Snack foods marketed to children often contain high levels of fat, sugar or sodium(Reference Powell, Szczypka and Chaloupka1). Reduction in the frequency of consumption of unhealthy snack foods is therefore an essential target for paediatric nutrition(Reference Richards, Hackett and Duggan2). Parents play an important role in their pre-school children's diet, by acting as gatekeepers for food types and portion sizes and modelling eating behaviours(Reference Anzman, Rollins and Birch3). As well as specific feeding practices, parental feeding style may be associated with children's diet. Higher parental restriction and lower pressure to eat has been associated with increased adiposity, although this relationship might be partly explained by concern about children's weight(Reference Webber, Hill and Cooke4). It is therefore important to understand parents’ beliefs and perceptions regarding their children's snacking behaviour, in order to intervene effectively.

One area that is attracting increasing attention for understanding and explaining behaviour is social norms. These are the (explicit or implicit) generally accepted rules of a group that can guide group members’ attitudes, beliefs and behaviour. Specific attention has been paid to people's perception of what others eat (descriptive norms) and their perception of what others think is acceptable to eat (injunctive norms). Social psychological research into the role of norms in young people's smoking and alcohol intake has shown that perceived social norms are often inaccurate(Reference Perkins, Haines and Rice5, Reference Perkins and Craig6). This has been observed for both descriptive norms (e.g. the perceived prevalence of binge drinking within the peer group) and injunctive norms (the perceived acceptability of binge drinking within the peer group). Perceived descriptive norms tend to overestimate the prevalence of smoking and binge drinking among peers(Reference Perkins, Haines and Rice5–Reference Rivis and Sheeran7). The same is seen for injunctive norms; young people assume greater social acceptability of smoking or binge drinking among their peers than is shown to be the case when attitudes are measured directly(Reference Bosari and Carey8–Reference Cialdini, Reno and Kallgren10). These observations have led to successful behaviour change initiatives based on providing accurate normative information(Reference Linkenbach and Perkins11, Reference Perkins and Craig12).

The idea that social norms could contribute to unhealthy diets is beginning to attract attention, with both the WHO and the European Commission identifying changing dietary social norms as a policy goal(13). There is evidence that young people's perceived norms for sugar-sweetened drink consumption are associated with their own levels of intake(Reference Perkins, Perkins and Craig14, Reference Lally, Bartle and Wardle15). Adolescents’ intake of snacks and fruit and vegetables has also been shown to be associated with descriptive norms(Reference Lally, Bartle and Wardle15). In adults, there is evidence that social norms are associated with a range of eating behaviours(Reference Ball, Jeffery and Abbott16) and recent experimental data showed that accurate normative information about fruit and vegetable consumption increased men's intentions to increase their own intake(Reference Croker, Whitaker and Wardle17).

Qualitative evidence suggests that social norms and comparisons can guide parents’ beliefs about the quality of their children's diet. For example, one study showed that parents downplay examples of their own children's fussy eating behaviour by drawing comparisons with more difficult children in other families(Reference Webber, Cooke and Wardle18). Parents of children aged between 27 and 54 months frequently said that friends and ‘what other children do’ were sources of information about how to feed their own children(Reference Carruth and Skinner19). One exploratory study tested the hypothesis that social norms mediate the effect of fast-food marketing on parents’ behaviour(Reference Grier, Mensinger and Huang20). The results indicated that parents who watched more fast-food adverts had higher perceived norms for eating fast food, and this made them more likely to give fast food to their own children. There have been no studies of perceived norms for the frequency of children's intake of unhealthy snacks.

The aim of the present study was therefore to examine parents’ perceived descriptive and injunctive norms for children's snack intake and compare them with the reported prevalence and acceptability of unhealthy snacking in the same community. If norm perceptions for unhealthy dietary behaviours follow the pattern seen for tobacco and alcohol, parents would be expected to overestimate both the frequency and acceptability of young children's intake of sweet and savoury snacks.

Methods

Participants

Data for the present study were collected as part of a community survey of psychosocial predictors of diets in pre-school children, The Poppets Study(Reference Sweetman, McGowan and Croker21), carried out in nursery schools and children's centres in one London borough in 2008. Parents with children aged 2–4 years attending the sixty participating nurseries or children's centres were eligible to participate. Details of questionnaire distribution are described elsewhere(Reference Sweetman, McGowan and Croker21). Of the 465 questionnaires returned, thirty-one were excluded for incomplete data and two because the children were out of age range, giving a final sample size of 432. Ethical approval was granted by the University College London Research Ethics Committee (Project ID Number: 0521/003). A power calculation with G*Power(Reference Faul, Erdfelder and Buchner22) indicated this would give 90 % power (P < 0·01) to detect a medium effect size difference between reported behaviour and perceived norms.

Questionnaire design and analysis

Each social norm variable was assessed with one item each for savoury and sweet snacks, following the established methodology(Reference Bourgeois and Bowen23, Reference Perkins24), with question specificity and reference group matched across variables. Prevalence of snacking was assessed by asking respondents how often their own child had sweet and savoury snacks between meals. Acceptability of snacking was assessed by asking respondents to select the most acceptable frequency for each snack type. Perceived descriptive norms were assessed by asking respondents how often they thought other 2–4-year-old children in their local area had sweet and savoury snacks between meals. Perceived injunctive norms were assessed by asking respondents to select the frequency of snacking that they believed was most acceptable to other parents of 2–4-year-old children living in the area. The term ‘unhealthy’ was not used, but all examples of snacks were high in fat, sodium or sugar. Response options were: ‘never/rarely’, ‘once a week’, ‘2–3 times a week’, ‘4–6 times a week’, ‘once a day’, ‘twice a day’ and ‘three or more times a day’, which were recoded into five categories (never/rarely, 1–3 times/week, 4–6 times/week, 1 time/d, ≥2 times/d) to equalise group sizes. To assess misperceptions, perceived descriptive norms were compared with reported prevalence of snacking frequency and perceived injunctive norms were compared with the reported average acceptability of snacking. Wilcoxon signed-rank tests were carried out with the PASW Statistics 18·0 statistical software package (IBM SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) to assess the statistical significance of these differences.

Results

Participant characteristics

The 432 parents or primary caregivers in the sample were ethnically diverse (23 % non-white and 73 % white, 4 % missing ethnicity information). The majority of parents (57 %) owned their home, with 39 % renting public or private housing. Just over half (61 %) had college-level education. In comparison with data on the demographics of the local area, respondents had higher levels of education and home ownership, but were locally representative in terms of ethnicity(25). The average age of the children was 42 months (range 24–59 months).

Snack intake and descriptive norms

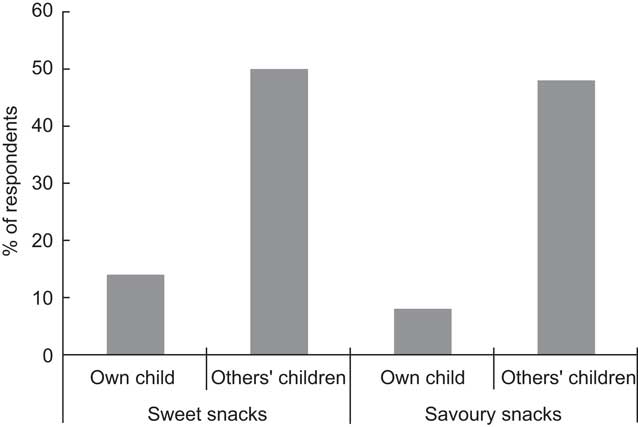

Reported snack frequency varied across the full scale range, with a median frequency of either type of snack of 1–3 times/week (see Table 1). In contrast, the majority of respondents thought that other children ate both types of snack every day. Figure 1 illustrates the difference between parental reports of their own child's intake and their estimates of other children's intake. It shows the proportion of parents who said their own child ate snacks at least 1 time/d compared with the proportion thinking that other children ate snacks at least 1 time/d. More than two-thirds (70 %) of respondents thought that other children ate more sweet snacks than their own child, and 73 % thought other children ate more savoury snacks than their own child. Wilcoxon signed-rank tests confirmed a significant discrepancy between parents’ reports of their own child's snack intake and their estimates of other children's intake (see Table 1).

Table 1 Frequency reports (the percentage and number of respondents who chose each frequency category) and tests of differences (behaviour v. perceived descriptive norms, attitude v. perceived injunctive norms) for each snack type: parents (n 432) of children age 2–4 years, London, UK

Fig. 1 Percentage of respondents indicating that their children or other children eat sweet and savoury snacks at least 1 time/d: parents (n 432) of children age 2–4 years, London, UK

Attitudes and injunctive norms

The median acceptable frequency for giving either type of snack was 1–3 times/week (see Table 1). However, the median perceived injunctive norm (belief about what ‘other parents’ find acceptable) for either type of snack was 4–6 times/week. Figure 2 illustrates the discrepancy for daily snack intake, showing that most respondents did not rate this as acceptable for their own child but believed it was acceptable to other parents. The majority (60 %) of respondents were less accepting of sweet snacks than they believed other parents were (and 63 % for savoury snacks). Wilcoxon signed-ranks test confirmed the discrepancy between parents’ attitudes towards their own child's snacking and their beliefs about other parents’ attitudes.

Fig. 2 Percentage of respondents indicating that it was acceptable to themselves, or to other parents, for children to eat sweet and savoury snacks at least 1 time/d: parents (n 432) of children age 2–4 years, London, UK

Weighted analysis

Because the sample was not entirely representative of the area, we weighted the data based on area-level education and home ownership, using data from the 2001 Census(25). Analyses were re-run using the weighed data and the findings were similar, with significant differences between variables unchanged (analysis not presented here).

Discussion

The present study showed that parents of pre-school children perceive other parents to give their children more unhealthy snacks and to regard snacking as more acceptable than they do themselves. Parents’ perceptions of others’ attitudes and behaviours were therefore more ‘permissive’ than was the case; following a similar pattern to that seen in relation to alcohol and tobacco(Reference Perkins, Haines and Rice5–Reference Larimer, Turner and Mallett9). The reasons why parents hold such misperceptions are not known. In the alcohol and tobacco field, it has been argued that seeing a person smoking or drunk is more vivid and memorable than seeing someone not smoking or sober; and this biases recall(Reference Berkowitz26). It is possible that seeing a child eating unhealthy snacks is more salient than seeing them not eating, or eating healthy food, and therefore recall is biased in the same way. Information about others’ behaviour also comes from indirect sources. Newspaper headlines regularly sensationalise issues around children's diet and obesity(Reference Cohen27) and advertisements representing unhealthy foods as a normal part of the family diet are ubiquitous(Reference Sixsmith and Furnham28); both of which may contribute to misperceptions of what ‘other children’ eat(Reference Grier, Mensinger and Huang20). Giving parents accurate feedback on the snacking behaviour and attitudes of others might have the same beneficial effect observed for alcohol and tobacco(Reference Perkins and Craig6, Reference Linkenbach and Perkins11).

The present study is the first to apply the social norms approach to family diets and several limitations must be acknowledged. The study was conducted in a single area of London, UK which limits generalisability. This was necessary to provide a salient normative reference group(Reference Bosari and Carey8) but the results need to be replicated in other areas. It would also be interesting to test whether similar misperceptions exist when the reference group is wider, for example ‘other parents in the UK’; as might be used in mass media marketing campaigns. Respondents were more educated and affluent than the area average and therefore likely to be feeding their children more healthily(Reference Clark, Goyder and Bissell29). However, weighting the data to match the local population did not diminish the misperception effect.

The present study followed the social norms research tradition of using self-reported behaviours to provide the prevalence data against which to test the accuracy of descriptive norms. However, we recognise that self-report dietary data have limited validity. Given that parenting and the feeding of children are topics that are subject to wide political and moral value-judgements(Reference Clarke30, Reference Lee31), we might expect some degree of under-reporting. Future work should consider using objective measures of snack consumption. However, even if participants were responding in a socially desirable manner, it is nevertheless clear that most parents believe that they feed their own children more healthily than other parents do. Since this cannot logically be true for everyone, it suggests that providing accurate normative information could dispel these beliefs and may have the potential to influence behaviour.

Conclusions

We have demonstrated that parents of pre-school children perceive other people's children to eat unhealthy snacks more frequently than their own child and perceive other parents to be more accepting of frequent snack consumption than they are themselves. Correcting misperceived descriptive and injunctive norms could help motivate parents to limit their children's snack intake.

Acknowledgements

The research was funded by a programme grant from Cancer Research UK. The funding body had no involvement in the design of the study or data collection, analysis or interpretation. The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest. P.L., L.C. and H.C. participated in the design of the study, the data collection and analysis, and the drafting of the manuscript. L.M. and N.B. helped with interpretation of the data and were involved in revising the manuscript. J.W. obtained funding for the study, participated in the design and contributed to the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. The authors would like to thank David Boniface for advice on running the weighted statistical analysis.