Maintaining healthy dietary behaviours is crucial for population health and the prevention of non-communicable disease. The most recent statistics show that there are around 850 000 people in the UK with dementia.(1) The number of people with dementia is increasing because people are living longer with estimations showing that by 2025, the number of people with dementia in the UK will have increased to around 1 million(1). It is estimated that by 2025, 20 % of the population will be over 65 years and, with this increased longevity, there is a need to identify potential variables such as diet to promote healthy ageing.

Many of the epidemiological studies of dietary patterns have investigated the impact of the Mediterranean diet and the DASH diet (Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension)(Reference Sacks, Appel and Moore2) on cognitive function(Reference Morris3). Research found that higher adherence to the respective diets was significantly associated with less cognitive decline in midlife over a 4-month period(Reference Smith, Blumenthal and Babyak4) and also in older adults over a 4-year period(Reference Tangney, Li and Wang5).

The MIND diet (Mediterranean-DASH Intervention for Neurodegenerative Delay)(Reference Morris, Tangney and Wang6) is a hybrid of the Mediterranean diet(Reference Panagiotakos, Pitsavos and Stefanadis7) and DASH diet. Findings from research on the Mediterranean and DASH diets suggest they may have protective effects on cardiovascular conditions that may adversely affect brain health(Reference Morris, Tangney and Wang6). Therefore, the MIND diet was designed to emphasise the dietary components and servings linked to neuroprotection and dementia prevention(Reference Morris, Tangney and Wang6). The MIND diet consists of ten healthy foods (leafy greens, other vegetables, nuts, berries, fish, poultry, olive oil, beans, whole grains and red wine) and five other foods which are to be limited (red meat, butter, cheese, pastries and sweets, and fried foods).

There has been limited research investigating the MIND diet; however, recent research with older adults found that the MIND diet can slow cognitive decline over an average of 4·7 years(Reference Morris, Wang and Tangney8). This study found that the MIND diet score was more predictive of cognitive decline than either the Mediterranean diet or DASH diet. Research found a 53 % lower risk for Alzheimer’s disease with high adherence to the MIND diet(Reference Morris, Wang and Tangney8). Furthermore, a 35 % lower risk of Alzheimer’s disease was shown for a moderate adherence to the MIND diet(Reference Morris, Wang and Tangney8), whereas no significant association with Alzheimer’s disease was shown for the Mediterranean or DASH diet(Reference Van den Brink, Brouwer-Brolsma and Berendsen9). Further support for a lower risk of cognitive decline with both moderate and high adherence to the MIND diet is shown in Adjibade et al. (2019). This study showed that 72 % of the large sample (6011) adhered at least moderately to the MIND diet(Reference Adjibabe, Assmann and Julia10). Interestingly, recent research found that the MIND diet and not the Mediterranean diet protected against 12-year incidence of mild cognitive impairment and dementia in older adults(Reference Hosking, Eramudugolla and Cherbuin11). A longitudinal study with older adults found that higher adherence to the MIND diet was associated with less cognitive decline after a 6-year follow-up(Reference Shakersain, Rizzuto and Larrsson12) and that greater long-term adherence to the MIND diet was associated with better verbal memory over 6 years in older adults(Reference Berendsen, Feskens and de Groot13).

Little is known about the social, environmental and cultural perspectives of adopting the MIND diet in the UK. However, research has found that adopting a Mediterranean style diet has social, cultural and environmental barriers. Research found that participants reported British culture to be non-conducive to a Mediterranean dietary pattern(Reference Middleton, Smith and Keegan14) and that factors such as time, work and convenience were barriers to consuming a Mediterranean style diet(Reference Pinho, Mackenbach and Charreire15,Reference Nicholls, Perry and Pierce16) . The cost of food is suggested to play a role in peoples food choices(Reference Kearney, Kearney and Gibney17) and that a healthy diet may be costlier than a less healthy diet(Reference Conklin, Monsivais and Wareham18,Reference Rao, Afshin and Singh19) . Therefore, budget could be a barrier to eating a Mediterranean style diet, especially for those of low socio-economic status. However, previous research has found that while consuming a healthier diet such as increasing fruit and vegetables may be more expensive, this cost could be offset with the reduction in meat product cost(Reference Kretowicz, Hundley and Tsofliou20).

This study seeks to explore the perceived barriers and facilitators to adopting the MIND diet at midlife (40–55 years) in this non-Mediterranean country. This research could also add support to the dementia strategy research by exploring modifiable risk factors in the prevention of dementia, which could be applied globally.

Theoretical framework

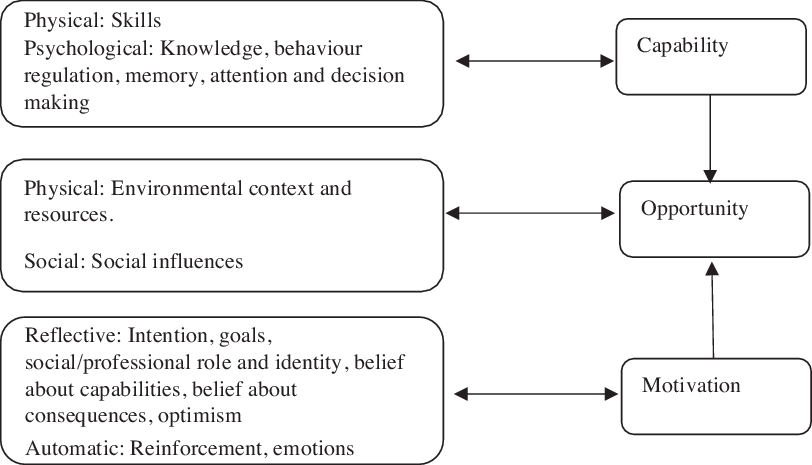

The behaviour change wheel is a framework for designing and evaluating interventions. At the behaviour change wheel core, there is a model of behaviour known as COM-B model, which stands for Capability (C), Opportunity (O), Motivation (M) and Behaviour (B) and posits that all three components influence behaviour, which accounts for all the factors outside the person that make the behaviour possible. The model also posits that both Capability and Opportunity influence Motivation making it the central mediator of the model; therefore, Capability and Opportunity affect behaviour both directly and indirectly. According to the COM-B model, in order to change behaviour, one or more of the COM-B components need to change, relating to either the behaviour or behaviours that support or compete with it(Reference Michie, Atkins and West21). In this study, the COM-B model is used to explore perceived barriers and facilitators to identify potential levers for change for adoption of the MIND diet to occur. A ‘behavioural analysis’ of the determinants of MIND diet behaviour will help define what needs to change in order for adoption of MIND diet to occur. This will be a new behaviour to many, as this diet is very new and has not been investigated in this way before. The COM-B model can be further elaborated by the Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF)(Reference Cane, O’Conner and Michie22) (see Fig. 1). Although the TDF is descriptive and fails to postulate the link between domains(Reference Francis, Eccles and Johnston Bonetti23), it consists of fourteen domains covering the spectrum of behavioural determinants and can be mapped directly onto the COM-B components(Reference Cane, O’Conner and Michie22), which specifies the relationship between domains in regard to a person’s capability, motivation and opportunity to enact a behaviour Reference Michie, Atkins and West21 and includes constructs aligned with other behaviour change theories such as the theory of planned behaviour(Reference Ajzen24). Each domain of the TDF is further elaborated by a number of core components such as belief about capabilities which include self-efficacy, control of behaviour and confidence(Reference Cane, O’Conner and Michie22). The comprehensive coverage of the TDF allows researchers to analyse the most important domains specific to their target behaviour, allowing a crucial step in predicting and ultimately changing dietary behaviour. By providing a wider range of behavioural determinants, researchers gain a deeper understanding of factors influencing behaviour which can be addressed fully in intervention design.

Fig. 1 Theoretical domains framework domains and corresponding mapping onto the COM-B (capability, opportunity, motivation and behaviour) component

Several qualitative studies have used the COM-B model and TDF to explore barriers and facilitators to dietary behaviour change(Reference Alexander, Brijnath and Mazza25–Reference Bentley, Mitchell and Sutton27). These studies found that the COM-B model and TDF provided a comprehensive framework for describing barriers and facilitators to reducing sugar intake in young adults(Reference Alexander, Brijnath and Mazza25), delivery of a healthy kids check to pre-schoolers(Reference Rawahi, Asimakopoulou and Newton26) and to athlete nutritional adherence from the sports nutritionist perspective in 26–52-year-olds(Reference Bentley, Mitchell and Sutton27). These studies found the COM-B and TDF useful to inform an intervention to promote behaviour. Furthermore, studies have designed dietary interventions based on the COM-B model to promote the Mediterranean diet in adults at risk of CVD(Reference McEvoy, Moore and Cupples28), an app to improve eating habits of adolescents and young adults(Reference Rohde, Duensing and Dawczynski29) and a text messaging service targeting healthy eating for children in a family intervention(Reference Chai, May and Collins30).

This study investigates the perceived barriers and facilitators to adopting the MIND diet in midlife (40–55 years). As we are looking to promote healthy ageing, we are investigating modifiable risk factors in the prevention of cognitive decline. Research has found that a good quality diet at midlife seems to be strongly linked to better health and well-being in older life(Reference Samieri, Sun and Townsend31). Previous research found that adherence to a healthy dietary pattern in midlife was positively associated with cognitive functioning(Reference Kesse-Guyot, Andreeva and Jeandel32).

There is currently no study investigating adoption of the MIND diet in midlife. This study addresses this gap in the literature and highlights the perceived barriers and facilitators to adopting a diet that may promote brain health at midlife and will be used to inform an intervention design.

The aim of this study was to explore perceived capability, opportunity and motivation to adopting the MIND diet among middle-aged (40–55 years) adults. The resulting information will be used to inform the design of an intervention to promote the MIND diet in middle-aged adults in the UK.

Methods

Design

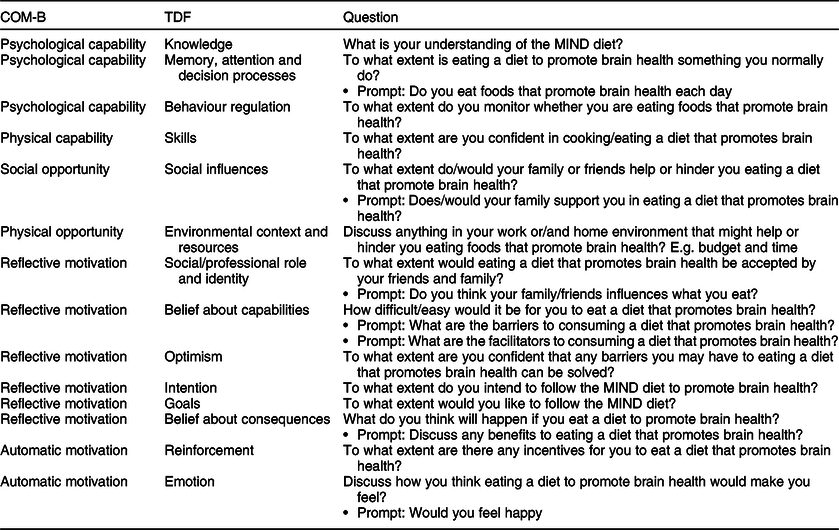

A mixed methods qualitative design was used to elicit beliefs surrounding Capability, Opportunity, Motivation and Behaviour (COM-B) with adopting the ‘MIND’ diet. Capability, motivation and opportunity were further elaborated into fourteen domains, using a more detailed tool to understand behaviour, the TDF. Interviews and focus groups generate different information from participants. Research shows that while focus groups generate a wider range of ideas and views than that of interviews(Reference Krueger33), one-to-one interviews capture more detail than focus groups and offer more insight into participants personal thoughts and experiences(Reference Kidd and Parshall34). In accordance with the COM-B framework, collecting information to understand the target behaviour, data should be collected from different sources as the most accurate picture will be informed by multiple perspectives; therefore, both focus groups and interviews were conducted(Reference Michie, Atkins and West21) and lasting between 30 and 60 min each (see Table 1). The interview and focus group questions were based on guidance using the COM-B(Reference Michie, Atkins and West21) model and TDF(Reference Cane, O’Conner and Michie22) (Table 1). The model and framework were used both in developing the interview schedule and informing the content analyses used. A topic guide was developed using the TDF(Reference Cane, O’Conner and Michie22). The TDF consists of a comprehensive set of fourteen domains into which all determinants of adherence to implementation of a behaviour can be organised (see Table 1). The TDF can be mapped onto the overarching COM-B model(Reference Michie, Atkins and West21), which posits that three key components are necessary for any behaviour—capability, opportunity and motivation.

Table 1 Interview/focus group questions asked to participants in accordance with the theoretical domains framework (TDF) and COM-B model

COM-B: Capability (C): Psychological or physical ability to enact behaviour; Opportunity (O): Physical and social environment that enables behaviour. Motivation (M): Reflective or automatic mechanisms that activate or inhibit behaviour; Behaviour (B); MIND, Mediterranean-DASH Intervention for Neurodegenerative delay; DASH, Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension.

Participants

According to similar behaviour change theories, the ideal sample size for elicitation studies is twenty-five(Reference Francis, Eccles and Johnston Bonetti23). Also, similar to other qualitative studies using the COM-B and TDF(Reference Alexander, Brijnath and Mazza25,Reference Rawahi, Asimakopoulou and Newton26) , twenty-five participants were recruited onto the study, to take part in either a focus group or an interview. Participants were selected for interview or focus group based on their convenience to attend, which took place either in their local community hall, library, workplace or home. Participants were both Caucasian men and women aged between 40 and 55 years. Participants were recruited via email, Facebook and face to face, which took place in a supermarket. Interested participants were emailed a participant information sheet, consent form and a ‘MIND DIET’ booklet, explaining the elements of the MIND diet. Participants approached face to face were given the booklet explaining the MIND diet and asked to contact the researcher if interested in taking part, at which time, were emailed the participant information sheet and consent form. All interested participants were asked to contact the researcher by email. Dates, times and venue were arranged for focus groups and interviews.

Inclusion criteria: Male or female aged between 40 and 55-years-old living in Northern Ireland, who have no food allergies or intolerances.

Exclusion criteria: Participants following specific diets that excluded food groups, such as veganism, vegetarian and Atkins, were excluded from the study as these diets exclude foods such as fish, poultry and wholegrains, which are specific to the MIND diet. Participants with food allergies and/or intolerances were also excluded from the study.

Procedure and materials

Participants were contacted by email, Facebook and face to face. All participants were asked to complete a personal information form which further asked if they followed a specific diet and sign the consent form before the interview/focus group began. Before interview/focus group began, there was an in-depth discussion on the MIND diet and its components between participant and researcher to ensure participants understood what the diet entailed. Participants were informed of what foods to eat, how often to eat foods and portion sizes required. There was also discussion on dementia risk factors and prevalence in the UK. The questions tapped into the components of the COM-B and TDF, that of Capability, Opportunity, Motivation and Behaviour towards consuming a healthy diet. Interviews/focus groups were approached the same in terms of discussion and questions asked and were audio recorded using a hand-held recorder.

Participants were informed that the study was voluntary and that they were free to withdraw at any time. They were assured of confidentiality regarding any personal information they supplied to the researcher.

Data analyses

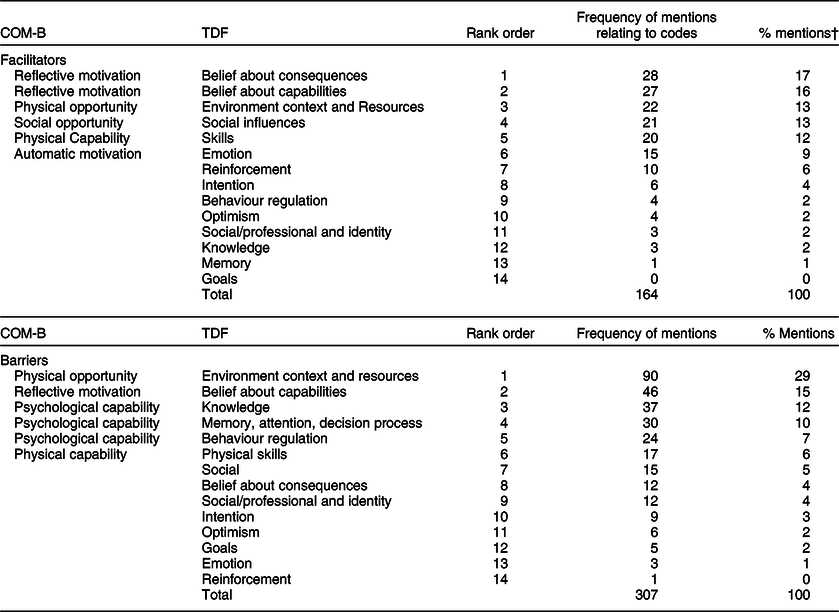

The data was transcribed verbatim and analysed using thematic analyses(Reference Braun and Clarke35). Both researchers have extensive experience and training in thematic/content analysis employed within theory of behaviour change frameworks and to inform intervention design. Researchers attended specific workshops on the COM-B framework. L.S. is a Health Psychologist and D.T. a trainee Health Psychologist, with an array of skills and experience in qualitative research analysis and the use of behaviour change theories. Two researchers independently read through the entire data set and coded the data from each transcript and assigned initial ‘code names’. Researchers kept a reflective diary to ensure a clear overview of the material. Each code was noted as either ‘barrier’ or ‘facilitator’, depending on the context in which the code occurred. There was an initial 95 % agreement of codes, which demonstrates an acceptable level of agreement(Reference Hartmann36). Discussion between researchers resolved any differences within the coding process. After agreement on codes had been made, an additional step in analysis was taken by applying summative content analysis(Reference Hsieh and Shannon37), which involved both researchers searching the text for occurrences of codes and frequency counts for each identified code were calculated. Using a common approach(Reference Brussiers, Patey and Francis38,Reference Lake, Browne and Ress39) , TDF domains were judged based on the frequency count of coding for each TDF domain, which had been aggregated from all the factors and behaviour-specific belief statements within that domain. TDF domains were then rank-ordered according to the frequency coding to identify which components and domains of the theoretical models were the main barriers and facilitators to the adoption of the MIND diet (see Table 2).

Table 2 Barriers and facilitators in rank order of mentions in relation to Mediterranean-DASH Intervention for Neurodegenerative delay (MIND) diet in 40–55-year-olds: COM-B and theoretical domains framework (TDF) domains (n 25) *

COM-B: Capability (C): Psychological or physical ability to enact behaviour; Opportunity (O): Physical and social environment that enables behaviour. Motivation (M): Reflective or automatic mechanisms that activate or inhibit behaviour; Behaviour (B); MIND, Mediterranean-DASH Intervention for Neurodegenerative delay; DASH, Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension.

* Information above the thick black line represents the top six reported domains of the TDF and corresponding COM-B components. Eighty percentage of the data fell into the top six TDF domains.

† Mentions: Spoken word/words in relation to codes/themes/subthemes emerging from questions asked regarding MIND diet.

Results

A total of twenty-five participants took part in the study. A total of fifteen individual interviews and two focus groups were conducted to gather the data for this study. One focus group included six participants, and the second focus group included four participants. Participants were both male (40 %) and female (60 %) aged between 40- and 55-years-old with an average age of 45 years. Forty percentage of participants were of low socio-economic status. Forty-four percentage of participants had children living at home, and fifty-six percentage of participants lived rurally compared with forty-four percentage living in an urban area (see Table 3 for participants’ characteristics).

Table 3 Summary characteristics of interview/focus group participants (N 25)

* Education: level of education obtained within a discipline or profession. Higher education = undergraduate/postgraduate degree: Further education = any study after secondary school that does not include higher education, such as higher national diploma, higher national certificate, apprentices for industry such as hairdressing, plumbing.

Theoretical framework

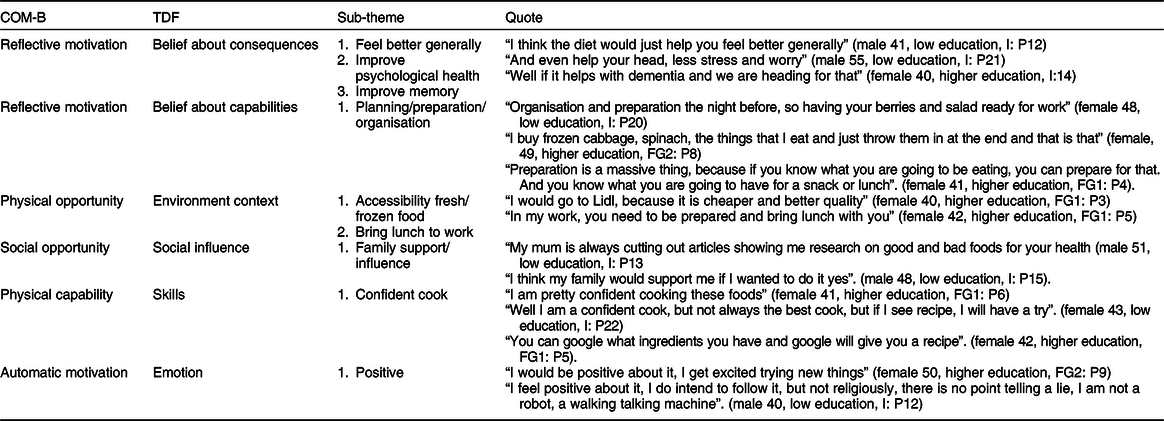

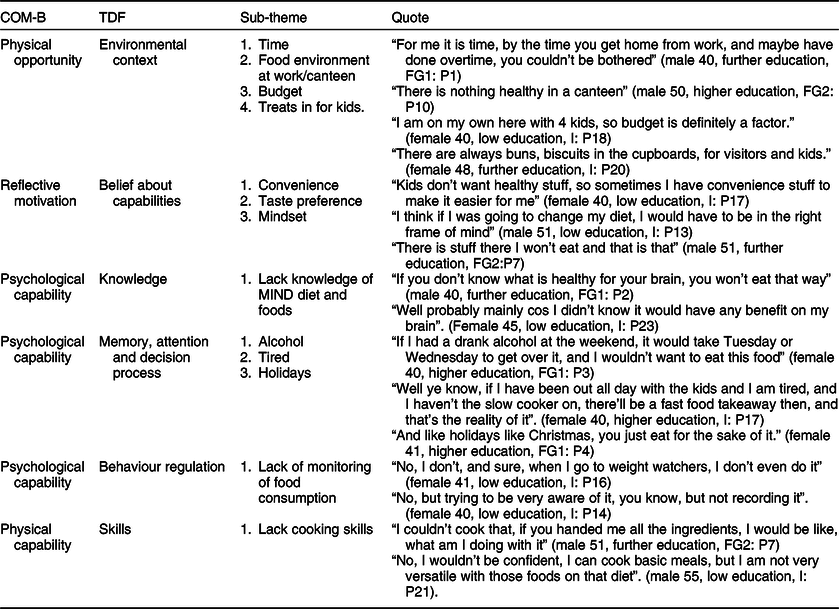

The transcripts provided data from all the fourteen domains of the TDF and all the components of the COM-B model. All the perceived facilitators and barriers could be fitted into one of the TDF domains and mapped onto the COM-B model, with 65 % of all mentions reported as barriers to adopting the MIND diet, compared with 35 % of mentions reported as facilitators. The most commonly reported domains were belief about consequences, belief about capabilities and environmental context/resources, and the least commonly reported domains were goals and optimism (see Tables 4 and 5 for quotes).

Table 4 Key facilitators, themes and quotes (n 25)

COM-B, Capability, Opportunity, Motivation, Behaviour; TDF, Theoretical Domains Framework; FG1, focus group 1; FG2, focus group 2; I, interview; P, participant.

Table 5 Key barriers, themes and quotes (n 25)

COM-B, Capability, Opportunity, Motivation, Behaviour; TDF, Theoretical Domains Framework; FG1, focus group 1; FG2, focus group 2; I, interview; P, participant.

Capability

According to the COM-B model, for behaviour to occur, there must be the capability to do it. Capability can be either psychological (knowledge, psychological skills or stamina) to perform the behaviour or ‘physical’ (having the physical skills, strength or stamina) to perform the behaviour.

Psychological capability

Psychological capability was a COM-B component identified as a barrier to participants’ adoption of the MIND diet. Twenty-nine percentage of barriers to adopting the MIND diet fell into the psychological capability component of the COM-B model. These barriers also fell into three of the fourteen TDF domains, knowledge, memory, attention and decision processes, and behavioural regulation.

Knowledge

All participants reported that they had never heard of the MIND diet prior to the current study.

Most participants reported that they did not know that certain foods were associated with brain health.

Memory, attention and decision processes

The current study defined memory, attention and decision processes as the role of memory and attention to ensure adoption of the MIND diet, and ‘life distractions’, such as alcohol and tiredness, which may limit attention control with respect to eating foods that promote brain health. Several of the participants reported that alcohol is a barrier to eating brain healthy foods.

Another ‘distraction’ reported by participants was being tired. This was mainly due to participants being at work all day or having a long day with the children and too tired to cook when they came home. One participant reported eating sugary foods because of tiredness, to keep him going throughout the day.

Behaviour regulation

In terms of dietary patterns, behaviour regulations are the steps taken to ensure that food intake is remembered and conducted and steps taken to break unhealthy habits. In this study, most of the participants did not monitor their food intake. However, most of the participants viewed monitoring of food, with weight management programmes.

However, several participants stated that while they did not record their food intake, they were aware of what they ate.

Physical capability: skills

Physical skills are defined as the level of self-efficacy in cooking/eating with MIND diet foods. Six percentage of the barriers to adoption of the MIND diet fell into the TDF skills domain and mapped onto the physical capability component of the COM-B model.

Cooking skills were reported to be a barrier to adoption of the MIND diet. Those participants who reported cooking skills as a barrier tend to be married men. However, most of the participants who reported lack of cooking skills were particular to a food in the MIND diet that they usually did not eat.

Skills were also reported to be a facilitator in this study, with 12 % of all facilitators falling into the TDF skills domain. Most participants felt confident with cooking with the MIND diet foods.

Also, many participants reported that if they did not know how to cook something, they were confident that they could follow a recipe.

Opportunity

The COM-B model states that for behaviour to occur, there must be the opportunity for the behaviour to occur in terms of a conducive physical and social environment.

Physical opportunity

Barriers relating to physical opportunity was the most commonly reported barrier in this study, with 29 % of all barriers falling into this component. Physical opportunity is defined in terms of what the environment facilitates in terms of time, resources, location, physical barriers etc. The TDF domain related to this component is environmental context and resources.

Environmental context and resources

This domain is defined as any circumstance of a person’s situation or environment that discourages or encourages the development of skills and abilities, independence, social competence and adaptive behaviour, environmental stressors, resources, salient events and person × environmental interaction. For example, cost of foods, lack of time, does not do the shopping or cooking, accessibility of cheap fresh foods.

Several participants reported that their work environment was a barrier to eating MIND diet foods. In particular, their facilities to cook at work and the canteen at work.

Time was another major barrier for most participants, especially those who were in employment. Participants reported that having worked all day, they did not have the time to cook fresh food all the time. Also, those participants who have children reported time to be a barrier. Participants reported that getting children ready for school or after school, homework and activities, took the time away from cooking healthy meals.

Having treats in the house and in the workplace is reported to be a major barrier in eating MIND diet foods. All participants with children reported having treats in for the kids but would eat the treats themselves. Also, all those participants who were employed reported that treats at work was a barrier to eating MIND diet foods. Budget was reported to be a barrier to buying some of the MIND diet foods, such as berries and nuts, as these foods are reported as expensive. This was the view of those participants who were either not working or in low paid jobs.

Environmental context and resources domain were also reported as being a facilitator to adoption of the MIND diet. Participants reported that having access to cheap fresh/frozen foods would be a facilitator. Some participants reported that, with stores like Lidl and markets where there are cheaper foods, there is really no ‘excuse’ to not eat healthy.

Participants also reported that a lot of food can be bought frozen, such as fruit, vegetables, chicken and fish and that it is cheaper and a good way of preparing meals for the week ahead. Participants also reported that a facilitator to adopt the MIND diet under this domain was to bring lunch to work. Participants felt that, in order to consume the MIND diet foods at work, they would need to bring lunch with them, to avoid eating out or from a canteen.

Social opportunity

Social opportunity was reported as a key facilitator in this study, with 13 % of all facilitators falling into this component. The TDF domain related to this component is social influence.

Social influence

Participants reported family support/influence as a key facilitator to adoption of the MIND diet. Participants reported that they felt that family would support them if they were to adopt the diet. Participants also reported that family influence would facilitate them in consuming the MIND diet.

Motivation

Motivation is a component of the COM-B model, and there must be strong motivation for the behaviour to occur. Motivation can be divided into ‘reflective’ or ‘automated’.

Reflective motivation

Reflective motivation involved self-conscious planning and evaluations. (Beliefs about what is good or bad). Participants reported reflective motivation to be a barrier to the adoption of the MIND diet, and 15 % of barriers fell into this component of the COM-B model.

Belief about capabilities

Acceptance of the truth/reality about or validity of an ability, talent or facility that a person can put to constructive use: self-confidence, perceived competence, perceived behavioural control, and self-efficacy. The extent to which the individual believes they are able to adopt the MIND diet.

Participants reported that convenience was a barrier to adoption of the MIND diet. Those participants with children reported that their children did not like healthy food or would not eat the MIND diet foods, and rather than making two meals, they ate what the children wanted out of convenience.

Taste preference was also a key barrier to the adoption of the diet under this domain. Some participants reported not liking some of the MIND diet foods, such as leafy greens, nuts or fish. Others were not willing to try different foods or try a different way of cooking those foods. Mindset was another key barrier reported to adoption of the diet within this domain. Participants reported that to change their diet and consume the MIND diet, they would have to be in the right frame of mind. They would need to want to change their diet for a reason and be determined to do so.

There were more facilitators than barriers that fell into the motivation component of the COM-B model. Forty-two percentage of the facilitators in this study fell into the motivation component of the COM-B model. Seventeen percentage of facilitators fell into the TDF belief about consequences, 16 % of facilitators fell into belief about capabilities and 9 % of facilitators fell into TDF emotion.

Belief about consequences

This domain is defined as the anticipated outcomes of not eating brain healthy foods, anticipated or experienced outcomes of eating brain healthy foods (positive or negative).

Participants reported that if they were to consume the MIND diet, they felt that this would make them feel better generally and improve memory. Some participants also reported that with the better quality of food in the MIND diet and the reduction of fat and sugar, they felt, their psychological health would improve.

Belief about capabilities

It was reported that in order to facilitate participants adopting the MIND diet, they would need to be prepared, organised and planned. Participants reported leading busy lives, with work and children and while time and convenience were a barrier to consuming the diet, if they were to have the MIND diet foods in the house, organise and prepare meals in advance or at least have an idea of what to cook, this would help facilitate adoption of the MIND diet.

Automatic motivation

Automatic motivation was reported as a facilitator to adoption of the MIND diet, with 9 % of facilitators falling into the TDF emotion domain.

Automatic motivation involves wants and needs, desires, impulse and reflex responses.

Emotion

Most participants reported feeling positive when asked how they feel about the prospect of adopting the MIND diet. However, this did not necessarily coincide with their intention to do so.

Discussion

This study sought to elicit factors influencing adoption of the MIND diet in midlife in the UK. This is the first theory-based qualitative study to explore participants’ barriers and facilitators to adopting the MIND diet. Results found that 80 % of barriers and facilitators fell into six of the TDF domains, with the main barriers reported as environmental context and resources, belief about capabilities, knowledge, memory, attention and decision-making, behaviour regulation and physical skills, and the main facilitators reported as belief about consequences, belief about capabilities, environmental context and resources, social influences, skills and emotion. Results confirmed earlier findings regarding common barriers and facilitators to adopting or adherence to dietary change, including budget(Reference Petroka, Dychtwald and Milliron40), time and taste preference(Reference De Mestral, Stringhini and Marques-Vidal41), and convenience and cooking skills(Reference Hibbs-Shipp, Milholland and Bellowa42).

Participants reported having no knowledge of the MIND diet prior to the study and lacked knowledge in brain healthy foods. Lacking cooking skills was also reported as a barrier, highlighting that ‘capability’ was a key barrier to adopting the MIND diet. Previous research found that a major barrier to meeting dietary recommendations was lack of knowledge regarding dietary recommendations and health benefits(Reference Nickles, Lopez and Liu43) and lack of information on healthy foods(Reference Ashton, Hutchesson and Rollo44). Previous research found that not knowing what to eat or how to eat or cook healthily was a barrier to healthy eating(Reference Baruth, Sharpe and Wilcox45). Many participants reported not eating beans and lentils, which are part of the MIND diet. This was mainly due to lack of knowledge on how to prepare beans and how to make them tasty. This finding is similar to previous research that found lack of knowledge on how to prepare pulses, a barrier to their consumption(Reference Desrochers and Brauer46,Reference Phillips, Zello and Chilibeck47) . Beans may not be a common staple in the Northern Irish population and, therefore, may explain why families report similar barriers regardless of income or where they live.

Participants reported a lack of monitoring their food intake which also highlights ‘capability’ as a key barrier to adoption of the MIND diet. Research found that behaviour regulation was associated with changes in dietary outcomes(Reference Greaves, Sheppard and Abraham48) and that self-monitoring specifically showed a positive change in diet(Reference Maas, Hietbrink and Rinck49). Maas et al. found that self-monitoring reduced snack eating but not alcohol consumption. However, this finding is in line with other research that suggests self-monitoring of alcohol consumptions to be weak(Reference Korotitsch and Nelson-Gray50) or absent(Reference Hufford, Shields and Shiffman51,Reference Simpson, Kivlahan and Bush52) .

Opportunity was highlighted as a barrier and facilitator to the adoption of the MIND diet, with physical opportunity reported as the main barrier. A major theme to emerge was environmental context and resources, with ‘budget’ being a significant factor, mainly due to the expense of the healthy components of the MIND diet, such as fruit, nuts and fish. Budget was only reported as a barrier by those participants who were of low socio-economic status. These findings are in line with previous research that found food cost to play an important role in determining people’s food choice and consumption(Reference Kearney, Kearney and Gibney17) and that it is the healthy component of a whole dietary pattern, such as fruit and nuts of the Mediterranean diet, that is associated with higher cost(Reference Tong, Imamura and Monsivais53). This finding is supported in the literature in a recent meta-analysis(Reference Conklin, Monsivais and Wareham18) that found healthy foods such as fruit, vegetables and nuts to be more expensive than processed foods, refined grains and meat. Therefore, this suggests that budget could be a main barrier to adopting a healthy dietary pattern amongst those of low socio-economic status.

However, previous research compared the actual cost for a four-member family with the cost of the same family following a Mediterranean diet and found that the monthly expenditure was slightly higher on the Mediterranean diet in the overall budget(Reference Germani, Vitiello and Giusti54). However, after increasing the budget for fruit and vegetables, and reduced budget for processed meat and sweets, the overall budget for both diets was similar and therefore it was concluded that lower adherence to the Mediterranean diet was not related to budget, but rather, a substantial difference in allocating budget to the different food groups, for example, less money on fruit and vegetables. Similar findings were found in other research(Reference Kretowicz, Hundley and Tsofliou20,Reference Bernstein, Bloom and Rosner55,Reference Goulet, Lamarche and Lemieux56) .

Physical opportunity was also reported to be a facilitator in this study, with environmental context and resources also emerging as a theme. Access to fresh cheap produce was reported as a barrier and facilitator in the current study. The results found that those living in rural areas to be a barrier more than those living in a city, where there may be more access to markets and bigger stores within reach. Research found that stores with more nutritious food are a longer distance away from rural areas(Reference Maley, Warren and Devine57,Reference Neill, Leipert and Garcia58) . However, those who could grow their own food or had access to farmers’ markets were a facilitator to healthy eating(Reference Seguin, Connor and Nelson59). Participants who received nutrition education and access to a garden to eat fruit and vegetables reported to eat the recommended daily fruit and vegetables(Reference Barnidge, Baker and Schootman60).

Social influence was reported as a key facilitator in this study with social influence emerging as a theme. Participants reported that family support and influence were a factor that would help them adopt the MIND diet. This finding is consistent with the previous research that found family influence as a facilitator in nutritional knowledge and healthy habit(Reference Doldren and Webb61). Other research found that those who perceived family support were more likely to eat more fruit and vegetables, wholegrains and consume less meat and fats(Reference Pawlak and Colby62,Reference Walker, Pullen and Hertzog63) . However, family has been found to be a barrier to healthy eating(Reference Baruth, Sharpe and Wilcox45). It was reported that women were pressurised to eat more and that they were not supported if they were trying to eat a healthy diet(Reference Baruth, Sharpe and Wilcox45). However, the sample in this study was with African American women, and they may feel pressure to eat more, as food and the context of eating their traditional food is important to their cultural identity. The women in this study reported that larger curvaceous bodies are the ideal body type for African American women and that food was a big part of their customs(Reference Baruth, Sharpe and Wilcox45).

Motivation was also highlighted as a barrier and facilitator to the adoption of the MIND diet. Belief about capabilities was a major theme to emerge as a barrier. Participants reported convenience to be a factor associated with their ability to adopt the MIND diet. Previous research also found convenience to be a barrier to healthy food choices(Reference De Mestral, Stringhini and Marques-Vidal41) and that fast food and unhealthy snacks were more convenient(Reference Seguin, Connor and Nelson59).

The results from this investigation have created a ‘behavioural diagnosis’ of what needs to change from the COM-B analysis in order for dietary behaviour change to occur. The COM-B model and TDF are used as a starting point to understand behaviour in the context in which it occurs. This behavioural diagnosis has identified that all three components of the COM-B model can be targeted as potential levers of change. Linking the COM-B model to the BCW allows for a systematic approach in subsequent intervention development and evaluation(Reference Michie, Atkins and West21). While there has been a wide range of behavioural models developed, such as the theory of planned behaviour(Reference Ajzen24), they only help to understand or predict behaviour(Reference Kok, Schaalma and Ruiter64) and do not help to understand behaviour change(Reference Brug, Oenema and Ferreira65) or design interventions. The behaviour change wheel guides this transition and, in designing the intervention, the COM-B components to be targeted will be mapped onto intervention functions and policy categories suggested by Michie et al.(Reference Michie, Atkins and West21) that are expected to be effective in bringing about change, such as education, persuasion and coercion. Following the identification of intervention function and policy categories, the content of the intervention will be identified in terms of which behaviour change techniques and mode of delivery are best to promote behaviour change.

Limitations

This study was undertaken in a small sample of men and women, although in line with other COM-B studies(Reference Avery and Patterson66) and dietary studies(Reference Kretowicz, Hundley and Tsofliou67). Furthermore, while we were able to include participants with different sociodemographic backgrounds, this study was conducted only with a white Irish sample. However, 98 % of the population in Northern Ireland are white, with 88 % born in Northern Ireland(68); therefore, the current studies’ sample reflects the majority of the Northern Ireland population. Further research to collect data from a more ethnically diverse population is needed. Moreover, our findings may be context based and, therefore, not generalisable to the whole population. However, our study did not aim to find generalisability, rather to find a deeper understanding of the people’s attitudes in midlife towards the adoption of the MIND diet that might need addressing in future interventions. Researcher subjectivity may be a limitation to our study; however, codes and themes were identified by a second researcher which suggest that the themes drawn have credence beyond interpretation of the lead researcher. Focus groups run the risk of introducing bias(Reference Harrison, Milner-Gulland and Baker69), resulting from an individual’s desire to conform to social acceptability(Reference Acocella70). However, in this study, focus group participants were acquaintances and, therefore, may reduce the risk of social acceptability. Barriers and facilitators reported in this study are ‘perceived’ and, therefore, may have limited value in predicting uptake of the MIND diet. While there was a discussion on prevalence rates of dementia in the UK with participants, their perceived risk of dementia was not addressed in this study. Nevertheless, participants felt their knowledge of dementia increased, as had their knowledge of brain healthy foods. Further research should address perceived risk of dementia and its association with intention to eat a brain healthy diet.

Strengths

The COM-B model is an established method for understanding behaviour and used extensively in behaviour change interventions, including dietary studies(Reference Chai, May and Collins30,Reference Cha, May and Collins71) . To our knowledge, this study is the first study to explore barriers and facilitators to adopting the MIND diet, and the first study to use the behaviour change wheel to investigate the MIND diet. This was the first study to apply the TDF to explore peoples understanding and perceptions of a whole dietary pattern. Moreover, this study used the COM-B model as an additional step in the thematic analysis, which increased the study’s efficiency and showed that the entire framework was adequate for purpose.

Conclusion

Findings from this study provide insight into the personal, social and environmental factors that participants report as barriers and facilitators to adoption of the MIND diet among middle-aged adults living in the UK. Using the TDF and COM-B model is a starting point for understanding behaviour in specific contexts and is able to make a ‘behavioural diagnosis’ of what needs to change, to modify behaviour. The TDF and COM-B model has allowed us to gain deep understanding and increased awareness of the current situation and has clarified which barriers and facilitators can be targeted to improve adherence to the MIND diet. The results presented above suggest that there is potential to optimise all three components of the COM-B model to increase adherence to the MIND diet, highlighting the importance of addressing these factors when designing behaviour change interventions. Furthermore, understanding barriers and facilitators to the adoption of the MIND diet may help health professionals working with individuals/communities to help prevent or reduce the risk of cognitive decline. The behaviour change wheel will be used to systematically design and develop an intervention to increase adherence to the MIND diet.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: The authors would like to thank all the participants who took part in the study and to the businesses that allowed access to their customers. Financial support: The Department for the Economy (DfE) sponsored the research for this paper, 2017. Conflict of interest: The authors declare they have no conflicts of interest. Authorship: All authors contributed to formulating the research questions and the design of the study. D.T. collected all the data and wrote the article with input from E.E.A.S. and J.M.M. D.T. and E.E.A.S. analysed the data. E.E.A.S. and J.M.M. supervised the project. Ethics of human subject participation:: This study was conducted according to the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki, and all procedures involving study participants were approved by the School of Psychology Staff and Postgraduate Ethics Filter Committee. Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects/patients.