The pronounced health challenges faced by Indigenous peoples worldwide are deeply rooted in legacies of colonisation that have generated loss of land and erosion of cultural and social identity(Reference Walker, Lovett and Kukutai1–Reference Adelson4). As a result, Indigenous peoples have been disproportionally affected by food insecurity – a challenge of uncertain or insufficient access to quality, healthy and personally and culturally appropriate/accepted food that persists in the Canadian context(Reference McIntyre5–Reference Anderson, Robson and Connolly8).

In Canada, displacement from traditional territories, forced cultural assimilation, involuntary community relocation to reserves and environmental degradation have threatened Indigenous food systems and the resilience of communities to sustain a traditional diet and lifestyle(Reference Lemke and Delormier9). The 1 673 785 individuals who self-identify as Indigenous in the 2016 Canada Census are a young and growing population, representing three distinct and diverse cultural peoples: First Nations (58·4 %), Inuit (3·9 %) and Métis (35·1 %)(10). In 2016, among the 76·2 % of First Nations peoples with registered Indian status,Footnote 1 approximately 44·2 % indicated primary residence being on reserveFootnote 2 (Reference Adelson4,10) .

As widespread food insecurity among Indigenous households has accompanied transition away from traditional food sources, a nutritional burden has been placed on Indigenous peoples globally(Reference Egeland, Johnson-Down and Cao12–Reference Gracey and King14). Alongside increased burden of chronic disease that has been observed such as type 2 diabetes, cancer and cardiovascular disease(Reference Delormier, Horn‐Miller and McComber7,Reference Anderson, Robson and Connolly8,Reference Rotenberg15–20) , particular concern has been drawn to the increasing prevalence of obesity as a modifiable risk factor for diet-related chronic diseases that are reported to be higher among Indigenous peoples(Reference Egeland, Johnson-Down and Cao12–Reference Gracey and King14,Reference Gionet and Roshanafshar21–Reference Batal and Decelles23) . Understanding nutrition transition within the context of the dual and interrelated structural challenges of food insecurity and obesity confronting Indigenous peoples in Canada can support the adoption of culturally appropriate healthy nutritional policies, programmes and tools to be identified and informed by Indigenous peoples to reduce this nutritional burden and prevent chronic diseases(Reference Egeland, Johnson-Down and Cao12,Reference Gionet and Roshanafshar21,Reference Batal and Decelles23–Reference Power26) .

Over the past century, as First Nations communities have been subject to severe marginalising pressures including, but not limited to, the loss of traditional land, relationships, language and culture caused by colonisation(Reference Daschuk27) and perpetuated by the residential school system(Reference Owen28), they have experienced a rapid transition in diet and lifestyle, characterised by decreased physical activity and a shift towards consumption of energy-dense market-based food(Reference Young, Reading and Elias16,Reference Haman, Fontaine-Bisson and Batal17,Reference Reeds, Mansuri and Mamakeesick29,Reference Batal, Gray-Donald and Kuhnlein30) . This nutrition transition has been identified to play a key role in the rising rates of obesity-related chronic diseases in these populations(Reference Egeland, Johnson-Down and Cao12,Reference Young, Reading and Elias16,Reference Haman, Fontaine-Bisson and Batal17,Reference Batal, Gray-Donald and Kuhnlein30–Reference Gittelsohn, Wolever and Harris32) , with this trend observed to be driven by a range of processes – first and foremost colonial policies and practices that enforced physical displacement from these lands, disrupting access to environments that enable engagement in traditional food activities(Reference Reading and Wien2,Reference Richmond and Ross3,Reference Daschuk27,Reference Owen28) ; a changing food environment from the introduction of various food sources and imported goods(Reference Sharma, Gittelsohn and Rosol33); and increased engagement in market economy activity, leaving less time to engage in traditional food practices(Reference Sharma, Gittelsohn and Rosol33).

In conjunction with this ongoing nutrition transition, the 2012 Canadian Community Health Survey (CCHS) observed disproportionately high rates of food insecurity among First Nations households (20 %) compared with non-Indigenous households in Canada (8 %)(Reference Rotenberg15). The CCHS, however, excludes First Nations households living on reserve, and therefore this prevalence of food insecurity is considered to underestimate the levels among all First Nations households(Reference Tarasuk, Mitchell and Dachner34). In line with this, results from the First Nations Regional Health Survey Phase III, which includes Indigenous peoples living on-reserve and in northern communities, indicate 50·8 % of First Nations adults report their households as food-insecure(35). While the nine food security questions in the First Nations Regional Health Survey are similar to the eighteen-item Household Food Security Survey Module in the CCHS, more than one individual within the same household could respond to the survey(35), and this may therefore impact the estimated prevalence of food insecurity. A deepened understanding of food insecurity in First Nations communities and opportunities to address risks of chronic diseases, including its implications for holistic health and wellness, is therefore needed(Reference Reading and Wien2,Reference Richmond and Ross3,Reference Egeland, Johnson-Down and Cao12,Reference Kuhnlein, Receveur and Soueida13,Reference Skinner, Hanning and Tsuji24–Reference Power26) .

Food insecurity has been associated with the inadequacy of food supplies in households, resulting in reduced quality or desirability of food consumed, including a low healthy eating index score tied to a decreased consumption of fruit and vegetables, dairy products and grains(Reference Huet, Rosol and Egeland36), alongside attention to the importance of also considering ‘cultural food sovereignty’(Reference Power26). Reduced nutrient intake and poor dietary quality related to food insecurity have contributed to obesity with implications for risks of chronic diseases(Reference Egeland, Johnson-Down and Cao12,Reference Kuhnlein, Receveur and Soueida13,Reference Young, Reading and Elias16,18,Reference Huet, Rosol and Egeland36,Reference Holben, Barnett and Holcomb37) .

The prevalence rates of obesity have also been found to be higher among First Nations people living on-reserve and in northern communities (34·8 %) as indicated in the First Nations Regional Health Survey 2008/2010(35), as well as among First Nations individuals living off-reserve (31 %) in comparison with the total population in Canada (17 %)(Reference Rotenberg15). The relationship between food insecurity and excess weight is not well understood(Reference Morales and Berkowitz38). However, growing interest in food security as a determinant of health is expanding the emergence of literature on the positive association between food insecurity and obesity(Reference Olson39–Reference Lyons, Park and Nelson44). This relationship has been linked to eating patterns characterised by a high consumption of low-cost, energy-dense and nutrient poor foods(Reference Young, Reading and Elias16,Reference Townsend, Peerson and Love42,Reference Lyons, Park and Nelson44–Reference Drewnowski and Specter46) . This represents a dual interrelated concern whereby obesity is a challenge tied to an overabundance of energy-dense food, while the lack of affordable and accessible nutritious foods is an issue contributing to food insecurity. With First Nations communities observed to suffer disproportionally from both the burden of food security and of obesity(Reference Batal and Decelles23), understanding the patterns of food insecurity and ties with obesity, therefore, merits attention in order to identify culturally relevant strategies to address this dual public health challenge.

While a few studies have examined the association between food insecurity and obesity, existing research has yielded conflicting findings across women and men as well as across levels of food insecurity measured – and has primarily examined non-Indigenous populations in Canada(Reference Hanson, Sobal and Frongillo40–Reference Townsend, Peerson and Love42,Reference Lyons, Park and Nelson44–Reference Drewnowski and Specter46) . To our knowledge, there has been no study that has investigated the association between food insecurity and obesity within an Indigenous context in Canada, in particular on-reserve First Nations communities. Further, as data from the CCHS excludes First Nations living on-reserve, diet-related health concerns associated with unique food security challenges faced by First Nations communities(Reference Power26) heighten the need for this nutritional and public health challenge to be assessed. This would support a better understanding of its differential effects within this population while not diminishing focus on the need to address the driving forces underlying food and nutrition challenges.

To deepen understandings of patterns of food insecurity and diet-related health concerns, our study examines the demographic and socioeconomic factors associated with household food insecurity in First Nations communities in four provinces of Canada, with attention to the relationship between household food insecurity and obesity. In the current study, the level of food insecurity reported from the 2008–2013 First Nations Food, Nutrition and Environment Study (FNFNES) was defined as a household’s inability to access food, including due to financial constraints(Reference Domingo47–Reference Chan, Receveur and Sharp51). The objectives of this article are to contribute to understandings of food insecurity regarding influences on its presence in First Nations households, as well as how this is associated with obesity. Given the challenges with understanding culturally appropriate indicators of food security, which includes consideration of access to traditional foods through practices such as hunting, gathering, fishing and trading, we wish to stimulate considerations about nutrition transition and the value of Indigenous-led approaches to health-promoting nutritional policies, programmes and tools to reduce the burden of food insecurity, obesity and chronic diseases.

Methods

Study

Data analyses were conducted using inputs from the FNFNES, a research initiative with a cross-sectional study design, regionally representative of First Nations communities south of the 60th parallel in Canada. FNFNES was supported by a resolution passed by the Assembly of First Nations in 2007 and was a collaborative partnership between the Assembly of First Nations, Indigenous Services Canada, the University of Northern British Columbia, the Université de Montréal and the University of Ottawa(Reference Chan, Receveur and Batal48–Reference Chan, Receveur and Sharp51). FNFNES was developed in response to growing concerns by First Nations communities regarding the presence of environmental contaminants in traditional food systems, and the need to document and address food-related health challenges across communities. This research was guided by the Tri-Council Policy Statement: Ethical Conduct for Research, including Chapter 9 of the Tri-Council Policy Statement, ‘Research Involving the First Nations, Inuit and Métis People of Canada(52)’. In addition, the First Nations principles of Ownership, Control, Access and Possession (OCAPTM)(53) guided this undertaking to ensure ethical health research and appropriate engagement with First Nations communities. Engagement with First Nations leadership at the national, regional and community levels informed the FNFNES project design, including the survey questionnaire, study objectives, methodology and implementation, with funding support from the First Nations and Inuit Health Branch, Indigenous Services Canada. Ethical approval was obtained from the Ethics Research Board at Health Canada, the University of Northern British Columbia, the Université de Montréal, University of Ottawa and the University of British Columbia.

Sampling frame

Using an ecological zone framework, a systematic multistage random sampling method was employed to select participants from communities from the provinces of British Columbia, Alberta, Manitoba and Ontario in Canada. This sampling strategy aimed to establish equal representation of communities from the Assembly of First Nations regions (in this case provinces) and ensure the likelihood of highly populated communities to be sampled. Within each community, questionnaire data were collected from a single adult (self-identified as of First Nations descent, age ≥19 years, living on-reserve) in each selected household. Within the selected households with more than one adult, an individual who self-identified as a First Nations person living on-reserve with the next birthday was invited to participate in the study.

Between 2008 and 2013 of the FNFNES’s ten-year project timeline (2008–2018), 5355 households from fifty-eight communities were randomly selected across British Columbia, Alberta, Manitoba and Ontario. Of the 5355 households sampled, a total of 3847 adults participated in household interviews, representing a participation rate of 74·5 %. Households were excluded from the survey if the respondent did not meet the inclusion criteria, was unable to participate due to health reasons (deafness, cognitive impairment) and if homes were vacant.

Measures

Data utilised in the current study were collected from the social, health and lifestyle questionnaire and food security questionnaire administered to participating households by a trained community member. The social, health and lifestyle questionnaire in the FNFNES incorporates questions from the CCHS and previous work with Indigenous populations in Canada(Reference Kuhnlein, Receveur and Chan54) and collects information on general health status, sociodemographic characteristics and measured and self-reported height and weight. If accepted to be measured, weights were recorded using a Seca 803 digital scale with the participants lightly clothed. Height was measured using a measuring tape on shoeless participants on an even surface. BMI was calculated as weight/height (kg/m2) for 691 participants with both measured and self-reported height and weight, 922 participants with measured height and weight only, and 1749 participants with self-reported measures only. To account for a potential response bias among self-reported cases of height and weight, adjustments were made through the addition of estimated bias determined using a paired t test to estimate differences in means in BMI between measured and self-reported values. Adjustments were applied to self-reported BMI in Ontario and Alberta, but were not necessary for British Columbia and Manitoba. Participants were considered obese if their BMI was ≥30·0(55).

The food security questionnaire used in the FNFNES is the income-related Household Food Security Survey Module. Household Food Security Survey Module, developed by the US Department of Agriculture, is internationally recognised as a measure of household food insecurity(Reference Bush and General56) for comparative purposes and has been used in national surveys in Canada, such as the CCHS(Reference Tarasuk, Mitchell and Dachner34). The food security questionnaire comprises eighteen questions to measure self-reports of household food insecurity due to financial constraints within a 12-month period prior to being surveyed. Ten of the eighteen questions measure adult experiences of food insecurity, and the remainder measure food insecurity among households with children under the age of 18. From the survey, the degree of household food insecurity was determined from a numerical scale based on the number of affirmed responses (‘yes’, ‘often’ or ‘sometimes true’, ‘almost every month’ or ‘some months, but not every month’). Household food security status was identified by categorising the severity of food insecurity from the food security numerical scale(Reference Tarasuk, Mitchell and Dachner34,Reference Bush and General56) . In the current study, household food security status was described using the following categories(Reference Tarasuk, Mitchell and Dachner34): (i) food security (no affirmed response); (ii) marginal food insecurity (no more than one affirmed response on the adult food security scale or child food security scale); (iii) moderate food insecurity (2–5 affirmed responses on the adult food security scale, and 2–4 affirmed responses on the child food security scale); (iv) severe food insecurity (≥6 affirmed responses on the adult food security scale, and ≥5 affirmed responses on child food security scale).

Statistical analysis

Prevalence estimates of household food security status were derived for marginal, moderate and severe food insecurity, as well as total household food (in)security. Prevalence estimates of obesity were also determined for female and male respondents living in food-secure households, as well as households experiencing marginal, moderate and severe food insecurity.

Multivariate logistic regression modelling was carried out in the current study to examine: (i) sociodemographic predictors of household food insecurity, and (ii) the relationship between household food insecurity and obesity in First Nations communities in British Columbia, Manitoba, Alberta and Ontario. In the first model, sociodemographic predictors of household food insecurity were examined through multivariate logistic regression modelling using the backwards-stepwise selection method. The outcome variable of interest, household food insecurity, was dichotomised as food-secure v. food-insecure (combining marginal, moderate and severe subcategories). Sociodemographic predictors identified in a review of the literature (Table 1) were entered into the model, and the least significant predictor was removed in a stepwise process using a preliminary significance level of α <0·1. The fit of the model was assessed using the Akaike Information Criterion and Hosmer and Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test. Collinearity was assessed and variables identified to be strongly associated with each other were removed from the model. Two-way interactions were examined among significant predictors contained in the model; however, significant interactions that contributed meaningfully to the model were not found. Predictors retained in the final model contributed to model fit and met statistical significance at P < 0·05 and based on the Type III Sum of Squares.

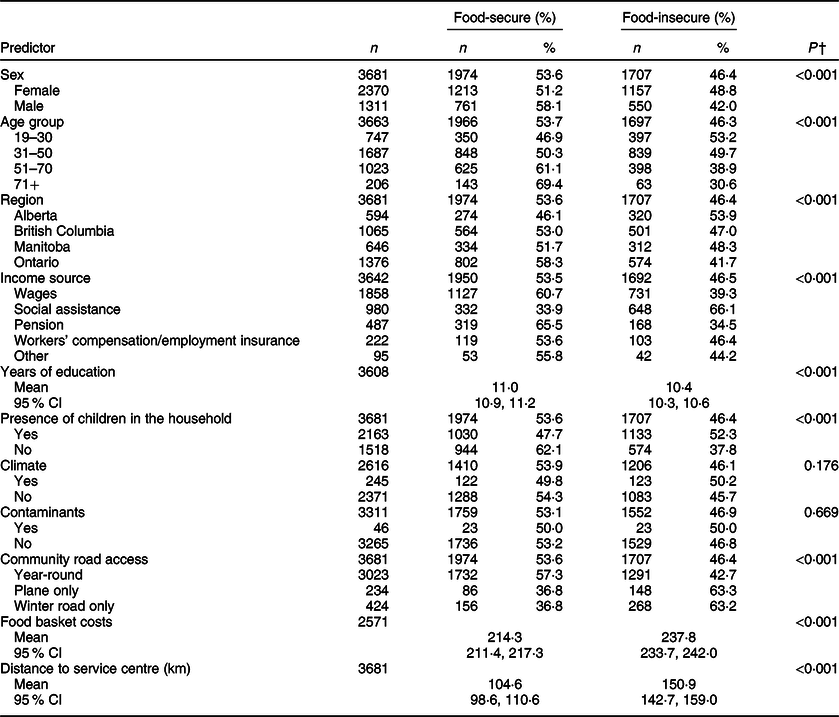

Table 1 Variables explored as potential predictors of food insecurity among First Nations respondents*

FNFNES, First Nations Food, Nutrition and Environment Study; SHL, social, health and lifestyle.

* FNFNES. Data are unweighted.

† Measure of income as captured by the SHL questionnaire in FNFNES was the main source of information. The questionnaire does not capture annual wages and salaries among household respondents.

‡ Based on question 9a and 9b of the SHL questionnaire in FNFNES.

§ This variable was obtained from question 8b of the SHL questionnaire in FNFNES.

‖ Food basket costs were measured based on sixty-seven basic food items using Health Canada’s 2008 National Nutritious Food Basket Tool. Distance to service centre was measured from road access to a service centre (access to banks, suppliers and government services)(Reference Domingo47–Reference Chan, Receveur and Batal49,Reference Basiotis and Lino57) .

In the second model, the relationship between household food insecurity and obesity was examined with bivariate and multivariate logistic regression to assess the odds of obesity for individuals living in food-insecure households. The outcome variable, BMI, was dichotomised to assess the presence or absence of obesity in First Nations households by food insecurity status. The variable, household food insecurity status, was the main effect of interest and was classified into marginal food insecurity, moderate food insecurity, severe food insecurity and food security. Bivariate analyses were carried out to assess differences in the association between obesity and the primary explanatory variable, household food insecurity, with each sociodemographic variable of interest. Statistical effect sizes for household food insecurity were estimated for female and male respondents separately using the three levels of food insecurity. In the multivariate model, the odds of obesity among food-insecure households was determined adjusting for the variables age group, region, main source of income and years of education (Table 1). Unadjusted and adjusted OR were calculated, and 95 % CI for OR were obtained. Although no significant interactions were found in the multivariate model, gender-specific analyses were conducted to account for differences in dietary quality between females and males. All statistical analyses were conducted using the Statistical Analysis Software (SAS), version 9.4 (SAS Institute), and observations with missing values were excluded.

Results

Table 2 provides a description of demographic and socioeconomic characteristics of the 3681 participants who responded to the household food security questionnaire (2370 women and 1311 men). Food security status responses of participants who answered ‘don’t know/refused’ to at least one of the first three food security questions were excluded and treated as missing values. Participants’ age ranged from 19 to 96 years, and the average age of female and male respondents was 44 and 46 years, respectively. Almost half (46·4 %) of these respondents reported some level of household food insecurity, with 9·5 % experiencing marginal food insecurity, indicative of concerns regarding adequate and secure access to food; 27·9 % experiencing moderate food insecurity, demonstrating experiences with compromises in the quality and/or quantity of food; and 8·9 % experiencing severe food insecurity, reporting a disruption of eating patterns and reduced food intake. For households where the respondent was female, 10·6 % experienced marginal food insecurity, 29·6 % were moderately food-insecure and 8·7 % demonstrated severe food insecurity. In households where the respondent identified as male, 7·7 % experienced marginal food insecurity, while 24·9 % were categorised as moderately food-insecure and 9·3 % reported severe food insecurity.

Table 2 Distribution of study participants by demographic and socioeconomic characteristics*

* First Nations Food, Nutrition and Environment Study. Data are unweighted. Totals may vary due to the exclusion of missing values for participants of the study. Percentages may not add up to 100 % due to rounding.

† % distributions for categories and sub-categories.

‡ % distributions for each subcategory category by gender [gender distribution of category total].

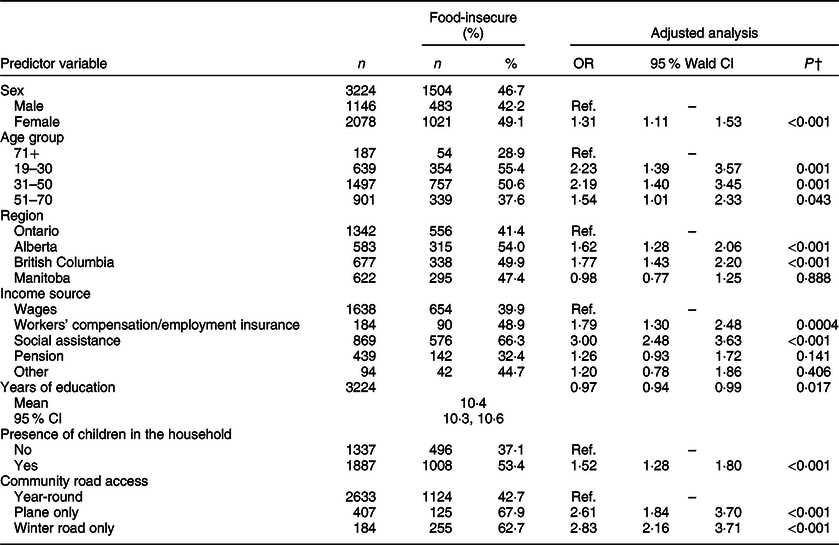

The prevalence of food insecurity varied across demographic and socioeconomic characteristics of the household (Table 3). In multivariate analyses, the rates of food insecurity were highest among surveyed household respondents who were female (49·1 %), between the ages of 19 and 30 (55·4 %), from Alberta (54 %), in households with children (53·4 %) and receiving social assistance as a main source of income (66·3 %) (Table 4). Respondents from households that were food-insecure had, on average, 10 years of education, while respondents from food-secure households had an average of 11 years of education. Among households with children, 32·5 % experienced moderate food insecurity, 11·1 % reported marginal food insecurity and 8·7 % were severely food-insecure. In comparison, 21·4 % of households without children experienced moderate food insecurity, while 7·6 % indicated being marginally food-insecure and 9·2 % were severely food-insecure. When compared with food-secure households with children (<18 years of age), food-insecure households with children had a greater average number of individuals residing in the household (5·2 compared with 4·8) and a larger ratio of persons under 15 years to persons ≥15 years of age in the household (1·1 compared with 0·97).Footnote 3 Additionally, higher rates were found among First Nations households in communities with limited road access (63·3 % in the five communities accessible by plane only, and 63·2 % in the seven communities accessible by winter road only). Table 4 presents the adjusted OR for food insecurity among First Nations households for each demographic and socioeconomic variable in the final multivariate logistic regression model of significant predictors of food insecurity. No statistically significant first-order interactions were found in the multivariate analysis.

Table 3 Prevalence and bivariate analysis of predictors of food insecurity*

* First Nations Food, Nutrition and Environment Study. Data are unweighted.

† P-values correspond to a bivariate analysis of food security status and predictor and were determined from either χ 2 test or t test.

Table 4 Prevalence of food insecurity by sociodemographic predictor variables and adjusted OR for household food insecurity (n 3224)*

* First Nations Food, Nutrition and Environment Study. Data are unweighted.

† P-values correspond to a multivariate logistic regression analysis of food security status and predictor variables. R 2 = 17 %. The analyses excluded participants with missing values for all predictor variables accounted for in the model. The variables excluded in the backward-stepwise selection method due to a lack of statistical significance and power include climate, contaminants and food basket costs.

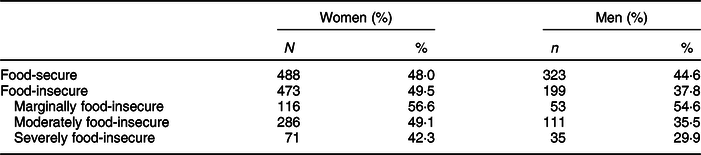

The prevalence rates of obesity were also high among the 3364 participants with calculated BMI in the sample, with minor differences reported between food-secure and food-insecure households. For both female and male respondents, the prevalence rates of obesity were highest in marginally food-insecure households and lowest for severe food-insecure households (Table 5). Female respondents living in marginally food-insecure households had an average BMI of 31·8 kg/m2. The average BMI for female respondents living in moderate food-insecure households was 30·4 and 29·3 kg/m2 for females residing in severely food-insecure households. For male respondents residing in marginally food-insecure households, the average BMI was 30·2 kg/m2, while male respondents living in moderate and severe food-insecure households had an average BMI of 28·9 and 28·2 kg/m2, respectively.

Table 5 Prevalence of obesity by food security status for women and men*

* First Nations Food, Nutrition and Environment Study. Data are unweighted. Percentages may not add up to 100 % due to an exclusion of participants with a BMI classification of overweight (25.0–29.9), normal weight (18·5–24·9) or underweight (<18·5).

In both bivariate and multivariate logistic regression gender-specific analyses, the odds of obesity were highest among marginally food-insecure households in comparison with food-secure households. Table 6 shows the gender-specific unadjusted and adjusted OR for obesity among individuals living in marginally, moderately and severely food-insecure households compared with individuals living in food-secure households. After adjustments were made for age, income, years of education and region, higher odds of obesity among marginally food-insecure households were observed for both male and female respondents. For male respondents only, lower odds of obesity among severely food-insecure households were found after adjusting for confounding variables.

Table 6 Logistic regression analysis of obesity associated with three different levels of household food insecurity†

*P < 0·05; **P < 0·01; significantly different from food security.

† First Nations, Food Nutrition and Environment Study. Data are unweighted.

‡ OR from a multivariate logistic regression adjusting for age, income, years of education and region. The analyses excluded participants with missing values for all variables accounted for in the model.

§ Reference category.

Discussion

The FNFNES provided the opportunity to examine the patterns of food insecurity, as well as its associations with obesity in First Nations communities, south of the 60th parallel, in the Canadian provinces of British Columbia, Alberta, Manitoba and Ontario. As one of the first published examinations of this dual interrelated challenge among First Nations households, our study contributes to the scholarship on nutrition transition and emerging literature focusing on food insecurity and obesity as priority areas for action.

A very high prevalence of food insecurity (46·4 %) was observed among First Nations households surveyed in First Nations communities of Canada. This reveals a particular challenge to ensuring food security compared with the considerably lower 2012 CCHS levels of food insecurity among the general Canadian population that have attracted considerable concern (British Columbia 12·7 %; Alberta 11·5 %; Ontario 11·7 %; Manitoba 12·1 %)(Reference Tarasuk, Mitchell and Dachner34). Differences in the levels of food insecurity observed confirm how the omission of First Nations living on-reserve in the CCHS could underestimate the degree of food insecurity being experienced across Canada, as well as draw attention to the extreme injustice presented by the disproportionately higher rates for First Nations living on-reserve. This has implications for identifying Indigenous-led health promotion and prevention strategies and ensuring that approaches taken are culturally safe and reflective of Indigenous priorities.

The predictors of food insecurity that are associated with highest odds of food insecurity within First Nations households – households within communities without year-round road access, respondents who are female, receiving social assistance, presence of children in the household, years of education ≤10, younger age (< 50) and residing in British Columbia or Alberta – highlight points for interventions to be considered. These sociodemographic characteristics were found to be significantly associated with higher odds of household food insecurity, consistent with studies examining the determinants of food insecurity in Indigenous households in other Canadian settings(Reference Willows, Veugelers and Raine58–Reference Guo, Berrang-Ford and Ford61).

The interrelated challenge of food insecurity and obesity observed in our study has its roots in land dispossession and the ongoing impacts of colonisation that have undermined Indigenous peoples’ connection to the land and its resources(Reference Lemke and Delormier9). Although we did not directly probe these drivers, the differences we observed among the predictors of First Nations household food insecurity can be best understood within the context of delocolonisation of food systems and the underlying stresses to traditional, historically sustaining Indigenous food systems. These stressors to Indigenous food systems are related to land dispossession, forced cultural assimilation through residential schools, and community relocation, which have been examined in other published work in Canada(Reference Lemke and Delormier9,Reference Daschuk27,Reference Owen28) . For many Indigenous communities, the natural environment as a context for accessing food, water and livelihood represents an essential pathway to food security(Reference McIntyre5,Reference Power26) . Through gathering, harvesting and sharing of local plant or animal resources, the holistic health and wellness of Indigenous peoples has long been sustained by their food systems and deep relations with the environment(Reference Richmond and Ross3,Reference Power26) .

As experiences of food insecurity differ between women and men, we recognise our inability to identify specific details, such as individual’s marital status or whether female respondents were responsible for food preparation, as a potential limitation of our study’s questionnaire design. Further, gender inequalities faced by Indigenous women as a consequence of reduced access to resources, such as land, education and agricultural inputs, have been previously exposed as structural determinants of food insecurity(Reference Lemke and Delormier9,Reference Kuhnlein, Burlingame and Erasmus62) . Studies have also found that women compromise their own food security by altering their eating patterns to ensure other members within the household are food-secure(Reference McIntyre63–Reference Martin and Lippert65). For example, when food is limited in the household, women have been described to skip meals or delay eating in order to prevent hunger among children in the household(55,Reference Bush and General56) . While the high prevalence of food insecurity among female respondents may point towards efforts taken by them to prevent food insecurity among children, findings consistently show that households with children experience greater food insecurity compared with households without children(Reference Tarasuk, Mitchell and Dachner34,Reference McIntyre63) .

In Canada, low income levels have been identified as a primary barrier to healthy eating or obtaining food that meets individual’s preferences and needs(Reference Tarasuk66,Reference Li, Dachner and Tarasuk67) . In the FNFNES survey, from which the current study has drawn major inputs, precise income level was not measured as an indicator of low socioeconomic status, although household crowding, receiving social support and education level were considered(Reference Huet, Rosol and Egeland36). Food insecurity in households with children is most prevalent among families led by a single parent and households depending on social assistance as a source of income(Reference Li, Dachner and Tarasuk67,68) . The presence of more family members has placed an increased burden on household resources with implications on food insecurity(Reference Li, Dachner and Tarasuk67,Reference Blanchet and Rochette69) . With regard to households with children, food-insecure households had, on average, more individuals living within the household compared with those that were food-secure. Further, food-insecure households had a greater number of individuals under the age of 15 (ineligible to participate in the labour market) who may have limited capacity to contribute to their household’s overall income. An association between food insecurity and income levels also indicates that households receiving social assistance or dependent on employment insurance/workers’ compensation are at a higher risk as these sources of income may not be sufficient to ensure food security(Reference Li, Dachner and Tarasuk67,Reference Power70) .

While the current study was not designed to conduct a provincial comparative analysis of food insecurity, households within the province of British Columbia and Alberta were at higher odds of food insecurity compared with those in the province of Ontario. Provincial variations observed in food insecurity are likely to be tied to differences in the average cost of food in those provinces(Reference Chan, Receveur and Batal48–Reference Chan, Receveur and Sharp50,71) and differences in provincial social assistance policies and programmes(Reference Béland and Daigneault72). Additional factors may be linked to the number of participating communities located in rural, remote or isolated regions within each province, as households residing in communities accessible by winter road or plane only had higher rates of food insecurity compared with households in communities with year-round road access.

We notably examined the dual interrelated challenges of food insecurity and obesity in the current study. While a non-linear association observed between household food insecurity and obesity derives from a cross-sectional design and, therefore, does not infer causality, the public health challenge that this exposes to exist calls for identifying culturally relevant approaches to reduce chronic disease risk factors among First Nations communities.

In our study, higher odds of obesity were found for both female and male respondents living in marginally food-insecure households compared with food-secure households. In comparison to women living in food-secure households, women living in marginally food-insecure households had higher odds of obesity, an association similar to that observed among men. However, the odds of obesity for men living in severe food-insecure households were lower in comparison to men living in food-secure households. While an association between living in severe food-insecure households and obesity was observed among women, this was not statistically significant. These results are consistent with findings of higher levels of overweight or obesity at low or intermediate levels of food insecurity and lower BMI observed at severe levels of food insecurity compared with food-secure households in non-Indigenous populations(Reference Hanson, Sobal and Frongillo40–Reference Adams, Grummer-Strawn and Chavez43).

A rapid change in diet and lifestyle, characterised by a forced shift from traditional food use towards consumption of energy-dense market-based foods, has placed a high burden of chronic diseases among Indigenous peoples globally(Reference Kuhnlein, Receveur and Soueida13,Reference Sharma, Gittelsohn and Rosol33,Reference Power70,Reference Mead, Gittelsohn and Kratzmann73) . This observed transition is characterised by an involuntary decrease in the use of traditional foods over time across Indigenous populations and particularly among younger individuals(Reference Kuhnlein, Receveur and Soueida13,Reference Sheikh, Egeland and Johnson-Down31) . With an extensive documentation of a steep growth in the prevalence of obesity over time(Reference Batal and Decelles23), nutrition transition and links to chronic diseases are indicative of a forced transformation in diet and lifestyle observed in a context where options have been influenced by processes favouring reliance on processed foods(Reference Reading and Wien2,Reference Richmond and Ross3,Reference Young, Reading and Elias16,Reference Haman, Fontaine-Bisson and Batal17,Reference Batal, Gray-Donald and Kuhnlein30–Reference Sharma, Gittelsohn and Rosol33,Reference Bhawra, Cooke and Hanning74–Reference Batal, Johnson-Down and Moubarac76) .

Consistent with prior observations of similar associations linking higher obesity with lower levels of food security, these studies often point to the reduced quality of purchased food when concerns about food access are present(Reference Hanson, Sobal and Frongillo40,Reference Lyons, Park and Nelson44) . Energy-dense, nutrient-poor food is often made available at low cost and is usually consumed by households experiencing financial constraints(Reference Drewnowski and Specter46). For this reason, risks of obesity from diets composed of affordable, energy-dense foods are a concern among food-insecure households(Reference Drewnowski and Specter46), particularly in households with ‘marginal food insecurity’ whose food choice is limited due to a lack of money. In a study examining community perspectives on the relationship between food insecurity and obesity, First Nations and Métis parents perceived low income as an underlying factor of food insecurity, and reliance on energy-dense food as the most affordable coping option(Reference Béland and Daigneault72). Similarly, changes in dietary practices observed among Inuit communities, especially those receiving income support, have also revealed their vulnerability to purchasing processed foods(Reference Béland and Daigneault72).

Contrastingly, when households experience compromises in the quantity of food or reduced food intake due to severely food insecure levels, differential impacts on individual body weight may be observed. The lower odds of obesity observed in the current study among severe food-insecure households may be tied to a decrease in energy intake due to underconsumption and disrupted eating patterns, contributing to weight loss over time. Decreased consumption and reduced energy intake have been shown to lower obesity at higher levels of food insecurity(Reference Hanson, Sobal and Frongillo40).

Given the persistence of structural determinants driving the association of obesity with food insecurity, it is critical that solutions be explored not in individualised behavioural approaches often characterised as ‘shaming’ but rather on modifications to the circumstances undermining food security itself – and in a culturally appropriate manner(Reference Warbrick, Came and Dickson77). Such approaches could strengthen local food systems and reduce the burden of food insecurity and obesity that is highly prevalent in the First Nations communities.

The results of the current study substantiate the need for further investigations considering dietary intake and food supply when examining the association between food insecurity and obesity within First Nations communities. Until further work is undertaken, the current results should be interpreted with caution. However, given the health inequities already faced by this population, the potential consequences of both food insecurity and obesity on individual’s health and community wellness may risk furthering health challenges. The high and disproportionate burden of food insecurity and obesity among First Nations communities, therefore, represents priority areas for action. A consideration for food sovereign approaches in identifying interventions to strengthen local food systems can present opportunities to improve equitable access to healthy, affordable food with attention given to cultural appropriateness. This is necessary as efforts to mitigate food insecurity without concern for nutritional quality and access to culturally relevant food may limit the impact of prevention and health-promoting strategies aimed at addressing food insecurity and obesity.

Strategies targeted at improving the availability and access to affordable, culturally appropriate, healthy foods are essential for promoting sustainable and community-driven actions to ensure food security among First Nations households in remote or isolated communities. Indigenous-led food sovereign approaches aimed at protecting traditional food practices and improving access to culturally appropriate, healthy and affordable foods can present opportunities to ensure long-term food security against ongoing colonial pressures(Reference Desmarais and Wittman78). Engagement with First Nations, Inuit and Métis communities, the government and key stakeholders working in the areas of food, nutrition and chronic diseases could inform the development of sustainable and multifaceted approaches in support of Indigenous-led action on food insecurity.

The current study contributes to improving the understanding of factors underlying food insecurity and obesity in First Nations communities, thus facilitating the needed discussion on the value of Indigenous-led food sovereign approaches to enhance food security, including access to culturally appropriate, healthy and affordable food. There are, however, limitations to the current study. While the data utilised from FNFNES are regionally representative of First Nations communities in Canada, the cross-sectional design of the study presents limitations with regard to drawing inferences on a cause-and-effect relationship of the association between food insecurity and obesity. Additional socioeconomic and demographic characteristics related to the prevalence of household food insecurity were not measured by the FNFNES survey, such as the precise income level, marital status, family medical history and disordered eating patterns. Future studies led and informed by Indigenous partners and communities that assess community-based interventions to improve food security and nutrition are needed to identify culturally appropriate responses.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: The authors would like to acknowledge all participating community members and leadership provided to inform the study. Financial support: Data used in this analysis are from the First Nations Food, Nutrition and Environment Study (FNFNES) funded by the First Nations and Inuit Health Branch, Indigenous Services Canada. Our analysis of the FNFNES dataset was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research through funding from the ‘Food systems and health equity in an era of globalisation: Think, eat and grow green globally (TEG3)’ (FRN 115207), a health equity grant research programme. Conflict of interest: None. Authorship: A.D., J.S. and M.B. designed the concept and planned the manuscript. H.M.C., M.B. and T.S. are principal investigators, and H.S. and C.T. are co-investigators of FNFNES, which provided the data for the current analyses. K.F. advised on FNFNES research design and coordinated data collection for FNFNES. A.D., J.S. and M.B. wrote the manuscript; M.G., H.W., A.I., K.F., T.S., C.T., H.S. and H.M.C. edited the manuscript for content and clarity. A.D., J.S., M.B., M.G., A.I. and H.W. guided the analysis and analysed the data. Ethics of human subject participation: The current study was conducted according to the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki and was guided by the principles of the Canadian Institutes of Health Research Guidelines for Health Research Involving Aboriginal People, and the Tri-Council Policy Statement: Ethical Conduct for Research Involving Humans. All procedures involving human participants were approved by the Research Ethics Board at Indigenous Services Canada, the University of Northern British Columbia and the Université de Montréal. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. The current study was approved by the ethics board at the University of British Columbia.