INTRODUCTION

The Abri Casserole is located in the middle part of the limestone cliff overlooking the town of Les Eyzies-de-Tayac (Dordogne, France), near the confluence of the Vézère and Beune Rivers (Figure 1; 44°56'11.221"N, 1°0'51.663"E). Discovered at the beginning of the twentieth century, it was first exploited by Alphonse Chadourne—then a farrier in the town of Les Eyzies—and revealed several Solutrean lithic artifacts that were bought and published in the late 1930s by Harper Kelley (Reference Kelley1939). It was not until the early 1990s that an extensive excavation was carried out by the Association pour les Fouilles Archéologiques Nationales (AFAN) prior to the extension of the Musée National de Préhistoire (MNP). Conducted by Luc Detrain between 1991 and 1993 (Detrain et al. Reference Detrain, Kervazo, Aubry, Bourguignon, Guadelli, Marcon and Teillet1991, Reference Detrain, Aubry, Beyer, Bidart, Bourguignon, Diot, Guadelli, Kervazo, Legrand, Leroyer, Limondin, Marcon, Morala, Platel and Rouzo1992, Reference Detrain, Aubry, Bourguignon, Legrand, Beyer, Bidart, Chauvière, Cleyet-Merle, Diot, Fontugne, Geneste, Guadelli, Kervazo, Lemorini, Leroyer, Limondin, Marcon, Morala, O’Yl and Platel1994), this new excavation covered a 31 m2 area encompassing the previous Chadourne excavation and revealed a sequence of 13 archaeological levels within 8 lithostratigraphic units (Table 1). The sequence records the techno-cultural evolution of hunter-gatherer societies from the Middle Gravettian (archaeological levels NA12 and NA11) up through the Solutrean (NA9-10a–NA7), Badegoulian (NA6–NA4), and possibly the Magdalenian (NA3–NA1?). The exceptional nature of this record rests on the existence of singular, extremely rare and, at the time, poorly known assemblages documenting several blurred “segments” of the southwestern European Upper Paleolithic (UP) sequence: the Gravettian-to-Solutrean transition (NA10b and NA9-10a, attributed to the Final Gravettian and the Protosolutrean, respectively: Aubry et al. Reference Aubry, Kerzavo and Detrain1995; Zilhão et al. Reference Zilhão, Aubry and Almeida1996) and the Solutrean-to-Badegoulian transition (NA6, attributed to the Early Badegoulian: Morala Reference Morala1993). These phases of “cultural” transition, which occurred within a context of pronounced climatic variability (Heinrich Event 2 to GS 2: Rasmussen et al. Reference Rasmussen, Bigler, Blockley, Blunier, Buchardt, Clausen, Cvijanovic, Dahl-Jensen, Johnsen, Fischer, Gkinis, Guillevic, Hoek, Lowe, Pedro, Popp, Seierstad, Steffensen, Svensson, Vallelonga, Vinther, Walker, Wheatley and Winstrup2014), correspond to key moments in the West European UP sequence. They figure importantly in questions concerning the potential influence of climatic and environmental changes on technological economies and/or human dispersals. While the Protosolutrean is now documented from southwestern France to southern portions of the Iberian Peninsula (e.g. Almeida Reference Almeida, Bar-Yosef and Zilhão2006; Renard Reference Renard2011; Alcaraz-Castaño et al. Reference Alcaraz-Castaño, Alcolea González, de Balbín Behrmann, García Valero, Yravedra Sainz de los Terreros and Baena Preysler2013; Zilhão Reference Zilhão2013), several issues remain that need to be better understood: (1) the local techno-economic mechanisms leading to Vale-Comprido point-yielding industries (Zilhão and Aubry Reference Zilhão and Aubry1995), (2) the timing of this emergence and, in turn, (3) the possible correlation between those changes and the influence of rapid climatic variability on human and faunal communities. Similarly, the reasons behind the techno-economic shift observed between the Upper Solutrean and the Badegoulian in France (e.g. Renard and Ducasse Reference Renard and Ducasse2015; Ducasse et al. Reference Ducasse, Renard, Baumann, Castel, Chauvière, Peschaux and Pétillon2019b) remain unclear and various hypotheses have been advanced to explain this transition: anthropological reasons (i.e. migrations; local socio-economic processes) or “taphonomic” phenomenon (i.e. gaps in the archaeological record). Parallel to the examinations and reassessments of these lithic and osseous industries, it is paramount to pursue radiocarbon dating programs focused not only on Upper Solutrean assemblages but also, when possible, those of the still poorly understood Early Badegoulian.

Figure 1 Location of the Casserole rockshelter (Les Eyzies-de-Tayac, Dordogne) and Upper Paleolithic sites mentioned in the text.

Table 1 The Casserole lithostratigraphic and archaeological sequence (according to Detrain et al. Reference Detrain, Kervazo, Aubry, Bourguignon, Guadelli, Marcon and Teillet1991; Detrain Reference Detrain1992a, Reference Detrain1994; Aubry et al. Reference Aubry, Kerzavo and Detrain1995; Aubry and Almeida Reference Aubry and Almeida2013).

An improved understanding of the chronology of occupations at Casserole rockshelter is instrumental in achieving this objective. Several bulk bone samples from the principal Badegoulian levels of Casserole were selected for 14C dating during the course of the excavation (Detrain et al. Reference Detrain, Aubry, Bourguignon, Legrand, Beyer, Bidart, Chauvière, Cleyet-Merle, Diot, Fontugne, Geneste, Guadelli, Kervazo, Lemorini, Leroyer, Limondin, Marcon, Morala, O’Yl and Platel1994). While the ages obtained via the beta counting method were consistent with the ages then available from other key Badegoulian sequences in southwestern France (see below; Ducasse et al. Reference Ducasse, Pétillon and Renard2014: 40), they were not the object of a dedicated publication detailing methods, results, and chronocultural interpretations. Furthermore, since the initial monograph project was not completed, the first dating effort was never extended to the other archaeological units, thus leaving a key part of the archaeological sequence undated (i.e. the Late Gravettian and Early Solutrean levels). Since that time, the results of several dating programs that take advantage of important methodological improvements of the past 25 years (i.e. AMS method, pretreatment process developments, etc.) have served to refine our chronological understanding of the period from the Gravettian to the Magdalenian in southwestern France (Henry-Gambier et al. Reference Henry-Gambier, Nespoulet, Chiotti, Drucker, Lenoble, Nespoulet, Chiotti and Henry-Gambier2013; Ducasse et al. Reference Ducasse, Pétillon and Renard2014; Langlais et al. Reference Langlais, Laroulandie, Costamagno, Pétillon, Mallye, Lacrampe-Cuyaubère, Boudadi-Maligne, Barshay-Szmidt, Masset, Pubert, Rendu and Lenoir2015; Barshay-Szmidt et al. Reference Barshay-Szmidt, Costamagno, Henry-Gambier, Laroulandie, Pétillon, Boudadi-Maligne, Kuntz, Langlais and Mallye2016; Banks et al. Reference Banks, Bertran, Ducasse, Klaric, Lanos, Renard and Mesa2019; Verpoorte et al. Reference Verpoorte, Cosgrove, Wood, Petchey, Lenoble, Chadelle, Smith, Kamermans and Roebroeks2019; Ducasse et al. Reference Ducasse, Renard, Baumann, Castel, Chauvière, Peschaux and Pétillon2019b). The available beta counting ages for the Badegoulian levels now appear to be in conflict with the currently accepted AMS chronology for the end of the Pleniglacial in southwestern Europe. It was thus deemed important to renew and complement the chronology of the Upper Paleolithic sequence of the Abri Casserole.

Building on a synthetic review of Casserole’s 1990s dating program that attempts to restore its lost coherence and highlight its limits, the aim of this paper is twofold: (1) summarize the results of recent AMS dating efforts carried out in the early 2010s but only available in fieldwork reports (Lenoble et al. Reference Lenoble, Morala and Cosgrove2013; Lenoble and Cosgrove Reference Lenoble and Cosgrove2014); and (2) present new AMS ages obtained between 2017 and 2018 for the Badegoulian and Magdalenian levels in the framework of a new monograph project (A. Lenoble and L. Detrain, dir.). Taken together, these two dating campaigns provided 12 new AMS ages. These are discussed at a larger regional scale with respect to specific radiometric methodologies, as well as the timing of the concerned archaeological techno-complexes and some of their associated bone and antler technologies.

THE EXISTING DATA: SUMMARY AND QUESTIONS RAISED

The Badegoulian Levels: A Coherent But Obsolete Chronological Framework

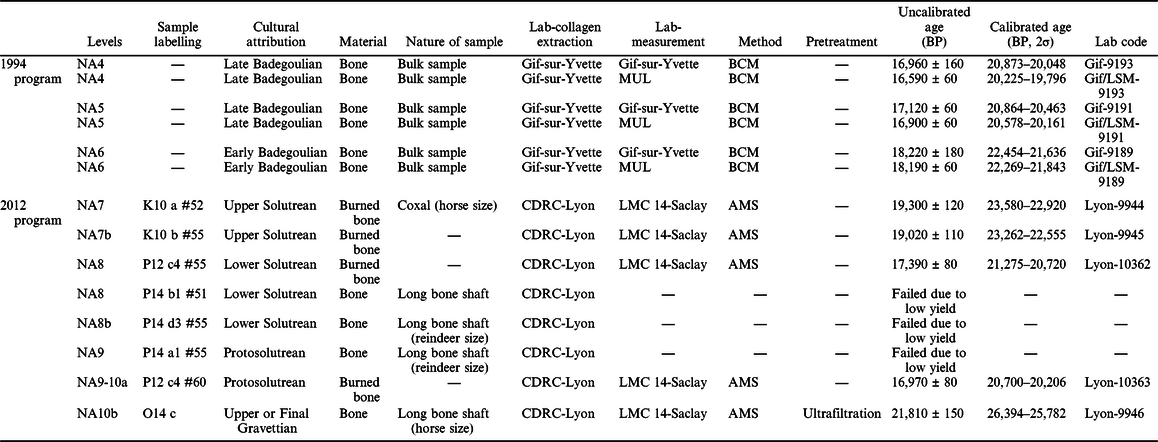

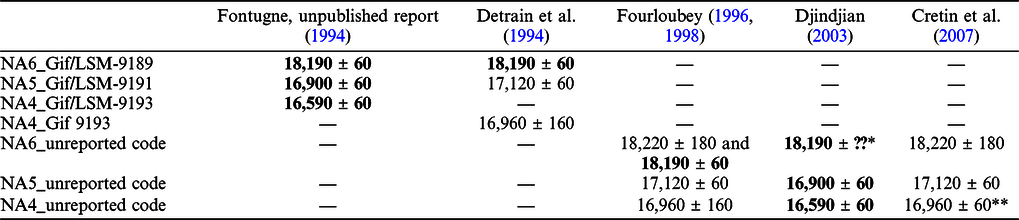

It is important to point out that the characterization and chronological succession of the different “cultural” phases of the Badegoulian is currently based on only a few stratified sites, most of which were excavated without modern methods and/or present “taphonomic” issues (see Ducasse Reference Ducasse2010: 376–382). Among them, Le Cuzoul de Vers rockshelter (Lot, France; Clottes and Giraud Reference Clottes and Giraud1985, Reference Clottes and Giraud1989; Clottes et al. Reference Clottes, Chalard and Giraud2012) figures importantly because (1) it represents the most developed Badegoulian stratigraphy known to-date in southwestern France and documents the very first expressions of the Badegoulian techno-complex (the extremely rare so-called “Early Badegoulian” phase, i.e. layers 27 to 22), to the raclette-yielding Badegoulian (i.e. layers 21 to 1) and (2) it is characterized by a robust chronological framework (Oberlin and Valladas Reference Oberlin, Valladas, Clottes, Giraud and Chalard2012; Ducasse et al. Reference Ducasse, Pétillon and Renard2014). Less than a decade after excavations at Cuzoul de Vers had ended, the discovery of a Solutrean-to-Badegoulian sequence that included the “Early Badegoulian” phase was therefore one of the highlights of the Casserole excavation (Detrain Reference Detrain1992a, Reference Detrain1994). Several studies that made up the initial monograph project immediately focused on the typological and techno-economic evolution of lithic and osseous assemblages from the Upper Solutrean to the Early Badegoulian and to the subsequent raclette-yielding (Late) Badegoulian (Aubry Reference Aubry1992; Bidart Reference Bidart1992; Detrain Reference Detrain1992b; Morala Reference Morala1993; Bracco et al. Reference Bracco, Morala, Cazals, Cretin, Ferullo, Fourloubey, Lenoir and Peresani2003). This collective effort was combined with the establishment of a chronological framework based on several beta counting 14C ages: six radiocarbon measurements were obtained in 1994 by dating three bulk bone samples from NA6 (an Early Badegoulian industry considered similar to Le Cuzoul de Vers layers 27 to 22), NA5 and NA4 (both attributed to the raclette-yielding Badegoulian) (Detrain et al. Reference Detrain, Aubry, Bourguignon, Legrand, Beyer, Bidart, Chauvière, Cleyet-Merle, Diot, Fontugne, Geneste, Guadelli, Kervazo, Lemorini, Leroyer, Limondin, Marcon, Morala, O’Yl and Platel1994; Fontugne Reference Fontugne1994). Each of the three bulk (i.e. mix of diaphysis and long bone fragments) samples was submitted first to the Gif-sur-Yvette laboratory, who performed pretreatment and produced preliminary beta counting ages documenting the 22.5–20 cal ka BP interval (Table 2: Gif-9189, Gif-9191 and Gif-9193). Subsequently, a portion of the carbon gas produced by Gif during pretreatment was submitted to the Modane underground laboratory (LSM) in order to improve the accuracy of the preliminary results since the LSM, located 4800 meters below the Fréjus Peak (Alps), is able to reduce potential cosmic interference (e.g. Fontugne et al. Reference Fontugne, Jaudon and Reyss1994; Piquemal Reference Piquemal2012). Background noise is reduced by 70%, allowing for measurements with smaller standard deviations, as shown in Table 2 (Gif/LSM-9189, Gif/LSM-9191 and Gif/LSM-9193). Compared to the more typical standard deviations of 150–200 years obtained at Gif-sur-Yvette, the Modane standard errors do not exceed 60 years, thus placing the Casserole Badegoulian assemblages in a slightly more precise chronological range, between 22.2–19.8 cal ka BP. Therefore, contrary to the preliminary Gif results for the same samples (see Table 2), the Modane ages for NA5 and NA4 (i.e. raclette-yielding industries; see Table 1) have extremely limited overlap, making them more consistent with the archaeological data and stratigraphic order (20.5–20.1 cal ka BP for NA5 versus 20.2–19.7 cal ka BP for NA4). Irrespective of laboratory, the age of the Early Badegoulian from NA6 documents a clearly distinct, older timespan (22.4–21.6 cal ka BP). Beyond transcription errors and systematic omission of lab codes, second-hand publications of results (Fourloubey Reference Fourloubey1998; Djindjian Reference Djindjian and Ladier2003; Cretin et al. Reference Cretin, Ferullo, Fourloubey, Lenoir and Morala2007) are highly contradictory since they often mix the Modane and Gif ages (see Table 3). The Casserole beta counting ages’ “story” is an exemplary case of the progressive loss of information and inadvertent alterations that can occur over time, and whose chance of occurring is increased by the absence of a published source reference. Considering the methodological approach described above, only the three Modane ages should be taken into consideration since the Gif-sur-Yvette measurements were produced only to provide first indications (Fontugne, personal communication).

Table 2 Summary of the beta counting and AMS 14C ages obtained at Casserole from 1994 to 2012 (according to Detrain et al. Reference Detrain, Aubry, Bourguignon, Legrand, Beyer, Bidart, Chauvière, Cleyet-Merle, Diot, Fontugne, Geneste, Guadelli, Kervazo, Lemorini, Leroyer, Limondin, Marcon, Morala, O’Yl and Platel1994; Fontugne Reference Fontugne1994; Fourloubey Reference Fourloubey1996; Fourloubey Reference Fourloubey1998; Djindjian Reference Djindjian and Ladier2003; Lenoble et al. Reference Lenoble, Morala and Cosgrove2013; Lenoble and Cosgrove Reference Lenoble and Cosgrove2014; MUL: Modane underground laboratory; BCM: Beta counting method). Calibration was carried out with OxCal (v4.3.2: Bronk Ramsey, Reference Bronk Ramsey2017) using the IntCal13 calibration curve (Reimer et al. Reference Reimer, Bard, Bayliss, Beck, Blackwell, Ramsey, Buck, Cheng, Edwards, Friedrich, Grootes, Guilderson, Haflidason, Hajdas, Hatté, Heaton, Hoffmann, Hogg, Hughen, Kaiser, Kromer, Manning, Niu, Reimer, Richards, Scott, Southon, Staff, Turney and Plicht2013).

Table 3 Comparison of the published Badegoulian beta counting ages of Casserole (NA6 to NA4), from the analysis report to the second-hand publications. Correct results are indicated in bold (see text for further details).

* This age’s standard deviation, which is presented in the original site report, was not included in the publication indicated for this column.

** The standard error presented in this column’s publication is incorrect.

In the mid-1990s, results were remarkably coherent with the radiometric framework available for the few key dated Badegoulian sequences, most notably from Laugerie Haute Est (Dordogne; Evin et al. Reference Evin, Marien and Pachiaudi1976), Le Cuzoul de Vers (Lot; Clottes and Giraud Reference Clottes and Giraud1989), Abri Fritsch (Indre; Delibrias and Evin Reference Delibrias and Evin1980) and Grotte de Pégourié (Lot; Séronie-Vivien Reference Séronie-Vivien1995) (Table 4). However, after 25 years of methodological improvements (e.g. Evin and Oberlin Reference Evin and Oberlin2000; Higham et al. Reference Higham, Jacobi and Bronk Ramsey2006; Brock et al. Reference Brock, Higham, Ditchfield and Bronk Ramsey2010) and refinement of sample selection procedures, the Casserole beta counting chronology is inaccurate in light of the results of AMS dating programs conducted over the last 15 years. The Badegoulian timespan has become significantly—and systematically—older, as observed at Le Cuzoul de Vers (Oberlin and Valladas Reference Oberlin, Valladas, Clottes, Giraud and Chalard2012; Ducasse et al. Reference Ducasse, Pétillon and Renard2014), Lassac (Sacchi Reference Sacchi2003; Pétillon and Ducasse Reference Pétillon and Ducasse2012) and La Contrée-Viallet (Lafarge Reference Lafarge2014), and it is now accepted that this techno-complex was present in southwestern France between 23–21 cal ka BP (Banks et al. Reference Banks, Bertran, Ducasse, Klaric, Lanos, Renard and Mesa2019; Ducasse et al. Reference Ducasse, Renard, Baumann, Castel, Chauvière, Peschaux and Pétillon2019b). While this chronology encompass the Early Badegoulian level NA6, it should be noted that the raclette-yielding Badegoulian ages from NA5 and NA4 fall outside this timespan and overlap with the current Lower Magdalenian AMS chronology (21–19 cal ka BP: Langlais et al. Reference Langlais, Laroulandie, Costamagno, Pétillon, Mallye, Lacrampe-Cuyaubère, Boudadi-Maligne, Barshay-Szmidt, Masset, Pubert, Rendu and Lenoir2015; Barshay-Szmidt et al. Reference Barshay-Szmidt, Costamagno, Henry-Gambier, Laroulandie, Pétillon, Boudadi-Maligne, Kuntz, Langlais and Mallye2016; Primault et al. Reference Primault, Brou, Bouché, Catteau, Gaussein, Gioé, Griggo Ch, Le Fillatre and Peschaux2020). The causes of this “aging” are various and combined (e.g. bulk bone samples leading to averaged and younger ages; impact of pretreatment processes; taphonomic issues, etc.) as notably demonstrated for the Grotte de Pégourié (Ducasse et al. Reference Ducasse, Pétillon, Chauvière, Renard, Lacrampe-Cuyaubère and Muth2019a). In the case of Casserole, in addition to the high typo-technological homogeneity of the lithic assemblages (Morala Reference Morala1993), preliminary and ongoing work concerning archaeological stratigraphy (refitting studies) supports the high quality of the record, suggesting that the differences between the Casserole beta counting chronology and the current Badegoulian chronology founded on AMS measurements are methodological in nature, thus affecting their comparability.

Table 4 Beta counting radiometric framework of the main Badegoulian sequences available in the 1990s. Calibration was carried out with OxCal (v4.3.2: Bronk Ramsey Reference Bronk Ramsey2017) using the IntCal13 calibration curve (Reimer et al. Reference Reimer, Bard, Bayliss, Beck, Blackwell, Ramsey, Buck, Cheng, Edwards, Friedrich, Grootes, Guilderson, Haflidason, Hajdas, Hatté, Heaton, Hoffmann, Hogg, Hughen, Kaiser, Kromer, Manning, Niu, Reimer, Richards, Scott, Southon, Staff, Turney and Plicht2013).

Questioning the Chronology of the Gravettian-to-Solutrean Transition

Shortly after 2010, subsequent dating work began in the framework of a broader project focused on paleoenvironments and their influence on past human societies (Lenoble et al. Reference Lenoble, Morala and Cosgrove2013; Lenoble and Cosgrove Reference Lenoble and Cosgrove2014). Setting aside the already-dated Badegoulian levels, this project provided an opportunity to evaluate the chronology of the Solutrean levels at Casserole, with the primary objective being to examine the timing of the Gravettian–Solutrean transition in order to elucidate potential links between these typo-technological changes and Heinrich Event 2 (op. cit.). Via the ARTEMIS program (Billard Reference Billard2008), eight bone and burned bone samples derived from the Upper/Final Gravettian (NA10b), Protosolutrean (NA9-10a), Lower Solutrean (NA8) and Upper Solutrean (NA7) levels were selected and sent to the Lyon (CDRC) and Saclay (LMC 14) laboratories to be dated with the AMS method (Table 2). While three samples had insufficient collagen for dating (1 sample for NA9 and 2 from NA8), the results obtained for NA9-10a (16,970 ± 80 BP: 20.7–20.2 cal ka BP) and NA8 (17,390 ± 80 BP: 21.3–20.7 cal ka BP), attributed to the Protosolutrean and the Lower Solutrean respectively, fall surprisingly within the Lower Magdalenian timeframe (see above) and are not stratigraphically coherent. Since no evidence of chronocultural admixture with the uppermost layers has been documented, the hypothesis that these inconsistencies are due to the nature of the dated samples and their pretreatments, which are all composed of burned bone fragments that could not be subjected to ultrafiltration, must be considered.

The phenomenon of a burned bone sample providing an underestimate of the true age of the sample is well-known (see Zazzo Reference Zazzo, Balasse, Brugal, Dauphin, Geigl, Oberlin and Reiche2015) regardless of the period under investigation (e.g. Olson and Broecker Reference Olson and Broecker1961; Berger et al. Reference Berger, Horney and Libby1964). In the specific case of samples from NA9-10a and NA8, technical difficulties were encountered during the acid-base-acid (ABA) pretreatment process: since each sample was turned into powder during the acid washing phase, the small amount of remaining material was subjected to a less intensive basic treatment phase. This reduced the likelihood that recent humic matter was completely eliminated (Oberlin, personal communication), thereby resulting in ages that are underestimates. While the pretreatment (i.e. less-intensive basic treatment) of the Upper Solutrean NA7 burned bone sample theoretically raises the same issues of reliability, a larger amount of material remained. This produced a result (19,300 ± 120 BP: 23.5–22.9 cal ka BP) that correspond well to the age obtained for the burned bone sample from NA7b (19,020 ± 110 BP: 23.2–22.5 cal ka BP), for which the complete pretreatment process was employed. Both results are consistent with reliable regional and extra-regional Upper Solutrean data (Banks et al. Reference Banks, Bertran, Ducasse, Klaric, Lanos, Renard and Mesa2019).

Finally, although these dating efforts failed to directly address the much-debated issue of the Protosolutrean’s precise chronological position (e.g. Aubry et al. Reference Aubry, Kerzavo and Detrain1995; Zilhão and Aubry Reference Zilhão and Aubry1995; Almeida Reference Almeida, Bar-Yosef and Zilhão2006; Renard Reference Renard2011; Alcaraz-Castaño et al. Reference Alcaraz-Castaño, Alcolea González, de Balbín Behrmann, García Valero, Yravedra Sainz de los Terreros and Baena Preysler2013; Calvo and Prieto Reference Calvo and Prieto2013; Haws et al. Reference Haws, Benedetti, Cascalheira, Bicho, Carvalho, Zinsious, Ellis, Friedl, Schmidt and Cascalheira2019; Verpoorte et al. Reference Verpoorte, Cosgrove, Wood, Petchey, Lenoble, Chadelle, Smith, Kamermans and Roebroeks2019), the 14C age obtained for the uppermost Gravettian level NA10b, for which an attribution to the final stage of this techno-complex has been suggested based on the presence of bi-truncated backed bladelets, provides an accurate terminus post quem of around 26 cal ka BP for the Protosolutrean (21,810 ± 50 BP: 26.4–25.8 cal ka BP; Lenoble et al. Reference Lenoble, Morala and Cosgrove2013; Lenoble and Cosgrove Reference Lenoble and Cosgrove2014).

Designing a New AMS Dating Program: Main Objectives

While the second dating program, linked to extra-regional research questions (see above), did not met all expectations due to preservation issues, it did serve to spur renewed interest in Casserole’s archaeological sequence and prompted a new monograph project (A. Lenoble and L. Detrain dir.) that involved a third AMS dating program. This program also benefited from the scientific and financial support of the IMPACT project (W. Banks dir.) that concerned, in part, the same chronological issues (Banks et al., Reference Banks, Bertran, Ducasse, Klaric, Lanos, Renard and Mesa2019). Thus, based on the information presented above, along with additional research on the post-Solutrean assemblages, which included inter-layer refitting analyses, this new dating effort had three principal objectives:

-

Reassess the radiometric framework of the Badegoulian portion of the sequence (NA6–NA4) in order to evaluate the influence of: (1) the dating method employed (i.e. AMS versus beta-counting); (2) the nature of the dated samples (i.e. bulk samples versus individual artifacts); and (3) the pretreatment process (i.e. ultrafiltration) on the final results. With respect to these points, previous work on other Badegoulian sequences (e.g. Pétillon and Ducasse Reference Pétillon and Ducasse2012; Ducasse et al. Reference Ducasse, Pétillon and Renard2014) leads one to anticipate that results should be older by ca. 1000 years;

-

Obtain ages for the uppermost levels (NA3–NA1) in order to evaluate the coherence of previous typo-technological results that place it within a Magdalenian cultural context, and to do so in parallel with a new diagnosis of its associated lithic and osseous assemblages;

-

Attempt to obtain more consistent ages for the lower portion of the Solutrean sequence, especially the Protosolutrean level (NA9-10a). Considering that bones discovered in the eastern and main portions of the excavated area appeared to be non-reliable for radiocarbon dating (Lenoble and Cosgrove Reference Lenoble and Cosgrove2014), plans were made to select material from the western area despite its reduced stratigraphic resolution.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Following methodological approaches previously developed in the frameworks of recent research programs (the Magdatis project: Langlais et al. Reference Langlais, Laroulandie, Costamagno, Pétillon, Mallye, Lacrampe-Cuyaubère, Boudadi-Maligne, Barshay-Szmidt, Masset, Pubert, Rendu and Lenoir2015; Barshay-Szmidt et al. Reference Barshay-Szmidt, Costamagno, Henry-Gambier, Laroulandie, Pétillon, Boudadi-Maligne, Kuntz, Langlais and Mallye2016; the Madapca project: Bourdier et al. Reference Bourdier, Pétillon, Chehmana, Valladas and Paillet2014 and the SaM project: Ducasse et al. Reference Ducasse, Pétillon and Renard2014, Reference Ducasse, Chauvière, Castel, Langlais, Aurière, Chalard and Pétillon2017a, Reference Ducasse, Renard, Pétillon, Costamagno, Foucher, Foucher and Caux2017b, Reference Ducasse, Pétillon, Chauvière, Renard, Lacrampe-Cuyaubère and Muth2019a, Reference Ducasse, Renard, Baumann, Castel, Chauvière, Peschaux and Pétillon2019b; Pétillon and Ducasse Reference Pétillon and Ducasse2012), the 2017–2018 Casserole dating program focused on direct 14C dating of culturally attributable bone and antler artifacts. Thus, based on the results of the typo-technological study of the site’s osseous industry (J.-M. Pétillon and F.-X. Chauvière), seven artifacts were selected for radiocarbon dating with respect to their (1) typo-technological interest, (2) position, both stratigraphic and planimetric and (3) state of preservation. As presented in Figures 2 and 3, these manufactured objects correspond to the following:

-

two antler flakes from the raclette-yielding Badegoulian levels (NA5 and NA4; Figure 2: artifacts #1 and 3) that are characteristic of the antler knapping technique documented in several “taphonomically controlled” Badegoulian assemblages in France (e.g. Allain et al. Reference Allain, Fritsch, Rigaud, Trotignon and Camps-Fabrer1974; Pétillon and Averbouh Reference Pétillon, Averbouh, Clottes, Giraud and Chalard2012);

-

an antler flake from level NA3 (Figure 2: artifact #2) that is characteristic of Badegoulian antler working manufacturing waste but that was recovered in a level with Magdalenian-like artifacts produced by the groove-and-splinter technique (GST). It is important to note that direct dating of diagnostic GST-produced artifacts has systematically shown that this technology is not associated with Badegoulian or Solutrean assemblages (e.g. Pétillon and Ducasse Reference Pétillon and Ducasse2012; Bourdier et al. Reference Bourdier, Pétillon, Chehmana, Valladas and Paillet2014; Raynal et al. Reference Raynal, Lafarge, Rémy, Delvigne, Guadelli, Costamagno, Le Gall, Daujeard, Vivent, Fernandes, Le Corre-Le Beux, Vernet, Bazile and Lefèvre2014; Chauvière et al. Reference Chauvière, Castel, Ducasse, Langlais and Renard2017; Ducasse et al. Reference Ducasse, Chauvière, Castel, Langlais, Aurière, Chalard and Pétillon2017a, Reference Ducasse, Renard, Pétillon, Costamagno, Foucher, Foucher and Caux2017b, Reference Ducasse, Pétillon, Chauvière, Renard, Lacrampe-Cuyaubère and Muth2019a);

-

an antler splinter from NA3 (Figure 2: artifact #4) showing edges of longitudinal grooves on both sides produced by the GST; direct dating would allow for an additional evaluation to test whether the GST and antler knapping technique were concomitant (see above);

-

an antler object from NA3 with a semi-circular cross-section (Figure 3: artifact #1), that is a likely “pseudo half-round rod” similar to those documented at the sites of Les Scilles, layer B (Pétillon et al. Reference Pétillon, Langlais, Beaune, Chauvière, Letourneux, Szmidt, Beukens and David2008; Pétillon in Langlais et al. Reference Langlais, Pétillon, Archambault de Beaune, Cattelain, Chauvière, Letourneux, Szmidt, Bellier, Beukens and David2010) and Le Petit Cloup Barrat, layer 4 (Chauvière in Ducasse et al. Reference Ducasse, Castel, Chauvière, Langlais, Camus, Morala and Turq2011), both of which contain specific assemblages associated with the transition between the Badegoulian and the Lower Magdalenian;

-

a bone fragment characteristic of Magdalenian-like GST manufacturing debris from the Central sector, layer 4 (Figure 3: artifact #3), but also correlated with level NA1 in the Eastern sector;

-

the base of a single-beveled bone point with a round cross-section from the Western sector, layer 4 (Figure 3: artifact #2), correlated with level NA9/10 of the Eastern sector. The typological features of this object are similar to those of the well-documented Final Gravettian/Protosolutrean single-beveled bone points described at Laugerie-Haute-Ouest, layer D and Laugerie-Haute-Est, layer 33 (Peyrony Reference Peyrony1929; Leroy-Prost Reference Leroy-Prost1975; Baumann Reference Baumann2014). It should also be noted that a blank on horse tibia, attributed to the manufacture of a similar point recovered from Layer D of the Abri des Harpons, has recently been dated to 27–26.2 cal ka BP (22,400 ± 150 BP; Ducasse et al. Reference Ducasse, Renard, Pétillon, Costamagno, Foucher, Foucher and Caux2017b).

Figure 2 Antler elements selected for AMS dating; 1, 2 and 3: flakes evidencing the use of the knapping technique from levels NA4, NA3 and NA5, respectively; 4: splinter from level NA3 evidencing the use of the groove and splinter technique. White letters in a black circle indicate the level and grey letters the label of the piece (photos J.-M. Pétillon, infographics S. Ducasse).

Figure 3 Bone and antler elements selected for AMS dating; 1: “pseudo antler half-round rod” from level NA3; 2: base of single beveled bone point from the Western sector, layer 4 (NA9/10?); 3: groove and splinter manufacturing bone waste from the Central sector (NA1?). White letters in a black circle indicate the level and grey letters the label of the piece (photos J.-M. Pétillon, infographics S. Ducasse).

Due to the fact that the osseous industry from NA6 (i.e. Early Badegoulian) is scarce (N=4 objects) and is poorly preserved, we selected two faunal remains among the best-preserved pieces (Table 5). The first is a diaphysis fragment of a humerus from an undetermined species, and the second is a fragment of a reindeer cotyloid cavity exhibiting 2 carnivore punctures. Although they do not show unequivocal anthropic modifications (e.g. cut-marks, etc.), these two remains can be easily considered as part of the NA6 anthropogenic assemblage since (1) they correspond to—or are compatible in size with—the principally exploited species documented in this level, (2) their fragmentation and size are similar to the rest of the assemblage, (3) they show a comparable and coherent state of preservation, and (4) the assemblage also contains several remains exhibiting pits and punctures made by small carnivores in association with cut-marks, suggesting one or more scavenging event(s) that disturbed the assemblage initially linked to human predation. While these two faunal remains were directly submitted to the laboratory to be sampled and dated, the first seven bone and antler artifacts (Figures 2 and 3) underwent a specific sampling procedure that served to preserve their main morphometric, typological and technological features. After a full photographic coverage of each piece, this procedure consisted of removing material via successive micro-drilling or by simply removing an unworked end (e.g. post-depositional fracture; for further details regarding this sampling method, see e.g. Pétillon and Ducasse Reference Pétillon and Ducasse2012; Ducasse et al. Reference Ducasse, Pétillon, Chauvière, Renard, Lacrampe-Cuyaubère and Muth2019a). Sampled masses ranged between 430 and 1000 mg.

Table 5 New ultrafiltered AMS 14C ages for the Badegoulian (NA6–NA4) and the so-called “Magdalenian” assemblages (NA3) and details of the failed samples from NA9/10 and NA1. Note that ages from NA6 (“GrM” lab code) were measured at the Groningen laboratory using a MICADAS accelerator mass spectrometer. Calibration was carried out with OxCal (v4.3.2: Bronk Ramsey Reference Bronk Ramsey2017) using the IntCal13 calibration curve (Reimer et al. Reference Reimer, Bard, Bayliss, Beck, Blackwell, Ramsey, Buck, Cheng, Edwards, Friedrich, Grootes, Guilderson, Haflidason, Hajdas, Hatté, Heaton, Hoffmann, Hogg, Hughen, Kaiser, Kromer, Manning, Niu, Reimer, Richards, Scott, Southon, Staff, Turney and Plicht2013).

All the samples were sent to the Lyon Carbon Dating Center (CDRC) for collagen extraction and ultrafiltration pretreatments following the methodologies outlined in Bronk Ramsey et al. (Reference Bronk Ramsey, Higham, Bowles and Hedges2004). Measurements were performed at either the Saclay laboratory (LMC 14; NA4 and NA3; in the framework the ARTEMIS program, see above) or the Center for Isotope Research in Groningen (CIR; NA6 and NA5), and the two samples from level NA6 were measured with the new Groningen MIni CArbon DAting System (MICADAS: e.g. Fewlass et al. Reference Fewlass, Talamo, Tuna, Fagault, Kromer, Hoffmann, Pangrazzi, Hublin and Bard2018). All the conventional ages were calibrated with OxCal (v4.3.2: Bronk Ramsey Reference Bronk Ramsey2017) using the IntCal13 calibration curve (Reimer et al. Reference Reimer, Bard, Bayliss, Beck, Blackwell, Ramsey, Buck, Cheng, Edwards, Friedrich, Grootes, Guilderson, Haflidason, Hajdas, Hatté, Heaton, Hoffmann, Hogg, Hughen, Kaiser, Kromer, Manning, Niu, Reimer, Richards, Scott, Southon, Staff, Turney and Plicht2013).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

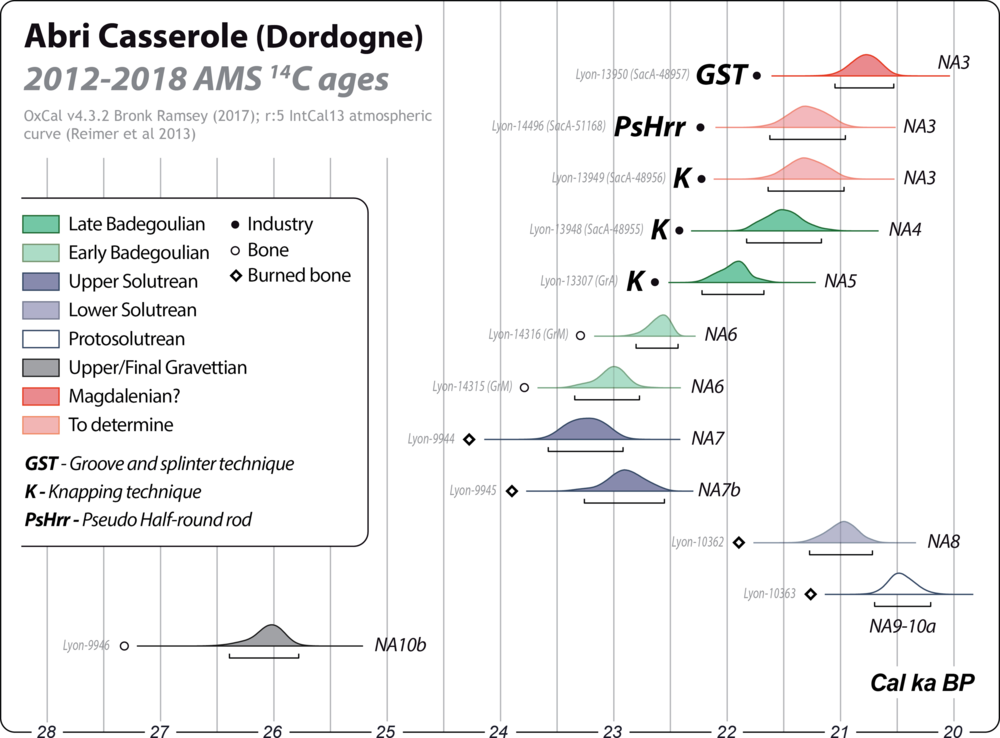

Seven samples were successfully dated. The other two samples—from Western and Central sectors and associated with levels NA9/10 and NA1, respectively—failed due to a low collagen yield (Table 5). While the failure of the NA1 sample (Figure 3, artifact #3; GST manufacturing waste) is mitigated by the age obtained for the GST splinter from NA3 (see below), the failure of the NA9/10 sample confirms the difficulty, if not the impossibility, to attribute a radiometric age to the Gravettian-to-Solutrean transition at Casserole and thus address the program’s third objective (see above). The seven successful samples encompass levels NA6 to NA3. They are highly consistent thereby allowing for a complete and robust chronology of the Badegoulian portion of the sequence, as well as an assessment of the homogeneity of the so-called Magdalenian levels (Table 5 and Figure 4).

Figure 4 Compilation of the 12 calibrated AMS 14C ages obtained between 2012 and 2018. Note the incoherent results obtained with burned bone samples from NA9-10a to NA7b (see discussion in the text).

Approximately 1000 Years Older: Restoring the Badegoulian Levels’ Chronological Coherence

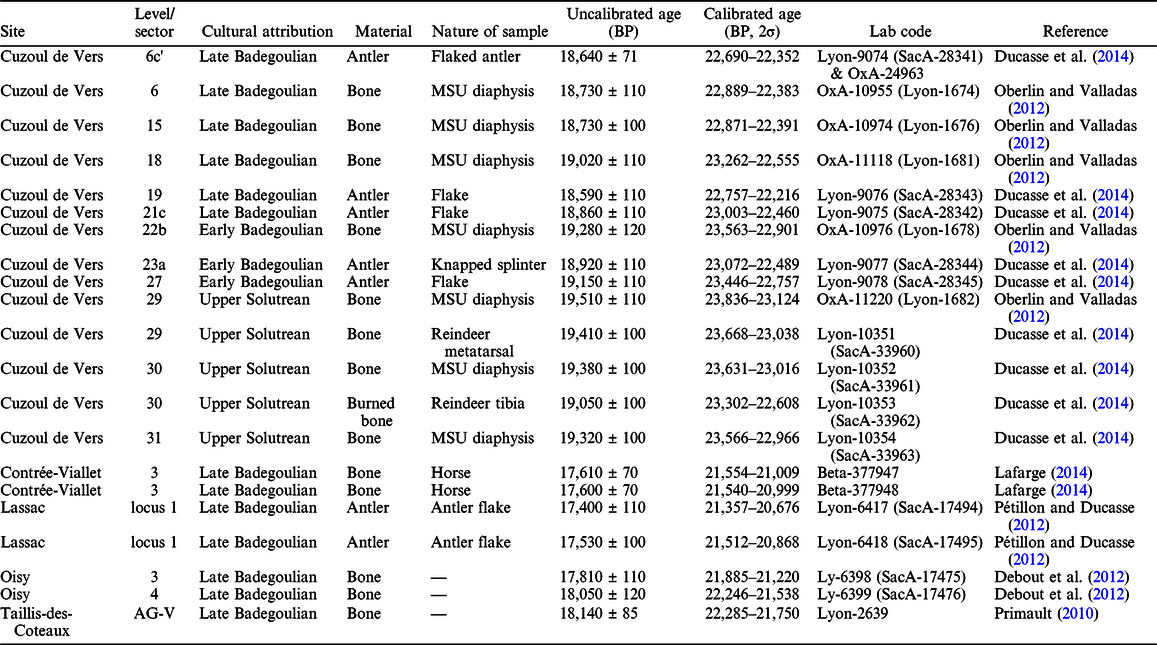

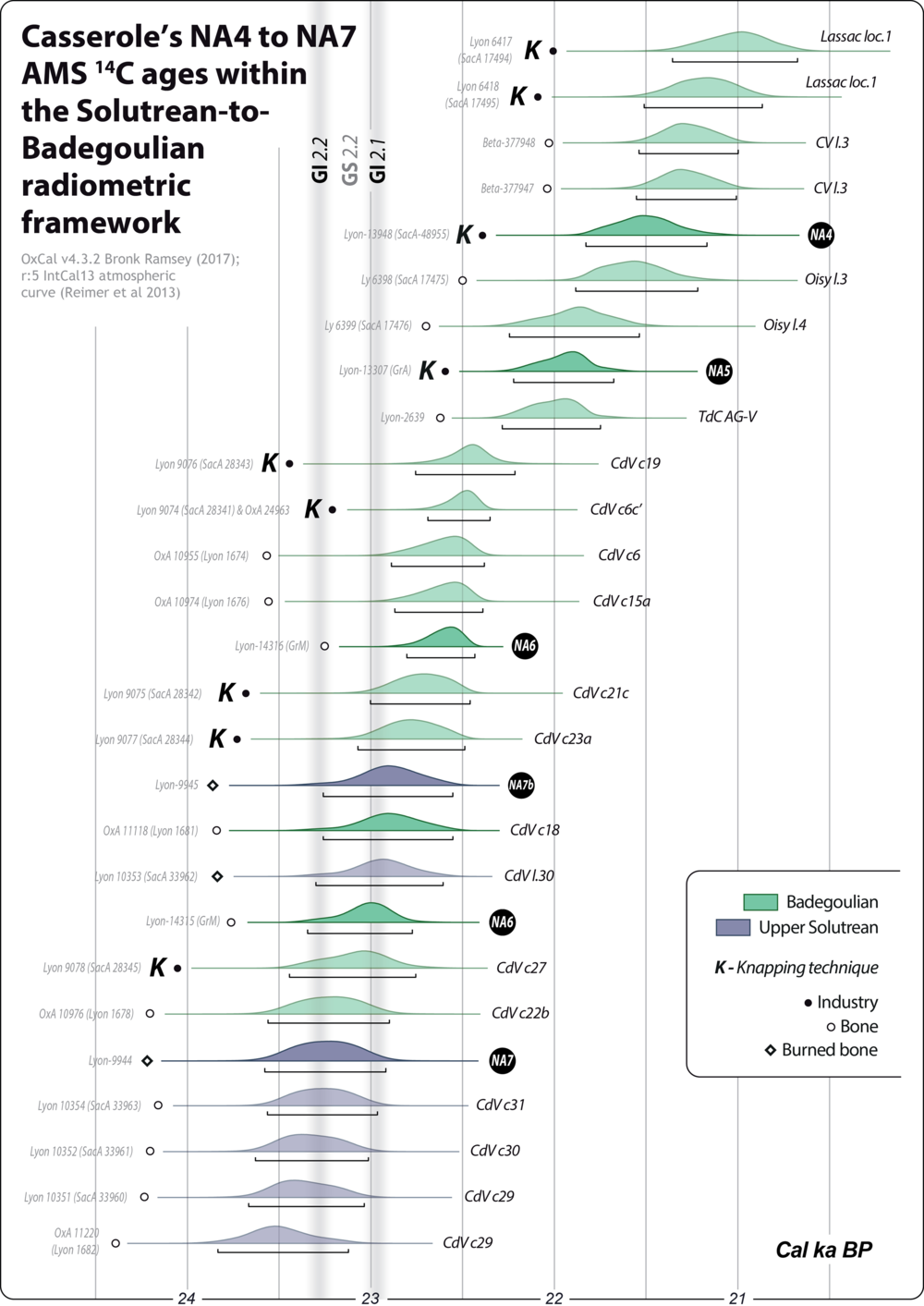

As expected, the AMS chronological time span obtained for the Badegoulian levels (i.e. NA6–NA4: Table 1) is approximately 1000 years older than the previous beta counting ages carried out in the 1990s. Once calibrated, the four stratigraphically well-ordered measurements fall within the 23.3–21.1 cal ka BP interval (NA6: 19,110 ± 70 BP: 23.3–22.7 cal ka BP; NA4: 17,760 ± 100 BP: 21.8–21.1 cal ka BP), thus covering the entire currently accepted Badegoulian AMS chronology (Banks et al. Reference Banks, Bertran, Ducasse, Klaric, Lanos, Renard and Mesa2019). These results serve to restore the chronological coherence of the Badegoulian sequence at Casserole and allow these assemblages to be reliably included in inter-site comparisons. This is notably the case of the Early Badegoulian assemblages documented in level NA6: along with the high level of typo-technological similarities between the Casserole NA6 Early Badegoulian lithic assemblages and those from Le Cuzoul de Vers levels 27–22 (Morala Reference Morala1993; Ducasse Reference Ducasse2010, Reference Ducasse2012), the new AMS ages define a highly similar chronological time span between 23.3–22.4 cal ka BP (Table 5 and 6; Figure 5). While some overlap exists between the oldest raclette-yielding Badegoulian ages and those for the terminal Upper Solutrean at the inter-regional scale, the radiometric data from Casserole serve to confirm the antiquity of the earliest expression of the Badegoulian in southwestern France for which Le Cuzoul de Vers had previously been the only example. Thus, these data place the Solutrean-to-Badegoulian transition at ca. 23 cal ka BP (Ducasse et al. Reference Ducasse, Pétillon and Renard2014, Reference Ducasse, Renard, Baumann, Castel, Chauvière, Peschaux and Pétillon2019b; Renard and Ducasse Reference Renard and Ducasse2015; Banks et al. Reference Banks, Bertran, Ducasse, Klaric, Lanos, Renard and Mesa2019).

Table 6 AMS 14C dates used in Figure 5 and covering the entire time span of the French Badegoulian, including the Solutrean-to-Badegoulian transition (MSU: medium-sized ungulate). Calibration was carried out with OxCal (v4.3.2: Bronk Ramsey Reference Bronk Ramsey2017) using the IntCal13 calibration curve (Reimer et al. Reference Reimer, Bard, Bayliss, Beck, Blackwell, Ramsey, Buck, Cheng, Edwards, Friedrich, Grootes, Guilderson, Haflidason, Hajdas, Hatté, Heaton, Hoffmann, Hogg, Hughen, Kaiser, Kromer, Manning, Niu, Reimer, Richards, Scott, Southon, Staff, Turney and Plicht2013).

Figure 5 The NA4 to NA7 ages compared with a selection of AMS 14C dates covering the entire time span of the French Badegoulian, including the Solutrean-to-Badegoulian transition phase (CdV: Cuzoul de Vers; CV: Contrée-Viallet; TdC: Taillis-des-Coteaux). Note that the too-young Upper Solutrean age available for Le Cuzoul de Vers layer 30 corresponds to a burned bone sample (see Ducasse et al. Reference Ducasse, Pétillon and Renard2014 for a detailed discussion).

The assemblages from levels NA5 and NA4, both attributed to the classic raclette-yielding Badegoulian (Morala Reference Morala1993), produced two ages from directly dated antler flakes: 18,100 ± 80 BP (22.2–21.6 cal ka BP) and 17,760 ± 100 BP (21.8–21.1 cal ka BP), respectively (Table 5). Although they appear younger than those from Le Cuzoul de Vers layers 21–6 (Figure 5), they fit perfectly with other extra-regional data (e.g. Lassac, locus 1: Pétillon and Ducasse Reference Pétillon and Ducasse2012; Oisy, layer 3 and 4: Debout et al. Reference Debout, Olive, Bignon, Bodu, Chehmana and Valentin2012; Taillis-des-Coteaux, AG-V: Primault Reference Primault2010). Documenting the 22–21 cal ka BP time span that corresponds to the second and final portion of the currently recognized Badegoulian chronology, these ages show virtually no overlap with those associated with the Early Badegoulian (Figure 4).

An inter-layer refitting program demonstrated the absence of clear post-depositional mixing between the Early and Late Badegoulian levels (NA6 versus NA5/4) as well as between the latter and the Magdalenian levels NA3–NA1 (ongoing monograph publication). Consequently, taphonomic reasons cannot be proposed to explain the strong differences between beta counting and AMS results (i.e. the younger beta counting ages cannot be due to intrusive Magdalenian artifacts). Thus, in addition to technical and material differences between the two dating methods, we must also consider a combination of methodological causes, among them the nature of the dated sample (bulk bone sample versus a single artifact) and the use of distinct pretreatments techniques (ABA method versus ultrafiltration). It is important to point out that ultrafiltration pretreatment alone cannot explain this situation since there exist several examples of twice-dated artifacts from Last Glacial Maximum (LGM) assemblages whose ultrafiltered and non-ultrafiltered ages from separate laboratories are highly comparable (e.g. Le Cuzoul de Vers: Ducasse et al. Reference Ducasse, Pétillon and Renard2014; Grand Abri de Cabrerets: Ducasse et al. Reference Ducasse, Renard, Baumann, Castel, Chauvière, Peschaux and Pétillon2019b). Finally, as already recommended for Le Cuzoul de Vers (Ducasse et al. Reference Ducasse, Pétillon and Renard2014), the use of previous beta counting measurements is to be avoided in the case of Casserole as they clearly underestimate the true ages of the dated samples.

The Cultural Attribution of NA3: Chronocultural Admixture and Transitional Industry

In parallel with the typo-technological reassessment of the lithic and osseous industries, the second objective of this new dating program was to evaluate the chronocultural attribution of the so-called Magdalenian levels (NA3–NA1). Due to the fact that a unique and non-characteristic worked antler artifact was recovered from NA2 (Pétillon and Chauvière, unpublished) and because the sample from the Western sector, correlated to NA1, could not be dated due to a low collagen yield (see above), the contribution of radiometric data to addressing this issue concerns only level NA3. The obtained ages (Table 5) confirm the mixing of material from different cultural contexts, as suggested by previous observations of Magdalenian-like and Badegoulian-like artifacts grouped together in this level (i.e. raclettes, microbladelet debitage, antler flakes and GST manufacturing waste: op. cit. and Langlais, unpublished), as well as inter-layer refits, such as between NA4 (Late Badegoulian: Table 1) and NA3. The Lyon-13950 (SacA-48957) age minimally overlaps with the others from NA3 and NA4 (Figure 4), thus demonstrating clear chronocultural admixture between the two levels and further serves to invalidate any proposed archaeological association between the antler knapping technique (antler flake: 17,620 ± 100 BP: 21.6–21 cal ka BP) and the GST (17,230 ± 90 BP: 21–20.5 cal ka BP) in LGM contexts (Pétillon and Ducasse Reference Pétillon and Ducasse2012). However, it should be noted that, excluding the Gravettian examples (Goutas Reference Goutas2009), the latter result corresponds to one of the oldest direct-dated GST artifact and is comparable to an age obtained previously at the Abri Reverdit, Dordogne (17,180 ± 110 BP: 21–20.4 cal ka BP, GifA-10115/SacA-19771; Bourdier et al. Reference Bourdier, Pétillon, Chehmana, Valladas and Paillet2014).

The antler half-round section piece (Figure 3, artifact #1) produced a Badegoulian-like age (17,610 ± 100 BP: 21.6–21 cal ka BP) similar to that from the antler flake. According to current knowledge, this chronological interval and typo-technological association correspond to both Late Badegoulian (e.g. Lassac, locus 1: 17,530 ± 100 BP: 21.5–20.8 cal ka BP, Pétillon and Ducasse Reference Pétillon and Ducasse2012; La Contrée-Viallet, layer 3: 17,610 ± 70 BP: 21,5–21 cal ka BP, Lafarge Reference Lafarge2014) and certain Badegoulian-to-Magdalenian transition assemblages containing lamelles à dos dextre marginal (LDDM; Langlais et al. Reference Langlais, Pétillon, Archambault de Beaune, Cattelain, Chauvière, Letourneux, Szmidt, Bellier, Beukens and David2010; Ducasse et al. Reference Ducasse, Castel, Chauvière, Langlais, Camus, Morala and Turq2011, Reference Ducasse, Pétillon, Chauvière, Renard, Lacrampe-Cuyaubère and Muth2019a, Langlais et al. Reference Langlais, Sécher, Laroulandie, Mallye, Pétillon and Royer2018; Langlais et al. Reference Langlais, Delvigne, Jacquier, Lenoble, Beauval, Peschaux, Ortega Fernandez, Lesvignes, Lacrampe-Cuyaubere, Bismuth and Pesesse2019; Primault et al. Reference Primault, Brou, Bouché, Catteau, Gaussein, Gioé, Griggo Ch, Le Fillatre and Peschaux2020). These transitional assemblages are currently the object of a chronological and typo-technological characterization program being conducted in the framework of the DEX_TER project (S. Ducasse and M. Langlais coord.). While LDDM may exist in level NA3 of Casserole (Langlais, unpublished observations; Detrain et al. Reference Detrain, Kervazo, Aubry, Bourguignon, Guadelli, Marcon and Teillet1991: 88), it is difficult at present to demonstrate this unequivocally since: (1) NA3/NA2 correspond to very small and mixed assemblages (see above); and (2) the ages obtained on the “pseudo half-round rod” and the antler flake from NA3 fall within the same chronological interval as the antler flake from the Late Badegoulian level NA4 (see above, Table 5 and Figure 4: 21.8–21 cal ka BP), and both levels contain typical Badegoulian raclettes. Together with the typo-technological data, these results highlight the already recognized taphonomic complexity of the uppermost levels (Detrain et al. Reference Detrain, Kervazo, Aubry, Bourguignon, Guadelli, Marcon and Teillet1991, Reference Detrain, Aubry, Beyer, Bidart, Bourguignon, Diot, Guadelli, Kervazo, Legrand, Leroyer, Limondin, Marcon, Morala, Platel and Rouzo1992) and demonstrate the need for additional studies that are beyond the scope of the present paper.

CONCLUSION

Although the results of this third dating program failed to resolve the question concerning the Protosolutrean chronology, they serve to shed new light on the radiometric framework of the well-known but understudied Badegoulian portion of the sequence. Combined with the 2012 program, these results provide new data with which to examine the chronology of the Solutrean-to-Badegoulian transition in southwestern France. The first AMS ages obtained from levels NA6–NA4 are entirely consistent with other key, extra-regional sites, such as Le Cuzoul de Vers (Lot), Le Taillis-des-Coteaux (Vienne) and Lassac, locus 1 (Aude), and they allow one to discard the 1990s beta counting measurements and establish an updated and accurate chronology for the Abri Casserole. The case of Casserole demonstrates the importance of conducting any dating campaign in conjunction with detailed archaeostratigraphic studies, since the latter serve to interpret the former adequately. In this vein, it would be worthwhile to confirm the chronological position and homogeneity of the single-dated NA5 and NA4 levels (Late Badegoulian) and to test the archaeological reality of the long-term occupation documented for NA6 (Early Badegoulian). Despite the high typo-technological homogeneity of the assemblages, the latter question needs to be addressed in conjunction with an inter-layer refitting program involving the Upper Solutrean assemblages from level NA7 in order to evaluate whether that portion of the sequence has been affected by post-depositional processes.

Finally, beyond the archaeological interest of these new AMS results that effectively challenge and complement previously available radiometric data, this contribution simultaneously and indirectly addresses several recurrent methodological issues, such as: (1) the comparability of 14C AMS and beta counting results, (2) the reliability of ages from burned bones, (3) the potential influences of different pretreatment processes; and, even if it is preaching to the choir, (4) the importance of correctly using, reproducing, and citing 14C data (see Table 3). The combination of some or all of the above elements can dramatically blur the intra- and inter-site comparability of radiocarbon frameworks and, in doing so, skew the chronological models and anthropological inferences that are based upon them.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Jean-Jacques Cleyet-Merle, director of the MNP, for granting us access to the Casserole collections and for providing sampling authorizations. We also thank Michel Fontugne for providing information about the Modane dating process and to Christine Oblerlin and the CDRC laboratory of Lyon for the quality of support during the dating process. We also thank the two anonymous reviewers whose comments served to strengthen the paper. This research was carried out as part of the Casserole monograph project (Lenoble and Detrain dir.) and the IMPACT project (Banks dir.), funded by the Direction Regionale des Affaires Culturelles de Nouvelle Aquitaine (Ministère de la Culture et de la Communication) and the LabEx Cluster of Excellence “LaScArBx” (ANR-10-LABX-52), respectively.