Dietary risk was shown to be responsible for more than one-third of deaths worldwide in 2013(1). Nutritional behaviour has thus been targeted by the WHO so as to reduce the current increase in non-communicable diseases(2). At each life stage, a balanced, diversified diet is necessary. Adolescence is one of the most crucial stages in life, requiring specific nutrition(Reference Das, Salam and Thornburg3). Adolescence and early adulthood correspond to key transition periods for acquisition of health behaviours (e.g. tobacco and alcohol consumption, diet-related habits, physical activity and sleep, etc.) that otherwise might later provoke non-communicable diseases(Reference Sawyer, Afifi and Bearinger4). Important changes in health behaviour may occur during this period, while previously acquired habits may be strengthened(Reference Winpenny, Penney and Corder5–Reference Nelson, Story and Larson7).

In Europe and the USA, socio-economic disparities in mortality and morbidity rates, as well as in perceived health, are widening(Reference Gallo, Mackenbach and Ezzati8–Reference Sommer, Griebler and Mahlknecht11). Nutritional issues are also involved(Reference Wu, Ding and Wu12–Reference Chung, Backholer and Wong15). A reference literature review focusing on diet disparities concluded that, in adult populations in industrialized countries, a socio-economic gradient existed(Reference Darmon and Drewnowski16). Indeed, consumption of whole grains, fresh fruits and vegetables and low-fat dairy products increased with socio-economic status (SES), while that of less healthy products such as refined grains and added fats decreased. In a more recent expert report comprising a comprehensive literature review on socio-economic diet disparities, conclusions pertaining to adults also tended to converge towards a socio-economic gradient, despite studies heterogeneously available according to food group(17). Only twenty European studies combining children and adolescents were identified. They came to diverging conclusions, mainly based on dietary behaviour (e.g. weekly daily breakfast frequency) rather than on quantitative amounts of food eaten. Other recent reviews involving specific food groups or populations gave scattered information, and included only children(Reference Emmett, Jones and Northstone18–Reference Inskip, Baird and Barker20) or else did not make a distinction between children and adolescents(Reference Di Noia and Byrd-Bredbenner21). Overall, maternal education was shown to be a strong determinant of a child’s dietary quality(Reference Emmett, Jones and Northstone18). Lower parental SES has been related to higher consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages (SSB), while children of married couples or cohabitating parents may have lower SSB consumption(Reference Mazarello Paes, Hesketh and O’Malley19). Finally, fruit and vegetable consumption by low-income children differed according to their race/ethnicity(Reference Di Noia and Byrd-Bredbenner21). For the other food groups, available information was insufficient for drawing evidence-based conclusions. And, to our knowledge, no study has specifically focused on diet disparities in young adults.

Education, employment and income, the three components that generally characterise SES in research, are responsible for major health disparities(Reference Glymour, Avendano, Kawachi, Berkman, Kawachi and Glymour22). Although closely related, they are not interchangeable(Reference Galobardes, Lynch and Smith23), and may even influence pathways leading to health inequalities(Reference Glymour, Avendano, Kawachi, Berkman, Kawachi and Glymour22). Moreover, individual characteristics (age, sex, generation, family conditions, etc.) may interact with SES characteristics and should therefore be taken into account so as to better interpret observed gradients(17). Dietary disparities have also been studied via less common indicators, such as place of living, ethnicity and migration background, which were assimilated as socio-economic and cultural indicators(17,Reference Mazarello Paes, Hesketh and O’Malley19) . In addition, nutrition-related characteristics like BMI and physical activity might also be included in statistical modelling that explores diet disparities, but their role in potential over-adjustment needs clarification. Indeed, interrelationships between all these indicators require careful interpretation of observed dietary disparities according to SES characteristics.

However, information available on such disparities during adolescence and early adulthood is scattered. Although conclusions have tended to indicate a social gradient for certain food groups, specificities of life-stage disparities have not been thoroughly addressed and their identification could be relevant for developing targeted interventions. To our knowledge, no recent work has systematically updated available information on diet disparities focusing on adolescence and young adulthood, and oriented towards a wide set of socio-economic factors, including migratory characteristics. The aim of the current systematic review was thus to explore how diet (overall and by food group) differs according to socio-economic and cultural characteristics of adolescents and young adults from high-income countries.

Methods

Search strategy

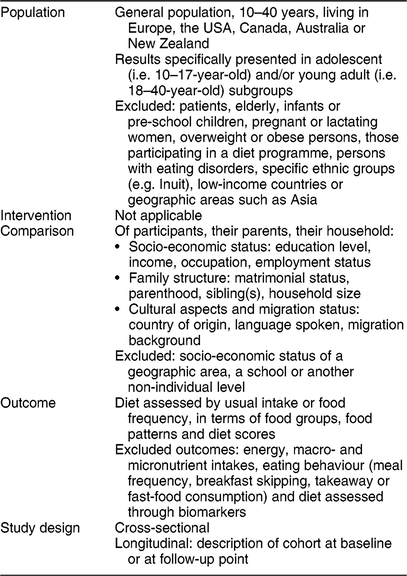

A systematic review of the literature according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines(Reference Moher, Liberati and Tetzlaff24) was conducted between December 2016 and March 2017. Targeted studies sought to examine individual diet according to social, economic and cultural characteristics as their primary or secondary objective. The Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcomes and Study design (PICOS) inclusion and exclusion criteria are presented in Table 1. A relatively large range of ages was targeted (10–40 years) in order to include those studies examining the general population and which analysed subgroups of adolescents and young adults.

Table 1 PICOS (Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcomes and Study design) criteria for inclusion and exclusion of studies in the systematic review

In order to follow up previously published reviews, articles published between 1 January 2012 (the endpoint of the most recently updated review(17)) and 31 March 2017 were searched for in MEDLINE®. A controlled vocabulary from the Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) was used to build a syntax (see online supplementary material) according to keywords encountered in the articles selected in previous works(Reference Darmon and Drewnowski16,17) . MeSH keywords relative to diet were: ‘Diet’, ‘Food’ (without tree explosion), ‘Fruits’, ‘Vegetables’, ‘Dairy Products’, ‘Nutrition surveys’, ‘Feeding behavior’ (without tree explosion), ‘Food preferences’ and ‘Nutrition’. MeSH keywords concerning the social, economic or cultural factors were: ‘Socioeconomic factors’, ‘Risk factors’, ‘Ethnic groups’, ‘Family’, ‘Family characteristics’, ‘Health status’, ‘Human migration’ and ‘Residence characteristics’. Geographic keywords were added: ‘Europe’, ‘Canada’, ‘United States’, ‘Australia’ and ‘New Zealand’. Asia was not included due to specific dietary habits (types of food, dietary patterns). Since recently published articles may not be referenced in MEDLINE according to the MeSH thesaurus, the review was completed by a free search, covering the latest year and using a similar vocabulary. No language restriction was used, so as to obtain a maximum of available information. In fact, no full texts in any language other than English were finally selected. Finally, references cited in literature reviews published on similar topics(Reference Chung, Backholer and Wong15,Reference Emmett, Jones and Northstone18–Reference Di Noia and Byrd-Bredbenner21,Reference Fekete and Weyers25–Reference Zarnowiecki, Dollman and Parletta32) were searched for via MEDLINE, examined and added to the corpus if relevant.

Selection process

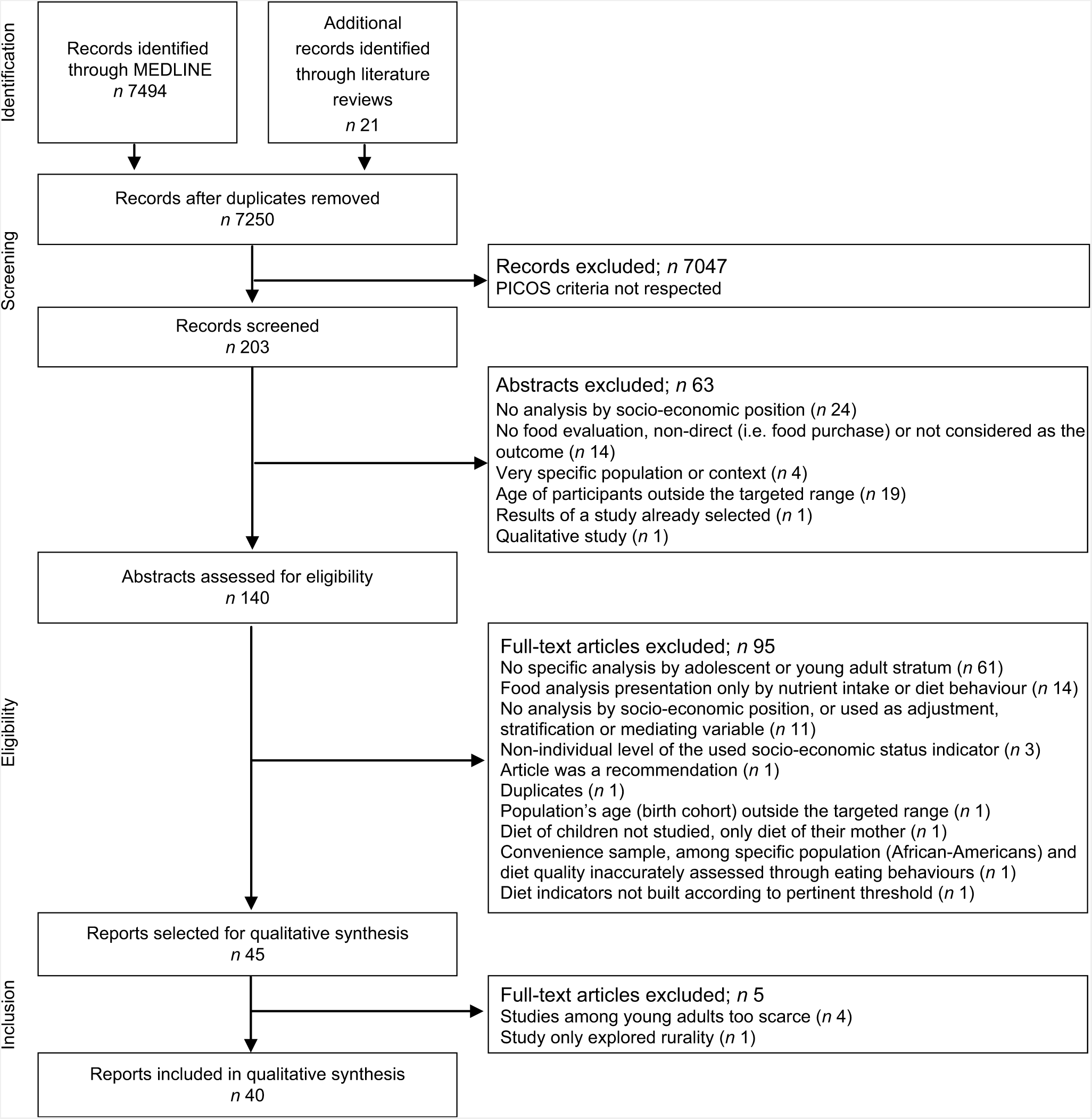

PRISMA guidelines(Reference Moher, Liberati and Tetzlaff24) were used to present the flow selection process (Fig. 1). Titles were independently screened by two investigators, while abstracts and full texts were read by one investigator. All full texts were available through academic resources, except for two, which were obtained after electronic contact with authors.

Fig. 1 Flowchart showing selection of reports included in the systematic review using PRISMA guidelines (PRISMA, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses; PICOS, Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcomes and Study design)

Reasons for record exclusion are presented in the PRISMA flowchart (Fig. 1). Among 140 abstracts assessed for eligibility, ninety-five full texts were excluded: sixty-one because results were not specifically presented for adolescents or young adults, but for a broader age range, and fourteen because diet description covered only nutrients or diet behaviour (e.g. fast foods, breakfast frequency, etc.).

Information was extracted according to a previously established reading grid, which included the following items: name of first author, year of publication, study objectives, country/countries or region, data collection period, study design, sampled population (i.e. national, student, etc.), number of participants included in diet analysis according to socio-economic and cultural factors, age range, diet collection method, diet outcome, socio-economic and cultural status variables, and main results concerning associations between diet and socio-economic or cultural status and adjustment variables.

Quality assessment

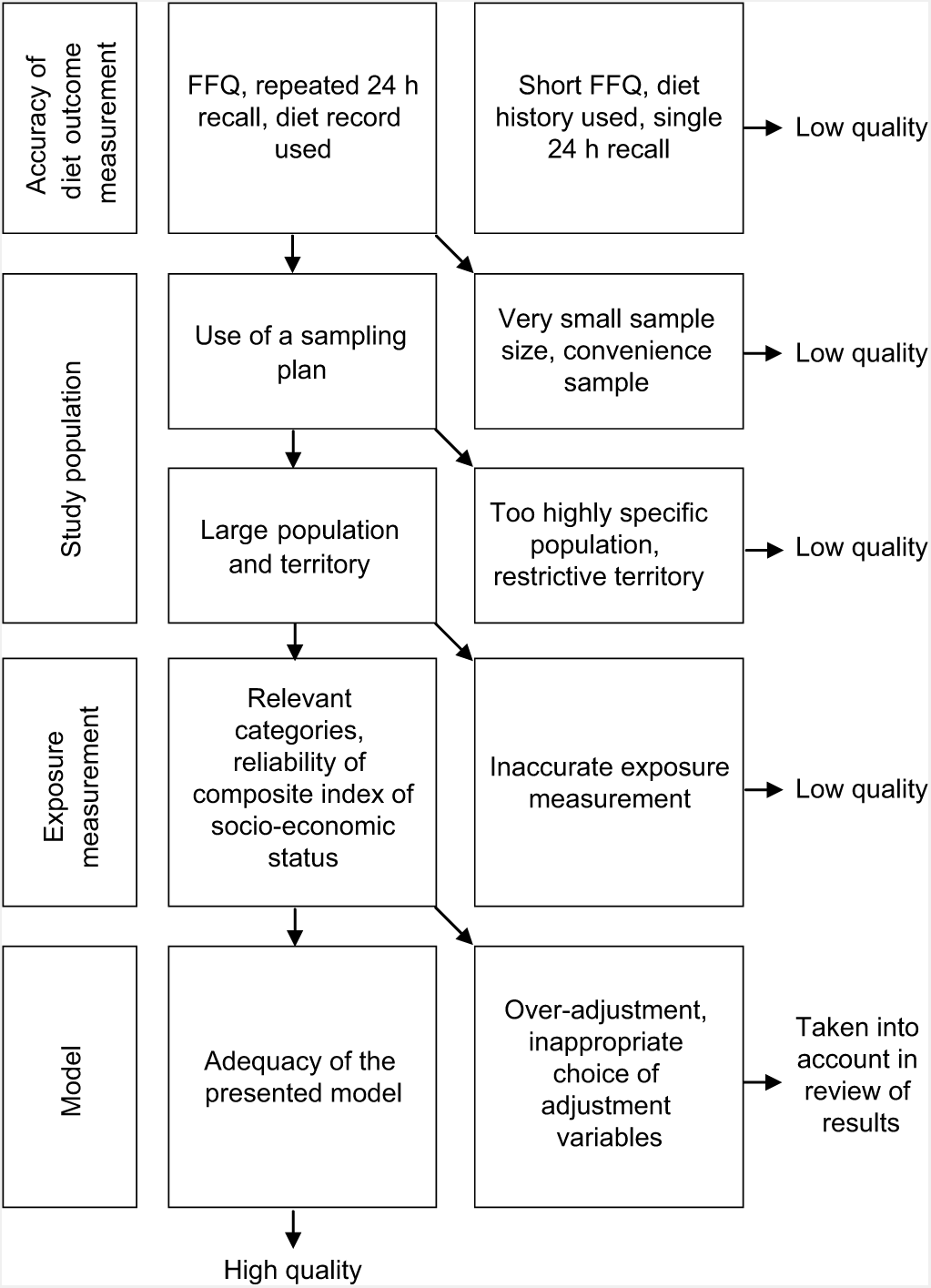

Appropriate methods and the quality of each included study were assessed using a set of criteria (Fig. 2). First, to verify risk of information bias, diet collection methods were examined: repeated 24 h recalls, FFQ including a sufficient number of food items (i.e. at least several tens of items) and diet records were considered a valid method for food intake data collection(Reference Yuan, Spiegelman and Rimm33,Reference Willett34) . Studies based on other types of questionnaires (short FFQ, diet history and single 24 h recall, for example) were considered to be of lesser quality, were not described in detail and were not tabulated.

Fig. 2 Criteria used to assess the methodological quality of studies included in the systematic review

Risk of selection bias was investigated by examining the sampling method; attention was paid primarily to sample size and scope. When a small sample was studied (fewer than 500 participants), or when only a call for volunteers or convenience sampling was used, the quality of the methods was considered ‘low’. Moreover, if the study population was highly specific (e.g. one year of school grade in one city), the study was considered to be of poor quality.

Accuracy of the exposure measurement was then assessed by the relevance of the socio-economic categories chosen (sufficient number of categories making possible a potential gradient, i.e. minimum of three categories, adapted to the population under study) and reliability of the index when such a composite SES was used (e.g. based on both education level and occupation status).

Finally, we focused on analysis modelling, i.e. appropriateness of the final model, and whether potential confounding factors and mediators (i.e. BMI, physical activity, screen time, age, gender, place of living) were identified and accurately integrated into the model. Factors possibly causing confounding results, either concomitant or as mediators in the relationship between SES and diet, are numerous and differently involved depending on the context. Therefore, the objective was to identify potentially over-adjusted models or inappropriate choices of adjustment variables. If no multivariate analysis was found in the article, univariate results were considered, as well as stratification options.

Analysis process

A narrative synthesis, completed by detailed tables, is presented herein. Given the small number and heterogeneity of selected reports, findings concerning young adults (18–40 years old), food groups such as meat, fish and eggs, starchy foods and legumes, water and low-calorie drinks, fat, pulses, nuts and alcoholic drinks, along with disparities according to rural or urban living environment, are not presented.

Results were sorted by type of diet outcome: patterns, diet scores and food groups (vegetables and fruits, dairy foods, SSB, salty and sweet energy-dense foods). For each, socio-economic indicators related to education, occupation, income level, migration status and family structure were presented when available. Names of dietary patterns have been quoted as named in the original articles. Only results of high-quality studies have been detailed in summary tables. Those with lower quality have been added as complementary information in the text. In the tables, studies have been arranged in alphabetical order by first author’s name.

Results

Among 7250 records identified after removing duplicates, forty met inclusion criteria (Fig. 1). Among the forty selected studies, seventeen were considered of satisfactory quality and have been presented in detail and tabulated. The main reason for lower quality was lack of accuracy concerning diet outcome measurement. Indeed, twenty-two studies of poor quality used a short FFQ, a single 24 h recall or dietary history.

Dietary patterns

In total, six reports corresponding to five studies presented a posteriori dietary patterns. Among them, three studies (four reports) were considered of good quality (Table 2) and two of lower quality(Reference Fernandez-Alvira, de Bourdeaudhuij and Singh35,Reference Richter, Heidemann and Schulze36) .

Table 2 Dietary patterns according to socio-economic and cultural characteristics of adolescents* (four reports)

EPITeen, Epidemiological Health Investigation of Teenagers in Porto; ALSPAC, Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children; 24hR, 24 h recall; educ., education; occup., occupation; asso., associated; TV, television; SES, socio-economic status.

* Details on risk of bias assessment are not presented since only studies of good quality are tabulated.

Different categories of dietary patterns were identified and considered according to their potential health benefits or disadvantages. Methods used were cluster analyses(Reference Fernandez-Alvira, de Bourdeaudhuij and Singh35,Reference Araujo, Teixeira and Gaio37–Reference Northstone, Smith and Cribb39) and principal component analyses(Reference Richter, Heidemann and Schulze36,Reference Bibiloni, Martinez and Llull40) . Pattern content varied according to the context. ‘Healthy’(Reference Araujo, Teixeira and Gaio37,Reference Northstone, Smith and Newby38) , ‘Mediterranean’(Reference Bibiloni, Martinez and Llull40), ‘vegetarian’(Reference Northstone, Smith and Cribb39) and ‘dairy product’(Reference Araujo, Teixeira and Gaio37) patterns were identified. Such healthy patterns were confronted with less favourable profiles(Reference Araujo, Teixeira and Gaio37–Reference Northstone, Smith and Cribb39). ‘Western’(Reference Bibiloni, Martinez and Llull40) and ‘traditional’(Reference Northstone, Smith and Newby38) pattern compositions strongly depended on the context: they differed from healthier profiles by their high content in meat, potatoes, bread and cereals, and might also include energy-dense and ultra-processed products. Overlaps between healthy and traditional patterns were also described, creating ‘western and Mediterranean’(Reference Bibiloni, Martinez and Llull40) and ‘traditional/health conscious’(Reference Northstone, Smith and Cribb39) patterns, with the latter considered as ‘fairly healthy’.

Among the four dietary pattern studies of good quality (Table 2), in three out of three studies examining education level, patterns considered as healthy were associated with higher parental education levels, especially maternal(Reference Araujo, Teixeira and Gaio37,Reference Northstone, Smith and Cribb39) , for girls only in one study(Reference Bibiloni, Martinez and Llull40). In three out of these three studies analysing occupation, healthy patterns were related to higher parental occupation position(Reference Araujo, Teixeira and Gaio37), in girls only in one study(Reference Bibiloni, Martinez and Llull40), and were observed more frequently when the adolescents’ mothers were unemployed, in comparison to working mothers in a third study(Reference Northstone, Smith and Cribb39). In all these studies, less favourable patterns were associated with lower parental education(Reference Araujo, Teixeira and Gaio37,Reference Northstone, Smith and Cribb39) (in girls only in one study)(Reference Bibiloni, Martinez and Llull40). The ‘western’ profile was related to a lower parental occupation(Reference Bibiloni, Martinez and Llull40), and ‘snacks/sugared drinks’ were more frequent among working mothers of adolescents(Reference Northstone, Smith and Cribb39). Moreover in a fourth study, tracking of healthy or unfavourable patterns at three time points was correlated with higher and lower maternal education level, respectively(Reference Northstone, Smith and Newby38). Results were consistent in studies using less accurate diet measurement methods(Reference Fernandez-Alvira, de Bourdeaudhuij and Singh35,Reference Richter, Heidemann and Schulze36) , but slightly discordant when the SES index based on parental education, occupation and income was examined in Germany: the ‘western’ pattern was associated with higher parental SES, while the reverse was observed for the ‘traditional and western’ profile(Reference Richter, Heidemann and Schulze36).

Ethnicity was explored in the Avon area of the UK at 13-year follow-up(Reference Northstone, Smith and Cribb39): the ‘vegetarian’ pattern was associated with being ‘non-white’ in comparison with the ‘white’ group in this predominantly white population. On the other hand, the unfavourable ‘snacks and sugared drinks’ profile was more frequent among white than among non-white adolescents. Nevertheless, non-white adolescents were more likely to remain in the ‘processed’ pattern when they were tracked over time, according to a second report concerning the same cohort(Reference Northstone, Smith and Newby38). Finally, in one study regarding family structure indicators, ‘snacks and sugared drinks’ and ‘processed’ patterns were pointed out as being more frequent in families with more siblings(Reference Northstone, Smith and Cribb39).

Scores

Eleven selected reports, corresponding to ten studies, analysed a priori diet scores in adolescent populations. Five studies (six reports) were considered of good quality (Table 3) and five of lower quality, and were not tabulated(Reference Arriscado, Muros and Zabala41–Reference Papadaki and Mavrikaki45). One study (two reports) of good quality was conducted in low-socio-economic areas(Reference Kastorini, Lykou and Yannakoulia46,Reference Yannakoulia, Lykou and Kastorini47) .

Table 3 Diet scores according to socio-economic or cultural characteristics of adolescents* (six reports)

HELENA, Healthy Lifestyle in Europe by Nutrition in Adolescence; KiGGs, German Health Interview and Examination Survey for Children and Adolescents; 24hR, 24 h recall; DQI-AM, Diet Quality Index for Adolescents; HuSKY, Healthy Nutrition Score for Children and Youth; KIDMED, Mediterranean Diet Quality Index for Children and Adolescents; educ., education; occup., occupation; SES, socio-economic status; FAS, Family Affluence Scale; asso., associated.

* Details on risk of bias assessment are not presented since only studies of good quality are tabulated.

Different types of scores adapted to adolescents were used, measuring the compliance with a nationally recommended diet(Reference Martin, van Hook and Quiros44,Reference Beghin, Dauchet and de Vriendt48,Reference Finger, Varnaccia and Tylleskar49) or to a Mediterranean diet(Reference Kastorini, Lykou and Yannakoulia46,Reference Yannakoulia, Lykou and Kastorini47,Reference Grosso, Marventano and Buscemi50,Reference Ozen, Bibiloni and Murcia51) . All these scores were calculated from consumed amounts of several predefined food groups, ranging from seven to sixteen groups. The Diet Quality Index for Adolescents was used in one study(Reference Beghin, Dauchet and de Vriendt48): in addition to compliance with recommendations, this score takes into account diet diversity, dietary balance and meal frequency.

Among studies of good quality (Table 3), in five out of five studies, the diet score of adolescents was higher when the parental education level was higher(Reference Beghin, Dauchet and de Vriendt48,Reference Finger, Varnaccia and Tylleskar49) , especially maternal education(Reference Kastorini, Lykou and Yannakoulia46,Reference Yannakoulia, Lykou and Kastorini47,Reference Ozen, Bibiloni and Murcia51) . A similar trend according to parental occupation was observed in two out of three studies(Reference Beghin, Dauchet and de Vriendt48,Reference Ozen, Bibiloni and Murcia51) , while occupation was not significantly associated in the third(Reference Finger, Varnaccia and Tylleskar49). In addition, the diet score was higher when the SES index based on parental education and occupation was higher in the only study that explored such an index(Reference Grosso, Marventano and Buscemi50). The relationship of diet with income was explored in three studies: among students in Greek areas with low SES, adherence to a Mediterranean diet was positively associated with family affluence(Reference Yannakoulia, Lykou and Kastorini47) and was higher when the father had an income(Reference Kastorini, Lykou and Yannakoulia46). Household income was not associated with diet score in the third study(Reference Finger, Varnaccia and Tylleskar49).

In the high-quality study examining migration among Greek students attending schools from low-SES areas, adherence to a Mediterranean diet was higher if the mother was a native Greek(Reference Kastorini, Lykou and Yannakoulia46). Similar trends were pointed out in two studies of lesser quality, showing healthier diet when participants were natives compared with migrants(Reference Arriscado, Muros and Zabala41) and when they were first- or second-generation migrants compared with the third generation(Reference Martin, van Hook and Quiros44).

Food groups

Twenty-six selected reports, corresponding to twenty-two different studies, described adolescent diets using food groups. Eight studies (nine reports) were considered of good quality (Tables 4–7), including five reports that focused on one or several specific food groups(Reference Finger, Varnaccia and Tylleskar49,Reference Drewnowski and Rehm52–Reference Lehto, Ray and Te Velde55) and four reports that covered almost all main food groups and subgroups(Reference Grosso, Marventano and Buscemi50,Reference Drouillet-Pinard, Dubuisson and Bordes56–Reference Llull, Bibiloni and Pons58) . The other fourteen studies (seventeen reports) were considered of lower quality(Reference Arriscado, Muros and Zabala41,Reference Kakinami, Gauvin and Seguin59–Reference Larson, Story and Eisenberg74) .

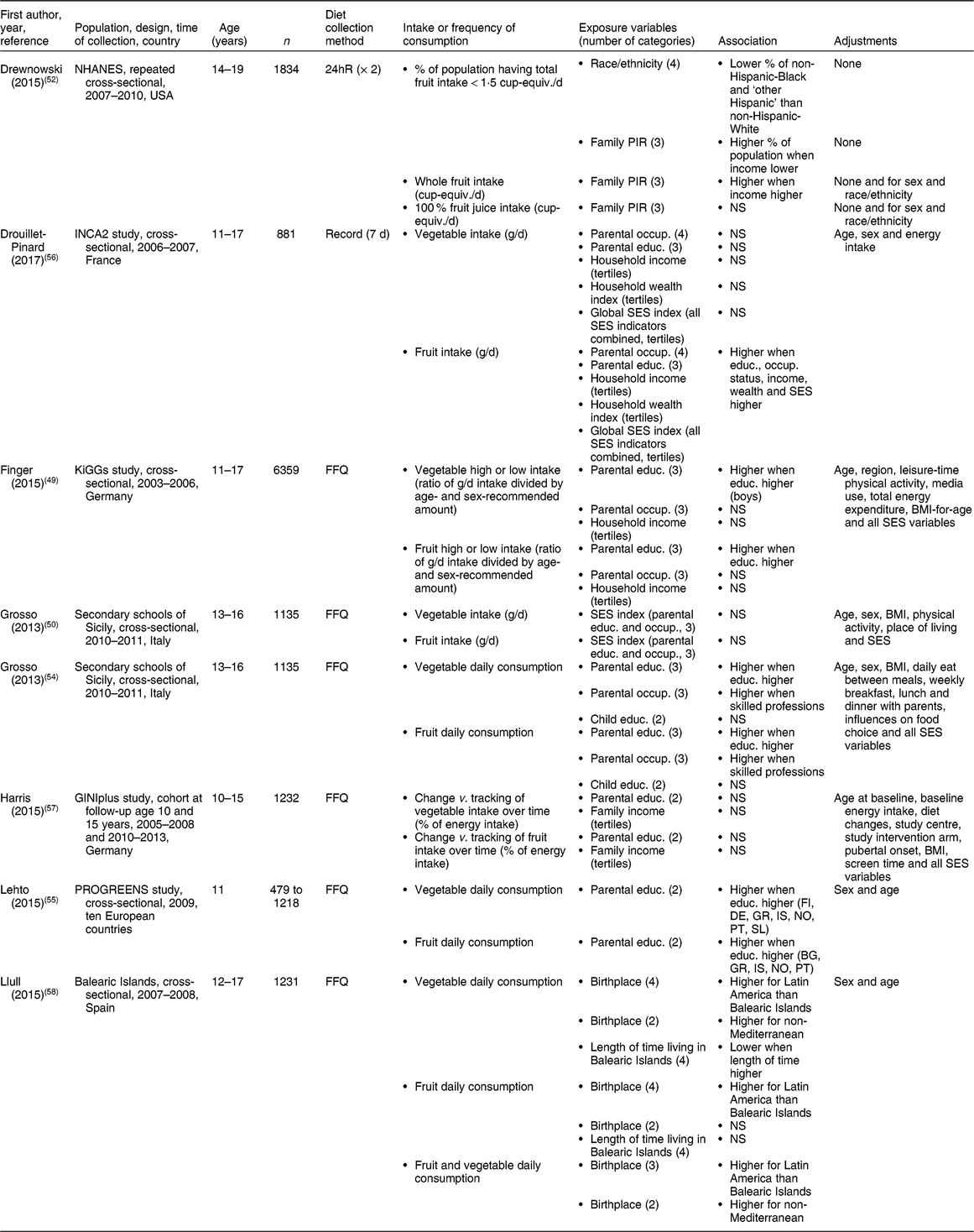

Table 4 Vegetable and fruit consumptions according to socio-economic or cultural characteristics of adolescents* (eight reports)

NHANES, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey; INCA2, second French national cross-sectional dietary survey; KiGGs, German Health Interview and Examination Survey for Children and Adolescents; 24hR, 24 h recall; equiv., equivalents, PIR, poverty income ratio; occup., occupation; educ., education; SES, socio-economic status; FI, Finland; DE, Germany; GR, Greece; IS, Iceland; NO, Norway; PT, Portugal; SL, Slovenia; BG, Bulgaria.

* Details on risk of bias assessment are not presented since only studies of good quality are tabulated.

Fruits and vegetables

The ‘vegetable’ group was not defined in most reports(Reference Grosso, Marventano and Buscemi50,Reference Grosso, Marventano and Nolfo54,Reference Drouillet-Pinard, Dubuisson and Bordes56–Reference Llull, Bibiloni and Pons58) ; in others(Reference Finger, Varnaccia and Tylleskar49,Reference Lehto, Ray and Te Velde55) , it was composed of raw, frozen, canned and cooked vegetables. The ‘fruit’ group composition was less homogeneous: some included 100 % fruit juice(Reference Drouillet-Pinard, Dubuisson and Bordes56), all types of fruit juice(Reference Llull, Bibiloni and Pons58), dried fruits(Reference Drouillet-Pinard, Dubuisson and Bordes56) or only fresh(Reference Finger, Varnaccia and Tylleskar49) or whole fruits(Reference Harris, Flexeder and Thiering57), while some did not define composition(Reference Grosso, Marventano and Buscemi50,Reference Grosso, Marventano and Nolfo54,Reference Lehto, Ray and Te Velde55) . One report showed analyses of grouped fruits and vegetables(Reference Llull, Bibiloni and Pons58). Fruit and vegetable consumption was generally higher when SES indicators were more favourable and none of the selected studies showed an inverse association (Table 4).

Four studies of good quality analysed the association between parental education and vegetable intake. In two studies, and after various adjustments, adolescents with more highly educated parents daily consumed more vegetables(Reference Grosso, Marventano and Nolfo54,Reference Lehto, Ray and Te Velde55) . In one study, vegetable intake did not vary according to parental education level after adjustment for sex, age and energy intake(Reference Drouillet-Pinard, Dubuisson and Bordes56). Nevertheless, in the fourth study, the highest intake category was associated with higher parental education for boys, after adjustment for sex- and age-recommended amounts of vegetables(Reference Finger, Varnaccia and Tylleskar49). In addition, these four studies all showed higher fruit intake and daily consumption when parental education was higher(Reference Finger, Varnaccia and Tylleskar49,Reference Grosso, Marventano and Nolfo54–Reference Drouillet-Pinard, Dubuisson and Bordes56) . Moreover, studies of lower quality showed positive associations between parental education and fruit and vegetable consumption frequency(Reference Ahmadi, Black and Velazquez60,Reference Pitel, Madarasova Geckova and Reijneveld67) .

Two studies investigated the association between vegetable intake and household income/wealth, but found no statistical association(Reference Finger, Varnaccia and Tylleskar49,Reference Drouillet-Pinard, Dubuisson and Bordes56) . In one of three studies investigating fruit consumption, daily fruit intake was higher when household income and wealth levels were higher, after adjustment for age, sex and energy intake in one study(Reference Drouillet-Pinard, Dubuisson and Bordes56), whereas in another study(Reference Finger, Varnaccia and Tylleskar49) dichotomized fruit intake was not associated with household income after various adjustments. In a third study, total and whole fruit intake was higher when the family income-to-poverty ratio was higher, whereas 100 % fruit juice intake was not associated with family income(Reference Drewnowski and Rehm52). In five out of seven lower-quality studies of fruit and vegetable consumption according to the Family Affluence Scale (FAS) or food insecurity, higher daily consumption was associated with higher FAS(Reference Fismen, Smith and Torsheim61,Reference Fismen, Smith and Torsheim62,Reference Moore and Littlecott65,Reference Voracova, Sigmund and Sigmundova70,Reference Attorp, Scott and Yew71) . Another of these studies also showed that adolescents with a decreasing or increasing poverty level over time consumed less fruits and vegetables than adolescents with a stable non-poor trajectory(Reference Kakinami, Gauvin and Seguin59).

Vegetable intake was not associated with parental occupation in two studies(Reference Finger, Varnaccia and Tylleskar49,Reference Drouillet-Pinard, Dubuisson and Bordes56) , but in one of these(Reference Drouillet-Pinard, Dubuisson and Bordes56), fruit intake was higher when parental occupational status was higher. Higher daily consumption of vegetables and fruits was associated with parental skilled professions, after various adjustments(Reference Grosso, Marventano and Nolfo54). Moreover, fruit intake was higher when the global SES index was higher in one study(Reference Drouillet-Pinard, Dubuisson and Bordes56), while it was not associated in another(Reference Grosso, Marventano and Buscemi50). Vegetable intake was not associated with the overall SES level in these two studies.

Nor was there an association of tracking or change in vegetable and fruit intake over time with parental education or family income in the only study that examined this aspect(Reference Harris, Flexeder and Thiering57).

For sociocultural characteristics, fruit and vegetable consumption differed according to birthplace(Reference Llull, Bibiloni and Pons58) and ethnic origins(Reference Drewnowski and Rehm52) highly specific to each study context. The first study showed that fruit and vegetable consumption was generally higher for migrants from distant countries and more recent migrants than for natives(Reference Llull, Bibiloni and Pons58). In a US sample in the second study, a lower proportion of non-Hispanic Blacks and ‘other Hispanics’ daily consumed smaller amounts of total fruits than non-Hispanic Whites(Reference Drewnowski and Rehm52). In three out four studies of lower quality, consumption of fruits and vegetables also differed according to migration status(Reference Arriscado, Muros and Zabala41) and ethnic origin(Reference Meijerink, van Vuuren and Wijnhoven63,Reference Dodd, Briefel and Cabili72) .

Dairy

Most reports defined the ‘dairy’ group as being composed of milk, yoghurt and cheese(Reference Grosso, Marventano and Buscemi50,Reference Harris, Flexeder and Thiering57,Reference Llull, Bibiloni and Pons58) . Some reports also included dairy drinks(Reference Drouillet-Pinard, Dubuisson and Bordes56), flavoured milk, smoothies and milkshakes(Reference Gopinath, Flood and Burlutsky53) in this group. Some studies indicated higher dairy intake associated with more favourable SES, but overall findings were not consistent (Table 5). Among three studies, one showed that yoghurt intake was higher when parental education, income, wealth and overall SES index were higher, after adjusting for age, sex and energy intake(Reference Drouillet-Pinard, Dubuisson and Bordes56). However, in that study, the studied dairy product intake was never associated with parental occupation, and milk and cheese consumption were not associated with any SES indicator. In the other two studies, dairy intake was higher when parents had tertiary qualifications, but was not associated with occupation(Reference Gopinath, Flood and Burlutsky53) or SES index (parental occupation and education levels)(Reference Grosso, Marventano and Buscemi50). Neither changing nor tracking dairy intake over time was associated with parental education or income in the only study concerned(Reference Harris, Flexeder and Thiering57).

Table 5 Dairy food consumption according to socio-economic or cultural characteristics of adolescents* (five reports)

INCA2, second French national cross-sectional dietary survey; occup., occupation; educ., education; SES, socio-economic status.

* Details on risk of bias assessment are not presented since only studies of good quality are tabulated.

Neither of two studies examining the association between dairy consumption and ethnicity showed a significant association(Reference Gopinath, Flood and Burlutsky53,Reference Llull, Bibiloni and Pons58) . Among two studies of lesser quality, one described higher consumption of dairy products for breakfast among Spanish adolescents than among other nationalities(Reference Arriscado, Muros and Zabala41). The other described a proportion of adolescents consuming whole or skimmed milk that differed according to ethnicity, with fewer non-Hispanic Blacks consuming such dairy products(Reference Dodd, Briefel and Cabili72).

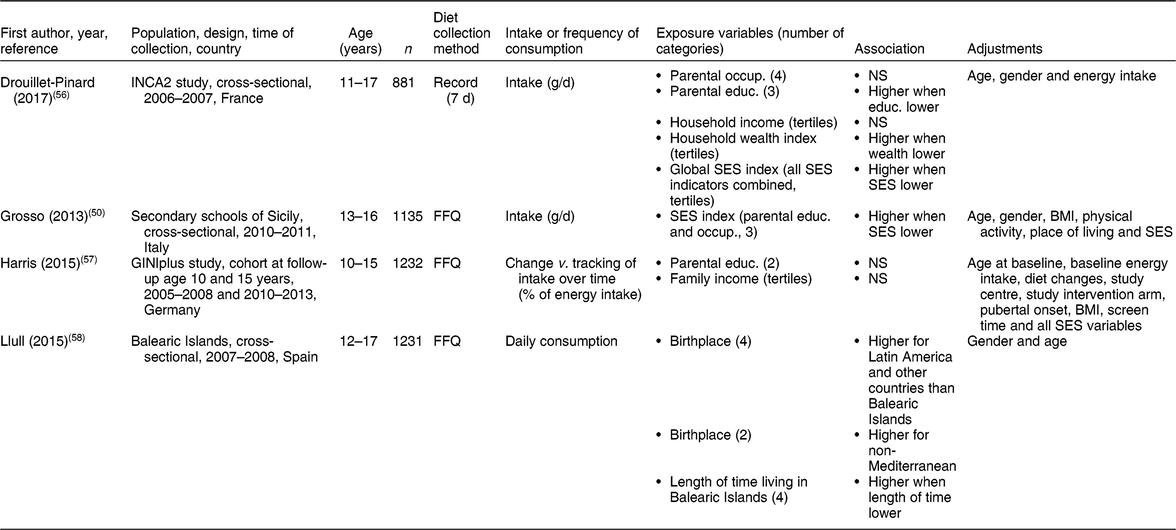

Sugar-sweetened beverages

The SSB group was defined throughout the reports as sugary, soft and diet drinks(Reference Grosso, Marventano and Buscemi50,Reference Drouillet-Pinard, Dubuisson and Bordes56,Reference Llull, Bibiloni and Pons58) . In one study, it was also composed of fruit and vegetable juices(Reference Harris, Flexeder and Thiering57). SSB drinking, explored in two studies, was higher when parental education(Reference Grosso, Marventano and Buscemi50,Reference Drouillet-Pinard, Dubuisson and Bordes56) , household wealth(Reference Drouillet-Pinard, Dubuisson and Bordes56) and global SES(Reference Drouillet-Pinard, Dubuisson and Bordes56) were lower, after various adjustments (Table 6). However, SSB intake was not associated with parental occupation or household income(Reference Drouillet-Pinard, Dubuisson and Bordes56). Four out of five studies of lower quality were rather consistent with each other, showing more frequent SSB consumption when parental education(Reference Ahmadi, Black and Velazquez60) and FAS(Reference Fismen, Smith and Torsheim62) were lower and when poverty level indicators were higher.

Table 6 Sugar-sweetened beverage consumption according to socio-economic or cultural characteristics of adolescents* (four reports)

INCA2, second French national cross-sectional dietary survey; occup., occupation; educ., education; SES, socio-economic status.

* Details on risk of bias assessment are not presented since only studies of good quality are tabulated.

One study carried out in the Balearic Islands explored diet according to birthplace. SSB consumption was higher for adolescents born in Latin America and other foreign countries than for natives, and also higher for those of non-Mediterranean than of Mediterranean origin(Reference Llull, Bibiloni and Pons58). Moreover, it was higher when the length of time living in the Balearic Islands was lower. Three out of four lower-quality studies showed significant differences between ethnic groups(Reference Richmond, Spadano-Gasbarro and Walls68,Reference Sundborn, Utter and Teevale69,Reference Larson, Story and Eisenberg74) .

Change in or tracking of SSB intake over time was not associated with parental education or family income(Reference Harris, Flexeder and Thiering57). A lower-quality study of SSB intake decline over time reported differences according to ethnicity, but this was not statistically tested(Reference Bleich and Wolfson73).

Salty and sweet energy-dense foods

In this group, studies included informal meals generally composed of fatty, salty and sweet snacks and fast foods, without defining a threshold of energy density. Other studies also included soft drinks(Reference Finger, Varnaccia and Tylleskar49) or stewed fruits and fruits in syrup(Reference Drouillet-Pinard, Dubuisson and Bordes56). One study focused only on sweet and fatty snacks(Reference Harris, Flexeder and Thiering57), and another on sweets and pastries(Reference Llull, Bibiloni and Pons58). Amounts of energy-dense foods consumed by adolescents were globally higher when socio-economic characteristics were less favourable, but such findings were not systematically retrieved (Table 7). Two studies out of three showed higher intake when parental education(Reference Finger, Varnaccia and Tylleskar49,Reference Drouillet-Pinard, Dubuisson and Bordes56) , occupation(Reference Finger, Varnaccia and Tylleskar49,Reference Drouillet-Pinard, Dubuisson and Bordes56) and household income and wealth(Reference Finger, Varnaccia and Tylleskar49,Reference Drouillet-Pinard, Dubuisson and Bordes56) were lower, after various adjustments. However, an exception was seen: cake and pastry intake was lower when occupational status and global SES were lower(Reference Drouillet-Pinard, Dubuisson and Bordes56). Intakes of stewed fruits, fruits in syrup, confectionery, pizza, sandwiches, fast foods and sweets were otherwise not associated with SES-related indicators(Reference Grosso, Marventano and Buscemi50,Reference Drouillet-Pinard, Dubuisson and Bordes56) . Studies of lower quality mainly showed higher consumption of sweets when FAS(Reference Fismen, Smith and Torsheim62,Reference Voracova, Sigmund and Sigmundova70) and parental education(Reference Pitel, Madarasova Geckova and Reijneveld67) were lower, and higher daily consumption of energy-dense and nutrient-poor snacks when SES was lower, but such associations were not statistically tested(Reference Larson, Story and Eisenberg74).

Table 7 Salty and sweet energy-dense food consumption according to socio-economic or cultural characteristics of adolescents* (five reports)

INCA2, second French national cross-sectional dietary survey; KiGGs, German Health Interview and Examination Survey for Children and Adolescents; occup., occupation; educ., education; SES, socio-economic status.

* Details on risk of bias assessment are not presented since only studies of good quality are tabulated.

Only one study in the Balearic Islands explored the associations according to birthplace. Latin American and, more generally, non-Mediterranean adolescents had higher sweets consumption than natives, and sweets and pastry consumption was higher when the length of time living on the Balearic Islands was lower(Reference Llull, Bibiloni and Pons58). One study of lesser quality showed higher sweets and fast-food consumption among adolescents of nationalities other than Spanish(Reference Arriscado, Muros and Zabala41).

Change in or tracking of sugar-sweetened food intake over time was not associated with education or income(Reference Harris, Flexeder and Thiering57). A decline in sweet and salty snack intake over time was observed among Black adolescents with a healthy weight, but ethnic differences were not tested in that study(Reference Bleich and Wolfson73).

Discussion

Our objective was to update overall knowledge of socio-economic and cultural disparities in dietary patterns, scores and food group consumption by adolescents and young adults. Recent literature on diet disparities has been abundant, but when focusing on this life period, the quality of the studies appears highly variable and available information is scattered. Among adolescents, however, evidence and consistent findings were sufficient to conclude that higher dietary scores and healthier patterns were associated with higher parental education and occupational status, while less favourable patterns were associated with lower SES. Such findings therefore confirmed, at least in part, that a favourable social status is generally associated with a healthier diet.

Regarding food groups, the most substantial bibliographic corpus concerned fruits and vegetables. Such consumption was consistently associated with higher education. In addition, fruit consumption was somewhat higher when household income and wealth were higher. Despite a smaller number of conclusive high-quality studies, SSB, energy-dense food and dairy product consumption were globally associated with SES: SSB and energy-dense food consumption were higher when SES indicators were less favourable, while dairy intake tended to be higher when SES was more favourable. However, available information regarding other groups was very scarce. In addition to SES-related indicators, ethnic and migration disparities were pointed out in several studies but proved to be highly specific to each country and geographic area.

Overall, conclusions are limited due to the heterogeneity of the populations, diet outcome and socio-economic and cultural indicators in question. Thus, it would not have been feasible to carry out a meta-analysis, nor to explore potential publication bias. Moreover, use of a quantitative scale assessing methodological quality would have been too restrictive. Nevertheless, quality assessment was used, making possible a selection based on objective criteria adapted to the diversity of the publications.

Diversity of methods

Most studies using scores were adapted to recommendations dedicated to adolescents, leading to conclusions that could be compared. Since they depended on the population and context of the study, dietary patterns differed from one study to another, making findings between some countries not directly comparable. However, consistent conclusions were generally drawn. The advantage of describing disparities according to food groups lies in being able to identify specific associated indicators. Food choice and consumption mechanisms may also differ according to food group(Reference Darmon and Drewnowski16). The issue is to consequently adapt dietary recommendations based on such findings. However, diet collection and description methods differed across studies and thus, for some food groups, it was difficult to draw conclusions.

Statistical models and adjustments were highly variable between studies. Adjustments for sex, age and total energy intake (scores, food groups) enabled taking account of differences in requirements. BMI was sometimes used as an adjustment variable, limiting interpretation, since it may be both a consequence of an unhealthy diet and a reason for adopting a balanced diet. Some authors also chose to adjust for other nutrition-related behaviour (e.g. physical activity, screen time) in order to identify potential confounders, and thus over-adjustment was probable. In some models, identification of the true role of adjustment variables was challenging. Nutrition-related behaviour variables may have been mediators, logically weakening the association between SES and diet. Some adjustment variables were also presented as confounding factors; however, although they were influenced by SES, they could not substitute for that variable in the relationship with diet.

Mechanisms of disparities

Dietary disparities among adolescents overwhelmingly involved inequalities in parental education, particularly maternal. Education is linked to health literacy, i.e. the ability to appropriate health and nutrition information and to generate dietary behaviour that would provide long-term benefits(Reference Galobardes, Shaw and Lawlor75). However, occupation and income were not systematically associated with diet. Income is directly related to financial accessibility to food, and occupation may influence food intake partly via the workplace culture and social networks(Reference Galobardes, Morabia and Bernstein76). Moreover, it has been clearly established that education is a determinant of occupation and income, and that these three indicators are involved in diet disparities, but differently, according to the SES indicator(Reference Darmon and Drewnowski16,Reference Méjean, Si Hassen and Lecossais77,Reference Si Hassen, Castetbon and Cardon78) . In addition, reliability and availability of some SES indicators were insufficient to draw clear conclusions. Nevertheless, the present review shows that parental education was a more systematic determinant of diet than occupation or income. In terms of public health policies, it again emphasizes that nutritional information should be adapted to different education backgrounds and integrated into early education, targeting mothers or caregivers.

According to the food group in question: (i) either all socio-economic indicators were associated (e.g. fruits); (ii) only some SES characteristics were associated (e.g. vegetables, dairy, SSB); or (iii) these associations were contradictory (e.g. in the case of energy-dense foods). Such disparities within a food group have been described previously; authors have suggested exploring causal mechanisms involved, such as biological (possibly related to higher palatability and lower satiety provided by such energy-dense foods) or behavioural components (accessibility and affordability)(Reference Darmon and Drewnowski16). For instance, SSB consumption was determined by lower parental financial status (along with less schooling). Indeed, SSB are financially and physically accessible products, often associated with positive values through sports marketing, on the one hand, and time spent in front of screens and sedentary behaviour, on the other(Reference Mazarello Paes, Hesketh and O’Malley19).

In addition to the main SES indicators, ethnicity and migration status were often associated with diet, but findings appeared to be related to the general background. In some studies carried out in the USA(Reference Drewnowski and Rehm52,Reference Dodd, Briefel and Cabili72) , Australia(Reference Gopinath, Flood and Burlutsky53) and the UK(Reference Northstone, Smith and Newby38,Reference Northstone, Smith and Cribb39) , ethnicity was explored mainly as a reflection of SES. In other Mediterranean(Reference Kastorini, Lykou and Yannakoulia46,Reference Llull, Bibiloni and Pons58) , American(Reference Martin, van Hook and Quiros44) and Canadian(Reference Attorp, Scott and Yew71) studies, parental place of birth, migratory generation and length of time living in the host country were studied. The migration background was thus also explored under the angle of dietary habit acquisition and acculturation(Reference Brown, Houser and Mattei79–Reference Osei-Kwasi, Powell and Nicolaou81). For instance, in the general adolescent Balearic Islands population, it was difficult to distinguish effects related to acculturation from those related to SES, since SES indicators were not examined(Reference Llull, Bibiloni and Pons58). Nevertheless, higher consumption of SSB and energy-dense foods in recent adolescent migrants may be due to their increased accessibility; furthermore, higher vegetable consumption may be related to culture-specific dietary habits. In addition, variations according to country of origin and stage of nutritional transition should be taken into account.

Conclusions

Based on the present review, findings on dietary patterns and scores, along with fruit and vegetable consumption in adolescents, consistently confirmed the socio-economic gradient observed in adults. However, overall conclusions were much more limited for several food groups and warrant further examination. In addition, high-quality studies remain necessary, especially in terms of reliable dietary and socio-economic evaluations. Sampling of both the general adolescent population and potentially at-risk subgroups such as migrants should also be more carefully examined. Finally, diet in young adults has thus far been poorly described and needs to be concomitantly evaluated so as to improve our understanding of changes in socio-economic and cultural disparities during this transition period.

Nevertheless, the present review, consistent with wide dietary disparities among adolescents, underlines the importance of developing interventions targeted to this age group. Future public health programmes must take the socio-economic gap into account, addressing nutritional intervention towards both populations as a whole, with the most vulnerable being the adolescent population. Indeed, such initiatives should seek to improve literacy by involving caregivers and taking account of the migration background and associated food culture. Although its long-term sustainability requires confirmation, an improvement in dietary habits during adolescence may continue into adulthood and could contribute to a reduction in non-communicable disease inequalities.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: The authors thank Valérie Durieux for her technical guidance on the literature search and Jerri Bram for English editing. Financial support: This work was supported by the French Community of Belgium, as part of the ‘Actions de Recherche Concertée’ funding programme. The French Community of Belgium had no role in the design, analysis or writing of this article. Conflict of interest: None. Authorship: L.D. and K.C. formulated the research question and designed the study; L.D. carried out the research; L.D. and K.C. analysed the data; L.D. wrote the paper; K.C., C.M. and S.D.H. edited the article. Ethics of human subject participation: Not applicable.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980019002362.