INTRODUCTION

Radiocarbon dating of historic manuscripts and documents represents a useful tool in archeological, historic, and paleographic studies. Absolute dating is only possible if the manuscript has a colophon, meaning a statement given in the manuscript’s text, typically written by the copyist or the author, giving information about the time, place, and circumstances of the manuscript’s production. Without colophons, or when there are doubts about their authenticity, all date estimates depend on philological methods, such as linguistic analysis, that is comparing the developments in language vocabulary, form and style, historical analysis like finding references to the historical features, events, or other dated sources in the text, and paleography which is based on the historical development of letter shapes. Paleography argues that shapes and styles of a script change over time, that the change in letter shapes reflects chronology. Because paleographic and philological date estimates depend on comparison, they produce “relative chronology,” reflecting the experience and evaluation of the scholar who pronounces them. Scientific analysis (radiocarbon dating) offers firm grounds for the dating of the writing surface to overcome the divide between dating by colophons and relative chronology by paleography and philology. The potential of radiocarbon dating has been recognized since the very early days of the method, which nearly coincided with the discovery of Dead Sea Scrolls (Sellers Reference Sellers1951). However, the early radiocarbon dating of precious manuscripts was limited by the size of required samples, measured in grams of parchment and paper. In the earliest study (Berger et al. Reference Berger, Evans, Abell and Resnik1972), the radiocarbon technique was applied by using samples as large as 5–12 g taken from parchment.

The situation changed in the late 1970s after the development of the accelerator mass spectrometry (AMS) method (Bennett et al. Reference Bennett, Beukens, Clover, Gove, Liebert, Litherland, Purser and Sondheim1977). The downscaling of sample size from grams to milligrams revolutionized application of RD to studies of precious artifacts and historic objects of cultural heritage, including manuscripts and books. One of the first, most extensive studies, was the dating of the Dead Sea Scrolls (Bonani et al. Reference Bonani, Ivy, Wolfli, Broshi, Carmi and Strugnell1992) or scrolls from the Judean Desert (Jull et al. Reference Jull, Donahue, Broshi and Tov1995). More studies followed, including dating medieval manuscripts from the University of Seville (Santos et al. Reference Santos, Gómez-Martínez and García-León2010), dating ancient Japanese calligraphy sheets (Oda et al. Reference Oda, Yasu, Ikeda, Sakamoto and Yoshizawa2011), the Torah scrolls (Oliveira et al. Reference Oliveira, Araujo, Macario and Cid2015) or Early Islamic Documents (Youssef-Grob Reference Youssef-Grob2019). More recent developments of treatment techniques focus on removing contamination and retaining the maximum amount of original carbon so as to minimize the required sample amount (Brock Reference Brock2013; Brock et al. Reference Brock, Dee, Hughes, Snoeck, Staff and Ramsey2018; Kasso et al. Reference Kasso, Oinonen, Mizohata, Tahkokallio and Heikkilä2021). The precise and accurate radiocarbon dating of manuscripts is essential because historic and paleographic studies require high-precision age estimates. This precision can only be achieved with a sufficient amount of carbon analyzed as a sample (Hajdas et al. Reference Hajdas, Ascough, Garnett, Fallon, Pearson, Quarta, Spalding, Yamaguchi and Yoneda2021). Radiocarbon analysis has been applied for studying and dating Qur’an manuscripts since the late 1990s (von Bothmer Reference von Bothmer, Ohlig and Puin1999). Some researchers express concern about the techniques of the analysis, as the results did not entirely fit their expectations. In some cases, these researchers claimed that the final say should remain with the historian or the specialist in paleography—not with the scientist (e.g., von Bothmer Reference von Bothmer, Ohlig and Puin1999:45; Déroche Reference Déroche2014:12–13). As some scholars are convinced that the text of the Qurʾān took its final shape after Muhammad (d. 632) and that it was subject to redactional processes (Dye Reference Dye2019), the discussion about the value of radiocarbon dating continues. In a book published recently, Stephen Shoemaker (Reference Shoemaker2022) discusses radiocarbon in detail from a philological and historiographical perspective for early Islamic documents. Many of his notes rightly point to open debates within the community of Qurʾān researchers. However, he disregards (or cannot resolve) the problem that triggered the interest in applying 14C-dating to Qurʾānic manuscripts in the first place: early Qurʾān manuscripts cannot be sufficiently dated by paleography, philology or the study of colophons, obscuring their age. We are convinced and stay optimistic that with a growing number of analyzed samples from Oriental and Qurʾānic manuscripts (Aghaei and Marx Reference Aghaei and Marx2021), radiocarbon dating will prove its significance as in the course of time it finds growing acceptance in field of manuscript studies.

This paper presents the results of the radiocarbon dating campaign carried out in the project “Irankoran” directed by Ali Aghaei (funded by the Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung, BMBF, Germany and the Berlin-Brandenburgische Akademie der Wissenschaften, BBAW, Berlin/Potsdam; for an introduction to the project, see Aghaei Reference Aghaei2020) at the Central Library of the University of Tehran (CLUT). During the last years, the project “Corpus Coranicum” (BBAW; for an introduction to the project, see https://corpuscoranicum.de/about) has undertaken systematic approaches for dating of manuscripts through radiocarbon dating (see Marx and Jocham Reference Marx and Jocham2019). Previous campaigns carried out by a group of French and German scholars in two research projects “Coranica” (funded by Agence Nationale de la Recherche, ANR and Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft, DFG) and “Paleocoran” (funded by Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft, DFG directed by F. Déroche and M. Marx), focused on the first millennium. These studies identified five larger fragments on parchment written before 700 and seven fragments dated to the period between 700 and 800 (Marx and Jocham Reference Marx and Jocham2019); measurements of samples presented here only contain one manuscript dated before the year 1000 CE, an ancient fragment of the Qurʾān on parchment (#10950). Thus, the following results offer perspectives on documents mainly from the second millennium. Since the dating of some documents has been subject of discussions and disputes, the results of 14C presented here can help enhance our understanding of their history. We also hope that results of our campaign will give an incentive to apply scientific dating to other philological fields on the one hand, and to attract the attention of scholars in physics to the potential that these measurements have for the improvement of the technique as well as its application on philology on the other hand. We provide in the following pages a short description of each manuscript from which the samples for the 14C analysis have been taken. In the description we elaborate the debates about the dates of the selected manuscripts to clarify how the additional information provided by 14C-dating will advance the historical/philological discussion.

DESCRIPTIVE BACKGROUND

In January 2019, within the framework of the Memorandum of Understanding between CLUT and BBAW (signed on November 20, 2018) and after the registration and signing of contracts prepared for the dating campaign, samples from six manuscripts were taken and sent to the Ion Beam Physics laboratory at the ETH Zurich for radiocarbon dating. The selected manuscripts consist of one quite old Qurʾān fragment on parchment (#10950) and a selection of valuable and diverse manuscripts from Iranian and Islamic heritage, including the Arabic dictionary Muǧmal al-Luġah (Meškāt #203), the medical encyclopedia Ḏaḫīrah-ye Kh w ārazmšāhī (#5156), the poetry Panǧ Ganǧ of Neẓāmī (#5179), Ādāb al-Falāsifah (#2165) attributed to Syriac scholar Ḥunayn b. Isḥāq (d. 873 CE), and one of the oldest versions of the Avesta Wīdēwdād (#11263). The selection of pages from which samples were taken was determined in discussion with the curator of the institution. It was of primary concern not to damage parts of the manuscripts that contain text. All samples were taken from the margin in a way that the damage of sample taking would not strike the reader of the manuscript.

MATERIAL

Qurʾān Parchment, CLUT #10950

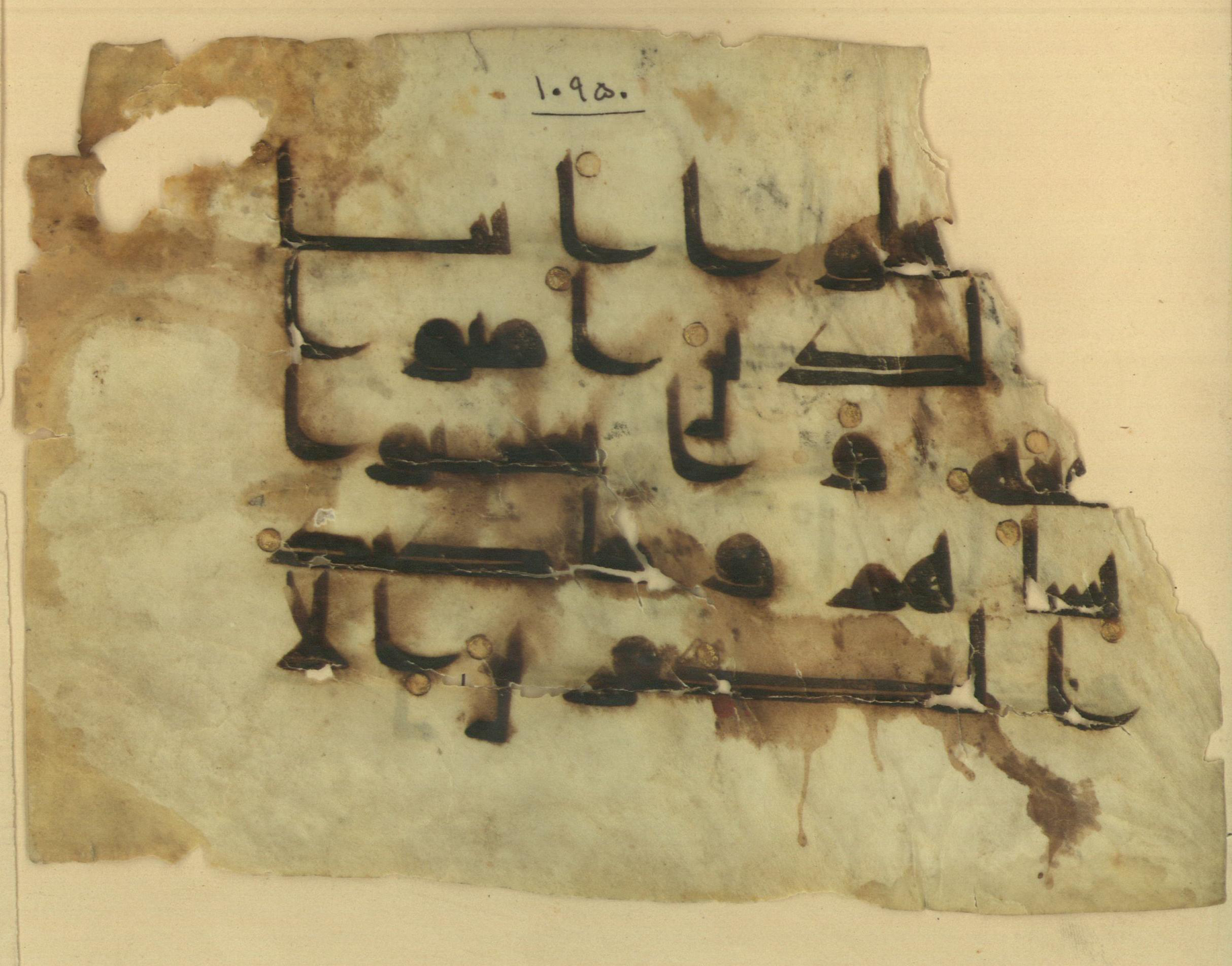

Folio #10950, a parchment leaf of an ancient kūfī Qurʾān (dimensions 14.5 × 20 cm, text area 9 × 14.5 cm, covering Q 40:25–26), has been exposed to humidity and part of its margin is destroyed (Hakim Reference Hakim2010:536; see Figure 1). A sister fragment of this leaf is kept in the Khalili Collection, London, whose writing style has been identified by Déroche (Reference Déroche1992:70) as D.1 according to his paleographical classification of early Qurʾānic scripts (see also Déroche Reference Déroche1983, Reference Déroche2014).

Figure 1 Qurʾān Parchment #10950, recto.

Manuscript of Muǧmal al-Luġah, CLUT Meškāt #203

Of the numerous, worldwide attested copies, the manuscript in CLUT registered under shelfmark Meškāt #203 (257 fols., paper with beige colour, dimensions 15 × 20 cm, text area 10 × 15 cm) appears to be the most ancient copy of Muǧmal al-Luġah written by Abu al-Ḥusayn Aḥmad Ibn Fāris (d. 395 AH/1004 CE; for more about him see Fleisch Reference Fleisch1968), since its colophon dates it to 479 AH/1086 CE (Monzavī Reference Monzavī1953:447–448). This copy was written for a person named Abu al-Ḫayr Naṣr ibn ʿAlī ibn al-Ḥusayn ibn Naṣr al-ʾAzdī (see Figure 2). The copyist’s name is only mentioned at the end of the book devoted to the letter lām: faraġa min katbihī Hibatallāh ibn al-Ḥusayn ibn ʾAḥmad al-Qaṣbarī fī šahr allāh al-mubārak sanat tisʿ wa-sabʿīn wa-arbaʿ miʾah, “Hibatallāh ibn al-Ḥusayn ibn ʾAḥmad al-Qaṣbarī finished writing the book in the blessed month of God of the year four hundred and seventy-nine” (folio 121v).

Figure 2 Muǧmal al-Luġah, Meškāt #203; fol. 27v, the end of kitāb al-fāʾ. The colophon reads: faraġa min katbihī ġarrata šahr allāh al-mubārak sanat tisʿ wa-sabʿīn wa-arbaʿ miʾah. “He finished writing the book at the beginning of the blessed month of God in the year four hundred and seventy-nine.”

Manuscript of Ḏaḫīrah-ye Kh w ārazmšāhī, CLUT #5156

Ḏaḫīrah-ye Kh w ārazmšāhī is a comprehensive Persian medical encyclopedia (see Saʿīdī Sīrjānī 1993; Matīn Reference Matīn2013), written by al-Sayyid Ismāʾīl al-Ǧurǧānī (or Gorgānī, d. 531 AH/1137 CE; about him see Qāsemlū Reference Qāsemlū2006). It was presented to the governor of Khwārazm, Quṭb al-Dīn Muḥammad Khwārazmšāh (r. 490–521/1097–1127). There are numerous copies of the book (see Derāyatī Reference Derāyatī2012:53–74), the oldest one is CLUT #5156 (413 fols., paper, dimensions 31 × 44 cm, text area 22 × 32 cm), dating back to 582 AH/1186 CE (Dānešpajūh Reference Dānešpajūh1966:4129). Since the first figure of the date in the colophon seems to have been removed and rewritten (see Figure 3), it has led to doubts about the manuscript’s original date (Dānešpajūh Reference Dānešpajūh1966; cf. Ǧorǧānī Reference Ǧorǧānī2011, editor’s introduction: 14).

Figure 3 Ḏaḫīrah-ye Khwārazmšāhī, CLUT #5156. The colophon reads: faraġa minhu kātibihī yaum al-ǧumʿa as-sābiʿ ʿašar šahr šawwāl sanat iṯnay wa-sabʿīn wa-ṯamānīn wa-ḫams miʾah. “Its copyist finished the book on Friday 17th of the month šawwāl of the year five hundred and eighty-two.”

Manuscript of Panǧ Ganǧ by Neẓāmī Ganǧawī, CLUT #5179

Ḫamseh-ye Neẓāmī (“Pentalology of Neẓāmī”) or Panǧ Ganǧ (“Five Treasures”) is an anthology from Neẓāmī-ye Ganǧawī (d. 605 AH/1209 CE), one of the founding fathers of Persian epic tradition (about him see Chelkowski Reference Chelkowski1995). As the book title says, it consists of five parts (in the maṯnawī form): Maḫzan al-Asrār (“Storehouse of Secrets,” 2260 verses), Ḫosrow wa Šīrīn (6500 verses), Leylī wa Maǧnūn (4600 verses), Haft Peykar (“Seven Battles,” 5130 verses), and Eskandarnāmeh (“Alexander Romance,” consisting of two parts, Šarafnāmeh and Eqbālnāmeh, 10500 verses in total). Manuscripts of Neẓāmī’s pentalogy— attested in collections in Iran and around the globe—are known for their magnificent illustrations. The oldest dated manuscript of the entire Ḫamseh, dates back to 763 AH/1362 CE and is preserved in manuscript Supplément persan 1817 of the Bibliothèque Nationale de France (Domenico Parrello Reference Parrello2000).

While CLUT #5179 (179 fols., paper, dimensions 21 × 30 cm, text area 14 × 22 cm) contains only Eskandarnāmeh, Haft Peykar (“Seven Battles”), and Leylī wa-Maǧnūn, it appears to be the oldest dated copy of Neẓāmī’s epic works. In the colophon (folio 176r; see Figure 4) the scribe gives the date for the completion of this splendid paper manuscript as 718 AH, corresponding to 1318 CE (Dānešpajūh Reference Dānešpajūh1966:4139; for a laboratorial analysis of materials and compounds in this manuscript, see Kordavani et al. Reference Kordavani, Bahadori and Bahrololumi2018). This unique Tehran copy of Panǧ Ganǧ was registered in 2010 in the UNESCO Memory of the World Register.Footnote 1

Figure 4 Panǧ Ganǧ, CLUT #5179. The colophon reads: faraġa min taḥrīt hāḏa al-kitāb bi-ʿaun allāh wa-ḥusn taufīqihī wa-ṣ-ṣalāt wa-s-salām ʿalā rasūlihī Muḥammad wa-ālihī aǧmaʿīn wa-sallama taslīman (fī šuhūr sanat ṯaman ʿašar wa-sabʿ miʾah). “He finished writing this book with the help of God and His good support, and blessing and peace be upon His Messenger Muḥammad and his entire Family (in the months of the year seven hundred and eighteen AH).

Manuscript of Ādāb al-Falāsifah, CLUT #2165

Ḥunayn ibn Isḥāq (d. 260 AH/873 CE) was a 9th century Bagdad-based scholar of Arabic sciences, whose translations from Greek to Arabic (often via Syriac translations of the Greek) were fundamental to the spread of Greek heritage in the Arab empire (Hāšemī Reference Hāšemī2010). His book Nawādīr alfāẓ al-falāsīfah al-ḥukamāʾ wa-ādāb al-muʿallimīn al-qudamaʾ (“Anthology of Sayings of Litterateurs and Ancient Teachers”), commonly known under its short name Ādāb al-falāsifah (“Culture of the Philosophers”) consists of sayings and parables from the wise ancients, of which an abridgement (and not the original work) is published by ʿAlī ibn Ibrāhīm al-Anṣārī (Ḥunayn ibn Isḥāq 1985). Manuscript CLUT #2165, named Ādāb al-falāsifah (51 fols., paper, dimensions 13 × 28 cm, text area 9 × 14 cm; see Dānešpajūh Reference Dānešpajūh1961:858) is attributed to Ḥunayn ibn Isḥāq. While the relationship between this manuscript and the potential holograph of Ḥunayn’s Nawādīr was not clear, at least to Dānešpajūh (Reference Dānešpajūh1961; cf. Cottrell Reference Cottrell2020, with an edition and a study of the text showing its parallels and references), at two instances in the manuscript it is stated that Ḥunayn ibn Isḥāq wrote the Arabic text himself. The colophons state that the manuscript includes the introductory treatise and the first part of the book, finished by Ḥunayn ibn Isḥāq in 249 AH/871 CE (see Figures 5a and 5b). Taking these statements at face value would make CLUT #2165 one of the oldest dated manuscripts in the world, reaching back to Baghdad of the 9th century (ʿAwwād 1982:77; Sāmirrāʾī 2001:180, note 3). However, there are some doubts regarding the authenticity of this copy (Frye Reference Frye and Richard1974:106–109; al-Badawī in his introduction to Ḥunayn ibn Isḥāq 1985:10; Déroche Reference Déroche1987–1989:350).

Figure 5a Ādāb al-Falāsifah, CLUT #2165, fol. 25v. The colophon at the end of the starting treatise reads: tammat ar-risālah wa-katabahā Ḥunayn ibn Isḥāq al-ʿIbādī, “The treatise was done and written by Ḥunayn ibn Isḥāq al-ʿIbādī.”

Figure 5b Ādāb al-Falāsifah, CLUT #2165, fol. 51v. The colophon at the end of the first part reads: tammat al-ǧuzʾ al-awwal min Kitāb Ādāb al-falāsifah wa-katabahū Ḥunayn ibn Isḥāq aṭ-Ṭabīb al-ʿIbādī fī ḏī al-ḥiǧǧah min sanat tisʿ wa-arbaʿīn wa-miʾatayn min al-hiǧrah, “The first part of the book of Ādāb al-falāsifah, was accomplished and written by the physician Ḥunayn ibn Isḥāq al-ʿIbādī, on ḏū al-ḥiǧǧah in the year 249 AH.”

Manuscript of Wīdēwdād, CLUT #11263

Wīdēwdād, from Middle Persian or Pahlavi, Vî-Daêvô-Dāta (“anti-demon law”), is one of the five chapters of today’s extant Avesta (the Zoroastrian holy text; see Tafaḍḍolī Reference Tafaḍḍolī1997:60–61; Āmūzgār Reference Āmūzgār2002, Translator’s preface: 27–28; Karam-Reḍāʾī 2015:319–320). There are numerous copies of Wīdēwdād in collections in Iran and outside (Andrés-Toledo and Cantera Reference Andrés-Toledo, Cantera and Cantera2012). Manuscript CLUT #11263 (293 fols., dimensions 37.5 × 24.5 cm, text area 28 × 15 cm) is one of the oldest copies of Wīdēwdād in the world, and one of the two oldest copies in Iran (Karam-Reḍāʾī 2015:324; see Mazdāpūr Reference Mazdāpūr2002:10–11, Reference Mazdāpūr2013; see also Andrés-Toledo and Cantera Reference Andrés-Toledo, Cantera and Cantera2012:208–209). A facsimile of this manuscript has been published by Afšār and Mazdāpūr (Reference Afšār and Mazdāpūr2013). The copyist, Frēdōn Marzbān, wrote the manuscript in the town Šarīf Ābād (Yazd), in 976 of Yazdegerd’s Era/1607 CE (about the Era of Yazdegerd, see Taqizadeh Reference Taqizadeh1939). The memos at the middle and end of the book in Pahlavi language provide complete information about the time and location of writing, the copyist’s name, and the commissioner (Mazdāpūr Reference Mazdāpūr2002:10; Reference Mazdāpūr2013:47–48):

“… I, the servant of the religion (dēn-bandag), Frēdōn Marzbān Frēdōn Wahrom Rustam Bondār Šahmardān Dēnayār, wrote and finished with success and happiness, on the 24th (rōz ī dēn) of the month of Ḫordād of the year 976, after twenty years of Yazdegerd the king, the grandson of Ḫosraw, the king of Ohrmazdān … I wrote this Jud-dēw-dād (=Wīdēwdād) by order of… Adurbād Māhwindād Hōšang Siyāwaḫš …” (folio 160r);

“… I, the servant of the religion, Frēdōn Marzbān Frēdōn Wahrom Rustam Bondār Šahmardān Dēnayār, wrote” (folio 295v) “… with success and happiness, on the 29th (rōz ī mānsaraspand) of the month of Tīr of the year 976, after twenty years of Yazdegerd the king of Ohrmazdān, from the lineage of Ḫosraw, the king … I wrote this Jud-dēw-dād in the land of Iran, in the village Šarafābād Štahnawed Maybod of Yazd, in the house of Wahrom Rustam Bondār …” (folio 296r).

The dates have been tampered with in both colophons in Persian, attempting to make the copy seem older by changing “nine hundred” to “seven hundred” (Afšār Reference Afšār2013:14, note 19 and 16, note 31; Mazdāpūr Reference Mazdāpūr2013:22; for more detailed discussions on the date of this manuscript, see Mazdāpūr Reference Mazdāpūr2013:22–26; see Figures 6a and 6b).

Figure 6a Wīdēwdād, CLUT #11263, fol. 160v. The colophon in Persian reads: tamāmat šod īn yašt dar rūz-e dīn hamān māh-e ḫordād būd az yaqīn ze tārīḫ Yazdgerd haftād o šeš bod o nohṣad-e dīgar ey mard-e hoš “This yašt ended on the day of religion (dīn). It was on the month of ḫordād for sure. It was seventy-six years, and nine hundred years more after Yazdegerd[’s coronation], O sober man!”

Figure 6b Wīdēwdād, CLUT #11263, fol. 297v. The colophon in Persian reads: […] ke īn daftar be manzel resānīdīm o gašte šādmān del tamāmat gašt īn daftar be taqdīr […] sanah bod nohṣad o haftād bā šeš ze Yazdgerd … “I brought this book to the home (end) and the heart became full of joy. The book is completed as it was destined [to be]. […] It was nine hundred and seventy-six years after Yazdegerd[’s coronation].”

RADIOCARBON DATING

The starting mass of samples was on the order of ca. 10–20 mg. Samples of paper and parchment were treated using solvents to remove contamination with oils and waxes and with acid and base (ABA) to remove carbonates and humic acids (Hajdas Reference Hajdas2008; Hajdas et al. Reference Hajdas, Ascough, Garnett, Fallon, Pearson, Quarta, Spalding, Yamaguchi and Yoneda2021). The purified samples were dried and ca. 2–3 mg of parchment or paper was placed in the Zn cups for a combustion in an Elemental Analyser and subsequent graphitization in the AGE system (Nemec et al. Reference Nemec, Wacker and Gaggeler2010). The graphitized samples were then pressed into the aluminium cathodes and measured using the MICADAS system at the ETH facility (Synal et al. Reference Synal, Stocker and Suter2007).

The measured values F14C (Reimer et al. Reference Reimer, Brown and Reimer2004), corrected for blank and normalized to the OXA II standard were converted to conventional radiocarbon ages (Stuiver and Polach Reference Stuiver and Polach1977). Radiocarbon ages were calibrated using the OxCal v 4.3.2 calibration program (Ramsey Reference Ramsey2017) and the IntCal20 calibration curve (Reimer et al. Reference Reimer, Austin, Bard, Bayliss, Blackwell, Bronk Ramsey and Butzin2020).

RESULTS

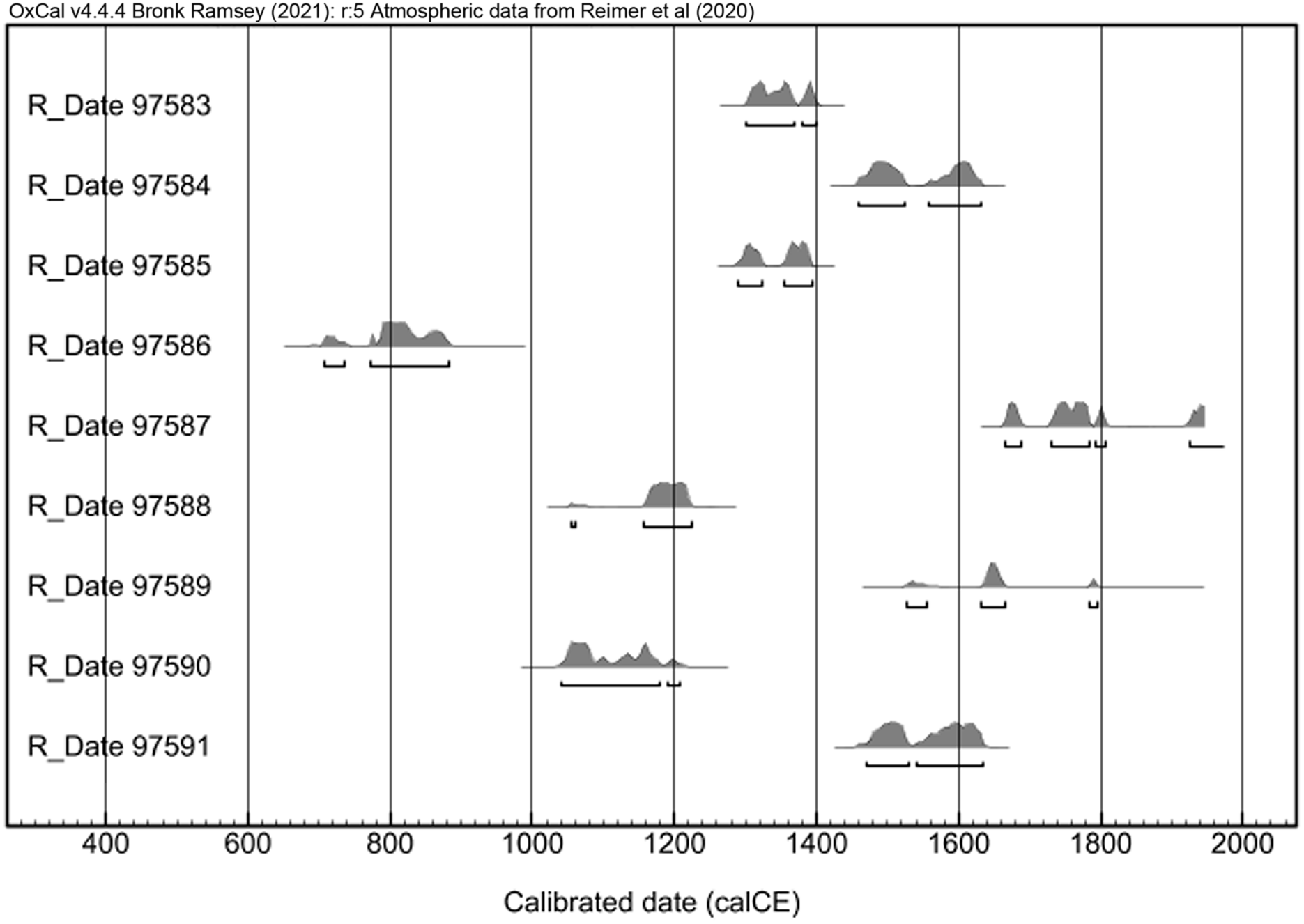

Results of radiocarbon analysis are summarized in Table 1. The measured F14C was used to calculate radiocarbon ages, which were calibrated using IntCal20 calibration curve (Reimer et al. Reference Reimer, Austin, Bard, Bayliss, Blackwell, Bronk Ramsey and Butzin2020) and the OxCal calibration program. The results of calibration are shown in Figure 7 and summarized in Table 1.

Figure 7 Calibrated ages of all the samples.

Table 1 Results of radiocarbon analysis: measured F14C and corresponding 14C age, δ13C measured by AMS on graphite sample, all samples contained ca. 1 mg of carbon. The C/N atomic ratio is based on data from graphitization. The yield shows recovery of material in treatment before graphitization, ** for 2 samples no information is available. Sample Nr. 135 (ETH-97587) was analyzed as not treated (*) and 2 targets of clean sample: X2-Test: df=1 T=1.4 (5% 3.8). Ranges of calibrated ages (95.4%) obtained using IntCal20 calibration curve and OxCal 4.4 online calibration program. Radiocarbon ages of clean sample Nr. 135 (ETH 97587) were combined and calibrated.

DISCUSSION

The radiocarbon calibration curve shows numerous plateaus (Hajdas Reference Hajdas, Turekian and Holland2014; Hajdas et al. Reference Hajdas, Ascough, Garnett, Fallon, Pearson, Quarta, Spalding, Yamaguchi and Yoneda2021), which often are responsible for lower precision of calibrated ages. From the manuscript no. 10950 (Qurʾān; see Figure 1), one sample has been taken (ETH-97586, CC-sample no. 134) and dated to 1223 ± 20 BP. The calibrated age of the parchment is between 706 and 882 CE. One of the intervals, the time period 772–882 CE seems to match with the relative chronology based on its script style, kūfī type D, in the paleographical classification of Déroche (Reference Déroche1983; Reference Déroche1992). This is one of the few known extant leaves of a codex (the whole or part of the Qurʾān) in this script style that has been radiocarbon dated. The result shows that this Qurʾān was produced most probably during the 9th century CE or in the last half of the 8th century CE, however the first half of the 8th century CE cannot be ignored. Three samples of Qurʾān 4319 from the National Museum of Iran have been measured leading to the following results: No.4319 (p. 47): 1299 ± 20 BP, No. 4319 (p. 91): 1283 ± 20 BP and No. 4319 (p. 105): 1273 ± 20 BP (Aghaei and Marx Reference Aghaei and Marx2021:216), as well as two Qurʾāns from the Bavarian State Library, Cod. Arab. 2569 and Cod. Arab. 2817 (Marx and Jocham Reference Marx and Jocham2019:216). The script style of these three fragments can be classified as kūfī type D as well.

A sample taken from pp. 130–133 of manuscript no. 203 (Muǧmal al-Luġah of Ibn Fāris) was tested and the following age of its carbon obtained (ETH 97590, CC-sample no. 138): 915 ± 20 BP, which corresponds to the time span between 1040 and 1206 CE, which is consistent with the date mentioned in the colophon of the manuscript (479 AH/1086 CE; see also Figure 2).

From manuscript no. 5156 (Ḏaḫīrah-ye Kh w ārazmšāhī of Ismāʿīl Ǧorǧānī) two samples (fols. 132 and 65) were taken, of which the radiocarbon has been measured. One could assume that the two folios (fol. 65 and fol. 132) from which the samples were taken were composed at the same time. However, the obtained results of these two fragments differ dramatically: 179 ± 15 BP (ETH-97587, CC-Sample no. 135) and 870 ± 20 BP (ETH-97588, CC-Sample no. 136). These two results correspond to calibrated ages between 1665 and 1950 CE (fol. 132) and between 1054 and 1224 CE (fol. 65), respectively. The radiocarbon age obtained for fol. 65 (ETH-97588) shows that the manuscript was produced before 1224 CE, which is consistent with the date of the colophon: 582 AH/1186 CE (see Figure 3). One could interpret the results obtained on sample ETH-97587 (2 measurements on a clean sample and one on the original, no treatment see Table 1) as an evidence that folio 132 was a later addition to the manuscript. The evidence including different script and language styles in comparison to other folios such as folio 65 confirms the hypothesis that folio 132 has been inserted into the manuscript supposedly to replace an already damaged or lost leaf. There are other folios in the manuscript no. 5156 which show features similar to folio 132 most likely added in a later time to the manuscript. The analysis of samples of these folios could confirm this possibility, a scientific analysis of ink components from the analyzed pages would provide additional data.

Three samples have been taken from the manuscript of Panǧ Ganǧ by Neẓāmī Ganǧawī (CLUT #5179), from three folios 62, 63, and 64 (ETH-97583 = No. 131, ETH-97584 = CC-Sample no. 132, ETH-97585 = CC-Sample no. 133). Samples ETH 97583 and ETH 97585 are to be dated between 1302 and 1400 CE, and between 1289 and 1394 CE, respectively. These results correspond to the date mentioned in the colophon, i.e., the year 718 AH/1318 CE (see Figure 4). However, the calibrated age of ETH-97584 ranges between 1458 and 1631 CE is not consistent with those of the other two samples (ETH 97583 and ETH 97585). This could imply that this folio was a later addition to the original manuscript for which we do not have enough evidence at the moment. To clarify the situation additional samples from this folio as well as other folios of this manuscript should be analyzed. Scientific analysis of ink components of the abovementioned pages would provide additional evidence.

The calibrated age of a sample taken from the manuscript no. 2165 (Ādāb al-Falāsifah attributed to Ḥunayn b. Isḥāq) taken from fol. 15–16 (ETH-97589, no. 137) spans three intervals: 1526–1555 CE, 1632–1666 CE, and 1783–1796 CE. Although affected by the extensive age plateau (Hajdas et al. Reference Hajdas, Ascough, Garnett, Fallon, Pearson, Quarta, Spalding, Yamaguchi and Yoneda2021), this dating precludes the possibility that this manuscript was produced before 1500 CE. In the light of radiocarbon analysis, the claims that the manuscript had been written by the famous scholar Ḥunayn b. Isḥāq cannot be taken as face value (cf. Figures 5a and 5b). The result of radiocarbon dating is also consistent with other information we get from the manuscript: its title page has Shaykh al-Bahāʾī’s (953–1030 AH/1547–1621 CE) stamp (see Dānešpajūh Reference Dānešpajūh1961:858). The result of the radiocarbon dating concurs the fact that the manuscript Ādāb al-Falāsifah was produced during the lifetime of al-Bahāʾī. The result is very interesting since the manuscript belongs to a small number of documents written in a script similar to the Qurʾānic kūfī (cf. Dānešpajūh Reference Dānešpajūh1961:858) containing a text other than the Qurʾān.

Manuscript no. 11263, a large paper codex with texts of the Avesta, was tested by radiocarbon dating of a sample taken from fol. 59 (ETH-97591, CC-Sample no. 139), which resulted in an age between 1471 and 1635 CE. Thus, the age of the paper used for this manuscript is compatible with the date stated in the Pahlavi memoirs in the manuscript and Persian colophons of Wīdēwdād (see also Figures 6a and 6b).

CONCLUSIONS

Occasionally, the age plateaus observed throughout the radiocarbon time range prevent the use of radiocarbon dating as a precise chronometer, which may suggest that radiocarbon dating of historical documents might appear as less beneficial in manuscript studies. Analysis of eight samples of paper and one parchment selected from six manuscripts kept in CLUT, however, illustrates the method’s potential to be applied in studies of ancient manuscripts on parchment or on paper. In the case of seven folios the agreement with philological dating (including paleography) is impressive. The carbon dating of two of the samples resulted in later dates than the manuscripts’ colophons suggested: The dating result of one leaf (ETH 97584) of CLUT #5179 (Panǧ Ganǧ), is much later than the two others carbon measurements (ETH 97583 and ETH 97585), a result which remains unexplained for the moment. In the case of CLUT #5156 (Ḏaḫīrah-ye Kh wārazmšāhī), the colophon’s date is compatible with one of the obtained measurements (ETH 97588), though one leaf of which a sample was taken has a much younger age (ETH 97587), according to radiocarbon dating. The text of this younger leaf exhibits features of Persian language of a later period, thereby creating a relationship of mutual agreement between the dating results and the linguistic analysis. Among the analyzed manuscripts of CLUT, one manuscript (Ādāb al-Falāsifah, no. 2165) had a colophon which was considered by several scholars in the past as probably unauthentic (i.e., the colophon was regarded as an intentional forgery). Carbon dating results prove that all these concerns were justified, because the manuscript’s writing surface was produced more than 700 years after Ḥunayn ibn Isḥāq’s death (873 CE).

What is crucial is the introduction of a scientific method independent from philology and paleography for determining a manuscript’s age. The case of CLUT #5156 (Ḏaḫīrah-ye Kh wārazmšāhī) is a perfect example where evidence from philology and sciences come to the same conclusion, beneficial for the historical understanding of cultural heritage.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Without the generous funding of BMBF (project “Irankoran”) and the support of “Corpus Coranicum” of the Berlin-Brandenburg Academy of Sciences this project could not have been carried out. We would like to thank Tobias J. Jocham (Berlin) for his advice in this campaign. Our thanks are due to the laboratory staff and colleagues at the AMS facility for their support of the described measuring campaign. Our special thanks go to the Central Library of the University of Tehran for cooperation and support. We are indebted to Johanna Schubert (Berlin) for her help with the finalization of this article and to Omar Abdel-Ghaffar (Harvard) for editing of the English text.