need to be empowered in nutrition communication(Reference Truswell, Hiddink and van Binsbergen66,Reference Truswell67) , for the development of supportive environments for nutrition guidance to create synergy between primary care and public health(Reference Truswell, Hiddink and van Binsbergen66,Reference Truswell, Hiddink and van Weel68,Reference Truswell94) and for practice-based evidence for weight management, with an alliance between primary care and public health(Reference Truswell and Hiddink69,Reference Truswell, Hiddink and Green95) , all in acknowledgment of the ongoing relationship and trust patients have in their PCP(Reference Hiddink, Hautvast and van Woerkum96,Reference Van Dillen, Hiddink and Koelen97) . The embedding of family practice in a government’s health policy is also very important(Reference Truswell and Hiddink69).

An innovative approach to obesity care in Australia illustrates the interrelated nature of PCP capability, motivation and opportunity to provide nutrition care(Reference Michie, van Stralen and West27). The ‘Change Program’ was developed to increase PCP confidence and self-efficacy to manage obesity that drew on the therapeutic relationship between patients and their PCP, was supported by evidence-based tools and provided holistic and person-centred care(Reference Sturgiss, Haesler and Elmitt98). This programme uses PCP strengths as reliable and trusted messengers for health care, not only to increase uptake of interventions but also to coordinate, contextualise and deliver their own health and behaviour messages to help PCP at the interface of patients’ and population health(Reference Sturgiss, Haesler and Elmitt99). The programme has been successful in improving PCP confidence in assisting and arranging care for patients(Reference Sturgiss, Haesler and Elmitt98,Reference Ashman, Sturgiss and Haesler100) and is feasible and acceptable for patients with obesity and a strong preference for PCP involvement(Reference Sturgiss, Elmitt and Haesler101).

Study strengths and weaknesses

There are both strengths and weaknesses in the present integrative review. A strength is the wide variety of studies that utilised a range of methodological designs and objectives to provide a broad overview of PCP provision of nutrition care. It can be complex to integrate qualitative and quantitative findings and can introduce bias(Reference Whittemore and Knafl29); however, this potential was reduced by two independent researchers screening thirty-five full-text articles against inclusion and exclusion criteria and a third reviewer being available for discussion with any discrepancies. Data extraction and quality assessment were also performed by two investigators to ensure consistency. As meta-synthesis is an iterative process, emerging themes were constantly reviewed and revised by the investigators. While the methodological quality did not influence inclusion or exclusion of studies, the results of the integrative review should be interpreted with caution related to the poor quality of some studies. Future studies would benefit from being grounded in theory that attempts to explain the behaviours of the target group. In the case of the current review, the COM-B model supports developing multifaceted interventions that simultaneously target PCP capability, motivation and opportunity to provide nutrition care. The findings of the reviewed studies assume there is a fundamental importance of targeting these factors through medical education, although future studies should also consider innovative professional development opportunities for current doctors to improve their practices.

Conclusion

The present review suggests that PCP behaviour related to nutrition care is influenced by three interrelated factors: capability, motivation and opportunity. To support PCP to provide nutrition care, nutrition capability should begin in undergraduate medical training, and continue into PCP training, to create synergy between acquisition of knowledge, motivation and opportunity to become confident in providing nutrition care. Concurrent with nutrition education is the need for motivation to provide nutrition care by educators and mentors reinforcing and modelling the role of nutrition in health. The final component, that of opportunity, should be supported in the practice setting and by governmental and professional organisations, since nutrition care is an integral component, not an optional component, of disease prevention and management in contemporary medical practice.

Acknowledgements

Financial support: This work was supported by the Sir John Logan Campell Medical Fellowship 2017 which allowed J.C. to travel to Europe to instigate the collaboration of this manuscript. The Sir John Logan Campell Medical Fellowship 2017 had no role in the design, analysis or writing of this article. Conflict of interest: None stated. Authorship: J.C. performed the literature search, review and extraction. L.B. contributed to the review and extraction. J.C., L.B. and G.J.H. made substantial contributions to the conception and design of the review and interpretation of the findings. All authors participated in regular meetings about interpretation of studies and manuscript writing. All authors were involved in the drafting of the manuscript and read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have agreed they are accountable for all aspects of the work. Ethics of human subject participation: Not applicable.