1. Introduction

Exposure to language input plays a crucial role in language acquisition, and it has been shown that greater amounts of exposure through activities such as watching TV, listening to music, and playing games results in higher second language (L2) proficiency – affecting both L2 listening and reading comprehension (Lindgren & Muñoz, Reference Lindgren and Muñoz2013). Audiovisual input, in the form of movies and TV series in the original version, has been shown to be a valuable resource for L2 development for both in-class and out-of-class exposure in different parts of the world (see Montero Perez, Reference Montero Perez2022). Moreover, it has been suggested that an extensive viewing approach, in which learners are continuously exposed to large amounts of input over time, could fulfil the need for exposure to ample amounts of L2 input (Webb, Reference Webb, Nunan and Richards2014). For several decades, researchers have also been exploring whether on-screen text can support this learning. Different on-screen modes may include subtitles (translation of the L2 audio track into the first language [L1]), captions (the on-screen L2 text representation of the L2 audio track), textually enhanced (TE) captions (captions with highlighted or underlined target items), and no captions. For instance, it has been found that subtitles support comprehension (Pujadas & Muñoz, Reference Pujadas and Muñoz2020) and that captions and TE captions facilitate learning of vocabulary (e.g. Montero Perez, Peters & Desmet, Reference Montero Perez, Peters and Desmet2014) and grammar (Lee & Révész, Reference Lee and Révész2020; Pattemore & Muñoz, Reference Pattemore and Muñoz2022).

Another area of inquiry has been whether learners’ proficiency level can affect learning from audiovisual input. It has been found that higher-level proficiency viewers demonstrate greater uptake of vocabulary than their lower proficiency peers (e.g. Suárez & Gesa, Reference Suárez and Gesa2019). While the results of audiovisual input studies attest to a significant effect of both on-screen text and proficiency on learning gains, there is little research on whether these factors affect viewers’ feeling of learning, a variable that can shape the learning outcome (Ellis, Reference Ellis2008). In addition, several studies have examined language learners’ relative frequency of exposure to different modes of audiovisual input (i.e. with L1 subtitles, with L2 captions, without on-screen text; cf. Muñoz & Cadierno, Reference Muñoz and Cadierno2021), but there is a lack of research exploring whether L2 viewers switch from one type of viewing to another and what factors might affect any such changes.

This study explores L2 English viewers’ perceptions of learning from audiovisual input with respect to on-screen text and proficiency factors. We also look at changes in preferred viewing mode over time, again with respect to learner proficiency and experience in a pedagogical intervention.

2. Literature review

2.1 Feeling of learning from audiovisual input

While previous research has shown the benefits of audiovisual input, and especially captioned videos (Montero Perez, Van Den Noortgate & Desmet, Reference Montero Perez, Van Den Noortgate and Desmet2013), learners’ perceptions of the effectiveness of L2 audiovisual materials and captioning is also relevant, due to the possible effect these perceptions have on learning. Students’ L2 learning beliefs represent an individual difference variable that influences both the process and outcome of language learning (Barcelos & Kalaja, Reference Barcelos and Kalaja2011; Ellis, Reference Ellis2008). In this study, learning beliefs are operationalized as students’ judgements of what language features they had learned after a period of extensive exposure to L2 audiovisual input.

Audiovisual input studies discussing perceptions of learning from videos can be divided into two types: (a) research exploring overall feeling of learning from out-of-school exposure to audiovisual input (Dizon, Reference Dizon2021; Kusyk & Sockett, Reference Kusyk and Sockett2012) and (b) intervention studies that include an exit questionnaire on feeling of learning after viewing (Montero Perez et al., Reference Montero Perez, Peters and Desmet2014; Sydorenko, Reference Sydorenko2010; Winke, Gass & Sydorenko, Reference Winke, Gass and Sydorenko2010). Regarding the first category, out-of-school exposure questionnaire studies have found that language learners find target language audiovisual materials useful for their language development, especially for listening skills (Dizon, Reference Dizon2021) and vocabulary and expressions (Kusyk & Sockett, Reference Kusyk and Sockett2012). The second type of research, viewing intervention studies, report that participants perceive videos as being helpful for comprehension (Rodgers & Webb, Reference Rodgers and Webb2017), vocabulary and expressions (Stewart & Pertusa, Reference Stewart and Pertusa2004), and speech segmentation (Winke et al., Reference Winke, Gass and Sydorenko2010). However, learners may not always be aware that learning is taking place, as was found in Sydorenko’s (Reference Sydorenko2010) study where the participants were asked whether they learned any L2 Russian vocabulary from viewing three 2–3-minute video clips. Many participants did not perceive any vocabulary learning from the treatment, although significant vocabulary gains were in fact recorded. The author suggested that the lack of feedback might have affected perceptions of learning and caused this incongruous result.

However, most studies focusing on learners’ beliefs and attitudes towards audiovisual input include only a single viewing and have not looked at perceptions of learning from extensive exposure. This is an important limitation, given that Rodgers (Reference Rodgers2013) showed that pre-intermediate and intermediate participants’ positive beliefs about content comprehension, listening ability, and vocabulary learning from videos increase over time as participants watch more episodes and become familiar with the TV series.

Rodgers (Reference Rodgers2013) provided valuable insights on attitudes and the change of perceptions over time, but did not include different captioning modes. The presence or absence of captions, subtitles, or other forms of on-screen text that students experience during the viewing is likely to play an important role in feeling of learning. Pujadas (Reference Pujadas2019) addressed this issue and compared the perceived usefulness of extensive exposure to TV series in two groups of secondary school learners who viewed the episodes with either L1 Spanish subtitles or L2 English captions. The results indicated that the L2 captions group had a significantly higher feeling of learning than the L1 subtitles group for vocabulary retention.

In another longitudinal study, Mariotti (Reference Mariotti, Gambier, Caimi and Mariotti2014) focused on the perceived usefulness of audiovisual materials for language learning from several European countries and involved extensive exposure to audiovisual input. The participants were asked to complete pre- and post-exposure questionnaires and watch subtitled audiovisual materials with the audio in one of several European target languages at least once a fortnight over a nine-month period. Most participants reported an improvement in their listening skills, and almost 70% reported an intention to continue viewing subtitled materials. Unfortunately, the study did not distinguish between different types of on-screen text (i.e. L1 subtitles and L2 captions), making it impossible to tease apart feeling of learning in each mode.

Taking together studies investigating both single viewings and extensive exposure to audiovisual input, it seems that learners are aware of learning taking place to some extent, and that awareness increases with length of exposure to audiovisual materials. However, none of these studies addressed proficiency differences, a factor that could be essential in the feeling of learning from audiovisual input (Teng, Reference Teng2021: 37). In addition, the studies mostly focused on vocabulary and comprehension, and did not compare the feeling of learning of various aspects of language, such as vocabulary, expressions, grammar, and pronunciation. Although a few studies have provided evidence for the benefits of captioned over uncaptioned input for language gains (see Montero Perez, Reference Montero Perez2022, for a review), a comparison of feeling of learning from different captioning modes is warranted. Importantly, to our knowledge, no prior research examined feeling of learning from TE captions, making this a particularly interesting aspect to consider.

For these reasons, it is important to find out whether learners perceive learning from various audiovisual input modes differently (i.e. L1 subtitles, L2 captions, TE captions, and no textual support). A study designed to investigate input modes would also allow triangulation with the language gains observed in different studies with various types of on-screen text. In addition to investigating to what extent students believe they are learning from audiovisual input, it is also important to consider students’ attitudes towards viewing such materials, particularly when combined with on-screen text. The next section discusses the importance of viewing preferences and how those are correlated with language learning from audiovisual input.

2.2 Viewing preferences and attitudes towards on-screen text modes

Modes of viewing perceived more positively by learners are more likely to hold their interest and therefore enable greater amounts of language input. Similar to feeling of learning, viewing preferences have been investigated through two different approaches, as noted above: non-intervention questionnaire studies, and intervention studies with an exit survey. Several questionnaire studies that aimed to grasp participants’ viewing habits (Dizon, Reference Dizon2021; Kusyk & Sockett, Reference Kusyk and Sockett2012; Muñoz, Reference Muñoz2020) reported a wide variety in terms of on-screen text preferences and perceptions of usefulness of different captioning modes. For example, a comparison of Spanish and Danish teenagers’ out-of-school exposure revealed that national language viewing policies (i.e. dubbed or subtitled cultures) affected frequency of viewing dubbed and target language material (Muñoz & Cadierno, Reference Muñoz and Cadierno2021).

Other studies inquired about participants’ viewing preferences after viewing interventions. For instance, intermediate-level French learners reported a preference for captions over no captions after viewing three clips of 16 minutes in total (Montero Perez et al., Reference Montero Perez, Peters and Desmet2014). As for the preference for L1 subtitles over L2 captions, the intermediate-level participants in the study by Stewart and Pertusa (Reference Stewart and Pertusa2004), who watched two full-length Spanish films with L2 Spanish captions or L1 English subtitles, had different attitudes towards two types of on-screen text. The participants who watched the films with L2 captions, whose vocabulary gains were slightly higher, reported a perception of vocabulary learning and a clear preference for this type of input. Similarly, those who received the audiovisual input with L1 subtitles suggested that they could have benefited more had they viewed the films with L2 captions instead. The L2 captions group also reported their intent to continue watching with L2 captions outside of the classroom for learning purposes.

Despite the overall positive attitude towards L2 captions, there is no consensus among language learners about the usefulness of captioning. For instance, Winke and colleagues (Reference Winke, Gass and Sydorenko2010) asked their participants about their reactions towards watching three short (3–5 minutes) videos with or without captions. The learners perceived captions as a useful tool to chunk the speech sequence and as a helpful scaffold, though a few students were concerned about captions being more of a crutch and distraction that prevented them from focusing on the action and the soundtrack. Similarly, in Teng (Reference Teng2021) some participants shared their concerns about the use of captioned video and suggested that the main issues were proficiency related; that is, due to having to split their attention between text and audio, they found that their proficiency level was not high enough to process both input channels simultaneously. Another disadvantage of viewing videos with captions mentioned by these participants was a worry about over-reliance on on-screen text, which they thought would never fade, supporting the previous suggestion in Winke et al. (Reference Winke, Gass and Sydorenko2010) that captions may be perceived as “crutches”.

Viewing preferences may also be affected by age and proficiency. Two studies based in different European regions (De Wilde, Brysbaert & Eyckmans, Reference De Wilde, Brysbaert and Eyckmans2021, in Flanders; Muñoz & Cadierno, Reference Muñoz and Cadierno2021, in Spain and Denmark) found that viewing with L1 subtitles was associated with low L2 knowledge; that is, participants with lower English proficiency tended to opt for L1 subtitles, while their more proficient peers preferred purely English input. It seems that older learners, with higher language proficiency, and/or more experienced viewers, might opt for L2 captions instead of L1 subtitles (Muñoz, Reference Muñoz2020).

Difficulties lower proficiency learners might face while viewing captioned audiovisual input have also been documented. Teng’s (Reference Teng2021) participants felt their low proficiency reduced the value of audiovisual materials as a source of input due to the difficulty of focusing on multiple input channels. Another example is Taylor’s study (Reference Taylor2005), where captions were considered distracting for lower proficiency level students who watched a 10-minute video in Spanish. In a recent study, De Riso (Reference De Riso2021) found that 15-year-old Italian adolescents preferred watching original version English media with L1 subtitles, while their 17-year-old peers seemed to switch to L2 English captions. Similarly, in Pujadas (Reference Pujadas2019), adolescent learners reported a shift in viewing preference before and after an extensive viewing intervention. The participants’ preference for L1 subtitles decreased by 40%, and preference for L2 captions increased by 34.5%. At the same time, there was a small increase of 10% in students viewing without any on-screen text. Interestingly, the participants in the captions group reported their intention to continue viewing with L2 captions instead of L1 subtitles, in spite of a perception that L2 captions were more demanding for them. This viewing intervention therefore allowed the young participants to see a clear advantage in viewing without any L1 support. In terms of proficiency differences, the lower-level students (A1) reported a higher reliance on on-screen text, while the participants of A2/B1 level considered on-screen text to be distracting. Overall, the self-reported data in Pujadas (Reference Pujadas2019) showed a shift from L1 subtitles towards L2 captions over time, especially for the more proficient participants and those who watched with L2 captions during the intervention.

While a number of studies have explored the viewing preferences and attitudes towards on-screen text, there is very little research exploring changes in viewing habits of the same viewers (e.g. Pujadas, Reference Pujadas2019). Mariotti (Reference Mariotti, Gambier, Caimi and Mariotti2014) suggested that regular exposure to audiovisual materials (once a fortnight for nine months) allows participants to develop the habit of viewing audiovisual materials with L1 subtitles. The questionnaire data also indicated that L1 subtitles were associated with viewing for leisure, while learners who were motivated for language learning preferred L2 captions. In other studies, it was also found that choosing one type of on-screen support over another might depend on students’ confidence and familiarity with different viewing modes. For example, Vanderplank’s (Reference Vanderplank2019) participants reported less use of captions as they became more familiar with the input. This finding is in line with the study by Rodgers and Webb (Reference Rodgers and Webb2017), where the more familiar the participants became with the TV series, the more confident they felt about viewing without captions.

The foregoing review of the literature has shown than several previous studies have investigated learners’ feeling of learning and viewing preferences through post-viewing questionnaires or interviews. However, many of these studies are based on qualitative data, often from small populations and offering only descriptive analysis. This leads to conclusions that might not be generalizable; inferential statistics would be needed to draw stronger conclusions. Moreover, to our knowledge, there has been only one study that documented a change of viewing preferences over time (Pujadas, Reference Pujadas2019).

The present study extends the area of audiovisual input research by investigating the feeling of learning from different captioning modes by students with varying proficiency levels. It also contributes to the small body of research in the area of changes in viewing preferences and explores those changes over an extensive intervention.

The aim of the present study is threefold: to explore L2 English undergraduate students’ feeling of learning from extensive exposure to full-version TV series, to investigate the role of proficiency and intervention captioning mode (with captions, without captions, and with enhanced captions) on that feeling of learning, and to identify any preference change in their use of captioning mode outside of the classroom in relation to students’ proficiency and in-class viewing mode.

The following research questions are addressed:

-

1. To what extent is students’ feeling of learning from audiovisual input affected by intervention viewing mode and proficiency?

-

2. To what extent do students’ viewing preferences change over time, and are any changes related to proficiency and/or intervention viewing mode?

3. Methodology

3.1 Participants

The study involved four intact classes (groups) of oral and written communication in English including 175 Catalan/Spanish bilingual students pursuing undergraduate degrees in audiovisual communication. Students who did not watch all the episodes (see below) or complete all the required questionnaires (n = 39) were excluded, leaving 136 participants. The participants’ ages varied from 17 to 32 years old (M = 19), and their proficiency was from A1 to C2, with a mean of B2, according to the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (CEFR) levels (Council of Europe, 2001). This language course is unstreamed and always includes students with a variety of proficiency profiles. The four classes were randomly assigned to three different viewing conditions: two classes viewed with L2 captions (n = 71), one with TE captions (n = 38), and one without captions (n = 27).Footnote 1

3.2 Audiovisual input

Ten full-length episodes (about 22 minutes each for a total of 227 minutes) of the first season of the fantasy comedy TV series The Good Place (Schur, Reference Schur2016) were shown to the participants twice a week in their original order of appearance. The plot follows Eleanor, who dies and is sent to “the Good Place”, meant for exceptional individuals who dedicated their lives to helping others. However, she realises that she does not belong there and tries to become a better person to stay in the Good Place. This authentic audiovisual material was chosen because it had not been broadcast on Spanish central TV and, consequently, the participants were unlikely to have watched it before the study. In addition, it contained appropriate language for the classroom setting (e.g. no cursing, no violent scenes).

3.3 Research setting

The participants attended compulsory English classes and were taught by the same teacher twice a week for a total of three hours per week. The course followed an English for Specific Purposes approach; it was vocabulary based and related to students’ majors on audiovisual communication (advertising, cinema, or marketing). The viewing intervention was integrated as one of the classroom activities focusing on the comedy genre in terms of audiovisual communication, humour, and screenplay writing. Before viewing each episode, students were pre-taught cultural content. At the end of each episode, the participants were asked to complete multiple-choice comprehension questions. The intervention part of the course was about 45 minutes per session. The participants received 10% of the final grade for completing learning activities related to the TV series.

3.4 Instruments

Participant proficiency was measured using the Oxford Placement Test (OPT) (Allan, Reference Allan2004). This proficiency test consists of two parts: Listening and Grammar.

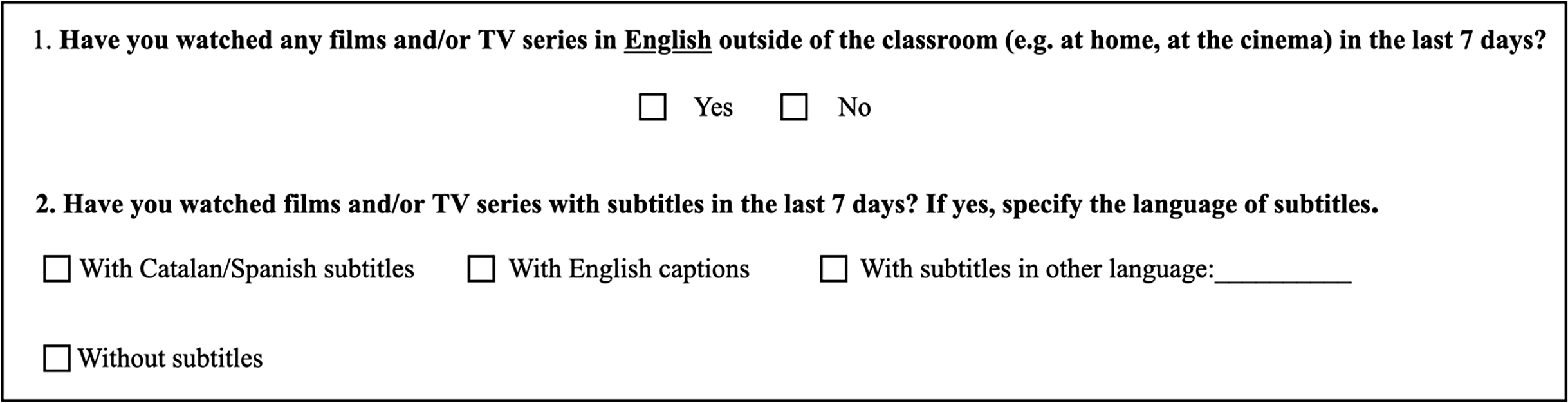

The pre-viewing questionnaire on exposure to L2 audiovisual input contained nine questions on students’ exposure to English media and viewing preferences (Supplementary Material A). The answers to three of these questions were analysed to address the study’s research questions (see Figures 1 and 2). The post-viewing questionnaire had the same format as the pre-viewing questionnaire, with checkboxes that allowed for multiple answers, but also included two questions about participants’ feeling of learning from The Good Place TV series.

Figure 1. Questions on exposure to L2 original version audiovisual input, pre-viewing and post-viewing questionnaire

Figure 2. Post-viewing questionnaire

Finally, at the end of the course, the participants were asked to write an essay with their reflections on the contents of the course and their progress (see Supplementary Material B for the questions that students were asked to address). As many students chose to elaborate on their experience with the TV series intervention during this task, these reflections were considered to triangulate the quantitative findings.

All the research instruments were created in English, as this is the language of instruction.

3.5 Procedure

One week before the intervention, the participants completed the proficiency test and the pre-viewing questionnaire. One week later, all participants viewed two episodes on two separate days and completed comprehension questions to ensure they were following the content of the TV series and were focused on viewing. The 10 episodes chosen for the study were watched in five consecutive weeks. On the last day, after viewing episode 10, the participants completed a post-viewing questionnaire about their feeling of learning from the TV series and their exposure to the original version videos outside of the classroom. The pre-viewing and post-viewing questionnaires were administered six weeks apart. In order to avoid influence on questionnaire responses, students’ attention was not drawn to particular language features (e.g. vocabulary, grammar, pronunciation). At the end of the course, the students submitted a written reflection on the content of the course where one of the topics they commented on was their experience with the viewing of the TV series in the classroom, as seen above.

3.6 Scoring and data analyses

This section focuses on how the research instruments’ scores were processed and prepared for the data analyses. The quantitative data were analysed using SPSS, the participants’ reflections essays were analysed manually, and participants’ references to viewing were used for data triangulation.

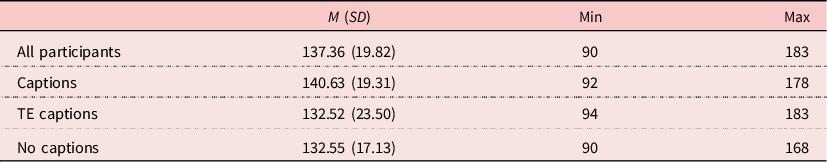

First, proficiency levels were coded as three groups: learners with a score between 90 and 119 were operationalized as A1-A2 elementary group, those with between 120 and 149 assigned to the B1-B2 intermediate group, and those with the scores higher than 150 were assigned to the C1-C2 advanced group, based on the OPT instruction manual. The descriptive statistics for proficiency scores are presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Participants’ proficiency scores per experimental group (OPT)

Note. OPT = Oxford Placement Test; TE = textually enhanced.

Language features were operationalized as vocabulary, expressions, grammar, pronunciation, and no feeling of learning. The students did not raise any language-related features in the “yes, other” option of the questionnaire, so it was not included in the analysis. Finally, the use of captions was operationalized as “with L2 captions”, “with L1 subtitles”, and “without captions”.

The preliminary analysis showed that there was no significant difference between the intervention groups’ proficiency levels, F(2, 133) = 2.242, p = .110, nor their exposure to audiovisual input outside of the classroom before, F(2,133) = .428, p = .653, or after, F(2, 133) = 2.218, p = .113, the intervention. Therefore, the intervention groups in this study were comparable.

4. Results

4.1 Research question 1: Feeling of learning

This question aimed to explore students’ feeling of learning and whether it was affected by viewing mode and student proficiency. To answer the question, a series of binomial linear models for repeated measures were fitted in SPSS software. The model included feeling of learning (yes, no) as a dependent variable, and type of language feature (vocabulary, expressions, grammar, pronunciation, and no feeling of learning), intervention viewing group (with captions, without captions, with enhanced captions), and proficiency group (A1-A2, B1-B2, C1-C2) as independent variables. The model also included two interactions between intervention viewing mode and language feature, and proficiency group and language feature. The intervention viewing mode was not a significant factor, F(2, 663) = .597, p = .551, and neither was the interaction between the intervention viewing mode and language feature, F(8, 655) = 1.424, p = .183; therefore, they were not included in the final model.

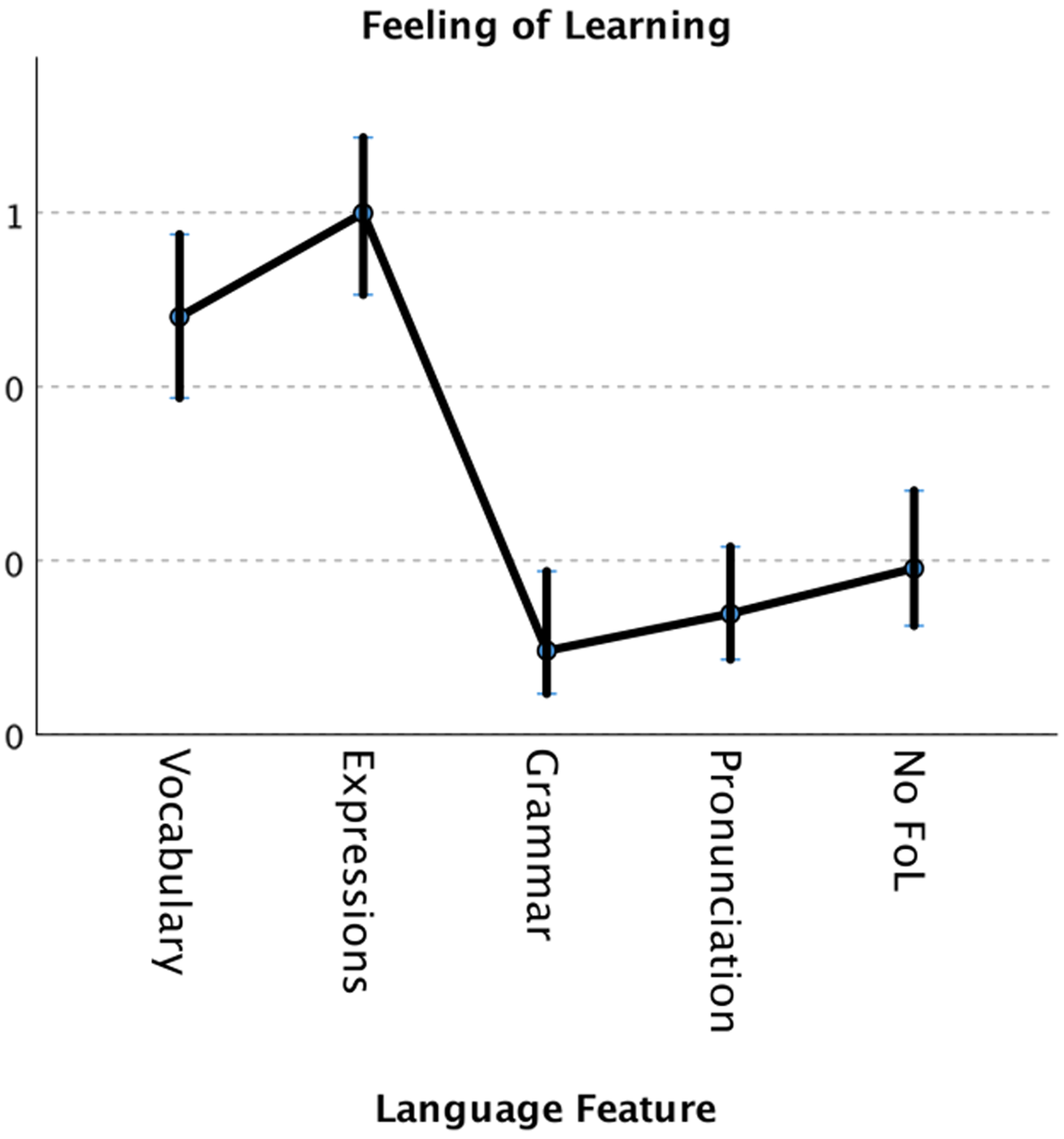

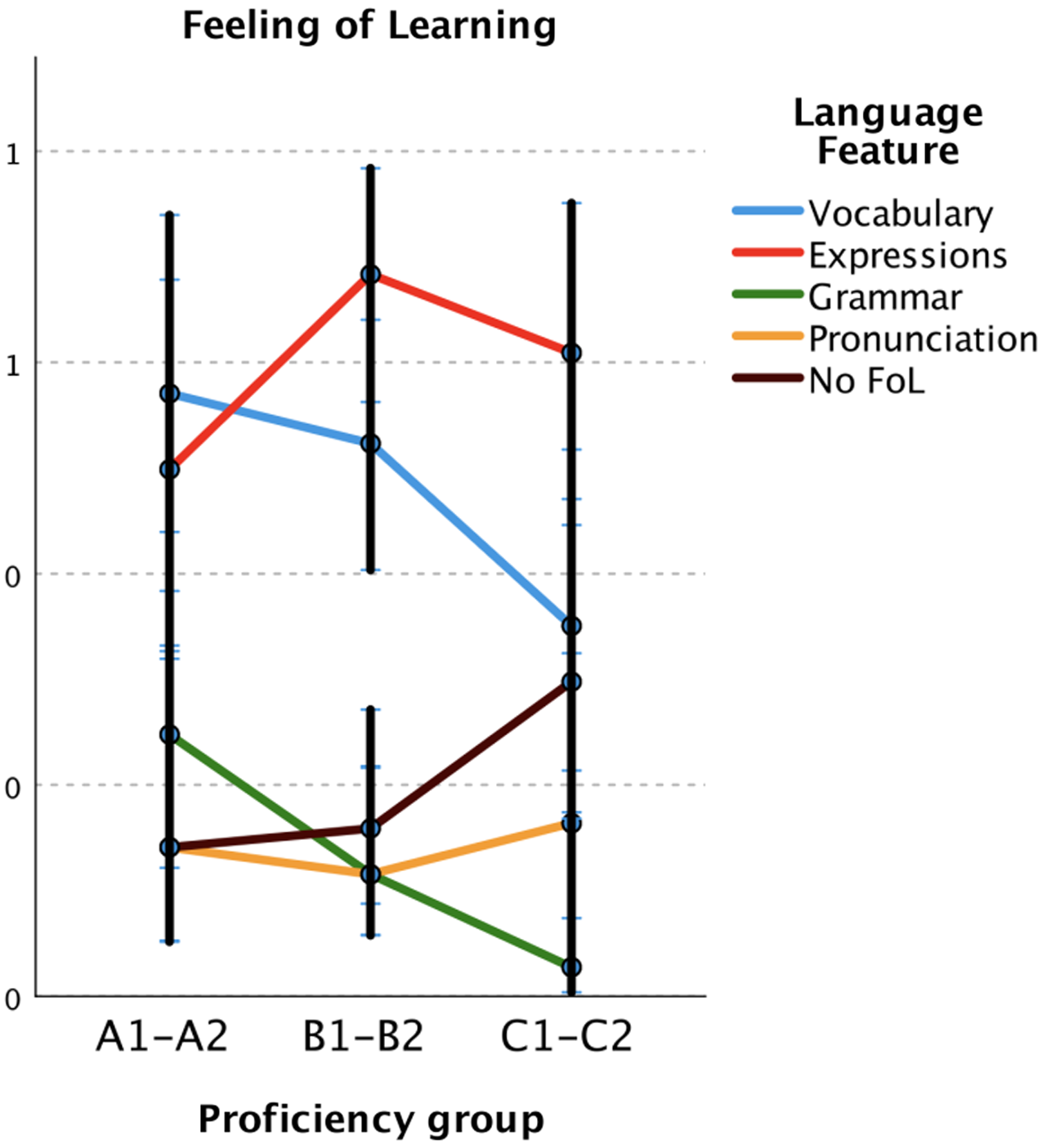

The final model yielded a significant effect of language feature, F(4, 665) = 21.235, p < .001, but not a significant effect of proficiency group, F(2, 665) = .979, p = .376. However, there was a significant interaction between proficiency group and language feature, F(8, 665) = 2.008, p = .043, on feeling of learning, suggesting that proficiency group itself could not explain students’ feeling of learning.

Regarding the first significant factor, language feature, it can be seen in Figure 3 and Table 2 that vocabulary and expressions were perceived to be learnt the most, followed by no feeling of learning, pronunciation, and grammar. The post hoc Bonferroni pairwise contrastFootnote 2 revealed that there was no significant difference between the feeling of learning of vocabulary and expressions, t(665) = 1.804, p = .258. The analysis showed that there was a greater perception of learning of vocabulary (V) and expressions (E) than grammar, V: t(665) = 6.501, p < .001, E: t(665) = 8.758, p < .001; pronunciation, V: t(665) = 5.905, p < .001, E: t(665) = 8.201, p < .001; and no feeling of learning, V: t(665) = 4.726, p < .001, E: t(665) = 6.851, p < .001. There was no significant difference in learning perception between pronunciation and grammar, t(665) = .907, p = .589, and there was no significant difference between no feeling of learning and pronunciation, t(665) = 1.049, p = .589, or grammar, t(665) = 1.852, p = .258.

Figure 3. Estimates of feeling of learning (FoL) for all participants

Table 2. Estimated means of feeling of learning by language feature

Note. CI = confidence interval.

To summarize this pairwise comparison, vocabulary and expressions were considered to be learnt the most, there was no difference between the feeling of learning of grammar and pronunciation, and participants were more likely to report vocabulary or expressions learning than no learning at all.

Concerning the proficiency group and language feature interaction (see Figure 4 and Supplementary Material C), the comparison between proficiency groups revealed that the elementary (A1-A2) group was more likely to report perceived learning of grammar than the advanced group, t(665) = 2.590, p = .029. Interestingly, the advanced group tended to report no feeling of learning significantly more than grammar learning, t(665) = 3.320, p = .007. There was no significant difference between the rest of the groups and language feature comparisons.

Figure 4. Estimates of feeling of learning (FoL) per proficiency group

The second question of the post-viewing questionnaire asked participants to give an example for each of the categories in which they had affirmed a feeling of learning. Many participants did not provide examples, or only provided examples for some categories. Those who responded mainly reported individual words and expressions (e.g. soulmate, to move on). Six students gave examples of grammar learning, five in terms of improving their “sentence order”, and another reported that they had improved verb tenses. Those who responded to have learned pronunciation mostly wrote that they had learnt the difference between the American and British accents (one of the TV series characters had a British accent). A qualitative analysis of students’ reflections was also performed to triangulate the abovementioned results. The analysis suggested that higher-level proficiency students were concerned about the effectiveness of viewing TV series for language learning and suggested that some focus on form should take place as well if they want to improve their skills:

The learning process is not about watching something and hoping that will make you learn a foreign language, it is about searching and translating the words or expressions you don’t know. (ID035, captions, B1-B2)

On the other hand, their peers from the elementary proficiency group were less critical and shared their positive beliefs about learning from audiovisual input:

I didn’t trust watching series in English would help me learn the language. Now I think it is one of the fastest and funniest ways to learn a language. (ID018, captions, A1-A2)

To summarise the results of the proficiency group and language feature interaction, there was no difference between feeling of learning of vocabulary and expressions for all three proficiency groups, suggesting that vocabulary and expressions were considered to be learnt the most regardless of proficiency level. The elementary group felt that they were learning grammar more than the advanced group. Also, there was a tendency for higher proficiency participants to have weaker feeling of grammar learning (see Figure 4). The advanced group had a tendency towards reporting no feeling of learning at all. Likewise, the qualitative results of students’ reflections suggest that elementary group participants were more likely to be positive about learning from the intervention, while higher proficiency students appeared to be more dubious.

4.2 Research question 2: Viewing preferences

The second research question explored captioning mode preferences outside the classroom and whether these preferences changed during the in-class viewing intervention. We were also interested in whether the changes were affected by participants’ in-class viewing modes and their proficiency levels. To answer this question, a series of McNemar nominal paired samples analyses were run. This test was chosen because it allows analysis of the changes in dichotomous variables at two different points in time (Field, Reference Field2018).

The answers to the survey question that asked participants if they watched media in English in the last week were analysed. If the participants chose a yes option, they then had to choose the mode in which they watched the original version media (with L1 subtitles, with L2 captions, without subtitles or captions). The answers to the same question at the beginning and at the end of the intervention were compared. The participants’ viewing in the L2 did not change: the percentage of students watching in the target language was 81% at the beginning and 82.5% at the end of the intervention.

First, the analysis was run with the answers from all the participants who reported watching English media in the last seven days, regardless of the intervention viewing mode or proficiency group. The proportions of viewing preferences are presented in Supplementary Material D. The habit of viewing with L1 subtitles did not change, χ 2(1) = 2.857, p = .091. The proportion of L2 captions users decreased at the end of the intervention, χ²(1) = 66.329, p < .001. Finally, the proportion of viewers without captions or subtitles significantly increased, χ²(1) = 21.729, p < .001.

To see whether these changes were affected by either the intervention viewing mode or participants’ proficiency levels, the McNemar tests were run again. First, the effects of intervention viewing mode were considered. In the L2 caption group, the proportion of students who watched with L1 subtitles did not change, χ²(1) = .762, p = .383, while watching with L2 captions significantly decreased, χ²(1) = 35.220, p < .001. The proportion of viewers watching without captions significantly increased, χ²(1) = 10.618, p = .001.

As for the TE captions group, there was a tendency to watch less with L1 subtitles, χ²(1) = 3.200, p = .063, a significant decrease in watching with L2 captions, χ²(1) = 19.048, p < .001, and a significant increase in watching without captions, χ²(1) = 11.250, p < .001. Finally, the no captions group did not change their preference regarding viewing with L1 subtitles, χ²(1) = .000, p > .05. Watching with L2 captions significantly decreased, χ²(1) = 8.643, p = .002, and the proportion of students viewing without captions did not change significantly, χ²(1) = .563, p = .454.

The last series of McNemar tests explored whether these changes in viewing preferences were affected by students’ proficiency levels. For the elementary group, there was no significant difference in the proportion of L1 subtitles users (p = .375), but the intervention led to more participants watching significantly less with L2 captions, χ²(1) = 11.077, p < .001. There was an insignificant increase in viewing without captions (p = .508). Similarly, the intermediate group did not change their L1 subtitles viewing frequency (p = .210), and watched significantly less with L2 captions, χ²(1) = 32.237, p < .001. The proportion of viewers without captions significantly increased, χ²(1) = 21.441, p < .001.

As for the advanced group, similar to the rest of the groups, there was no significant difference in viewing with L1 subtitles (p = .791), and there was a significant drop in viewing with L2 captions, χ²(1) = 19.360, p < .001. The proportion of viewing without captions did not change significantly (p = .124), but there was a tendency to watch more without captions.

These quantitative results are supported by students’ end-of-the-course reflections on their experience with the viewing intervention. Some lower-level students reported that they stopped viewing dubbed versions:

Watching The Good Place changed my habits of watching series in the language that has been filmed. However, I don’t watch it with captions, but with subtitles in Spanish. (ID125, enhanced captions, A1-A2)

Other elementary-level students suggested that first they need to watch the episodes with L1 subtitles and then gradually switch to L2 captions:

After this experience, I think I have to watch more TV series and films in English with subtitles in Spanish and later with English captions to learn more new expressions. (ID016, captions, A1-A2)

Interestingly, although there was a significant drop in viewing with L2 captions, several students from the captions group highlighted their intent to continue viewing with L2 captions:

I almost never watch anything with captions because I thought that I would not understand. As I saw that I can understand most of The Good Place, I started watching TV shows with captions. (ID134, enhanced captions, A1-A2)

A few advanced-level students reported being distracted by captions before the start of the intervention:

I prefer to see the movies without captions because they used to distract me. I would only use them if the level of the film is too high for me. (ID054, captions, C1-C2)

Finally, the results show that participants in the no captions group opted to continue viewing without captions after the intervention:

Watching The Good Place has changed my learning habits, it gave me confidence to not use subtitles anymore. My listening is getting used to verbatim and I feel very confident about it. (ID068, no captions, C1-C2)

In general, the participants’ habit of watching with L1 subtitles diminished (though the differences were not statistically significant) over the time period of this study, and most of the participants showed a pattern to shift from viewing with L2 captions to without captions. There was no variation between the viewing modes groups, but there was a significant decrease in viewing with L2 captions for all three proficiency groups, and a significant increase in viewing without captions only for the intermediate group.

The qualitative analysis of students’ reflections showed that elementary-level participants realised that they are capable of watching in the target language, but with the L1 support first. The results also tentatively suggest that higher proficiency learners who watched without captions switched to this viewing mode daily.

5. Discussion

This study set out to examine how the participants perceived learning from an audiovisual intervention. It also analysed students’ out-of-school shift in viewing preferences before and after watching 10 episodes of a TV series. The results were analysed considering such factors as participants’ intervention viewing condition (with captions, with enhanced captions, without captions) and proficiency levels.

The first research question explored whether the feeling of learning from the audiovisual input depended on the intervention viewing mode and participants’ proficiency. The results indicated that the intervention viewing mode did not affect feeling of learning. This result is surprising as previous research has suggested that captioned audiovisual input is objectively more beneficial than uncaptioned for various language features (see Montero Perez, Reference Montero Perez2022). However, several studies have shown that actual learning gains and feeling of learning do not always match (e.g. Deslauriers, McCarty, Miller, Callaghan & Kestin, Reference Deslauriers, McCarty, Miller, Callaghan and Kestin2019; Sydorenko, Reference Sydorenko2010). This lack of intervention viewing mode effect confirms that students may not always be aware of their learning progress or the fruitfulness of L2 captions use for their language learning. Indeed, Montero Perez (Reference Montero Perez2022) suggested that learners’ awareness of the benefits of audiovisual input and various on-screen text modes should be raised so that learners could fully engage with the input and benefit from it to a greater extent. Language instructors should take this suggestion and the present study results into account while informing their students about the benefits of various on-screen text modes and audiovisual input.

Regarding language features, vocabulary and expressions were perceived as learnt the most, while pronunciation and grammar, the least. This is in line with previous research reporting perceived learning of vocabulary and expressions (Dizon, Reference Dizon2021). Grammar was considered one of the least learnt features; however, the results of our previous studies with the same participant pool (Pattemore & Muñoz, Reference Pattemore and Muñoz2020, Reference Pattemore and Muñoz2022) suggested that students in all the intervention groups had significant grammar gains, with the captions group outperforming the rest of the participants. One of the explanations of a low feeling of grammar learning in the present study may lie in the unconscious and incidental nature of uptake from audiovisual input (Vanderplank, Reference Vanderplank2016). It is possible that the participants were not aware of learning taking place, especially for such a complex language feature as syntax. Another possible explanation of this contrariety in the results could lie in the lack of feedback (Sydorenko, Reference Sydorenko2010) and no classroom opportunity to produce comprehensible output (Swain, Reference Swain, Gass and Madden1985). Exposure to audiovisual input might be enough to obtain grammar gains (Pattemore & Muñoz, Reference Pattemore and Muñoz2020, Reference Pattemore and Muñoz2022), but a lack of output or explicit instruction could result in a weaker feeling of learning. Finally, the participants’ metalinguistic awareness may have affected their responses, as they may, for example, have had a narrow view of what counts as “grammar”. The responses to the open-ended question indicated that the participants’ understanding of which grammatical structures they encountered was essentially limited to “sentence order”, and may not have included such target syntactic structures as reported speech, passive constructions, and conditionals.

Regarding proficiency, some interesting results were obtained for the elementary (A1-A2) and the advanced (C1-C2) groups. The lower proficiency participants reported a stronger feeling of grammar learning than their more advanced peers. Additionally, the qualitative analysis of students’ reflections revealed that the elementary group was more positive about their overall learning outcomes than the participants with higher proficiency levels. In contrast, the advanced group was more likely to report no feeling of learning than the other groups, and these learners were more sceptical about their progress and the educational value of the TV series. These results could be explained by the rate of learning at different proficiency levels (Knight, Reference Knight2018). The elementary-level students had more room for improvement in terms of relatively simpler words, phrases, and structures available, and consequently a higher feeling of progress. Once a learner reaches the “intermediate plateau”, their progress decelerates, resulting in a weaker sense of progress. Higher proficiency learners might have benefited from explicit feedback and practice to see their progress; otherwise, viewing TV series was solely perceived as a non-educational leisure activity (Vanderplank, Reference Vanderplank2019). Psychological studies suggest there is a danger that students fail to perceive audiovisual materials as a source of language learning when they do not have to expend much mental effort (Salomon, Reference Salomon1984). When learners consider an activity easy or entertaining (i.e. videos), they make less effort to learn from it, consequently resulting in lower learning achievement and perception of learning.

As regards viewing outside of the classroom, no increase in the number of participants who watched in the L2 was observed. This could be explained by the fact that the post-viewing questionnaire was taken in the middle of the busy academic semester, a time when students’ energy may have been consumed by classwork rather than watching TV for pleasure. The second research question identified a shift in preferred viewing mode (i.e. L1 subtitles, L2 captions, no on-screen text) associated with the intervention viewing mode and participants’ proficiency level. The results indicated no substantial change in viewing with L1 subtitles. This change might not have been possible because the participants might not have been able to completely switch from L1 subtitles due to either their lower proficiency, as reported by several elementary-level participants in their course reflections, or external factors, such as family and friends who could not follow the content without L1 on-screen support (Pujadas, Reference Pujadas2019).

The biggest change in the viewing preferences was observed with the L2 captions mode. At the beginning of the intervention, 78% of participants reported viewing with L2 captions, whereas by the end of the intervention, only 11% of students did. The reasons for this significant switch for all intervention groups and proficiency levels may be various. The elementary group might have found that the intervention experience of watching with L2 captions regularly was too challenging. It was suggested by several elementary proficiency participants that while watching videos at home, they had to watch the videos several times to grasp the content, and they still relied on L1 subtitles. As for the more proficient participants, a natural shift from viewing with L2 captions to without captions was observed; the participants might have realised that they did not have to continue relying on captions anymore as they became more confident viewers throughout the intervention.

The extensive viewing nature of the present study allowed us to observe how students, starting from the intermediate proficiency level, go through a captioning phase and move on to uncaptioned input. The reason why all groups opted for viewing less with on-screen support could also lie in their raised confidence in viewing original version audiovisual input (Vanderplank, Reference Vanderplank2019). After a regular exposure to L2 captions, the captioning groups may have realised that they did not need the on-screen support anymore. Similarly, the no captions group had to adjust to viewing without any textual support, resulting in the creation of a habit of viewing more without captions, as reported by several participants. The results of this study do not support previous studies’ concerns about over-reliance on captions (Winke et al., Reference Winke, Gass and Sydorenko2010). Furthermore, only four participants in the captions group expressed distraction or annoyance with captions, but this attitude was apparent before the intervention and therefore was not affected by the classroom viewing.

Lastly, although the analysis did not yield any increase in viewing with L2 captions, or switch from L1 subtitles to L2 captions, several individual responses provide evidence that some students benefited from the captioned intervention and took up a habit of viewing with L2 captions, suggesting that this viewing intervention inspired a few students to move from L1 subtitles to L2 captions.

6. Conclusions

This study presents novel results for the area of learning from audiovisual input. Specifically, it analysed viewers’ feeling of learning from 10 episodes of a TV series, and participants’ change in viewing preferences in a six-week period. The results support previous research indicating that vocabulary and expressions are perceived to be learnt the most from audiovisual input. Surprisingly, we found no difference in feeling of learning of different intervention groups. Although previous research documented that captioned input is more beneficial for content comprehension, vocabulary, and grammar learning (Montero Perez, Reference Montero Perez2022), our participants in the captioning groups (both enhanced and unenhanced) did not report more feeling of learning than the no captions group. More research is needed to uncover the reasons behind this incongruity between actual gains and feeling of learning, but such actions as awareness raising and feedback provision are recommended to make the learning process through audiovisual input more clear and fruitful.

The study is not without limitations. The first lies in the limited data of students’ examples of what they had learnt. Although the questionnaire included this question, it did not elicit a variety of answers. The results may have been clearer had we organised interviews or focus groups after the viewings. Also, the TV series may not have been difficult enough for the advanced learners to feel that they learnt something new.

Importantly, this is the first study to address the variety in feeling of learning from audiovisual input through a proficiency difference perspective. We showed that elementary-level participants are more likely to perceive language learning from audiovisual input, while the more proficient students need some external assurance that exposure to this type of input can support their language progress significantly. As several participants claimed that audiovisual input is not the best way of learning a language and that viewing is not enough to learn from the TV shows, it is important to raise language learners’ awareness (Montero Perez, Reference Montero Perez2022) about their learning outcomes. Language instructors should explain how various viewing modes affect learning of different language features and how viewing original version media is important not only for entertainment purposes but also as a meaningful language activity. An important area of inquiry for future research would be analysing learners’ viewing strategies, as suggested in Kusyk and Sockett (Reference Kusyk and Sockett2012). It would be intriguing to see what viewing activities (e.g. replaying the scenes, noting down unknown vocabulary, watching with L1 subtitles first and then with L2 captions) lead to greater gains. The results of such analysis could shed some light on the effectiveness of viewing strategies and on how learners can engage with audiovisual input effectively.

Finally, we confirmed that viewing habits are not stable, and that they can change even over a brief period of time, especially when there is additional exposure to L2 input through a classroom intervention. The results suggest that regular exposure to L2 audiovisual input can boost language confidence to make elementary-level students switch from dubbed media to original version with L1 subtitles, and higher proficiency language users to watch more without any textual support. This contradicts the popular opinion that students may become over-reliant on captions, and would not be able to switch to an uncaptioned mode. This study provides evidence that viewing with L2 captions may constitute a transitional stage in becoming a confident L2 viewer.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material referred to in this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S0958344024000065

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by grant PID2019-110594GB-I00 from the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation and grant 2020FI_B2 00179 from the Catalan Agency for Management of University and Research Grants (AGAUR).

Ethical statement and competing interests

The study was approved by the Bioethics Commission of the University of Barcelona. The participants provided informed consent to use their data for research purposes. The authors declare no competing interests.

About the authors

Anastasia Pattemore is a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Groningen. She obtained her PhD at the University of Barcelona. Her research interests include second language acquisition, audiovisual input, and individual differences. Specifically, she explores how exposure to captioned, uncaptioned, and plurilingual original version audiovisual input affects learning of L2 constructions both inside and outside the classroom.

Maria-del-Mar Suárez is an associate professor and researcher at the University of Barcelona. Her research interests include individual differences, focusing on language aptitude, multimodality, and digital communicative competence. More recently she has investigated the effects of genres on second language learning as well as the role of formative assessment.

Carmen Muñoz is a full professor at the University of Barcelona. Her research interests include the effects of age and input, young learners in instructed settings, individual differences, and L2 learning through audiovisual input. She is the coordinator of the SUBTiLL Project, on the learning potential of audiovisual input and the effects of captions/subtitles.

Author ORCIDs

Anastasia Pattemore, https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2038-8017

Maria-del-Mar Suárez, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1741-7596

Carmen Muñoz, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7001-4155